In 2001: A Space Odyssey, a film released in 1968, astronauts on a spacecraft are able to call on HAL to assist them in their mission. HAL (which stands for Heuristically programmed ALgorithmic computer) is a sentient computer able to utilize artificial intelligence (AI) to carry out a variety of tasks. The crew considers HAL a dependable member of the crew, at least initially, as it can carry out a variety of tasks—including playing chess. Over the following years, AI was depicted in science fiction films in various ways, including R2-D2 and C-3PO in the Star Wars films, the various agents in the Matrix trilogy, and WALL-E.

While science fiction writers have long utilized intelligent nonhumans in their storytelling, it’s only in the last 50 or so years that AI has been within the grasp of use for humans in general. AI is commonly defined as machine behavior that would be considered intelligent if exhibited by humans, and it was initially developed as a series of “if, then” rules on what were, at the time, ground-breaking supercomputers.

Since then, AI has grown across a variety of subfields, moving from these simple initial rules to fields such as computer vision (where the machine can “see” and track various objects), machine learning, and deep learning. Alongside this enhanced AI and computing power, the concept of “Big Data” has developed, whereby vast amounts of data can be collected, processed, and analyzed to create information. In essence, as highlighted by a recent PwC executive report, we can view AI as technology that has the ability to learn, take in information, and respond appropriately.

These various subfields of AI usage have found utility across a wide range of industries, including medicine, technology (such as driverless cars), business, and the military. Many of us use AI multiple times a day, with virtual assistants such as Apple’s Siri or Amazon’s Alexa or even just predictive text on our smartphones.

Never a field to lag too far behind various innovations, sport is increasingly using AI across a wide range of areas, including elite sport, says @craig100m. Share on XNever a field to lag too far behind various innovations, sport is increasingly using AI across a wide range of areas, including elite sport, officiating (such as the Virtual Assistant Referee in football), journalism, sports medicine, and even sports betting. AI has also been used to provide a virtual competitor, perhaps most famously in the case of IBM’s Deep Blue. This chess-playing machine famously defeated the chess grandmaster Gary Kasparov in 1997 after losing an initial match in 1996.

Current Uses for AI In Elite Sports Performance

Specifically in the field of high-performance sport, AI has been used to assist in aspects such as:

- Performance analysis.

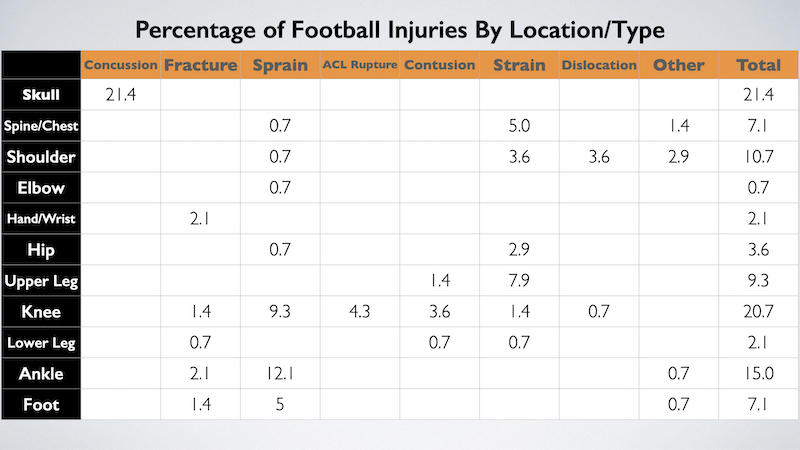

- Injury risk assessment and management.

- Scouting.

- Training outcome prediction.

- Performance prediction.

- Decision-making.

While still relatively new to high-performance sport, over the last 20 years, AI usage has grown. A recent review, published in Frontiers in Sport and Active Living and authored by a group of researchers from Germany (led by Fabian Hammes), paints an interesting picture of how AI is used at the highest level within sport. The researchers identified 540 studies that examined the topic, with football (soccer) being the sport most likely to utilize AI. This is perhaps unsurprising. Football clubs, especially in Europe but increasingly in Asia and the Middle East, have large budgets. For example, in 2021, Manchester United’s operating budget was US $745 million—a sum significantly larger than most Olympic sports receive across a whole Olympic cycle.

Alongside soccer, other sports with the greatest AI research base are cycling, tennis, and basketball—all sports with a broad appeal at the elite and community levels, says @craig100m. Share on XThese increased budgets (as well as their reputations) give clubs the capacity to bring in experts with the knowledge and ability to develop effective AI systems and processes. As an example, Arsenal was famously able to hire a data scientist who had previously worked on developing the popular game Candy Crush. Alongside football, other sports with the greatest AI research base are cycling, tennis, and basketball—all sports with a broad appeal at both the elite and community levels.

In their study, Hammes and his colleagues identified four critical areas in which AI is currently being utilized in elite sport:

- Machine Perception: This involves AI technologies being utilized for image recognition and computer vision purposes. These technology types have the potential to assist in understanding performance—both more rapidly and more deeply—then, in turn, quickly provide this feedback to the athlete and coach as a means of supporting performance. As an example, it is now possible to set up a static camera that views the whole of the long jump runway and use this in competition to provide key pieces of data to athlete and coach, including runway speed, takeoff angle, etc.

- This then allows for almost real-time in-competition changes to be made by the athlete, hopefully improving their performance. In team sports, similar technologies are often used to track player positions and distances covered, allowing the coaching team to quantify what is happening. Finally, technologies such as Hawkeye utilize machine perception to determine whether a ball was out (in tennis) or a bowled ball in cricket would have hit the stumps.

-

- Machine Learning and Modeling: Recent developments in AI have also allowed for models to be developed that can utilize large amounts of data to learn patterns, an approach typically termed “deep modeling.” This approach can be used to identify aspects that perhaps don’t seem obvious at first sight and has been used to predict the outcome of competitions, identify sports injury risk, model training response, and optimize talent development.

-

- Planning and Optimization: Building on the use of machine learning models detailed above, AI technology can also assist in sports planning. This can include planning various training processes (e.g., periodization), as well as schedule optimization.

- Interaction and Intervention: This aspect of AI usage in elite sport relates to technology that provides athletes with feedback as a means of improving their performance. This can be wearables (including smart clothing and smartwatches) and both virtual and augmented reality technologies—something I’ve written about before.

Overall, the results from the Hammes and colleagues’ study demonstrate an increased interest in the use of AI in elite sport—something I’m sure we can all attest to through experience. A second paper in Applied Sciences highlighted the increase in research interest in using AI in exercise training, going from two studies in 2006 to 22 studies published in 2019 alone. As such, it’s clear that the use of, and interest in, AI in elite sport is on the rise.

Future Applications for AI and Sports Performance

While the use of AI in elite sport is certainly growing, there are even greater avenues of opportunity for the future. Beyond the obvious aspects that require improvements—including increased validity, reliability, and usability, along with reductions in both costs and complexity—AI could revolutionize other aspects of elite sports performance.

One area of increased potential is that of wearable devices. Wearables such as wristwatches (for example, an Apple Watch) provide data; this data is then utilized to quantify aspects such as training load and physiological stress, providing key insights. This can be useful as an overall training monitoring tool but may be even more helpful in aspects such as sports injury rehabilitation, where overall load—or even load on a specific body area—needs to be carefully managed.

Wearables can also assist in quantifying body position, which in turn assists with things such as biomechanical analysis and the position of the athlete on the field of play, which can aid with performance analysis aspects such as quantifying tactical behavior. For wearables to become increasingly adopted in elite sport settings, they will need to be cost-effective, comfortable, easy to use, and able to collect valid and reliable data—all aspects that are currently a challenge.

Another major opportunity for the use of AI in elite sport is through its ability to make the vast swaths of data regularly collected in high-performance sport settings actually usable. Some of the data routinely collected in elite sport include wellness and well-being markers, competition performance and performance variables, various “key performance indicators”—such as physiological, biomechanical, psychological, and tactical markers of success—and other metrics, including climatic conditions.

A major opportunity for the use of AI in elite sport is through its ability to make the vast swaths of data regularly collected in high-performance sport settings actually usable, says @craig100m. Share on XSuch disparate data sources can be difficult to analyze, particularly in relation to each other, making the gathering of meaningful insights challenging. Added to this, AI technologies, such as video machine learning and pose estimation, further increase the size and type of data that can be collected; as technology in other areas develops, even further aspects could be added. For example, if genetic testing can increase its overall validity, it may become more commonplace in guiding training program design and identifying injury risk.

As a result, decision-makers in elite sport—which includes the coach—will have a plethora of data available to them.

The opportunity here is to make the collected data useful, something that can be driven by AI-supported technologies such as data mining techniques. AI-supported machine learning models can then analyze this data, allowing for more effective utilization of the data collected on a regular basis. In addition, such advanced statistical techniques will enable us to understand whether any data that is gathered is not useful, helping data collection to become more refined and targeted in the future.

This is a somewhat similar approach to that of precision medicine. Here, different data sources are analyzed to create more precise—and, in some cases, individualized—treatment regimes. For example, in 2018, a group of researchers utilized whole genome testing, along with a machine learning program, to identify individuals with an increased risk of coronary heart disease. To do this, they utilized 6.6 million data points per individual from over 120,000 participants. This is a staggeringly large amount of data, and such analysis would not have been possible without the assistance of AI. However, similar breakthroughs in elite sport should allow for a movement from the basic collection of data and information—the lower levels of the wisdom hierarchy—toward true wisdom.

Practical and Ethical Challenges for AI and Sports

There are, however, some barriers to the effective implementation of AI in elite sport. One such barrier is related to the last opportunity I mentioned: the use of data. Many of the potential AI-supported aspects that may enhance practice in elite sport either produce data that needs to be collected and/or stored or require a lot of data for analysis. This collection of multiple pieces of data can be subject to a variety of protections and ethical challenges, with many governments (state, federal, and international) developing legally binding frameworks and legislations that govern the collection, use, and storage of data.

An obvious example of this is the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation—commonly termed GDPR—which influences the data that organizations can collect, along with how they use and store it, with significant financial penalties possible in the case of a data breach. Along a similar vein, a recent report from the Australian Academy of Science highlighted that in many professional team sports, sufficient thought and appreciation are not given to the risk-reward ratio of the data collected and how this might negatively affect an athlete.

A further example of this is the collection of genetic information. On the surface, such an approach is attractive: our genes play a large role in determining who we are, so better understanding them should assist in guiding our approach to athlete development, particularly with regard to aspects such as future performance or training adaptation. However, the use of genetic testing and genetic information in elite sport is rife with ethical issues.

As an example, there is a common genetic variation in a gene that affects the development of collagen, a critical structural component of ligaments and tendons. Variation in this gene has been linked to an increased risk of injury. Is it ethical to use this information to select or deselect an athlete for a talent program? What is the burden on the organization for testing for this variant?

For instance, what further investigations are required if genetic screening uncovers a serious medical issue? Where would this data be stored, how secure is it, and who would have access? What happens if an athlete doesn’t consent to their genetic data being collected—can they actively be deselected on this basis? Can Under-18s even provide informed consent for the collection of their genetic information?

These questions all highlight some of the issues around data collection, the quality of which underpins the effectiveness of using any AI in elite sport.

The ethical and safety questions surrounding data collection, storage, and use may also impact the development of effective AI, says @craig100m. Share on XThe ethical and safety questions surrounding data collection, storage, and use may also impact the development of effective AI. To test that any data-oriented AI system is useful, it typically has to be “trained” to identify patterns on large data sets; this allows the AI (for example, a machine learning program) to determine which aspects of the data might serve as valid, reliable, and relevant predictors. To be effective, this requires large data sets; given the concerns discussed earlier, such large data sets may not be readily available. This causes a further issue; the limited number of available large-scale data sets are then used by multiple AI statistical models—which limits the “learning” capability of any given technology, along with issues around how generalizable such a model may be across domains.

A similar issue is that of “black box” algorithms (so called because the data goes in and an answer comes out, but we don’t know what happens in the middle) and the wider ethical and usability concerns of such models. Many data-oriented AI models utilize tools such as neural networks, which can be difficult to interpret and understand, especially for the typical lay sports scientists. If we’re unable to fully understand how learning models make their predictions, we can’t fully assess—at least not accurately—the outputs of such models.

The models also become highly prone to bias. This happens because data points can be labeled as predictive in such statistical models but may be non-causal in nature—the model then uses this data type to make predictions, becoming biased in the process. There are many examples of this, and interested readers should check out Cathy O’Neil’s excellent book Weapons of Math Destruction.

A real-world example of this is AI used within the justice system that uses race as a causal factor, leading the AI model to become biased against people of color. More benignly, an AI model trained to differentiate between wolves and dogs in photographs did so based on the color of the background; if the background was white (i.e., snow), the model labeled the animal a wolf. This is because most of the photographs of wolves it was trained on were taken in snowy environments; however, when the model was shown a photograph of a wolf with a non-snowy background, it labeled the wolf incorrectly as a dog. This issue can be further compounded when AI algorithms are proprietary, making a full and accurate assessment of their validity and bias challenging. These problems are not unique to elite sport and relate to the broader Explainable AI movement.

Other issues affecting the uptake of AI in elite sport include overall usability and cost. On the first issue, the key question for us to ask is, “Does AI technology actually provide useful outcomes in an efficient manner?” As an example, computer vision technology struggles if the focus of the image (e.g., a player or athlete) is obstructed in some way. This means that in busy competition situations—such as a soccer match with 22 players on the pitch—a large volume of data may become lost and unable to be analyzed. Even a relatively simple task, such as identifying the numbers on player’s kits (used for post-match analysis), could end up becoming so corrupted that it is essentially useless.

In sports where total spend is highly regulated—like in F1—the cost of AI technologies may limit their effective use, says @craig100m. Share on XWhile cost is not typically an issue for elite teams in financially attractive sports (e.g., soccer, American football), it becomes an increasingly large issue for sports with smaller economies of scale (e.g., individual sports) and those from less economically developed nations. This, in turn, widens the gap between the haves and have-nots, skewing the playing field. In sports where total spend is highly regulated—like in F1—the cost of AI technologies may limit their effective use. This creates a further issue if organizations scrimp on the cost of adequate storage and security for the data they collect, creating further ethical challenges.

In their review article, Hammes and colleagues identify a further five key challenges around the use of AI in elite sport:

- Challenges in data collection (e.g., is the data fed into the models both valid and reliable?)

- Transferability of general AI research into the field of elite sport (e.g., how does new AI knowledge and technology become integrated into a relatively niche area?)

- An overall discomfort with machines “making” decisions—especially important ones (e.g., how do we use the data from machine learning and other models in the correct context?)

- Explainability of results (e.g., how do we explain the process used by the AI in coming up with the output?)

- The robustness of predictive models (e.g., can we move away from the current ability of AI to explain what happens to actually predicting it—and what is an acceptable error rate?).

Finally, there is a well-founded and genuine concern about an over-reliance on data and technology in elite sport. These concerns are typically based on the following:

- A blanket utilization of new technology without consideration of the performance outcomes.

- An over-reliance on data at the expense of context and practitioner expertise.

- An inability to capture all relevant information harming the ability to make fully informed decisions.

Where Does This Leave Us?

It’s clear that the use of AI in elite sport has huge potential, with the technology having the ability to both increase the depth of information collected and make this information useful to assist in decision-making. However, as outlined in this article, several key hurdles—scientific, ethical, and practical—need to be overcome before AI can be fully integrated, with utility, into elite sport contexts. These include issues around reliability and validity with both hardware and software and ethical issues around data storage and the use of black-box algorithms.

AI technology has the ability to both increase the depth of information collected and make this information useful to assist in decision-making, says @craig100m. Share on XFinally, the technology is currently quite costly (in terms of both purchase price and having staffing expertise to utilize it) and not currently able to live up to its potential (due to issues with, for example, video capture if part of the image is obscured). However, if—and likely when—these issues can be improved on, the potential use of AI in elite sport is large, as are the potential performance improvements, making it a worthwhile area for future exploration within elite sport.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF