The coaching process is defined as “the purposeful improvement of competition performance, achieved through a planned programme of preparation and competition.”1 At its core, the coaching process is influenced by different sciences such as exercise physiology, anatomy, biomechanics, pedagogy or the science of teaching, psychology, testing and measurements, and statistics, to name a few.2 However, it is truly a blend of science and art where the coach operates a complex, dynamic social activity that is goal-oriented with a focus on bringing about change.3

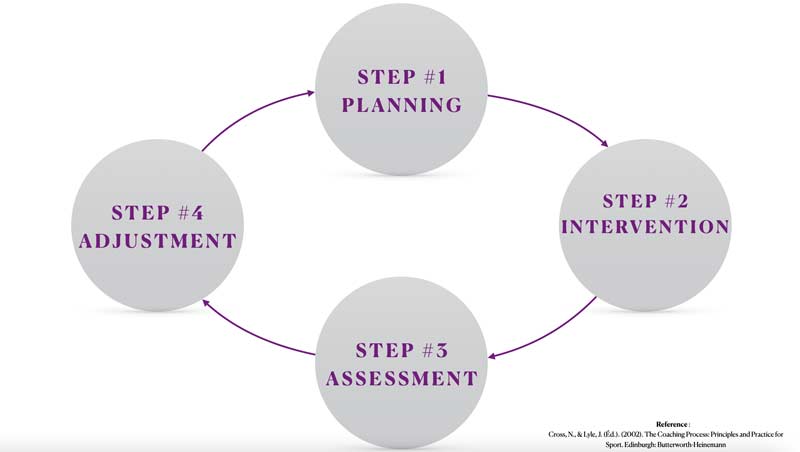

It is truly a blend of science and art where the coach operates a complex, dynamic social activity that is goal-oriented with a focus on bringing about change, says @xrperformance. Share on XAs an orchestrator, or Chef du Projet Performance, the coach coordinates the coaching process within set parameters to instigate, plan, organize, monitor, and respond to evolving circumstances in order to bring about improvement in the individual and collective performance.4 To help with the overall planning of this process, four main steps are usually included:

- Planning

- Intervention

- Assessment

- Adjustment

Planning

As a starting point, the coach uses existing professional knowledge about the physical, technical, tactical, and psychological demands of the sport to plan what needs to be done. Using the analogy of a road map, the coach has a destination in mind and an idea of how to get there but will most certainly need to manage a few uncertainties along the way.

For me, one example to support this analogy of the road map came about in the early 2021–2022 off-season with the men’s volleyball team at Université de Sherbrooke. As a coaching staff, we knew that we were working within a three-year plan, with all players but two having never played indoor volleyball at the university level. We were thus at the beginning of the journey, and our destination was clear; however, information about the upcoming university sports season was lacking at the time because of the pandemic, so long-term planning for games and playoffs was impossible.

To remediate the situation from an S&C perspective, I decided to think short-term and focus only on the summer off-season training. I remember telling one player that there were just too many unknowns to start planning the weeks of training during the competition phase. By limiting myself to the summer months, I was able to sequentially organize the training to take advantage of the phase potentiation associated with block periodization.

For example, the month of May was an introduction phase during which we focused much of our training on technique and used bodyweight movements to develop mobility and work capacity. This first training block was our foundation for the next three training blocks, which had a focus on preparation.

In June, our priority therefore shifted from teaching to training and saw the introduction of DB complexes, spectrum legs, and leg circuits to increase basic strength. During the month of July, it was possible for us to divide the group into two following some force plate testing, with one group focusing on eccentric strength and the other on maximum strength. Finally, August came around, and our focus was on developing muscular power through Olympic weightlifting, plyometrics, and maximal power training.

After these training blocks, it was possible to reevaluate the direction of the training, as new information about the upcoming season was now available. So, instead of planning for the whole season and hoping to peak for the playoffs, we reviewed our plan using a smaller time frame that allowed us to better manage uncertainties associated with COVID-19. After all, “training is a predictive process based on experience and scientific knowledge aimed at rationally, systematically, and sequentially organizing training tasks and the recovery process in order to reach performance goals at specific times.”5

Instead of planning for the whole season, we reviewed our plan using a smaller time frame that allowed us to better manage uncertainties associated with COVID-19, says @xrperformance. Share on XAt this moment, it is beneficial for the coach to perform a thorough analysis of the physiological and physical demands of the sport. Performance in different sports has evolved over the years and access to integrative technology such as GPS or accelerometers allows for a more refined analysis of the demands of a sport in general, and even the positional demands within it.

For example, recent investigations6,7 in ice hockey used a local positioning system (as opposed to GPS technology because of the inability to connect to satellites in an indoor environment) or inertial measurement units8 to quantify and track the movement demands during games, whereas previous research mostly used heart rate to quantify the physiological demands of the game.

This necessity for a thorough needs analysis of the sport brings me back to the 2016 and 2017 seasons with the Canadian Football team at Université de Sherbrooke. We were fortunate at the time to be able to use a set of 10 GPS monitors during practices and games for a research project.9 During one game in 2016, I remember clearly watching some of the metrics being displayed live during a kickoff and thinking: Shoot, we have not trained special team players to sprint over long distances such as those displayed during a kickoff. Indeed, during summer training, most of our sprint distances were below 20-30 meters, while longer running distances were covered during our high-intensity interval training days.

Overall, having access to this information when planning future training can allow the coach to better prepare the athletes from an S&C perspective or replicate game situations that resemble what can happen in competition. In my case, I certainly made the necessary adjustments to better prepare the players to meet the demands of this specific aspect of the game.

Intervention and Assessment

During the training sessions of steps #2-3 of the coaching process, the coach actively teaches, provides instructions and feedback, manages desired behaviors, and asks questions to assess learning. At this point, as an orchestrator, the coach steers rather than controls the coaching process through unobtrusive monitoring and mutually agreed-upon agendas and by providing players with encouragement.

The steering—or monitoring—of the coaching process during a training session or over a longer period allows the coach to collect “decision-making information” from various sources.10 By looking for trends in training and performance, the coach actively seeks to answer the following questions:

- Are we getting positive training adaptations?

- How effective is the training program to meet the demands of the sport or the demands of the game model we want to implement?

- From a behavioral perspective, are we getting the desired behaviors from the players?

By implementing a monitoring process, either via objective measures like heart rate or force plate data or even subjective measures such as wellness questionnaires11, the coach seeks to measure or know the individual response to different stressors (emotional, dietary, social, sleep, academic, sport). This data provides direction and supports the decision-making process. After all, it’s okay to deviate from the preplanned path if the data or information collected by the coach can drive future direction.

After all, it’s okay to deviate from the preplanned path if the data or information collected by the coach can drive future direction, says @xrperformance. Share on XAdjustment

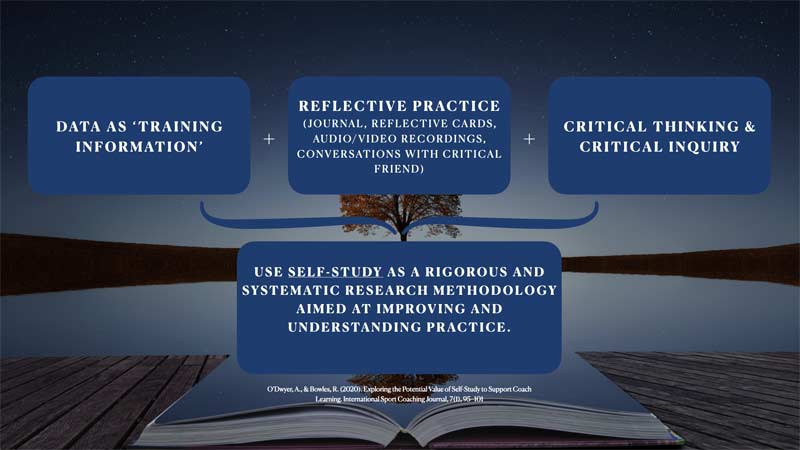

After collecting the “training information” available to them in the previous steps, how can coaches explore and question their decisions and experiences within the context of their own practice in the fourth step of adjustment? When triangulated with reflective tools and critical inquiry and critical thinking, this “training information” can be used by the coach to explore, question, and contextualize their professional practice with the objective to learn and become a more effective coach.12

The picture below shows how data, reflective practice, and being critical of oneself and one’s experiences can be used to support learning:

To give you an idea of this reflective process, during my PhD, Canadian football coaches at the university level were presented every week during the competition season with their players’ session RPE training loads as “training information.”13 This type of subjective monitoring of the training is quite easy to implement and can be adjusted to different sporting contexts.

In terms of reflective practice, coaches were asked to fill out post-training and post-competition reflective cards regularly. The post-training reflective cards required the coaches to briefly describe the training session, evaluate what went well and what went wrong, analyze why the session went the way it did, and provide an action plan for the next session. Meanwhile, the post-competition reflective cards required them to evaluate the team’s performance on a scale of 1-5 and provide some thoughts following the game.

During the weekly meetings, coaches were asked to comment on the results of the game and on the data they were presented with and how that data influenced their own decisions in terms of practice design. At the conclusion of this project, it was interesting to note that having access to the training load data and engaging in an emergent reflective process allowed coaches to contextualize their decisions and, at times, provide different scenarios in reaction to the data that was shared with them.

To encourage this exploration and questioning of their decisions and experiences, it is essential to promote a structure where reflective practice and experiential learning are supported and facilitated. The support of fellow coaches, mentors, critical friends, and even the organization as a whole is necessary to advance learning.

The support of fellow coaches, mentors, critical friends, and even the organization as a whole is necessary to advance learning, says @xrperformance. Share on XThe use of self-study methodology to improve and understand one’s practice thus becomes quite interesting, because we now know that learning is much more than the accumulation of knowledge.14 In fact, it is more about becoming an integrative thinker and changing one’s cognitive structure by creating a vast network between our knowledge, our ideas, and our feelings.15

Furthermore, the knowledge that is gathered by coaches over the years tends to be quite different from the theoretical knowledge one can find in textbooks or in the scientific literature. As suggested by Mills & Gearity16, the knowledge gathered in a socially simple environment such as a laboratory needs to be adapted to the realities of the socially complex environment of a coaching group.

Going Full Circle on Becoming a Better Coach

The coaching process is an iterative practice of collecting and using various sources of “training information” to improve the performance of athletes or teams. This process needs to include some form of reflective practice or introspection from the coach so that they can learn from their experiences to adapt and/or change their behaviors in a coaching environment that is dynamic, complex, and often chaotic.

This is not easy, but improving a coach’s knowledge and coaching qualities does make an impact, not only on their personal and professional development, but also on the athletes they work with.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF