[mashshare]

In-season training at the collegiate level is a balancing act between player development and team success. On the one hand, you are dealing with 18- to 24-year-old athletes in the prime of their physical development life. The physiological progress that is possible with this specific population is about as good as it gets, on paper at least.

On the other hand, when you work in the collegiate setting, especially when you are on staff with a specific team, the primary goal of everyone associated with the program is to find a way to win games. Player development matters according to the program, dependent on team culture and provisionally on buy-in or emphasis by the head coach/GM/check writer. Regardless of the situation you find yourself in as a performance coach, a balancing act must occur in order to optimize both sides of the coin. If done right in a model that values high performance, you can optimize readiness and sport performance, while still allowing for technical, tactical, psychological, and physical development over the long haul.

Balancing the Goals of Winning Now and Long-Term Development

The key to successfully walking the tightrope between long-term development and short-term success lies, of course, in great communication and collaboration, in an environment devoid of “silos,” where everyone is on the same page. This admittedly “unicornian” example of a perfect scenario probably doesn’t ever completely exist, but in a setting where all parties at least continually strive to reach excellence, high levels of sustained success become the standard, rather than the exception. It is within this model that we, as performance coaches and sport scientists, hope to operate, while managing the bumps, bruises, fatigue, soreness, and monotony.

My current setting is a system that we have grown and developed over time, and it is a mixture of communication, trust, science, art, love, accountability, and a shared desire to continually improve. There is no “one thing” that we do that is the answer to the riddle of managing athletes from a development perspective and, at the same time, ensuring that performance capabilities are high week after week. Instead, we have a holistic model that attempts to encompass multiple factors and eventually allows for more informed decisions by all individuals involved, as to what the appropriate action might be at any given time. This isn’t to say everything is smooth sailing, that wins and player development come easily, or that there aren’t bumps in the road. The reality is that these things get harder and harder to achieve over time, but I can say without a doubt that our expectations are high and our standard is passed down and pushed up year after year.

Creating a Real-World Monitoring System

The process by which we operate has several different components, all equally important to the whole and none more important than the other. What we do from a physiological as well as subjective monitoring perspective allows us to better understand the stress we apply to our athletes, and how they adapt (or don’t). It provides context and color to the ever-looming debate over how much is enough, whether more or less is better, and what the physiological result of our training and competition actually is. It informs, but does not dictate, future action. “Front end monitoring” as we call it, simply provides information.

Athletes don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care, says @DMcConnell29. Share on XMost importantly, this first layer of data allows for conversation, both with the athletes and within the staff. Nothing creates more buy-in with an athlete then them believing you genuinely care and have their best interests at heart. Difficult conversations that come from a place of mutual understanding and trust can have broad and deep positive implications. They don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care.

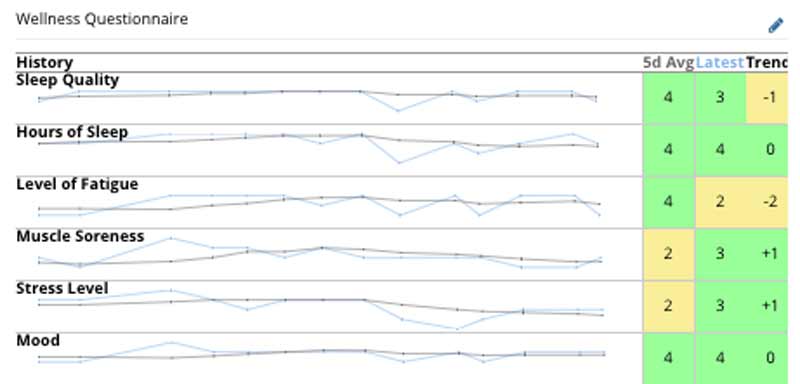

A standardized, consistently applied, subjective questionnaire is the first line of defense in our front end, allowing us to gain insight before training or practice on a daily basis, as well as identify any red flags that warrant a follow-up with the athlete. This might be the simplest and most important piece of data that we collect, as it gets us real-time data that we use to make acute adjustments.

The next layer in our attempt to quantify stress and the resulting adaptation—and ultimately navigate the inevitable bumps, bruises, and fatigue—is to utilize HRV daily. This allows us to gain a wider view regarding “readiness” by gathering information about the relative state of the autonomic nervous system. We don’t make rash decisions based solely on HRV readings on a day-to-day basis—there is too much noise in the signal with our setup.

While we are consistent and have a standardized protocol, the reality is the data we gather can never be completely clean. This is because it happens in a group setting in our Hockey Performance Center, sometime after the athletes have gotten out of bed and made their way to the arena. That being said, the data remains valuable over the long term from a trend analysis perspective, and adds a layer of feedback on top of our subjective data to evaluate adaptation. Just as importantly, it sparks conversations with the athletes when necessary.

Creating a Routine and Readiness to Train Workflow

The last layer on the front end is simply having the athletes weigh in every morning. This basic, time-tested routine provides a myriad of benefits. First, it allows me as the coach (and the athletes individually, once we’ve educated them) to monitor hydration status simply by referencing the previous day’s weigh-out number. The athlete should return to the same weight as the previous day; if they don’t, they have not taken the necessary steps to rehydrate since the last physical event.

Having athletes weigh in every morning is a time-tested routine with a myriad of benefits, says @DMcConnell29. Share on XSecond, it obviously provides long-term trend data on weight gain or loss, either of which may be positive or negative depending on the athlete and the situation. And third, weighing in daily emphasizes to the athlete the importance of body composition and hydration over a long and grueling season. As Dan John has said, “If it’s important, do it every day.”

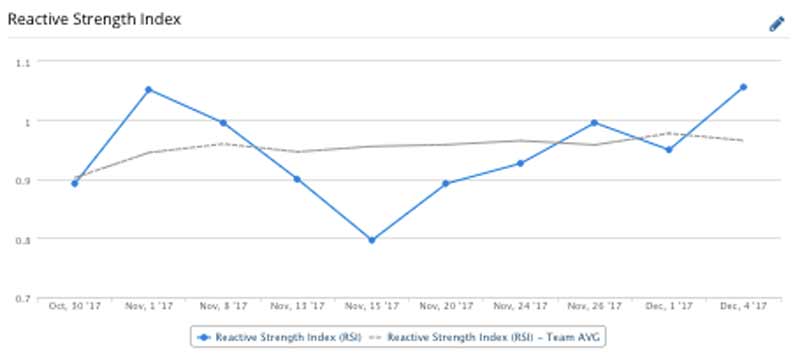

The last piece of the front end is to utilize RSI as an autoregulatory tool. This approach is by no means foolproof, but it has proven to be a reliable workaround in our setting to objectively quantify CNS “readiness,” while at the same time appreciating individual differences in workload and overall fatigue. In a nutshell, we use the RSI score from a drop jump prior to lifting sessions to adjust the loading our athletes will perform.

Based on a 30-day rolling average, if an athlete’s current RSI score is more than a .5 standard deviation above their norm, we assume that they are “well recovered” and that their system is in a good place to push development. Those athletes scoring above this threshold will increase the load in their primary exercises for that training session by 10-20 pounds. If they score within their “normal” range (within .5 to -.5SD), they will simply continue to train off their prescribed percent of 1RM. If they are below .5SD, they will cut some volume, as we take that score as an indicator that they are not firing on all cylinders and today might not be the best day to hit the gas pedal.

Psychology trumps physiology every day, says @DMcConnell29. Share on XThe caveat to this is that any athlete who scores in the “Red” must first talk to me before adjusting their loads. If they tell me they feel great and don’t want to cut anything back, I will more than likely honor their desire and allow them to train as normal. Psychology trumps physiology every day. I want to cultivate a culture of effort and accountability, and if an athlete wants to get after it, I will probably celebrate that.

Back-End Analysis for Strength and Conditioning

The flip side of “front end monitoring” is “back end monitoring”: gathering, analyzing, interpreting, and understanding the data we collect from a physical output perspective. This gleans invaluable insight into the response to training and competition. If all stress is stress, it is imperative that we measure what we can to try to better understand the implications, so that we can improve our future application of that stress.

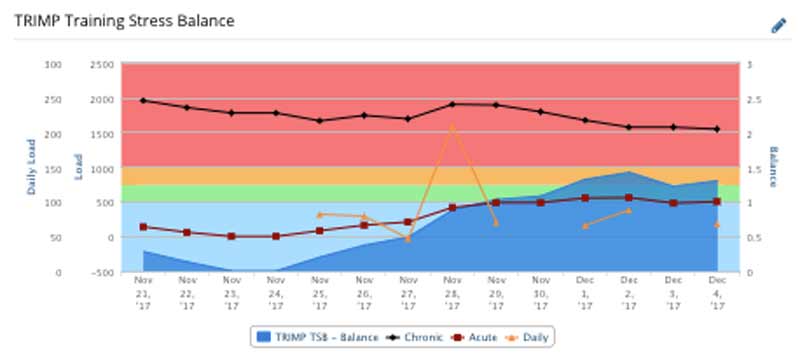

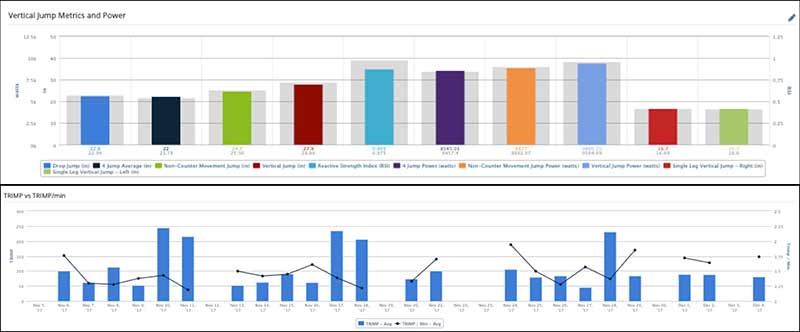

The back end is about finding out what happened. Without this layer, load management would simply be a guessing game. This can come in many forms, both subjective and objective, shorter and longer term. Daily sRPEs alongside internal training load measurements like TRIMP and intensity density provide a window into physiological load, and the athlete’s ability to handle it. These metrics should somewhat mirror each other: hard days should feel hard; easy days should feel easy. Mismatched trends can indicate functional overreaching if necessary and appropriate, or warning signs that the balance between developmental desire and performance necessity may be off.

Longer-term indicators of global strength and power development, as well as fatigue and readiness balance, are also important. We use various vertical jump metrics on a continuous and rolling basis across the season, not only to provide important data about developmental trends, but also to allow for more nuanced training within the team setting regarding individual make-up and needs. Non-counter movement, counter movement, and drop jump/RSI scores paint a picture of the relative strengths and weaknesses of each athlete. You can build a “jump profile” from this data, which will help to direct training in the appropriate area.

Weekly acceleration-based speed assessments not only microdose all important high-velocity movement—crucial to applying appropriate stress outside of competition to remain capable of handling those loads within competition—but also create and take advantage of the athlete’s competitive drive, fostering a culture of effort, excellence, and grit. Nothing gets a competitive person more excited to give a maximal effort in the dog days of mid-season training than sprinting against the clock, with teammates cheering and chirping, with past and current times posted for all to see.

The Programming of Strength and Conditioning

As we slide down the continuum from monitoring to training (they are really all one piece of the same pie, and so cannot be completely removed from each other), we arrive at loading for development and loading (or unloading) for immediate performance. This is where the meat and potatoes of the balancing act come to the table for the performance coach. Monitoring gives us information, and now we must use that info to make decisions.

Culture must be the first part of this conversation. Nothing even remotely appearing to drive development or reach optimal performance is achievable without a culture cultivated from the top down and reverberated from the bottom back up, that emphasizes, demands, and embraces effort and intelligent training. However, when this is the standard held up within a program or organization, it is up to the performance coach to appropriately guide the athletes towards this goal.

I am a firm believer that strength must underpin and set the foundation for high performance development, as well as athlete robustness, in team sports. Actual weight room loading must progress in intensity and then remain high. Consistency is key: Once the foot is off the gas pedal in-season, it’s nearly impossible to get back up to speed.

Athletes must routinely use loads between 80% and 90% to provide adequate stimulus to the organism and ensure the ability to maintain the expression of this level of force production. That said, I favor a very low volume approach. At no time in the season should there be an overload of volume or a “straining” or “grinding” to the movements of training. That is why consistency is so key. More than a week or two away from heavy loads will result in a marked increase in effort, and a decrease in velocity, of the primary exercises.

There is, of course, a time and a place to taper load and increase velocity, but I find it best to reserve this for a very narrow window at the very tail end of a season. If 85% of a rear foot elevated split squat for two reps is hard or nearly impossible late in the season, then you, as the coach, failed to apply adequate stress long before that.

Fine-Tuning the Weight Room with VBT

One tool that is a “nice to have”—but might just be a “need to have,” if at all possible—is something that allows for velocity-based training. VBT lets us autoregulate loading, but in a much more nuanced way than RSI. This is nothing new, but when it comes to managing stress and fatigue, and bumps and bruises, the ability to prescribe training by speed instead of load, and the subsequent ability to adjust sets based on an athlete’s acute abilities, is hugely beneficial.

The key is getting athletes to respect the numbers, and back off when the data says back off. At first, this is tough, as they won’t feel like they’re getting better. But over time, with enough education and buy-in, they will realize that following their nervous system’s ability, which is really just listening to their body, will result in one step back and three steps forward.

Mastering the Balance and Using Common Sense

At the end of the day, the balancing act between longer-term athlete development and shorter-term team success comes down to managing stress. It’s like Goldilocks: not too much, and not too little. Finding that sweet spot is a combination of art and science. A coach’s intuition, along with candid conversations with the right group of players, is a must, but so is the appropriate use of objective data. “Figures lie, and liar’s figure” might be true, but data can still tell a story.

Balancing long-term athlete development and short-term team success comes down to managing stress, says @DMcConnell29. #LTAD Share on XThere is no one thing, no unicorn answer, to tell you how to navigate a long season and maintain equilibrium between development and readiness. Furthermore, no season is the same. But hopefully, in the quest to achieve this goal, common sense backed up with a little bit of science will be the winning recipe.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]