When I entered the strength and conditioning field, I was told the best way to improve the vertical jump is to squat. If our squat numbers improved, our verticals would follow—and, up to a point, this is absolutely true. For athletes who are relatively weak or relatively young, developing stronger legs (along with a heightened nervous system) will lead to better jumps.

Over time, though, I found this wasn’t always the right solution. Athletes would increase their squat, but their jumps would flatline. These athetes were strong in the squat, so why weren’t they jumping higher? I saw this play out time and time again. Once my athletes obtained certain strength levels, jumping ceased to improve.

On top of that, I used to only measure jumps every 8-12 weeks. If jumping is considered a key performance indicator (KPI) in our program, why wait three months to see if it improved? What if their best day was actually three weeks into the program? What if the athletes had a bad week and that’s when we tested?

I want to know how we’re performing every week and if my program is doing what I say it’s doing.

I want to know how we’re performing every week and if my program is doing what I say it’s doing, says @coachrgarner. Share on XEventually, this led me to the works of Joel Smith, Cal Dietz, and Chris Korfist. These coaches drastically influenced my thought process on jump development because they were the first coaches that said heavy squats aren’t the only way to develop the jump. Instead, they discussed a variety of techniques, biomechanical and physiological differences, and key movements needed to be a successful jumper.

In my eyes, this shifted jump development from strictly a strength issue to a multi-faceted problem requiring multiple solutions. If you want to learn more about jump development and technique, I highly recommend “Vertical Foundations” by Joel Smith.

Improving the Vertical: This Should be Easy, Right?

In sports performance, the two hardest skills to improve are sprinting and jumping. These are also the most important skills to master for on-field success. Skill is defined as “the ability to do something that comes from training, experience, or practice.” For any skill, it takes substantial time, effort, and technical knowledge to create long-lasting change.

The difficulty in training these skills stems from the fact that athletes have been running or jumping their entire lives. This means techniques, habits, and neural pathways are engrained long before coaching interventions occur (which can be a good thing). In my experience, the average male and female will jump 23-25 inches and 18-20 inches respectively. Once they reach this point, we’ll see a stall in progress if we’re not training with a purpose.

For jumping-based sports like volleyball, an athlete’s technique and habits will be reinforced countless times in practice and games. An outside hitter can jump up to 120 times a match, and for players on the club circuit who play six games over a weekend, that’s 720 jumps. This further ingrains neural pathways and solidifies jumping technique and outputs. On top of that, the majority of these jumps will be submaximal, which may decrease their vertical over time. If the athlete doesn’t have a strong foundation of strength and technique, this could lead to problems down the road.

For jumping-based sports like volleyball, an athlete’s technique and habits will be reinforced countless times in practice and games, says @coachrgarner. Share on XIn most cases, the responsibility of increasing the vertical jump falls on the shoulders of sports performance coaches because jumping is typically viewed as an outputs (force) issue. Although this is a factor, it does not fully encapsulate jump development. There are a variety of strategies which can be employed to train jumping (such as techniques specific to muscle- versus tendon‑driven athletes), and it becomes even more complex as we dive into standing versus approach jumps.

Within the weight room, I believe the coach’s focus should be on developing the standing vertical, as this is the floor of jumping potential while the approach jump is the ceiling. The approach jump is a technical-driven skill which requires significant time and effort to improve. Meanwhile, the standing vertical has a lower technical barrier and is a reflection of raw power which makes it a useful tool to measure the impact of a training program.

This leads us to our main question: How do we improve a skill that has been performed thousands of times?

We refine technique, strengthen key muscles and joints, practice jumping skills, and measure jumps regularly.

Refining Technique for Takeoff

Technique is the most influential factor in improving jump height. No matter how powerful our athletes become, they cannot out-jump poor technique. The same goes for any skill in sport. When we clean up technique, athletes automatically jump higher.

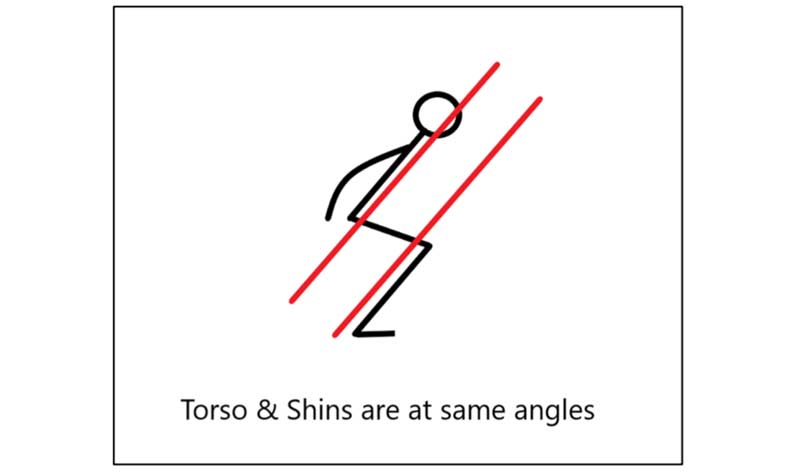

When we clean up technique, athletes automatically jump higher, says @coachrgarner. Share on XMaximizing jump height begins with refining technique at the bottom of the jump. By optimizing this position, our athletes have better chances to be successful on takeoff. The goal is to have the torso and shins at the same angle at the bottom before pushing upward, as shown in Figure 1. I learned this concept from Chris Korfist, and now it’s the first thing I notice when watching jumps.

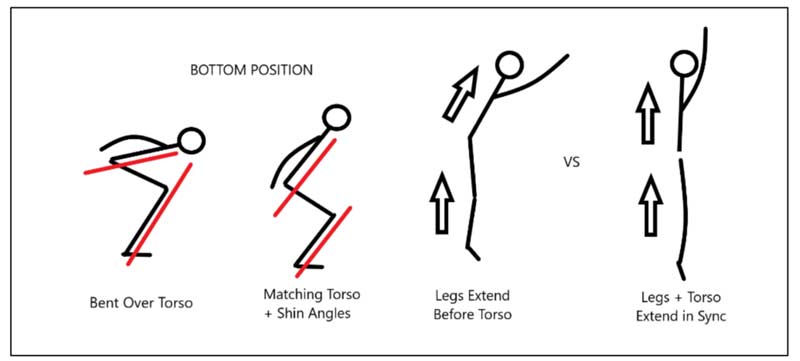

When athletes jump, particuarly poor to average jumpers, typically their torso is bent over while their shins are more upright (see Figure 2). Instead, we want to see their torso and shin angles matching, knees over toes, and a push from the ball of their foot into takeoff. The most explosive actions in sport are the result of knees over toes and force from the balls of the foot.

Why is this important to jump height?

By syncing the torso and shin angles at the bottom, the athlete is setting up for a syncronized takeoff, which makes them leave the ground faster and ultimately get to the point of attack faster. If they are bent over, then the torso has to travel further upward before the legs begin extending, leading to an inefficient and slower takeoff. In sports, we want to improve our ability to display power quickly by limiting the amount of time it takes to complete explosive movements.

In sports, we want to improve our ability to display power quickly by limiting the amount of time it takes to complete explosive movements, says @coachrgarner. Share on X

Once we establish a solid bottom position, we need to shift our focus to the takeoff. The key to an explosive takeoff is syncing up the torso, arms, and legs when leaving the ground. All of the athlete’s body parts should be fully extended as they are jumping. By doing so, all of the body’s energy will be unleashed at the same time.

The arms play a significant role in aiding the jump. Their main job is to make the body “lighter” as we’re driving up. Think of the arms as serving the same purpose bands do for band-assisted jumps. The momentum of the arms allows the legs to uncoil faster than they would normally. However, if the legs extend before the torso and arms, then the athlete’s feet will leave the ground before they are finished applying all their potential momentum. This is why an athlete’s jump dramatically improves when they start jumping regularly. As they get a feel for it, they’ll begin syncing up their arms, torso, and legs upon take off, leading to higher and faster jumps.

Note: When measuring standing verticals, athletes tend to over-exagerrate the dip, which can lead to an extremely bent over torso as shown in Video 1. However, they can still have an incredible jump. The athlete in the video has a standing vertical of over 40”, but is spending more time on the ground than what is available in sport. This is useful in terms of total-body development, but not for specifc sport application—something to consider when developing the jump.

[vimeo 653010703 w=800]

Video 1. This is a 40+” vertical on a Just Jump Mat. As you can see, he over exaggerates the dip, but still jumps well.

Isometrics Set the Floor

One of my mentors always says that “eccentrics and isometrics develop and concentrics express.” If we’re not training all three phases of the muscle contraction, then we’re not developing our athletes optimally. Eccentrics increase strength potential and the ability to absorb force. Isometrics improve the body’s ability to withstand and reapply force, and recruit more muscle fibers at once. Isometrics provide a powerful stimulus with two significant benefits to jump development:

- Isometrics raise the work capacity that our tendons and muscles can handle. With standard repetitions, we’re training the weakest position of the movement for a split second. After several reps, there’s only a few seconds of full tension at the weakest point. This means the amount of capacity developed is limited. With isometrics, we’re placing constant tension on the muscles and tendons, meaning every second spent in the position is causing a training effect while raising capacity.

- Isometrics improve the structure and function of tendons leading to healthier athletes.1 When we hold positions, our muscles are continuously contracting; as they’re contracting, the muscles are shortening, but the tendons are lenghtening. The slow lengthening repairs the tendon’s structure, leading to improved function and longevity. This is opposite of what explosive actions do to tendons, as they improve stiffness (which leads to higher jumps). As sports performance coaches, we must balance between explosive movements and isometrics in order to keep our athletes healthy over the long run.

Key Isometric Movements

We have three isometrics that are staples in our program:

- Spring ankle series

- Split squats

- Mid-thigh pulls

The spring ankle series, developed by Chris Korfist and Cal Dietz, strengthens the feet, ankles, and knees while teaching the proper bottom, middle, and full extension positions of the jump. Studies have found that isometric holds strengthen the joints 10 degrees above or below the given angle. By using various heights, the spring ankle series develops the entire spectrum of jump depths and joint angles needed to be a successful jumper.

[vimeo 653011688 w=800]

Video 2. Spring Ankle Series Position 1 & 2. Notice how the shin and torso angles are matching. This reinforces the bottom position we want to see in the jump.

The key to implementing this series is matching the torso and shin angles, further engraining proper positioning and strengthening the muscles and tendons at the specific joint angles. We have to coach this up every day because athletes will struggle to maintain posture or keep the knee over the toe. Posture equals power. When introducing this:

- Start with 3-5 sets of 10 seconds, which keeps movement quality high.

- Each week, add 5 seconds until you reach 30 seconds.

- Once they’re able to hold the position for multiple 30-second sets, start over at 10 seconds and add load.

Isometric split squats provide a high return on investment because they train several areas at once. Depending on your goal, these can be performed as yielding, overcoming, or oscillating isometrics. Yielding is the preferred method for teaching positioning and posture. For maximal effort, overcoming is the way to go. My suggestion is to perform yielding isometrics until the athletes have mastered the position, and then introduce the overcoming variation.

Isometric split squats provide a high return on investment because they train several areas at once, says @coachrgarner. Share on XIn our program, we perform isometric split squats with the front heel elevated so the athletes are strengthening their feet, ankles, and calves. They are also actively pulling in their front foot to contract the hamstrings, which improves their strength and capacity. For the rear leg, they are stretching their hip flexors while driving the big toe into the ground, leading to improved mobility. We work up to holding this position for 60 seconds, and then we can add load and shorten the time. If I use this as a warm-up, we’ll hold the position for 30-60 seconds with just bodyweight. If this is part of the workout, we’ll add load and hold for 10 seconds or less.

Mid-thigh pulls are a powerful overcoming isometric. This movement creates a total body training effect and elevates the nervous system. Before implementing this movement, make sure the athletes have strong foundations in posterior chain development and can maintain good posture when applying maximal effort. Remember, posture equals power. The last thing we want is for their backs and shoulders to be too round while they are pulling against the bar.

Although this isn’t a variation I use often, I’ll go through phases where athletes perform this once a week within a circuit. My suggestion is to perform 3-5 second pulls with a 3-second build up. This means athletes will slowly build up to max effort over 3 seconds and then pull as hard as they can for 3-5 seconds.

Concentrics Raise the Ceiling

Concentric movements refine the nervous system and display max outputs. Concentric actions need to be smooth as they’re what are the most visible in the end. For concentric power and strength of the quads and glutes, there are countless movements and strategies to use. As the coaches, it’s our job to determine what the best method is for our athletes. We’ve heard coaches say “the best method to use is the one you believe in” and the same applies here.

The main lower body movements in our program are the split squat and trap bar deadlift. I believe these movements are the best options to train the lower body, because we’re using both unilateral and bilateral positions. Unilateral positions are arguably more athletic in nature, but bilateral positions may transfer to the jump more effectively. By using both, we make sure our athletes are getting a well-rounded program.

Unilateral positions are arguably more athletic in nature, but bilateral positions may transfer to the jump more effectively, says @coachrgarner. Share on XIn our program, the split squat is considered our strength movement due to the time under tension and the amount of load our athletes can handle in this movement. I predominately load split squats in the strength zone (>80% relative intensity or RI) for 1-5 repetitions, but we’ll also use lighter loads for power development.

I prefer split squats because it takes the low back out of the equation, and I’ve never had an athlete be unable to perform them due to mobility issues. The learning curve is minimal and most athletes are able to handle more weight in a unilateral squat versus bilateral squat. In addition, we can implement a floating heel which further strengthens the feet, ankles, and calves.

Most athletes are able to handle more weight in a unilateral squat versus bilateral squat, says @coachrgarner. Share on XFor trap bar deadlift, we typically perform sets in the power zone (60-80% RI), but we’ll also use loads greater than 80% RI for 1-5 repetitions to train strength qualities and potentiate the nervous sytem. If we’re training heavy squats during the week, we’ll keep our deadlift lighter and vice versa.

Due to the high handles on the bar, most athletes will be in a half or quarter squat position, which is exactly what we want. The bottom position of the jump will be around these depths. By using the trap bar, we’re training the body to produce high levels of force at joint angles that align with jumping.

Measure and Track Jumps

In any training program, we must measure and track what we deem important. What we measure is what improves. With technology like the Just Jump Mat available, jumps are easier than ever to track. In our program, we use the Jump Mat almost every day, and we can quickly measure a room of 30-40 athletes without any disruption in training. This data shows us how our program is impacting our athletes, but also tracks the readiness of each individual.

What we measure is what improves, says @coachrgarner. Share on XWe can use this data to guide our programming decisions as well—the more data points we have, the more informed our decisions can be. If we’re seeing a downward trend in jump height, do we need to switch up modalities or are the athletes just tired? As numbers rise, we know what we’re doing is working and we don’t need to make any changes until we see stagnation or regression.

As previously stated, jumping is a skill; we need to let athletes practice and train this reguarly. Our athletes will perform either broad or vertical jumps every workout as part of a circuit or superset. This gives us 5-8 high quality jumps every session, with each one being measured. By incorporating the jumps into a circuit or superset, we’re potentiating the nervous system which leads to better performance over time.

At the end of the day, what’s the best way for athletes to improve their jump? Let them jump frequently, measure every jump you can, and progress accordingly.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Resources

1. Oranchuk DJ, Storey AG, Nelson AR, Cronin JB. Isometric training and long-term adaptations: Effects of muscle length, intensity, and intent: A systematic review. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2019