[mashshare]

As a high school coach, I’m often asked questions about strength training. This includes the question: “Have I evolved beyond the deadlifting protocol that Barry Ross outlined in his book, Underground Secrets to Faster Running?” The answer is “No.” I’m still using his program because it’s a time-saving and efficient way to get my population of athletes stronger.

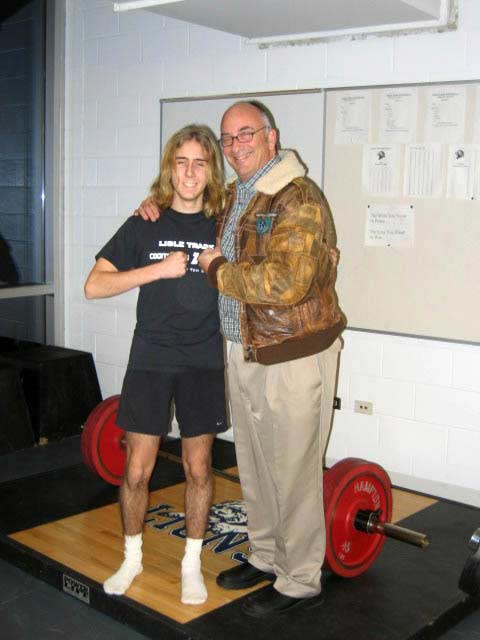

Another question I’m asked is: “Can I really say that a steady diet of deadlifting is making my athletes faster?” My answer to this is, “Yes,” and I have evidence from the “Barry Project” that I conducted back in 2005, and then detailed in a series of posts over at Mel Siff’s Supertraining group on Yahoo. Ross actually flew out from the West Coast to meet with the “test subject,” observe his training, and assess his progress.

A Decade-Old Training Protocol

Before the program started, my hypothesis was that a two-month program of a very specific strength protocol (the one outlined in Ross’s book), would not impact the ability of a high school athlete to achieve significant gains in speed over essentially the same amount of time.

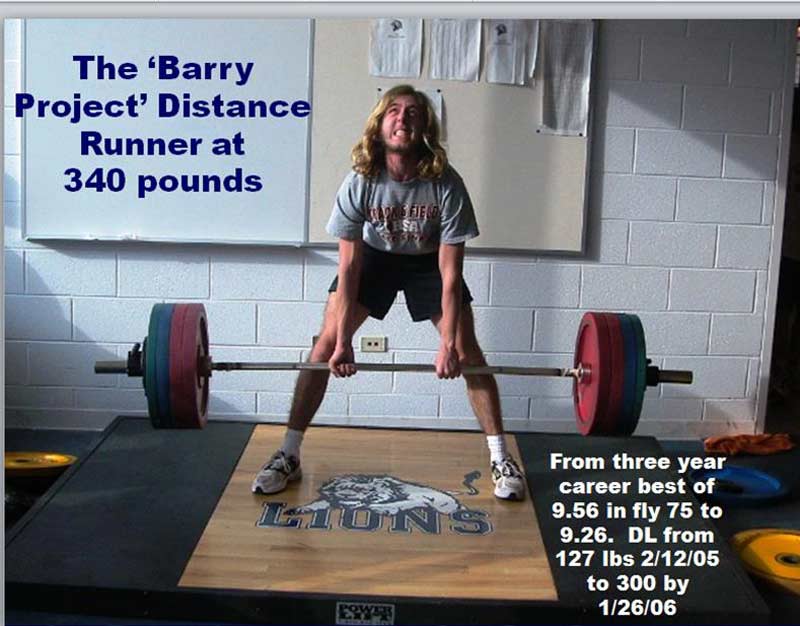

The project had only one test subject—a respectable senior distance runner (10:03 in the 3200) who had no background in any strength training, and had shown no improvement in short speed tests (fly 30’s up to fly 75’s) in the previous three years.

The program began on December 12, 2005. In the first trial, even after preparatory instruction on the mechanics of the lift, the athlete struggled to pull his own body weight (127 pounds), rolled forward on the balls of his feet, and generally revealed what not to do in the deadlift. Seeing this, Ross acknowledged that I had not given him an “easy” subject for this experiment.

However, the athlete progressed quite dramatically. By January 26, 2006, he was deadlifting four sets of three reps at 280 pounds.

His perception of effort was “good” for each lift. He followed each deadlift set with plyos—falling from a 20-inch box and jumping over two 8-inch boxes. He did five repeats of these jumps, and then took a full five-minute recovery until his next set of deadlifts.

Our test athlete also did his push-ups and core exercises as per Ross’s protocol. We then went to the track and set up to run our fly 75’s. We generally don’t do these runs until we are outdoors in late March. However, we caught a 50-degree day, and the test subject was anxious to see what he could run, especially since his efforts in his plyos (surprisingly low contact times) indicated that he might be able to deliver on some of the strength gains he had achieved in the previous six weeks.

Before this, his best fly 75 was 9.56, which he ran in April of his junior year. For his fly 75’s on the day of the testing, he accelerated for 20 meters before the beginning of the timing zone. His first run was 9.26; an improvement from 7.8 m/s to 8.1 m/s. We timed all efforts through infrared beams, and the wind was +2.6 m/s.

He ran a second trial, and his time was 9.46 ( after a five-minute recovery). He was less aggressive in his acceleration to the first beam, and he felt that he would have been even faster if he’d approached the fly-in zone more aggressively. I confirmed his self-analysis, since I filmed a fixed 15-meter segment during each trial (10 meters prior to the second beam).

Video 1: Slow motion video of Steve that shows his stride length.

What is most interesting is that he hadn’t put in any mileage since mid-November (the end of cross country). He typically began training with the distance runners in late February, and his best race performances over 1600 and 3200 meters usually occurred in May.

His top five marks in the 3200 in his sophomore and junior years were: 10:03.16 (5/20/05), 10:07.01 (5/13/04), 10:08.17 (5/07/05), 10:09.00 (4/30/04), and 10:09.62 (05/15/05).

As a sophomore, he recorded his best fly 75 of 9.57 in March 2004. The speed change from his sophomore to his junior year showed no substantial improvement in time (9.57 to 9.56), and off-season mileage and in-season training were exactly the same. Incidentally, the fastest fly 75 in our program over the past two years has been an 8.53, and that was recorded by our top sprinter.

A performance jump this early is quite substantial. I would have normally waited at least another four or five weeks before attempting a speed trial, but he felt very good. He was also anxious to see if this strength protocol alone could have an impact on his short speed even after just five weeks of training, with no base conditioning or sprint work.

His confidence was based upon how well he was executing his plyos. Historically, my best single-leg bounders have been my fastest sprinters, and his elastic response was quite impressive for someone who seldom races below 1600 meters.

He was very pleased, and felt that this minimal investment in time (the entire strength workout takes less than 45 minutes per session, and most of that is in recovery) had a huge upside.

How strong did he get during the protocol? He topped out at an amazing 340. He hit that in the last week of March, before we moved outside.

Despite a pulmonary infection during the outdoor track season, he ran 2:08.87 in the 800 and earned a spot on our state qualifying 4×800 relay. His previous season’s best was 2:18.75.

So, can I draw the conclusion that this approach to strength gain is the best way to help athletes achieve faster speeds?

No. Many factors could have come into play for this impressive success story. Maybe it had something to do with giving our test subject a variation in training from logging all the heavy winter mileage he had done in his previous two years. Maybe it was not having any strength training “bias” from some other strength gain protocol (which I thought was important for this test). Maybe it was the Hawthorne Effect—knowing that he was being filmed and closely observed throughout each day of training. Even the wind that test day might have influenced his performance.

Since that first experiment, I have used Ross’s program with all of my cross country and track athletes. As much as I like the gains that athletes have made over the years in terms of the weight they pulled from the beginning to the end of each season, as with the “Barry Project” itself, so many other variables could have accounted for the speed gains they experienced.

Though I’ve been satisfied that I may be doing something positive for all athletes in the program, I need to answer one overarching question: How does the amount of force produced via heavy strength training relate to the amount of force produced during high speed running?

Disputing the ‘Holy Grail’ of Sprinting

This was the question that Dr. Mike Young, Carl Valle, and Vern Gambetta brought up years ago, and they were right to pose it. Each of them noted that many runners who can pull a lot of weight are not very fast, and many top sprinters are very fast without ever touching a weight

Frans Bosch, whose contemporary insights on strength training have generated considerable interest in the coaching community, said something very similar:

“The strongest athletes are by no means always the fastest sprinters, and evaluation of training always shows that, in somewhat technically complex sports, increased force production does not automatically lead to improved performance.”

There is no disputing what any of them are suggesting. The issue that coaches must acknowledge is something that Bosch often points out: Peak force production in sprinting is larger than what athletes can achieve through maximal voluntary contractions via strength training.

So, how do I respond to the next point that Bosch brings up in his recent book, Strength Training and Coordination: An Integrated Approach?

“If the maximal force that can be produced during strength training is less than what is encountered during high speed running, then strength straining provided no purpose when it comes to overloading.”

If this is the case, how do I explain the impressive gains in speed from my senior distance runner when following the program that Ross carefully outlined?

Bosch seems to have an answer for this.

“Highly trained endurance athletes reach a ceiling in their oxygen uptake. Great mileage will not improve it. However, athletes who wish to increase their V02 max still further can consider maximal strength training as a means of doing so, for improved recruitment will bring more muscles into play.”

When asked about strength work and its relation to the program outlined in his presentation on Critical Velocity Training for distance runners, Tom “Tinman” Schwartz said the following “It’s less important the faster you are.”

I really like that insight because it relates to something Bosch acknowledged in his book: “In beginners, strength training does have a positive impact on some aspects of rate of force development.”

Maybe this has something to do with the simple fact that younger, less-experienced athletes can make big gains through strength training. The more advanced they are in terms of training age and development, the more they need the kind of variation in training that Bosch advocates.

After hearing Bosch speak on two different occasions, and listening to his insights on conventional strength training as a “dead end street,” I have come to understand why he believes that, “overload has to mean more than just ‘more and heavier.’”

Avoid trying to find one set of exercises that contains the secret to running success. Share on XPerhaps he is right. Coaches might be wise to avoid trying to find that one set of exercises that contains the secret to success. As he notes, “There are no Holy Grails in training.” Ironically, Underground Secrets was the title of Ross’s book and, in an article for Dragon Door, Ross refers to the balance between strength gain and changes in body weight as the “Holy Grail of sprinting.”

Current Views on Strength Training

What I have done in recent years is incorporate some exercises that Bosch believes are “particularly good for standardizing and proving this fundamental cooperation between hamstrings and back muscles.”

I now do some single leg deadlifts, which I call SLEDS, and some bench step-ups. I like his analysis of the hang clean, because it does engage the hamstrings isometrically and, unlike a high pull, has what he refers to as an “outcome and intention.” These do provide training variation, which he believes is the “key to efficient coaching.”

Bosch’s book has certainly generated some interest from a training community still somewhat skeptical about such a radical departure from the conventional views on strength training. As Peter Ward noted, “If we have general resistance training for sport on one end of the spectrum… and we have highly specific exercises in the gym that are supposed to get the largest amount of transfer to sports skill on the other end of the spectrum, I would have to say that Bosch is all the way on the highly specific end of the spectrum. I tend to be a more middle-of-the-road type of guy.”

Others offer support for not abandoning these conventional approaches. Jay Dicharry notes that peak forces in running are a product of body mass and running speed. “The faster you go,” he says, “the more strength you need to counter these high forces.”

Steve Magness makes a similar case: “Since we know that force requirement is what determines muscle recruitment, it only makes sense that heavy lifting or high force activities will maximize fiber recruitment.”

Carl Valle commented on one of his blogs that Bosch’s exercises, “seem to only add more complexity to exercises that need less complexity.” But Carl does suggest that coaches buy Bosch’s book and read it for themselves. Challenging his concepts first requires knowing what those concepts are.

Vern Gambetta, who has carefully studied the material, takes a favorable view of Bosch’s insights, and appreciates how they have stimulated his own thought process on the relationship between strength and performance. He noted in his blog that, “My frustration starting with my time as an athlete and extending deep into my coaching career was [not seeing] a commensurate return in performance from the time I invested in strength training. In many respects this is an endless search, but thinking of strength training as coordination training with appropriate resistance is a giant step forward. If nothing else, it will make us more efficient in utilization of time, along with a greater chance of transfer. We need to challenge ourselves in the area of strength training, to break away from conventional wisdom, and seek out new possibilities for improvement. This approach has challenged me.”

So, what conclusion might we draw from the various perspectives that highly respected coaches and trainers have taken on this issue? Perhaps it is to keep an open mind, and experiment for ourselves. As the legendary coach, Joe Vigil, noted in his recent presentation at the Midwest Distance Running Summit, “There are many roads that lead to Rome.”

In terms of how we train our athletes, if we choose the road less traveled, perhaps it will make all the difference in the world.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

- Bosch, Frans. Strength Training and Coordination: An Integrative Approach. Rotterdam: 2010 Publishers, 2015.

- Dicharry, Jay. Anatomy for Runners: Unlocking Your Athletic Potential for Health, Speed, and Injury Prevention. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2012.

- Jakalski, Ken. “Progress of Distance Runner,” on Mel Siff’s Supertraining Yahoo Group. January 27, 2006.

- Magness, Steve. The Science of Running: How to Find Your Limit and Train to Maximize Your Performance. San Rafael: Origin Press, 2014.

- Ross, Barry. Underground Secrets to Faster Running: Breakthrough Training for Breakaway Running. Raleigh: Lulu Press, 2005.

- Schwartz , Tom. “Critical Velocity.” Lecture presented at The Running Summit Midwest 2016, Benedictine University, Lisle, Illinois, June 25-26, 2016.

- Vigil, Joe. “Effective Tapering.” Lecture presented at The Running Summit Midwest 2016, Benedictine University, Lisle, Illinois, June 25-26, 2016.