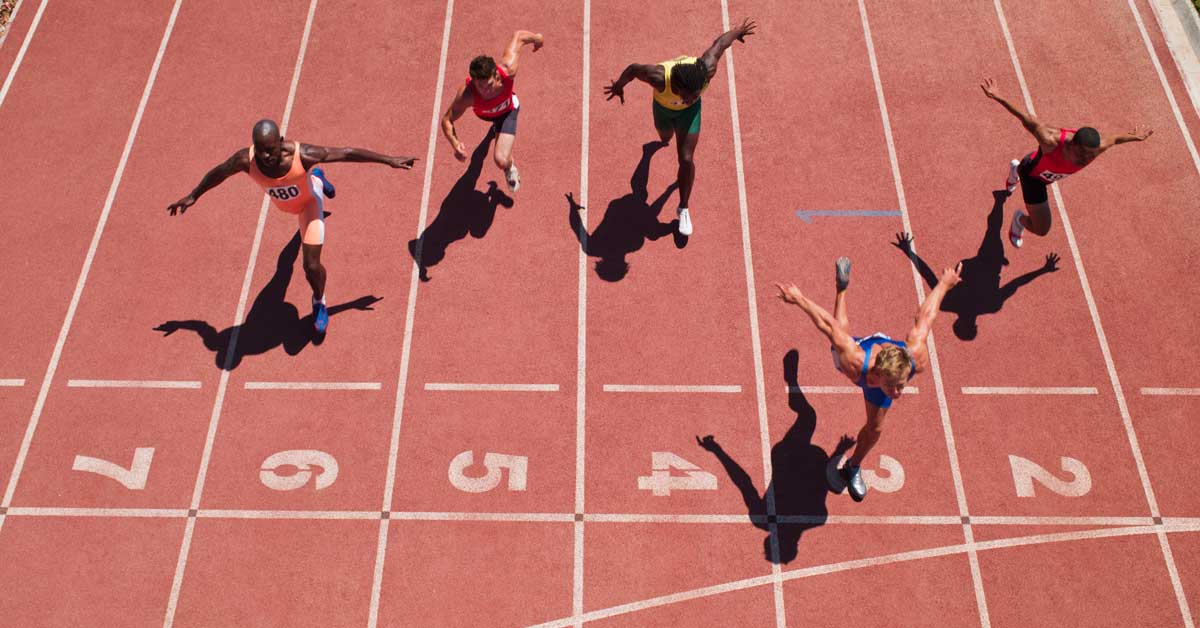

We all know the meet. Four to six big teams show up together on an April Saturday afternoon for a no-limit entry track meet. The last heat is scoring, but the rest are non-scoring. Some people find a way to kill the 45 minutes of 100m dashes with their meal ticket or find another coach to talk to about the problems of post-COVID-19 coaching. While I eat during the three heats of the 3200 and reapply sunscreen during the five heats of the 1600, I like to plant myself midfield right next to the track and watch the 18 heats.

As I watch athletes project their mass down the track in various sprinting styles, I wonder what can be done to make the 12.5 into an 11.5.

I know there are basic things that can be done to start making progress down that road. Stuff that I have written about in the past: crossover feet, heel strikes too far in front of the body. And we know how to deal with these issues with mini-hurdle runs and stiff-legged runs (Paytons or Prime Times). But if it is halfway through the season, and the drills aren’t catching, maybe we should start looking at some other things.

Posture is the first thing that jumps out from the early heats of the 100. Something that is so basic that we forget to deal with it in practice, drills, or even weightlifting. Why does posture fall apart? When the system is red-lined, like in a full sprint, there is a hierarchy to movement.

After breathing and keeping a horizon (and few other things), not falling is important. Safety is far more important than speed. The body quickly assesses what muscles can support the movement. It will shift so the muscles used are the ones that can support the body safely. They are not always the most powerful or efficient but the safest. If you don’t think this is true, watch how fast posture and gait change when someone injures themselves while sprinting.

In a full sprint, not falling is important. The body quickly assesses what muscles can support the movement and shifts so the muscles used are the ones that can support the body safely, says @korfist. Share on XOnce we are safe, we will move toward our target. This is why different body parts sometimes move toward the finish line. We are throwing as much as we can at where we are going. This is the reason when you blindfold someone and have them sprint, their form changes. Or when a happy 3-year-old is sprinting for fun and running fast, they always seem to have good form. Form becomes more natural when we eliminate intent.

There are three sections of the spine:

- Cervical

- Thoracic

- Lumbar

All three work together to counterbalance each other. The more an athlete can keep a neutral spine, the better the body performs. A good athlete can keep a neutral spine in various positions. A really good athlete has the ability to use their spine to create more power in their movement.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9054]

Where to Begin?

Let’s start in the middle. I know it is a strange place to start, but it is the place that controls both ends—really, it’s no different than an axle with two wheels on each side. The stiffer the middle, the more stable the ends will be. Same with a runner: if the middle is not stiff, both ends will compensate to get the body to the target.

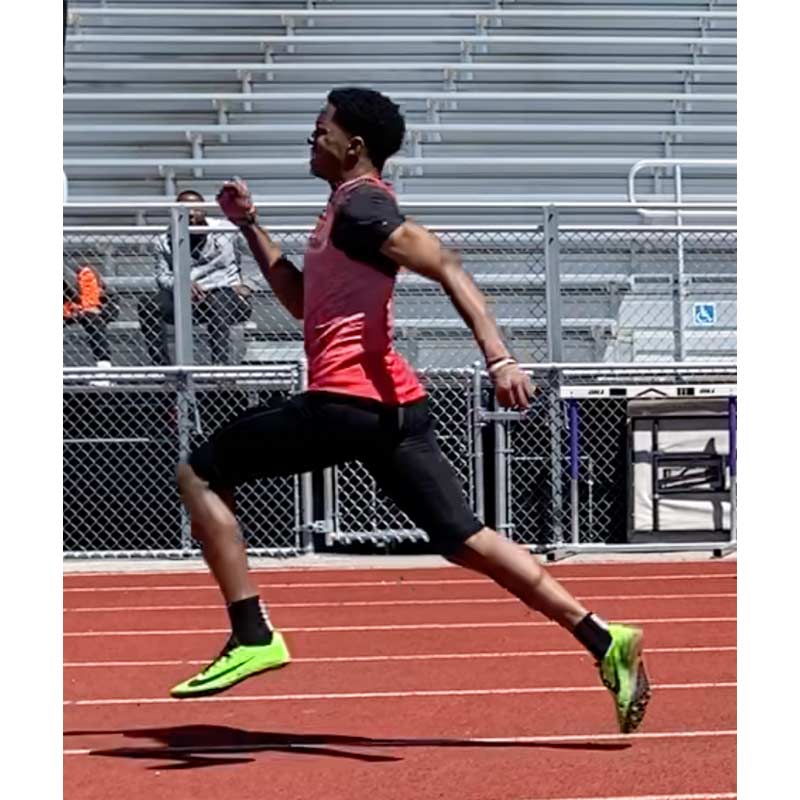

In the case of the runner above, to gain extension, he loses pelvic control. As you can see, his right pelvis is over-rotating, which leaves his right leg long in the push. A telltale sign is that his right knee is behind his glute. This creates the problem of a longer time to swing the leg through, and the knee cannot get to the needed height for a good, fast tangential velocity.

Here are some effects of a wobbly middle. The first impact is the head.

If the body follows the head, the net propulsive forces are reduced with the 12-pound weight falling backward. If a coach asks the athlete to stand in place with the same head position, they will fall back.

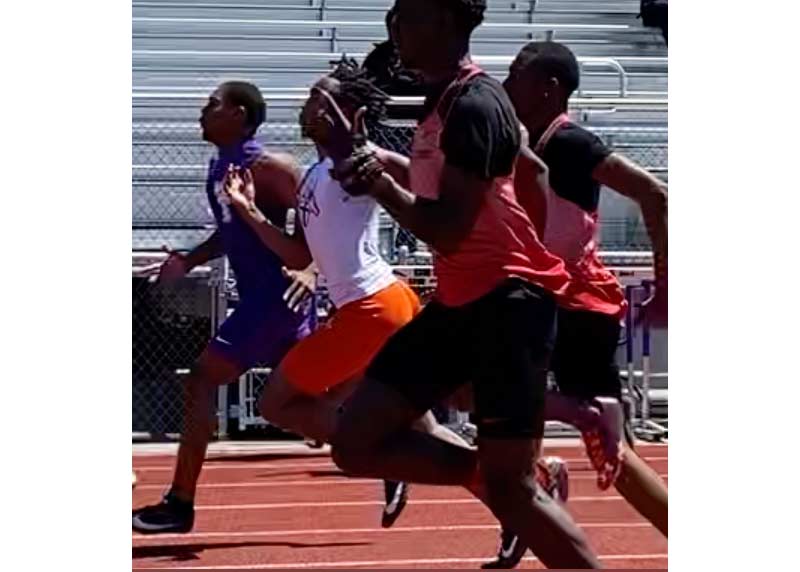

Below are examples of what happens of what happens on the pelvic end of the axle.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9056]

Why Does This Happen? We Do Core Every Day!

You may be using the core exercises, but not properly. How often do you see people doing planks and dropping their head or pelvis? How often do you see side planks with the chin sticking out to balance or the spine not neutral in three planes?

Once you have a base of spinal control and strength, try challenging the spine with movement. Ask the spine to control itself in unpredictable scenarios, says @korfist. Share on XWhen doing any of your running drills, how often do you focus on posture? Once you have a base of spinal control and strength, try challenging the spine with movement. Ask the spine to control itself in unpredictable scenarios. Enter the water bag. Try your drill and sprints with a water bag on your back. The spine has to constantly adjust.

For more advanced drills, I will be presenting at the University of Minnesota with Dan Fichter and Cal Dietz in July and will cover postural progression in detail. You can find sign-up details for the clinic here.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF