As much as coaches and practitioners like to attribute soreness and tightness to just being a part of the process, it cannot be lost on us that expediting the return to optimal is very much a part of our fundamental duty. There’s no doubt that athletes will get beat up during the season and throughout particular phases of the training cycle. However, considering the optics and fundamental roles of a strength coach, it can be easy to slip into autopilot with restorative modalities. The old adage “the best ability is availability” holds a great deal of truth, and beyond having our athletes physically uninjured, we should also take a sense of pride in having them feel as close to optimal as possible for as many games/practices as they can.

It’s important that coaches understand the spectrum of tightness and break this mold of inherently assuming the solution for tightness is copious stretching, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XConventionally, “tightness” has been associated with “a need to stretch.” But as we’ll discuss in this article, it’s important that coaches understand the spectrum of tightness and break this mold of inherently assuming the solution for tightness is copious stretching. While stretching is often a part of the solution, it is far from the only one. Likewise, the state of the muscles and connective tissue are certainly a part of the restriction but not always the full scope of what is limiting the movement.

An important distinction here before we get into the X’s and O’s regarding tightness: tightness should not inherently be perceived as a bad thing, nor should it be mistaken for “functional” stiffness. There are several instances where stiffness or tightness isn’t only needed but highly beneficial for strength and speed. Some easy examples are the ankles and hamstrings of a sprinter and the lat and triceps of a pitcher. In specialized cases like this, looking to “stretch” their tightness away would destabilize the athlete and likely compromise performance, while potentially amplifying injury risk.1

Another situation is with athletes who’ve had major surgeries or injuries. The additional fibrous tissue (collagen) surrounding the injured site can be needed for stability and structure. I call this protective tension, and if we aggressively seek to “undo” this tension, it can destabilize the athlete while potentially affecting confidence in the area negatively. The main point being, don’t get carried away with overstretching and mobilizing every athlete you see on equal terms—not all athletes need to stretch/mobilize the same.

What Does “Tightness” Even Mean?

“Tightness,” aside from being an all-time favorite buzzword for coaches and practitioners to gripe about, is a term that lacks clarity. While there are obvious technical limitations to the term tightness, the general understanding is that tightness is an indication of stiffness or restriction, usually centralized to one area/muscle group (and, at least in most cases, believed to be chronically shortened muscles that prohibit the full ability to move and thus the sensation of feeling “tight”). While the simplicity of this thought is appealing, the fact is that’s just not the full story.

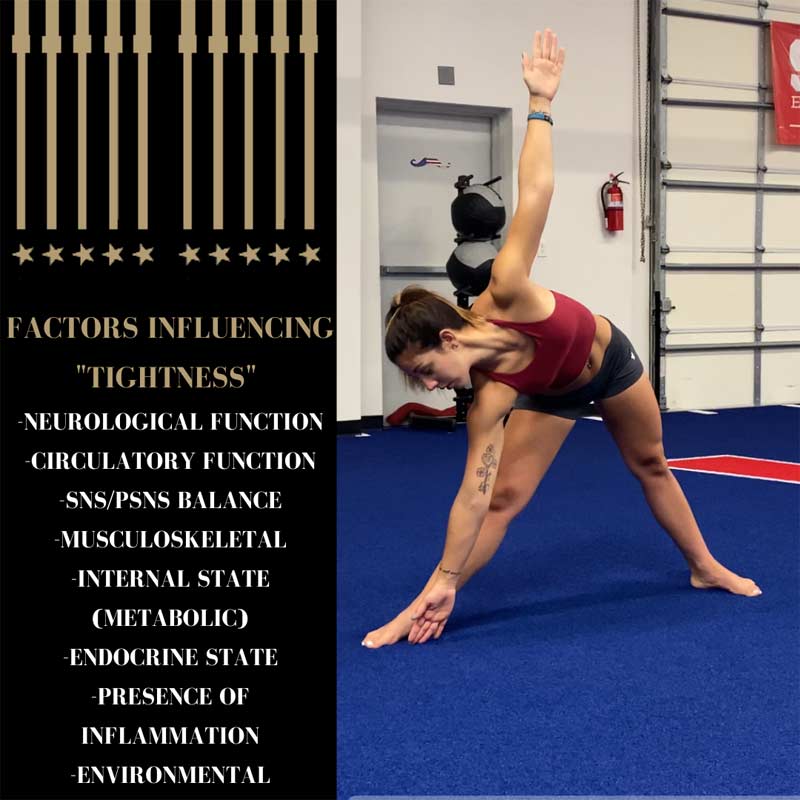

Tightness in and of itself is multivariant and can be the result of many things. This is why it’s critical to objectively evaluate movement with a wide perspective and never assume.

For instance, the presence of inflammation (lymphatic, interstitial, or injury site), a lack of circulation (hypoxic tissue), changes in blood/gut pH, cognitive impairments, and changes in environment (e.g., temperature, barometer), among other factors, can all be consequential for movement ease.1

Misapplications of stretching have been rampant in performance settings, and I believe it begins here with the misconception of using stretching modalities as a means to reduce soreness or tightness.

Another mistake that’s even more common is chronically stretching muscles that feel tight but are in reality just weak, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XStretching athletes who are sore from training or sport—especially vigorously—is rarely a prudent solution, at least not in isolation. They are experiencing more of a biochemical/fluid disruption or stagnation than they are tissues being “shortened.”1 Thus, the best recipe in these cases is to hydrate, sleep well, and promote blood flow to the area. Another mistake that’s even more common is chronically stretching muscles that feel tight but are in reality just weak. Stretching exhaustively when the deficit is strength-based only makes a bad situation worse.

If you’re one of those “I stretch all the time but always feel tight” people, I’m speaking to you here.

Movement Hierarchy

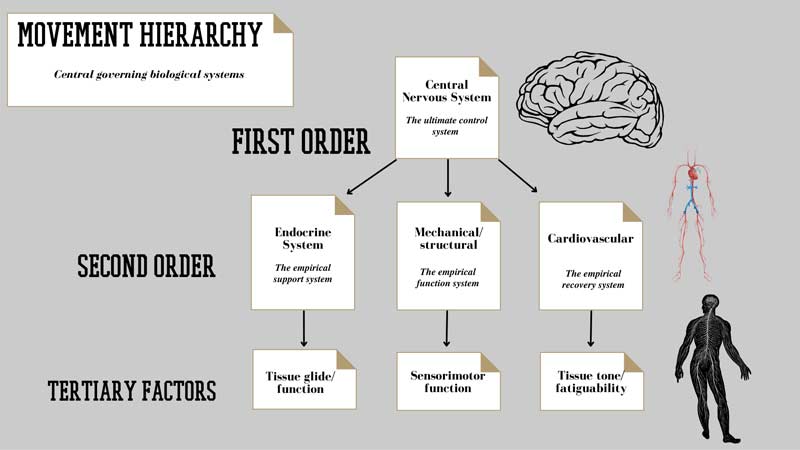

Human movement is remarkably sophisticated. And although we’ve tended to oversimplify our biology for the sake of understanding, we need to be able to recognize and appreciate this complexity. Human biology largely works in a hierarchical manner, in which central (bigger) systems will inevitably govern peripheral (or smaller) ones. As such, no matter if we’re discussing stretching, strength training, speed, or power development, we cannot ignore the principles of hierarchical order.

The first place to start is always with the central governor: the brain and central nervous system (CNS). As Stu McGill has said, “Stretching is just playing with the neurology.” What he means by this, as an example, is if an athlete is in true sympathetic overdrive (i.e., overtraining) resulting in a constant state of tightness, we can do all the stretching and mobility work in the world, but until the sympathetic (SNS) and parasympathetic (PSNS) nervous system balance is addressed, the athlete will still feel sore/tight, leaving our efforts in vain. Another common example of this is with endocrine and hormonal functions, in which the internal state (including pH balance) will precede any soft tissue, muscular, or joint capsule restriction.2

Working down the hierarchy, we have a few additional considerations as well. The distribution of collagen fibers (fascial densification), muscle fiber type ratio, tendon length and insertion, and localized circulation are a handful of additional factors that may have a significant influence on the sensation of stretching and how we approach treating it.3 As with anything else, these systems, ratios, and functions are different across different populations/individuals; likewise, the approach must be modified to fit the specific demands.

Classifying Movement Restrictions

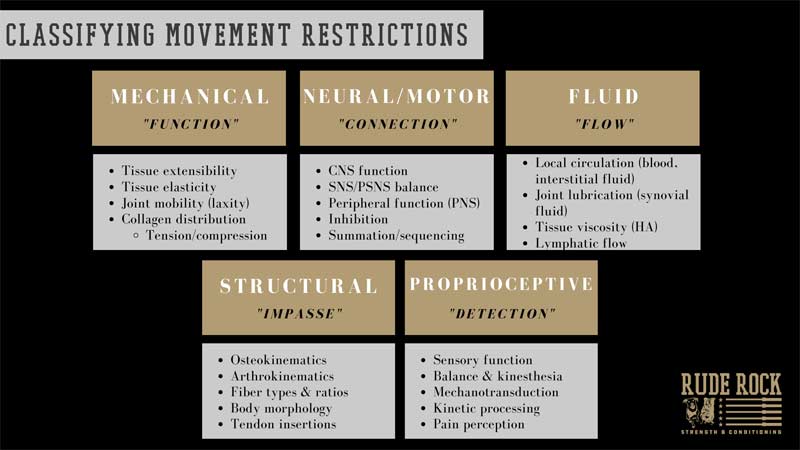

I classify movement restrictions in one of five ways:

- Mechanical

- Neural/Motor

- Fluid

- Structural

- Proprioceptive

Utilizing the criteria and points outlined above, we can essentially stratify movement restrictions to help set the template for how we approach movement limitations. Not only will the exercise selections and modalities be different based on restriction type, but there are programming and recovery strategy considerations that may differ as well.

Not only will the exercise selections & modalities be different based on restriction type, but there are programming & recovery strategy considerations that may differ as well, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XAn example here is that someone with poor aerobic function and another with neuromuscular deficits should not have the same protocol, whether we’re addressing tightness or anything else. Where a mechanical restriction may suggest more stretching/soft tissue work, someone who is lacking in aerobic function may get more out of additional Normatec time or simply walking outside rather than additional stretching.

These classifications can be as refined and rigid or as loosely guided as you’d like them to be. The important point here is that, if nothing else, you can understand and identify the multitude of factors that can create tightness, limitations, or soreness. For me, the primary variables that this stratification chart influences are the training parameters and time allocated for restorative/recovery modalities.

Broadly speaking, mechanical and (some) neurological deficits tend to respond best to good old-fashioned strength training and some sidecar designated mobility/flexibility work. Meanwhile, fluid and proprioceptive deficits tend to be more nuanced and are more likely to require specialized treatments and modalities.

Solving Movement Restrictions

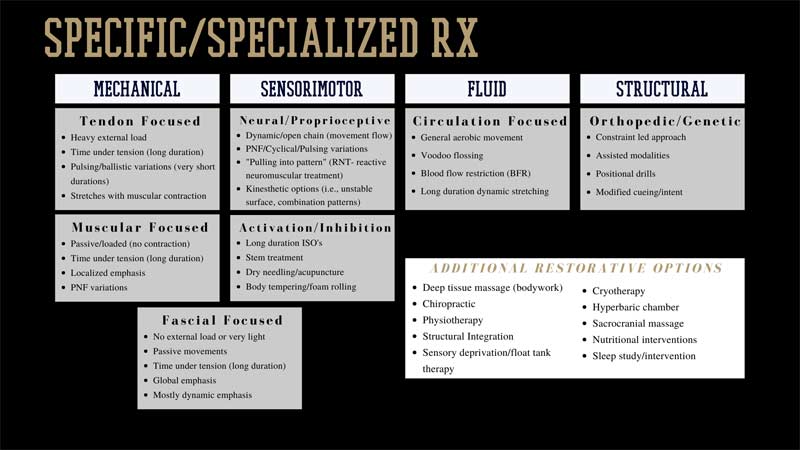

This is the point where we need to really go beyond the default stretching routines we’ve recycled for the last few years and look to branch out. No different than the strength toolbox, with restorative modalities and programming, it doesn’t hurt to have a few different tools you can pull from when needed. That being said, having a bigger toolbox doesn’t mean we always need to throw everything we have at every athlete we see. There is a time to be general, or as I call it, using your machete; but when a specific approach is required, we need to be able to pull our scalpel out.

There are a couple areas that I want to focus on from the graphic above: the fluid and proprioceptive restrictions. These two, in my opinion, highlight the multivariant nature of movement restrictions. With the concept of tightness, these two are often major contributing variables, as the fluid stagnation is typically confused for muscular tightness due to sensation. When we have fluid stagnation, no amount of stretching or mobility alone will solve the issue; we simply need to push fluid and keep the body moving to resolve our tightness issue.

We can stretch for hours on end with no resolution if there is a proprioceptive imbalance or impairment, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XLikewise, the proprioceptive inhibition is another essential component to resolving tightness. Recall that the proprioceptive bodies in fascia, muscle, and other connective tissues are literally the sensory and signaling interface for our body.2 Once again, we can stretch for hours on end with no resolution if there is a proprioceptive imbalance or impairment. Sometimes this requires advanced treatment, but in most cases, we can address this through perturbative or oscillatory work, band-assisted stretching (below), or even things as simple as breathwork to reset our proprioceptive input.4

Video 1. Band-assisted stretching.

General cases (i.e., general/acute soreness/tightness/fatigue) normally don’t require much in particular. I think of this as having a wide spectrum with a shallow focus—use a wide variety of things without hammering any. Including a good rotation of dynamic stretching, light aerobic work, some foam rolling/body tempering, and submax strength training during your warm-up/movement prep periods will check a lot of common boxes and have tangible value across most athletic populations.

For the specific cases (e.g., returning from a rotator cuff tear, plantar fasciitis, mechanical overload syndrome), this is where the general “x, y, z” alone won’t cut it. And even to a lesser extent, such as an athlete who has a clear connective tissue deficit (passive ROM), or one who struggles proprioceptively, we need to be refined in our approach.

For designated and specific recovery strategies, particularly during in-season periods, I would say a good round number to shoot for is 60 minutes per week. This can come in the form of one or two 30- to 45-minute designated training sessions or a daily practice of 10–15 minutes across most days. (Note: This type of work can always be instructed for the athletes to perform on their own, pre- or post-training.) It all depends on how constrained you are in your setting.

In college settings, it may be more practical to teach athletes early on as much as you can and depend on them to be autonomous. In the high school setting, on the other hand, restorative days may need to be fully supervised to ensure effectiveness.

Stretching Isn’t a Cure-All

Tightness is multivariant in nature and not always a negative. As with everything, coaches need to be able to understand the context of the situation and demands of the sport. If we apply copious amounts of stretching and see no resolution in perceived tightness, we’re misidentifying the culprit and/or doing something wrong.

If we apply copious amounts of stretching and see no resolution in perceived tightness, we’re misidentifying the culprit and/or doing something wrong, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XTake a step back, analyze some of the compounding or contributing factors, and see where there’s a disconnect. Prioritizing good sleep, hydration, and proper nutrition are all low-hanging fruit to start solving the tightness conundrum. From there, apply a good dose of general strength training, while splicing in whatever stretching and mobilizing variations you feel are optimal.

I don’t believe stretching, in any form or fashion, is necessarily good or bad. Stretching won’t be a standalone solution for most athletes; equally, it should be a part of almost every athlete’s programming. Restorative treatments or modalities, however, should be included when they’re demanded. Being passive or retroactive with recovery won’t cut it for any athlete and applying general methods to specific limitations will inevitably shortchange the athlete. Be general when you can but specific when you must.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Schleip, R. Chapter 9 – “Water and fluid dynamics in fascia.” Fascia in Sport and Movement. Schleip, R, Wilke, J. Handspring Publishing, 2021, 117–127.

2. Stecco, C. Pirri, C. Fede, C. Yucesoy C., De Caro, R., and Stecco, A. “Fascia or muscle stretching? A narrative review.”Applied Sciences. 2020;11(1): 307.

3. Behm, D. and Chaouachi, A. “A review of the acute effects of static and dynamic stretching on performance.” European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2011;111(11):2633–2651.

4. Frenzel, P. Schleip, R. and Geyer, A. “Responsiveness of the plantar fascia to vibration and/or stretch.” Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2015;19(4):670.