Jillian Zeller is in her first season as the Sports Performance Coach for San Diego Wave FC. Most recently, she was at University of Southern California as a strength coach for women’s soccer, lacrosse, and beach volleyball (four-time national champs.) Jillian has spent the last 10 years in the collegiate sector working with various sports and institutions.

Freelap USA: You were a part of the USC Women’s Beach Volleyball championship season. What were some of the programming considerations that you made entering the post-season? How much did it differ (or not differ) from your traditional in-season programming to consider the length of the post-season?

Jillian Zeller: They actually just won another championship this year! That shows how special that group was.

There were many factors that contributed to the success of these back-to-back championship seasons. First, the mindset. The goal was to always win it all. Athletes started each practice with mindfulness and intention-setting. They also conducted culture class on a weekly basis. This laid the foundation for tremendous leadership, which was a huge contributing factor in the team’s success.

Drive, accountability, and trust were pillars of this group. The team trained five times a week:

- Monday – Speed session

- Tuesday – Weightlifting

- Wednesday – Conditioning (on sand courts)

- Thursday – Weightlifting

- Friday – Conditioning

Although in the game of beach volleyball there is not much true sprinting, the sport requires repetitive explosive efforts. Research and coaches like Boo Schexnayder would suggest that the development of sprint qualities benefits the development of plyometric qualities. Tendon stiffness, rhythm, force production (high motor recruitment), and maximum output are all qualities you can develop with a speed program to help your vertical and horizontal jumps.

Because the demands of the sport are so elastic, we focused on general and absolute strength in the weight room. If I could increase their force output, they would become an even more robust athlete. Sessions included Olympic lifting variants, upper body pulling, posterior chain, and multiplanar movements.

The demands of beach volleyball are so elastic, we focused on general and absolute strength in the weight room. If I could increase their force output, they would become more robust athletes. Share on XThe demands of the game do allow for a little bit of aerobic capacity work—the conditioning twice a week would serve that purpose, and I always kept it competitive to drive intent. We tried to keep this schedule as late into the season as we could. As the season went on and weekly games increased, our overall volume went down. For example, I would pair a speed session with a dynamic effort lift day. Conditioning sessions could be exchanged with yoga sessions to focus on meditation and mobility.

Ultimately, programming didn’t differ too much from what we did in the off-season. The consistency of training definitely contributed to the team’s success.

Freelap USA: Congratulations on your new position with San Diego Wave FC. Over the course of your career, you worked with USA Women’s Hockey, Boston University, and Wake Forest as well. What are some of the biggest things to consider when transitioning from the collegiate to the professional setting?

Jillian Zeller: The college and pro settings are definitely very different. In the college sector, it is a three-month season, whereas in the professional setting, it’s an eight-month season. Therefore, load management and player sustainability are a primary focus. I am fortunate to work for a club that has very thorough communication between performance staff and technical staff on a daily basis.

From a training perspective, we microdose as much as we can. I am a believer in Mike Boyle’s minimal effective dose. How can we adapt and progress in such a long season? Everything is calculated based on the needs for the day and the weekly load. For instance, warm-up could include a max velocity effort or 90% efforts or tempos.

We also conduct plyometrics and agility 2–3 times a week. We strength train twice a week as well. Because we are in-season now, it is a mix of small progressions where we can and maintenance. Everything that we do as a performance staff is based off daily GPS metrics, wellness questionnaires from Smartabase, and force plate data.

Freelap USA: What are some of the training considerations for the feet and ankles that you prioritize for your athletes based on the different surfaces they compete on—e.g., ice, turf, sand, court, and grass?

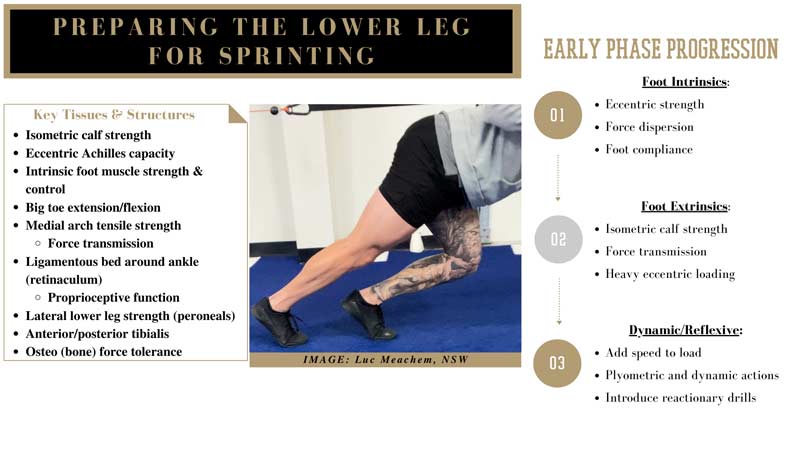

Jillian Zeller: I have worked with athletes on all types of surfaces, and there are definitely things to take into consideration. For most athletes I work with, we start by completing extensive plyometric patterns and isometrics to build tissue tolerance and tendon health. For example, the ALTIS rudimentary series or a floating heel isometric.

A sport like beach volleyball requires a high force output on a surface where force dissipates, so tendon health and force production are paramount. For field sport athletes, I believe multiplanar skipping patterns are low-hanging fruit. These require rhythm and can challenge the ankle in different directions. Ultimately, it comes down to how the athlete absorbs and produces force from the ankle complex more than the surface they compete on.

Freelap USA: You place an emphasis on mental training and mindfulness among your athletes. Why do you believe this is beneficial to athlete development? And how do you incorporate it into your training programs?

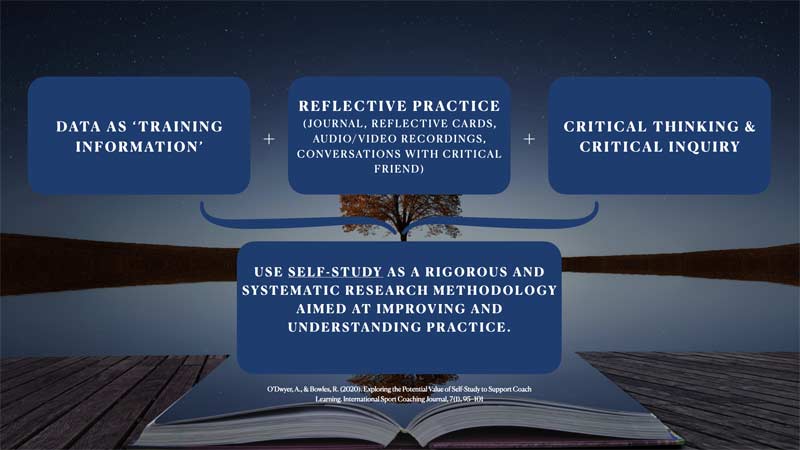

Jillian Zeller: Your body will follow your mind and your heart. Mental training is crucial to physical training at any level. Fortunately, I have always been a part of programs that utilize sport psychology. The ability to reflect and be honest with yourself carries over to how you are as a teammate. I believe mindfulness should be the first skill athletes learn.

Your body will follow your mind and your heart. Mental training is crucial to physical training at any level. I believe mindfulness should be the first skill athletes learn. Share on XStrength and conditioning is a great vehicle for mental skills. If you think something is going to be hard, it will be; if you think it’s going to be easy, it will be. What are ways we can make our mind up and just go for it? If you have tools that help you problem-solve, you are better equipped to face moments of adversity. If you have practiced ways to find a second of stillness during commotion, you are more prepared for big-pressure moments.

As a coach, I can make things physically hard and discuss ways to attack those things individually and collectively. I am a huge fan of competitions and drills that involve communication in chaos and teamwork. It’s situations like these that create trust and discipline.

It also exposes teams to things they are not good at, but it is important to take the time to push and problem-solve together. It can be as simple as redoing a warm-up until it’s perfect or having everyone in cadence during a lift. Make the team communicate (what direction they must turn, what rep they are on, etc.) during a conditioning session. If the team can practice these skills with us (strength coaches), they will be prepared to utilize them during competition.

Freelap USA: As a female strength coach, it can be difficult to establish yourself in this field. What are some of the biggest lessons you’ve learned, and how have they made you into the coach you are today?

Jillian Zeller: Be humble, be relentless, and be curious. I think to establish yourself, it is important to learn, support, and challenge the people around you. All of the above is regardless of gender, so never let being a female get in the way.

I think to establish yourself, it is important to learn, support, and challenge the people around you. All of this is regardless of gender. Share on XBe a coach; be a role model. I am the coach I am today because I’ve had great mentors, I’ve taken big risks, and I put my whole heart into whoever I am coaching. I would tell any female to go outwork and outsmart your competition and let’s continue to support one another.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF