Marco Airale is an Italian professional track and field coach, as well as a physiotherapist (BSc) and osteopath (DO). During his early career, he founded Eracle Academy, a performance development center for track and field. As international experience, he worked in China as a performance therapist for Coach Randy Huntington and his group of sprinters and jumpers. He was assistant coach to Rana Reider, with whom he participated in his first Olympic Games. He currently coaches a professional group based in Italy.

Freelap USA: You have been mentored by some of the world’s leading coaches with respect to sprints and jumps. What are some commonalities within the training that elite coaches prescribe to their athletes?

Marco Airale: The biggest commonality I saw between the elite coaches I have spent time with is how they structure their training. In 2019, I moved to China to assist Randy Huntington as a therapist for his athletes. The way he structured his training correlated with what I had read in articles on how many U.S. coaches set up their training using daily themes. For example, there may be an acceleration day, a maximum velocity day, and a tempo/special endurance/speed endurance day. This was very similar in structure to what Rana Reider was doing in Florida when I moved there a year later.

In Italy, sessions are designed with the type of metabolic stress in mind. American coaches tend to design their sessions based on biomechanical and technical themes, says @AirMerk. Share on XIn Italy, training largely tends to be based on the metabolism, and sessions are designed with the type of metabolic stress in mind, with the addition of a lot of drills, some of which are arguably unnecessary. The leading American coaches tend to design their sessions based upon biomechanical and technical themes. For example, one day may have an acceleration focus, while another may have a maximum velocity focus, and the metabolic work gets covered on separate days with an emphasis on tempo or special endurance.

This isn’t to say that there is no technical instruction in Italy, but my experience was that the techniques were taught during a metabolic workout. For example, a short speed endurance workout involving many repeat 60-meter efforts may also be seen as an opportunity to work on starting technique.

Freelap USA: Along the same lines, at every level, different coaches use varied methods with success. What are some of the differences you’ve noticed in the programming among the world’s best coaches?

Marco Airale: I think coaches can be broadly divided into scientists and artists, and while the great coaches apply both science and art, there are biases. So, some coaches may write their program based upon the science and stick to it strictly, while another coach, still writing their program with the science in mind, may design the training in a way that allows them to be more flexible with the delivery of the program, allowing their artistic side to be used more easily.

The “scientists” are more likely to record and measure training variables and look for quantitative improvements, and the “artists” are perhaps more likely to cue effectively based upon an intuition of what the athlete needs to feel to get an improvement.

I think coaches can be broadly divided into scientists and artists, and while the great coaches apply both science and art, there are biases, says @AirMerk. Share on XIn 2011, I was an amateur long and triple jumper, and I got the opportunity to train in Spain. My experience there was that the jump training took precedence, and there was a little bit of additional sprint training. However, the U.S. coaches I have seen coaching jumps tend to flip that, and sprinting is the bulk of the program, with a little bit of additional jumping.

This could be because track and field is seen as more of an individual sport in Europe. In the U.S., particularly in the high school and collegiate systems, track and field is a team sport, and the jumpers, in many cases, will run individual sprint races and/or relay legs. Therefore, sprint training needs to be a greater focus for jumpers in this system, which could lead to a culture or tradition of how they are developed.

Freelap USA: Cueing is an area that has been well researched, and different coaches have different aspects that they focus on to hopefully get their desired results. What areas of the stride cycle do you see as important, and how do you cue for this?

Marco Airale: My background is in physiotherapy and osteopathy. While I wouldn’t say my understanding of the human anatomy is perfect, I have a pretty good understanding of how it works. So, I base my area of focus—and my cues—on this.

You don’t need to worry about the ground too much, as it will inevitably come. It is impossible to fly! I think it is important to set up the positions correctly in the air from posterior to anterior, and one of the aspects I stress is to let the knee “float” forward. I use the word “float” because the iliopsoas, the main hip flexor muscle, attaches to both the femur and the lumbar spine. By cueing an aggressive hip flexion, the contraction of the iliopsoas not only lifts the knee but also causes a “collapse” in the torso, negatively impacting the athlete’s posture.

I also see the word “float” as allowing for more patience and relaxation, which I think is really important from a coordination standpoint. A muscle can only be “on” for so long before fatigue sets in and the quality of contraction is affected. This can have a knock-on effect in terms of coordination, negatively impacting the skill of sprinting.

I firmly believe the more you can be “off” or relaxed in the air, the better you can subsequently turn the relevant contractions “on” to create stiffness and prepare for landing. I emphasize this in drills because if an athlete cannot perform this at slow speeds of under 5 kilometers per hour, how can they expect to perform it at 38–42 km/h come competition, while in a pressurized environment?

Freelap USA: Daryll Neita has seemingly gone from strength to strength since working with you. What qualities has she improved that have significantly contributed to her performance? Do you have any workouts for her that you use to assess how “ready” she is to compete?

Marco Airale: It’s important to note that Daryll had made significant improvements with Rana Reider between 2019 and 2021, when she took her 100-meter time down from 11.12 to 10.93 and made the Olympic final. I had to bet on myself when starting to work with Daryll, as she was one of my first full-time athletes but already had a personal best of 10.93.

To continue her progression, I needed to be as accurate as possible. Since I had a small group, I think that helped in this regard—we were able to focus on developing more specific areas in her technique and the strength of some of the muscle groups that would help facilitate that, including the adductors and hamstrings. Overall, we continued to work on her fitness throughout the year, and what I mean by “fitness” is that there were no injury issues, and she was in consistently good health to be able to train at a high level. I have very much a “health first” philosophy. Right now, with my group, we are just starting our fall training, and my first task is to make sure that any lingering issues are resolved so I have a robust group of athletes.

I think my background is an advantage in this case, as I can be the physio for the athletes, and I can be the osteopath for the athletes. Therefore, I can help resolve potential issues and encourage their bodies to work in the way that I believe is optimal for sprint performance. Last year, with Daryll, we didn’t miss any days of training, and I believe that if we have more days where we can hit 35 km/h in training, then it makes it easier for us to hit 38 km/h when we need to in a race. Doing this consistently enables performance to be at a higher level more frequently in competitions, and I think this is what we saw last season.

With my background as physio and osteopath, I can help resolve potential issues and encourage their bodies to work in the way I believe is optimal for sprint performance, says @AirMerk. Share on XWhile her PB only improved from 10.93 to 10.90, she was able to run under 11 seconds several times in 2022 and in races with a lot of pressure. She maintained her composure and ran some of her fastest-ever times in the presence of some of the all-time great sprinters when at the pinnacle of their careers. If you look at Monaco, for example, Daryll ran 10.91 in a race that was won in 10.6, where 10.96 would have only got you seventh and last place!

In terms of assessing whether or not Daryll is ready to roll, I do not do test sessions or anything like 150-meter or 80-meter time trials, but I use my experience to see whether or not the work is trending in a positive direction.

Freelap USA: Could you please share an example of a training week from the autumn and from close to the competitive season? What are the key trends that you progress between these two times of the year?

Marco Airale: In my answer to your second question, I spoke about how coaches may be more comfortable with the science or the art, and I definitely feel more comfortable with the science. Therefore, my programming structure does not change throughout the year. Year-round, my program looks like this:

-

Monday – acceleration

Tuesday – longer running

Wednesday – maximum velocity

Thursday – longer running

Friday – acceleration

Saturday – longer running

There is progression across all these sessions, however. Acceleration work is predominantly skills-based in the autumn, working on biomechanics and hitting the angles I want to see. I may include some resisted sprints—which can help facilitate this.

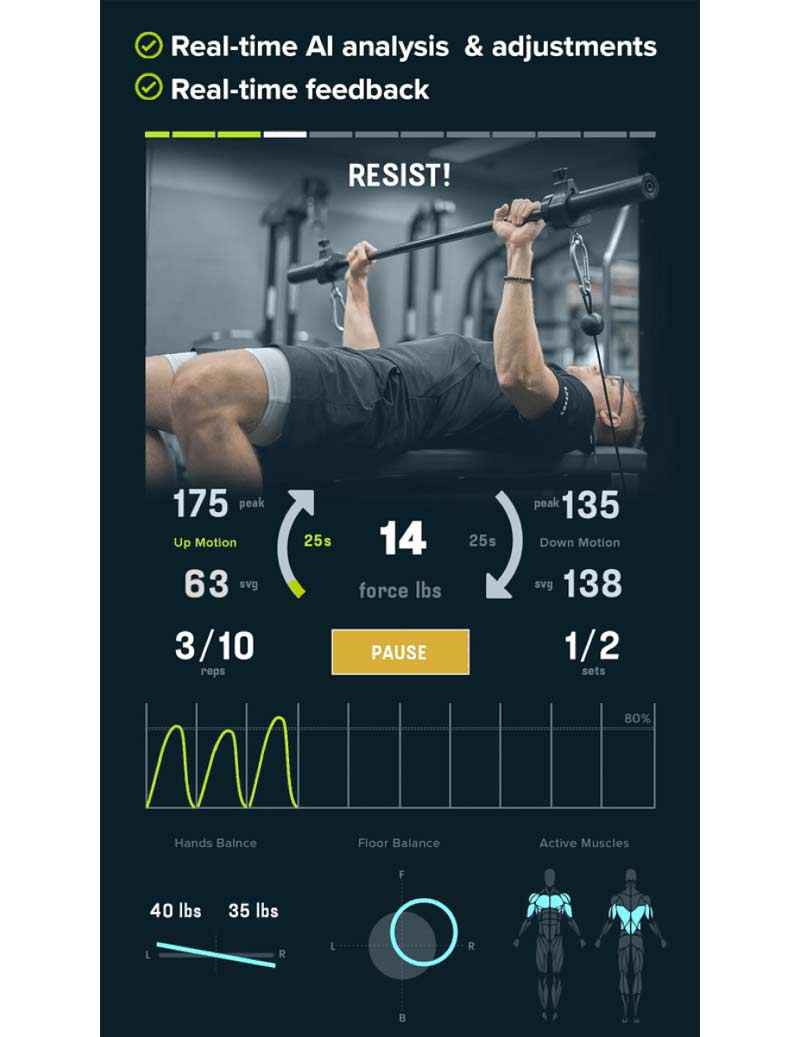

When I set up my professional group back in Italy, one of the first things I bought was a 1080 Sprint, as it allows me to be very precise in terms of the resistance I offer the athlete in these workouts and in the assistance I offer them in maximum velocity workouts (but we’ll come to that later). As the annual training cycle progresses, the intensity and speed of acceleration work increase, and things like spikes, blocks, and competitive starts are gradually introduced.

The progression is very similar in the maximum velocity sessions as it is in the acceleration sessions, starting with a large degree of technical focus. So, maximum velocity sessions do not always include high-speed running but drills or slower runs working on hitting the positions I want to see. As the training year progresses, the intensity and speed of the runs progress fairly linearly. Shortly before the competitive season, I may use the 1080 Sprint for assisted sprinting, offering a supramaximal stimulus.

The longer running progression is pretty typical, going from extensive tempo to intensive tempo to special and speed endurance. As the intensity rises, the volume decreases, and this is perhaps more reflective of the traditional Italian method of preparing a sprinter, starting with aerobic development before targeting the lactic system.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Dr. Chad Herring joined the Florida Atlantic University Football program in May 2022 as the Director of Sports Science. Prior roles include serving as the Director of Performance for DIA Sports Performance (private sector), Head Strength and Conditioning Coach at Angelo State University (NCAA Div. II), and a seasonal Strength and Conditioning Coach for the Tri-City ValleyCats (Houston Astros minor league affiliate). Chad earned his B.S. from Ithaca College, M.Ed. from Angelo State University, and Ph.D. from the University of Central Florida (UCF). While at UCF, he worked on various sport science projects with the Men’s Soccer, Women’s Rowing, and Women’s Volleyball teams. Additionally, his dissertation was completed with the UCF Softball team, titled “Utility of novel rotational load-velocity profiling methods in collegiate softball players.”

Dr. Chad Herring joined the Florida Atlantic University Football program in May 2022 as the Director of Sports Science. Prior roles include serving as the Director of Performance for DIA Sports Performance (private sector), Head Strength and Conditioning Coach at Angelo State University (NCAA Div. II), and a seasonal Strength and Conditioning Coach for the Tri-City ValleyCats (Houston Astros minor league affiliate). Chad earned his B.S. from Ithaca College, M.Ed. from Angelo State University, and Ph.D. from the University of Central Florida (UCF). While at UCF, he worked on various sport science projects with the Men’s Soccer, Women’s Rowing, and Women’s Volleyball teams. Additionally, his dissertation was completed with the UCF Softball team, titled “Utility of novel rotational load-velocity profiling methods in collegiate softball players.”