It was that time of the year again. Summer training camp was here for the upcoming football season, with two practices a day under the blistering-hot Pennsylvania sun. You can still hear the whistle screech and the coaches yell on the line. We headed toward the end line, and the next 20 minutes or so were filled with repeat 100-yard gassers. “We gotta get fast!” “Speed is king!” “Fourth-quarter legs are what we’re after!” Soon 100% became 90%, then 80%, 70%, 60%…until we got to a point where it was all we could do to just survive the next rep.

I’m sure if you’ve played any sport, you’ve likely had a similar experience when it came to coaches and their philosophies about training. But are chronically high-intensity efforts the way to train the power-speed athlete?

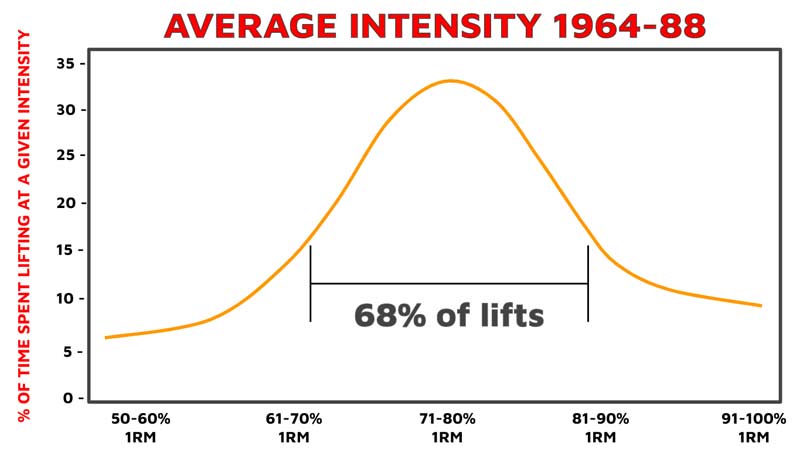

The nervous system can only handle so much, and this system is the lifeblood of athletes. Why compromise it for the sake of crushing yourself in training as a badge of honor? Share on XWhile high-intensity training is not necessarily a bad thing, chronically elevated intensities can be quite detrimental to performance and health—especially when coupled with the stressors of sport and life. The nervous system can only handle so much, and this system is the lifeblood of athletes. Why compromise it for the sake of crushing yourself in training as a badge of honor? Some of the most successful lifters in history rarely, if ever, missed a training rep. They used loads that they had to respect, but they also knew they could technically “wax” during sets.

The prevailing thought when it came to training athletes was to increase their capacity to handle and push through fatigue. Pushing back against that status quo was sport scientist and coach Yuri Verkhoshansky, who is credited with developing “anti-glycolytic” training (AGT) in the late 1980s. Instead of training the athlete to tolerate increasing concentrations of metabolic byproducts, why not instead focus on training the athlete to produce less of it?

This style of training can be used in a variety of ways. It is a favorable method for the speed-power athlete that finds themself needing to reproduce high-level outputs over an entire competition or contest. Let’s take a deeper look at AGT and discuss what it is, how to do it, and why it works for athletes.

What Is AGT?

The basic premise of AGT is to train athletes away from producing excessive amounts of lactate and other unfavorable byproducts. AGT doesn’t mean you can’t train athletes to produce these types of things—you can do it, but you must give sufficient recoveries to counter negative effects.

On the opposite end of AGT, you have the early CrossFit style of training: high-intensity exercises done for moderate durations with minimal rest periods. These acid baths might not harm you right away, but in the long term they can have side effects such as:

- Low energy.

- Elevated levels of “walking around” stress/tone.

- Hormone profiles are out of whack.

- Accumulation of free radicals that lead to oxidative stress and damage to cells.

- Unfavorable adaptations to the heart structures.

AGT, in the simplest form, is using brief, high-intensity efforts with structured rest periods to fully recover from previous work to complete future work in the same manner. If intensities and outputs are maintained over increasing levels of work, you get better. In sports where repeatability is key, AGT seems pretty good. There is an element of specificity that I need to appreciate when it comes to repeatability, but for general power-speed, I like AGT for athletic populations.

Anti-glycolytic training, in the simplest form, is using brief, high-intensity efforts with structured rest periods to fully recover from previous work to complete future work in the same manner. Share on XI’ve used AGT-inspired training with most of my athletes. I implemented an autoregulatory system with my basketball athletes to manage fatigue and create a training bandwidth that emphasizes power-speed. I measure certain sprints, jumps, and key lifts, then prescribe a drop-off range: typically, 5–10% of their best. Once they pass that threshold, we cut training that movement and move on. It has also created a competitive nature during sessions, where my athletes are more engaged and are having fun.

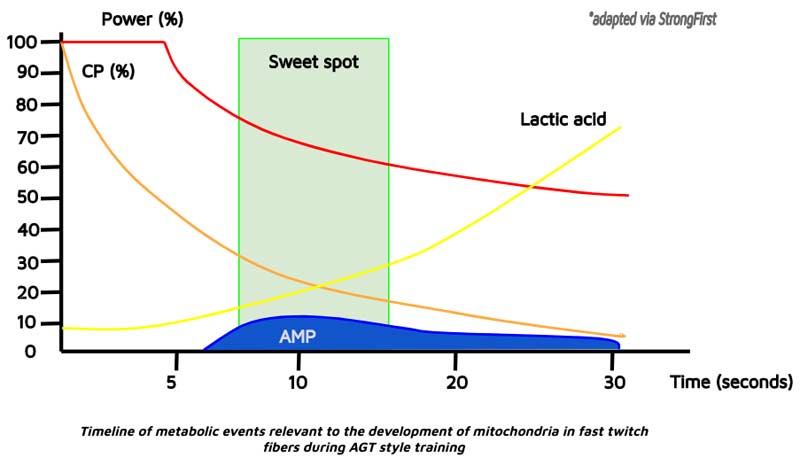

AGT takes advantage of the short-term energy system, better known as the ATP-PC system. Depending on the athlete, work sets can be anywhere from 5–20 seconds of high-intensity work. Rest periods should be enough to recover from each set. You may have to compromise the rest a bit to fit a specific time frame, if needed.

An example would be a seven-second all-out sprint effort. It can take upward of 10 minutes for the body to recover, but most coaches don’t have that time during sessions. A good compromise would be in the 2.5- to 3-minute range. It is enough time to replenish for the next sprint and also make sure that you get in enough sprint volume to produce the adaptation. AGT can be used in the weight room and on the field.

The target quality when using AGT is power training, which is dynamic in nature. To stimulate fast twitch muscle fibers, you can either use force or velocity means. Loads between 30% and 70% can be used for power training. Dynamic lifts such as squats, pulls, Olympic lifts, medicine ball throws, kettlebell swings, upper body presses, and push-ups are all great tools for power training.

Sprinting and jumping are also forms of power-speed development—the key to power training is low reps with generous rest. This allows for maximal efforts that can be sustained through working sets. To be fast and powerful, you have to train fast and powerful. Fatigue is the enemy.

Why Does AGT Work?

As an athlete, you need to be sound in many different capacities. Speed, power, strength, and endurance are the major ones. To improve at any of these requires some sort of specificity in order to target the required mechanisms. Power training, however, has been shown to have positive carry-over into all the abovementioned capacities. This makes training for power a popular training means for the team sport athlete.

A few years back, I came across Pavel Tsatsouline, who I knew from his kettlebell stuff and from his laconic speaking. After a deep dive into his books and his writing, it was clear to me that Pavel has a fundamental understanding of all things strength. Pavel has also written extensively about AGT.

Here are some major concepts I took from his work:

- Take longer rest intervals and use active rest: Longer rest periods allow for the body to regenerate ATP stores and clear waste products that interfere with muscular contractions. Active rest helps promote blood flow and aids in the process of restoration (shaking out arms and legs).

- Strength is a skill: As in sprinting, coordination and rate coding are key elements. Grinding lifts throw off that balance. Manageable loads done with pace and great technique will ingrain better movement patterns (greasing the groove).

- Power feeds all other qualities: F=M*A, using lighter loads with higher velocities is another way to stimulate fast twitch fibers. Even Westside uses their dynamic effort day to increase the work capacities of their lifters outside of max effort work.

- Acid is the enemy of both tension and relaxation: Once you start getting into the burn, you are no longer fast and powerful. Charlie Francis said it best, “If you have a Ferrari, you don’t plow fields with it.”

AGT aims to develop power, stimulating the nervous system and the preferred fast twitch fibers. If you look at elite-level sprinters, many have fairly muscular physiques. This is a byproduct of running fast, jumping, and other dynamic movements in training. That type of training makes for a solid overall athlete, especially in sports that require said athlete to be competent in a wide variety of abilities and qualities.

Training in this manner also keeps acid at bay within the body for prolonged periods. When muscles perform work, they produce byproducts that impair their contractile abilities and coordination after a certain time point. This cuts power and speed noticeably. If athletes train this way for too long, they begin to develop what some call a “dynamic stereotype.” James “The Thinker” Smith (@thethinkersmith on Twitter) describes this phenomenon in his book Applied Sprint Training as:

“From a neuromuscular training aspect, the repetitive exposure to the same/unchanging CNS intensive stimulus presents the possibility of a halt in the adaptation process.”

In essence, you are practicing slow and tired to be slow and tired. The goal of training is to stimulate, not annihilate. Some acidosis in training is fine, but when the threshold is passed, that is where performance and health take the hit.

In sports that may require glycolytic contribution, consider adding a training block to introduce the athlete to it—you don’t want them to experience this state for the first time in competition. Share on XFor the power-speed athlete, a majority of training is away from glycolytic mechanisms. In sports that may require glycolytic contribution, there is no harm in adding a training block to introduce the athlete to it—you’d hate for them to experience this state for the first time in competition.

Mitochondria

One area of focus for AGT is the mitochondria within muscle fibers. Mitochondria are commonly known as the “powerhouse of cells.” They help to generate energy for muscles to contract and produce movement, and mitochondria also work to buffer out unfavorable byproducts that begin to accumulate during exertion.

Without bigger and better mitochondria, our room for error is much slimmer than it would be if our mitochondria were trained to be healthier. Mitochondria are present in both fast and slow twitch muscle fibers. Slow twitch fibers are pre-equipped with a fair number of mitochondria to aid in aerobic functions. Fast twitch fibers, however, have fewer concentrations, which leads these fibers to fatigue more quickly.

There are ways we can train mitochondrial capacities in both sets of fibers. The concept of AGT shows us some ways we can do it in our programs. This post by strength and conditioning researcher Chris Beardsley gives a more detailed view of the role of mitochondria in both fast and slow twitch fibers.

How to Program AGT?

In my judgment, both the aerobic and alactic systems should be trained in athletes. The commonality of approach to training both systems would be to reach the brink of acidosis in the muscle without overflooding and experience the perennial dip in performance. This can be accumulated through training to reach the desired fitness levels needed for the athlete’s sport.

In fast twitch fibers, AGT has been shown to somewhat increase the mitochondrial quantity (size and number), although it is not optimized for it. The goal is to provide an aerobic environment within fast fibers that triggers the generation and effectiveness of mitochondria. Upgraded mitochondria are better able to handle the increasing influx of acid as it makes its way into cells. Taking the underlying message of AGT, there are a few routes that coaches can implement to realize these adaptations.

- The duration of high-intensity efforts should be around the 5- to 15-second mark depending on athlete qualification.

- Rest periods should optimize for full recoveries while respecting time constraints.

- 3–5 minutes is a good starting point.

- Don’t exceed 10 sets of a movement or 100 reps (that is the ceiling).

- Manipulate set/rep schemes into series to allow for repeatability of outputs.

- Pavel and others have found these to be the best:

- Five reps per set, one set every 30 seconds, four sets per series, keep total volume under 100 reps.

- Ten reps per set, one set every 60 seconds, two sets per series, keep total volume under 100 reps.

- Choose simple exercises with light to moderate loads to emphasize power.

- Pavel and others have found these to be the best:

Programming this for weight room exercises will be different than for field work. When sprinting, we must consider what high-speed running can do to the unprepared athlete. Like anything, we have to build up to it.

Structuring speed sessions with reps, sets, and series can allow for better runs without the accumulation of fatigue. This is a key factor for sports that involve repeated bouts of high-intensity efforts. Timing sprints for a certain drop-off threshold is a good way to establish a floor and ceiling with your athletes.

The same concept applies for jumping/plyometrics or velocity-based training. If you can get some baseline data, then you have a cut-off point to use so that power isn’t lost because athletes are gassing out. Your ending volumes for both sprints and jumps will match your needs analysis. Step progress to match the demands of sport.

When training the mitochondria in the slow twitch fibers, the best way is through steady-state aerobic exercise below the lactate threshold. I am not sure if science has looked at tempo runs and zone 2 cardio and what goes on at the cellular level, but empirically, both seem to work.

One protocol that I have seen successfully work is Peter Attia’s zone 2 training. Peter trains on an exercise bike at the highest watts per kilo while maintaining a lactate level below 2.0 mmol. His weekly sessions are either 4×45 minutes or 3×60 minutes. A rule of thumb when using tempo runs is to go under 60–65% of best time and maintain a pace where you can pass the talk test.

Training slow twitch fibers through strength training has also been successfully done by coaches. Professor Victor Selouyanov developed a slow twitch hypertrophy program that you can find if you do some digging: the basic premise is light, very slow movements through a limited range of motion. Selouyanov recommends very long rest periods between these types of sets: upward of 5–10 minutes of active and passive rest to fully recover for the next set. If you are interested in this type of training, I recommend looking deeper into it. (Please see the bottom of this article for some resources to start with.)

Another major takeaway when implementing AGT principles is using rest periods to your advantage. Active rest is a good option when paired with power-speed training. Share on XAnother major takeaway when implementing AGT principles is using rest periods to your advantage. Active rest is a good option when paired with power-speed training. Fast and loose movements, like shaking the arms/legs, can help the process of clearing fatigue. Passive rest can be used, but recovery periods might take a bit longer. If you have the time to optimize rest intervals…use it.

Biological Power

I’ve come across a few variations of this concept of what Verkhoshansky would describe as biological power.Paraphrasing from the great professor, the 50,000-foot view of this is:

“The mechanical power of a biological system is supported by physiology. This is the power of the living organism. To increase mechanical power is to increase the mechanism of energy through the development of the energy systems.”

The big idea that I took away from my own research is that the overall health of the organism and the capacity of each biological system has a direct impact on what they can “give.” If an individual has not built up the reservoir to pull from, they are hindered in their resource allocation to training/competition.

A short and sweet quote I think of is that a rising tide raises all ships. Doug McGuff, a full-time practicing emergency physician and owner of the facility Ultimate Exercise, calls this concept “physiologic headroom”: the difference between the most you can do and the least you can do. This concept speaks to the importance of common sense training along with proper sleep, nutrition, hydration, and lifestyle management in order to set the stage and allow for more to be directed toward training. Don’t start from a deficit because we couldn’t get the simple stuff right in our time outside of training.

Why is this important in AGT? The training methodologies that we use should have the interdependence of the human body in mind. There are downstream effects to every decision we make and stressors we incur. If we can promote health in athletes along with boosting performance, we have a win-win.

The concept of AGT is fluid in strength and conditioning: depending on what you are trying to train, your training variables will mirror that of using alactic + aerobic mechanisms. Share on XAnti-glycolytic training (or similar philosophies) is not anything revolutionary. These approaches tend to get lost in the fray due to the flashy and grinding methods popular with social media, but this style of training is effective.

The concept of AGT is fluid in strength and conditioning: depending on what you are trying to train, your training variables will mirror that of using alactic + aerobic mechanisms. There may be no definitive template, but as a coach, you can develop your own sample size through some simple data collection. The education piece upfront is important to get buy-in from athletes. The job of strength coaches is to prepare and support sport-participating athletes, keeping precious resources allocated to the field or court.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Resources

Smith, James. Applied Sprint Training. Vervanté, 2014.

Tsatsouline, Pavel. “How to Build Your Slow Fibers Part III.” StrongFirst, 3/17/21.

Tsatsouline, Pavel. “How to Build Your Slow Fibers, Part I.” StrongFirst, 10/20/17.

Tsatsouline, Pavel. “How to Build Your Slow Fibers, Part II.” StrongFirst, 10/19/18.

Tsatsouline, Pavel. “The Patience of Strength: The Russian Science of Rest Intervals.”

StrongFirst, 10/20/17.

Tsatsouline, Pavel. “The Quick and the Dead vs Strong Endurance™-What Is the Difference?” StrongFirst, 2/7/20.

Verkhoshansky, Y. and Siff, M.C. (2009). Supertraining. Verkhoshansky SSTM.