The evolution of sports has led to a dynamic intensification of game speed, which has resulted in a rise in collision velocity. Game play, as well as the amount of force athletes can produce, is constantly increasing. As records are being broken across sports today, in-game player tracking is becoming more openly presented to the fan base. This increase in velocity can also be seen through the rise in force production that we witness daily on the field and in the weight room.

This change in sport, coupled with the turbulent times, makes return-to-play timelines, fatigue monitoring, game load monitoring, and overall analysis of physiological qualities more vital than ever. For this reason, it is essential that the high performance, sports science, strength and conditioning, and medical departments all work in a harmonious state.

As coaches, we always strive to provide justification or empirical evidence behind the methodologies we implement with our athletes. As part of the natural maturation process of being in the performance field, we continuously search for tools to help our athletes progress. Tensiomyography (TMG) is an incredibly powerful tool that provides real-time insights into muscle contractile properties (MCP), delivering quantitative data that fluidly transfers from the rehabilitation paradigm to the performance and game-play paradigm.

In fact, by implementing regular TMG testing, specialized rehabilitation methods may also be applied in microdoses as a complementary means to address the contractile properties of the damaged or injured muscles during standard rehabilitation processes. Even more so, these methods or applications can be seamlessly inserted into the performance model the athlete will enter once they have been cleared. Doing this makes the transition from rehabilitation to return to play that much more seamless, efficient, and individualized for the athlete.

TMG gives us the ability to not only hit the target but pick the exact point on the target that we need to identify finite fluctuations in muscle quality, says @DeRickOConnell. Share on XWith TMG, we are not simply throwing blunt-tip carnival darts at a balloon board, hoping to win the prize of identifying an issue. We are equipped with a Raven crossbow, precisely dialed in tight at 110 yards with ideal wind conditions and the perfect dew point, arming us with the ability to precisely home in on the underlying mechanisms causing the issue from a muscular perspective. TMG gives us the ability to not only hit the target but pick the exact point on the target that we need to identify finite fluctuations in muscle quality.

What Exactly Is Tensiomyography?

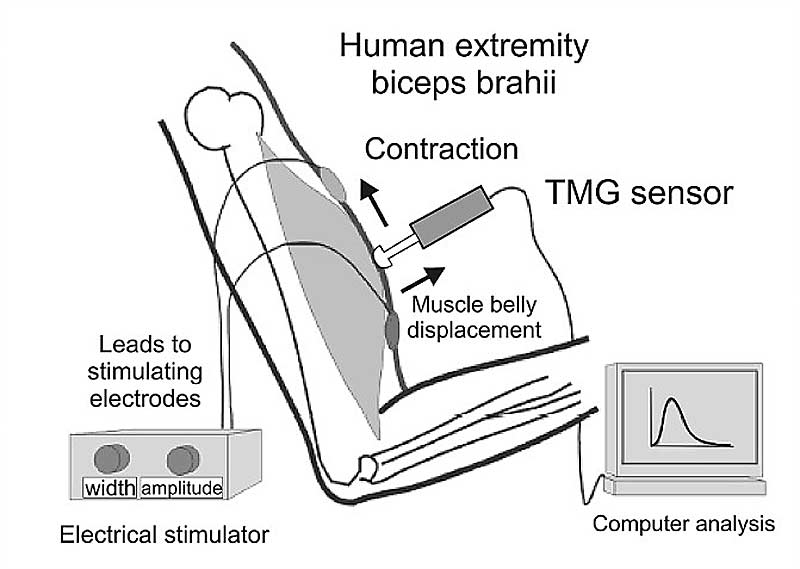

Tensiomyography is a powerful diagnostics tool that assesses muscle contractile properties by monitoring radial muscle belly displacement during electrical stimulus while under isometric conditions (as seen in the image below). This means that the system helps take the brain and nervous system out of the equation by manually firing the muscle and assessing the true qualities of the tissues without external stresses, demands, or influence from surrounding connective tissues. The contraction is initiated by the impulse stemming from the stimulator. From here, there is an instantaneously registered measurement and data collection on five specific MCP parameters, providing highly accurate, efficient, and quantitative results.

The Evolution of TMG in High Performance

Dating back to the 17th century, a small number of scientists could hear the sound of muscle contraction at very low frequencies. In 1810, William Wollaston was the first to link muscle sound with muscle force and thereby declare that muscle sound is at about 14–36 Hz, which was later proved as true (Oster, 1984). This was the beginning of mechanomyography (MMG), the oldest method of identifying muscle contraction properties. Later, as intrigue grew and concepts evolved, more intricate forms of MMG were developed, including utilizing lasers, accelerometers, and microphones. From there, the field evolved, and tensiomyography was born.

Tensiomyography is a noninvasive muscular analysis method invented by Vojko Valenčič at a Slovenian university in the late 1980s. Originally, TMG was designed for use in the medical field for degenerative muscle research. However, due in part to its fast and reliable muscular contractile properties, Srdjan Djordjevič and others’ work with TMG pushed its use to the forefront of the high-performance industry. By the mid-1990s, the high-performance and medical departments in sports were using TMG.

Before TMG was invented, there was no way to measure and collect finite individualized quantitative data on the specific muscle’s mechanical response, says @DeRickOConnell. Share on XBefore TMG was invented, there was no way to measure and collect finite individualized quantitative data on a specific muscle’s mechanical response. The data that TMG provides presents an in-depth understanding of the individual athlete’s specific muscle contractile properties (MCP) and a population reference. TMG enables us to analyze the intrinsic underlying elements of MCP, such as relaxation time, contraction time, and synchronization patterns. These MCPs can help us identify muscle fiber type, firing characteristics, and tonus qualities. The article “Tensiomyography Derived Parameters Reflect Skeletal Muscle Architectural Adaptations Following 6-Weeks of Lower Body Resistance Training” gives us an introspective look at using TMG for muscle fiber typing:

-

“Tensiomyography assesses contractile properties of an isolated muscle by measuring a number of parameters in response to a twitch contraction (Valenčič and Knez, 1997). Such parameters, including contraction time (Tc) and radial muscle belly displacement (Dm), can be obtained quickly and with minimal input from the participant being assessed. Tc has been previously correlated with proportions of slow twitch fibers within lower limb muscles, providing construct validation for TMG (Valencic et al., 2001; Dahmane et al., 2006; Šimunic et al., 2011); whilst a shorter Tc being considered reflective of a greater rate of force production (Rusu et al., 2013). Within the literature, Dm is considered to reflect muscle belly stiffness (Whitehead et al., 2001) and has been shown to alter with changes in muscle fatigue and aging (Rusu et al., 2013; Macgregor et al., 2016). TMG can distinguish between muscles of different training status, with shorter Tc and smaller Dm being seen in athletes with greater exposure to strength and power training (Loturco et al., 2015; De Paula Simola et al., 2016; Šimunič et al., 2018); due to increased proportions of fast twitch muscle fibers, and greater amounts of contractile material, respectively. Additionally, atrophy induced changes in muscle architecture are associated with increased Dm (Pišot et al., 2008; Šimunič et al., 2019).”

Next Step? Digging Into the Insights That TMG Provides

Utilizing TMG can lead to a large list of benefits for both the medical and performance departments. The tissue profile provided through TMG testing, widely used across European soccer leagues, enables the medical and performance departments to capture data that standard muscle testing and movement screening simply cannot encapsulate. This, in turn, provides training avenues otherwise typically unavailable.

TMG can be utilized to collect instantaneous quantitative data on the muscle’s contractile properties, and the reports created from this data can be used right there at the moment to change rehabilitation approaches and monitor real-time progress within the muscle. The ability to access this data so quickly and efficiently can aid in accelerating the rehabilitation process. This may also be an avenue to explore when determining what rehabilitation methods can be applied to the specific athlete after they have completed the rehabilitation continuum with the medical staff.

Specialized rehabilitation methods can be applied in microdoses as a complementary means to address contractile properties of the damaged or injured muscles while the athlete simultaneously completes their required performance training. Data consists of five distinct muscle contractile properties that are inherently connected in the proper functioning of the muscle. These parameters are:

- Delay time

- Contraction time

- Sustained time

- Relaxation time

- Displacement

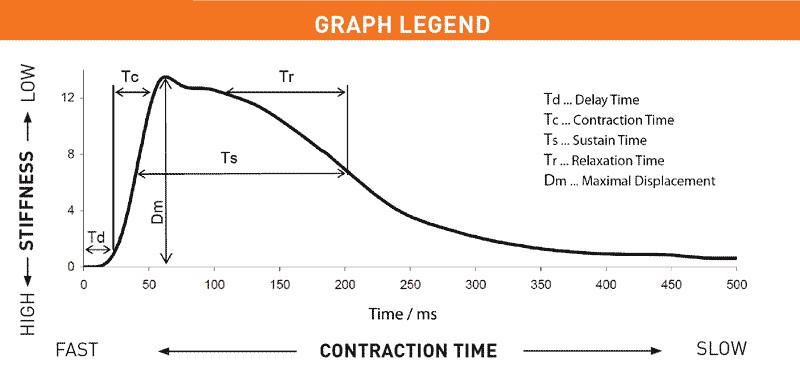

1. Delay Time (Td)

Delay time is a measure of the initiation time it takes for the muscle to be fired once stimulated. TMG presents this data of the time between the electrical impulse and 10% of the contraction. From a very basic perspective, this measures how long the muscle takes to contract from total relaxation to contraction once an impulse is sent.

2. Contraction Time (Tc)

Contraction time is a measure of the duration of time that it takes for the muscle to contract fully. To decrease variance, TMG collects data in a window of 10% and 90% of the stimulated contraction.

3. Sustain Time (Ts)

Sustain time is a measure of the duration of the muscle’s contraction from the mid-point to the end of the relaxation cycle. This is represented within the data as the time between 50% contraction and 50% relaxation. Simply put, this measures how long the contraction is sustained or held.

4. Relaxation Time (Tr)

Relaxation time is a measure of how long it takes the muscle to relax. An athlete’s ability to relax is imperative in performance. This measure is represented in the data as the time between 90% and 50% of the relaxation, as discussed in Supertraining, and part of the rationale behind the importance of training with ASFM (especially oscillatory methods). The greatest differentiator in elite-level performance does not lie in the athlete’s ability to contract an agonist muscle but in their ability to relax their antagonist muscle. This ability leads to more efficient and purely powerful movements.

5. Displacement (Dm)

Displacement is the measurement of the distance that the muscle covers when it contracts—the “flex” of the muscle (otherwise known as the maximal displacement of the muscle belly). This measure closely relates to the tonus or stiffness of the muscle.

Below you will find a key from the TMG website on how to interpret the information in the graph based on the five elements of MCP that were analyzed during the assessment.

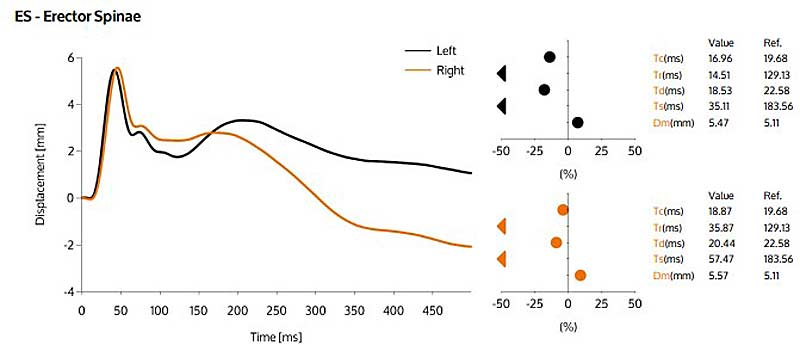

Once a test is completed, the software creates a graph of the contraction separated left versus right. Below is a sample reading I took of an athlete, examining their erector spinae via the TMG software. The graph also includes specific population-based averages such as sport and position within the sport to compare live assessments to (shown to the right, marked “Ref”).

The graph above represents a particular measurement within a much larger report (via the TMG software). Several auto-created reports in that dashboard can be selected, including individual reports and team report analyses. The information presented in these reports includes:

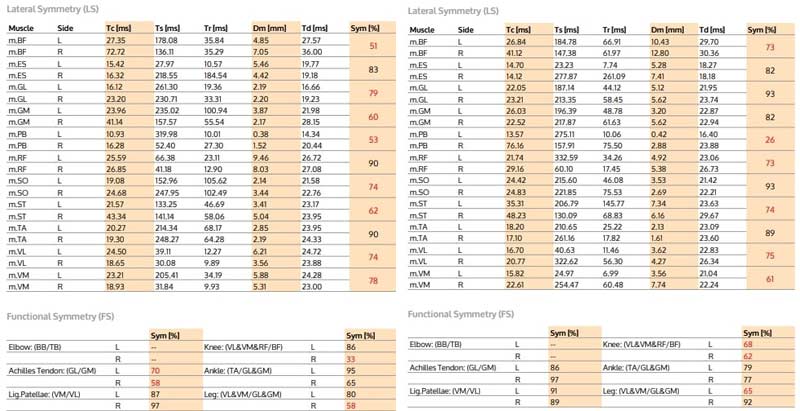

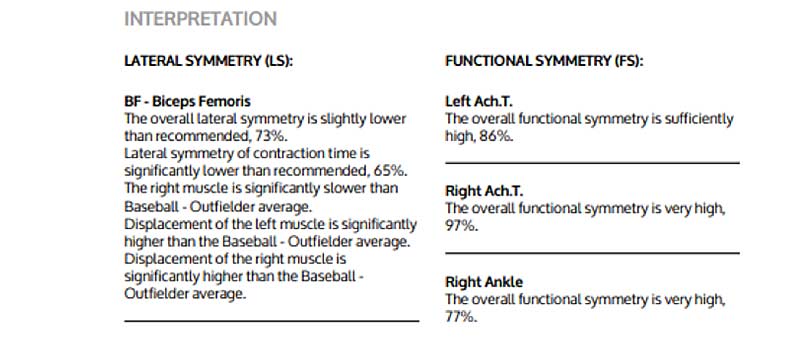

- Data highlighting lateral and functional symmetries.

I have included images of this data below to help give a better idea of how the information is initially presented. These are the comparative test results during a two-week phase of rehabilitation. The first image is where the athlete entered the rehabilitation process; the second image represents the results after spending two weeks on an altered plan based on some of the data provided by TMG. While it is clear that this athlete still has a long road ahead in the rehabilitation process, we can see significant progress in finite areas that I could not quantitatively represent before I assessed the athlete. We can see that exceptional progress has been made, especially within the functional symmetry of the Achilles tendon.

- Line graph representation of MCP (seen above).

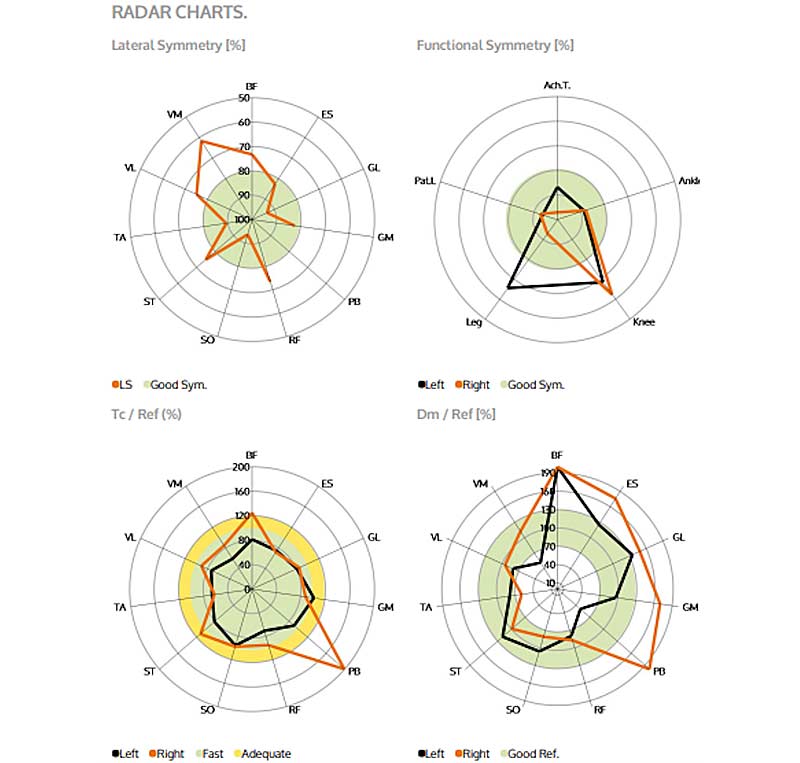

- Radar chart indexing comparative standardized value ranges (seen below).

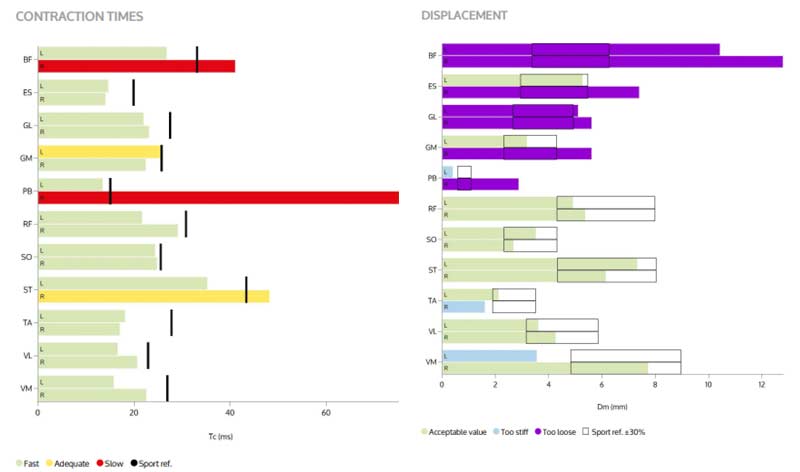

- Bar graphs on displacement and contraction windows—sports reference, acceptable value, muscle stiffness, etc. (seen below).

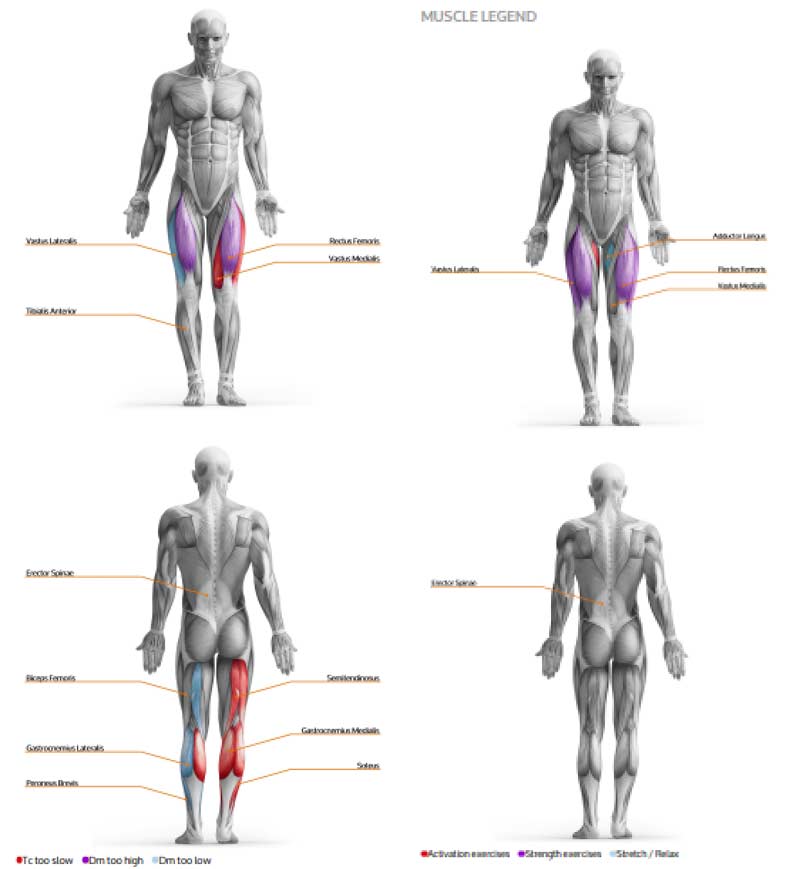

- A color-based chart overlaying a graphic of the human body highlighting worrisome contractile readings and possible inventions to address these issues (seen below).

- A simplistic paragraph interpreting readings and possible interventions (ex: strengthening, stretching, activation, and relaxation techniques) on the left versus right side, highlighting functional and lateral symmetry in comparison to the player population. Below you will find a tiny snippet of what this part of the generated reports looks like.

Taking the Next Step with the Data

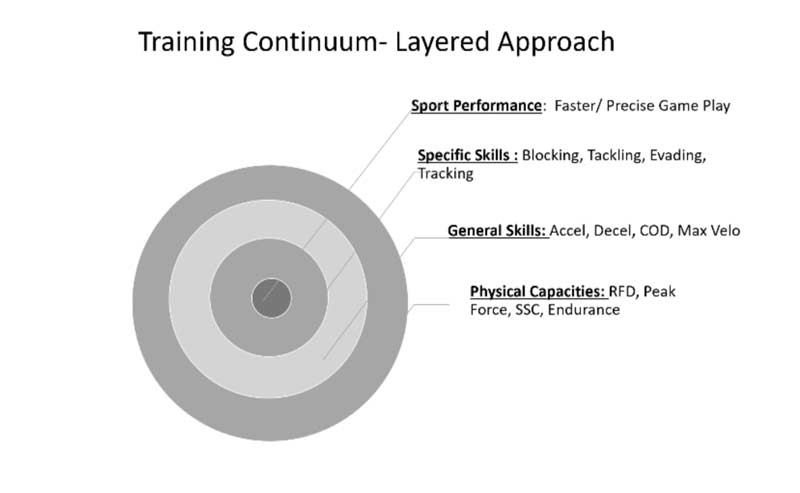

While the TMG software provides a great starting point for remedying the MCP deficiencies each athlete possesses, if we begin to dig deeper and think about connecting the data to the demands of the sport, we can identify ways to address specific qualities with manipulating exercise techniques.

If we dig deeper and think about connecting the TMG data to the sport’s demands, we can identify ways to address specific qualities with manipulating exercise techniques, says @DeRickOConnell. Share on XThis approach allows us to apply specific techniques to each athlete to address individual inefficiencies or rehabilitative needs as they concurrently complete their scheduled training phase with the team. TMG enables us to provide the athlete and high-performance team with real-time data during the rehabilitation process. We can perform testing weekly or bi-weekly on all surrounding muscular groups to identify any increases in the contractual qualities of the injured muscle, as well as all musculature surrounding the joint or up the chain.

This is especially useful for athletes who have been in a cast or sling and may have lost a considerable amount of musculature or the ability to actively contract and recruit the muscles that are involved around the injured joint. A situation such as this typically leads to poor movement patterns and downregulation, as synchronization abilities are inhibited due to the injury.

One of the most interesting cases I have encountered was an athlete with repetitive ankle injuries. The biggest issue, however, was that it was challenging to assess progress within the rehabilitative process due to the nature of the injury. The athlete could not perform any loaded movements, and passive range of motion assessments did not paint a large enough picture. Furthermore, since structural strength was nearly diminished and inflammation was high due to the recovery process, strength testing was not going to be feasible either. TMG enabled us to identify and track progress around the ankle, deep in the foot, and up the lower body’s kinetic chain.

By approaching the injury in this manner, we were able to identify factors that we typically are unable to assess and then provide quantitative data on the affected area of injury.

From this information, high-performance departments can analyze synchronization symmetry within the athlete and even begin to standardize their own sport- or position-specific protocols. For example, a quick and simple “Hockey Assessment” that I created provides quantitative data of MCP and synchronization patterns within a hockey population, which includes running TMG testing of:

- Biceps Femoris

- VMO

- Erector Spinae

- Adductor Longus

- Rectus Femoris

- Vastus Lateralis

- Semitendinosus

I perform this test as an entry-level diagnostic for all hockey players entering off-season training. Dovetailing off this assessment, TMG provides two incredibly insightful measures of synchronization patterns:

- Lateral symmetry

- Functional symmetry

These measures are an outcome of a formulated analysis looking at all five MCP properties measured via TMG. Lateral symmetry provides insight into the MCP elements of a muscle via left versus right (for example, looking solely at the data of the left VMO to the right VMO). These measures are provided for the individual but also compared to the population of the sport. We can use this data to create systemic red flags when an athlete presents outside of a certain window of symmetry.

It would be a good idea to create your own sport-specific data pool based on the population you are testing or use the sport reference data provided via TMG. This helps you to be aware of sport-specific synchronization adaptations that occur due to the movement demands of the sport. For the most part, a window of 10%–15% deviated asymmetry is commonly used as a “red flag”—if this type of marker is presented, it may be time to discuss the results with the medical department and build out a plan to address the issue.

Functional symmetry is also provided through the data that TMG records during the test. This is an incredibly valuable tool, and TMG provides an endless list of possibilities that allows us to identify asymmetries across joints throughout the entire body. This measure is even more important in determining possible injury potential. A typical window used in identifying injury risk is a functional asymmetry rate of 30%–35%. If an athlete presents outside of this, they will likely be exposed to higher injury risks during game play. You can use the provided functional symmetry readings to catalog and monitor athletes or create your own data monitoring system and import the data of tests you make, such as the above hockey test. As an example, functional symmetry TMG provides an equation for functional knee symmetry that is (VL&VM&RF/BF).

TMG provides an endless list of possibilities that allows us to identify asymmetries across joints throughout the entire body, says @DeRickOConnell. Share on XThe information provided here, along with the other tests the athlete performed, helped to illuminate any glaring needs in training as well as offer great general insight into the MCP of each athlete. This data can also be used to compare the specific individual’s contractile properties to an entire population of elite, college, and professional hockey players and forward versus defenseman, as well as female versus male.

What is great about TMG is that not only can you build out your own population pool and data representation, but TMG as a company has been collecting thousands of data points for years, providing a large population pool that allows you to compare athletes in just about every sport to previously collected assessments. This data collection is also continuously updated, ensuring a constant input of new comparative data within the system.

From Rehabilitation to Performance

As we touched on earlier, the information collected gives us insight into MCP synchronization patterns, fiber typing, and fiber dominance. However, we can go even further and assess real-time fatigue and potentiation rates.

I have been fortunate enough to thoroughly explore and investigate the MCPs of athletes in a multitude of ways with TMG. The data represented could be used to identify peak potentiation times, helping to focus on specific exercise duration and the effects of different periods of eccentric, supramaximal eccentric, overcoming isometrics, loaded oscillations, and power range concentric exercises ranging in duration from 2 to 10 seconds. It could also help break down the differences in muscle response when an athlete performs these exercises in a single effort bout or a repetitive effort bout such as cluster sets.

We can take this a step further and not only assess potentiation rates by duration and exercise but also identify contractile response differentiation in specific muscles versus the movement. This, in turn, helps to illuminate the exact response a muscle gives based on specific exercises or movements. From here, we can use this information to begin to build out peak potentiation profiles. These profiles can be based on collected information such as sport (also investigating movement pattern dominances and synchronization adaptations of the sport), gender, the potentiating exercise, the duration of exercise, and the muscle groups involved to help create performance training cycles that flow together.

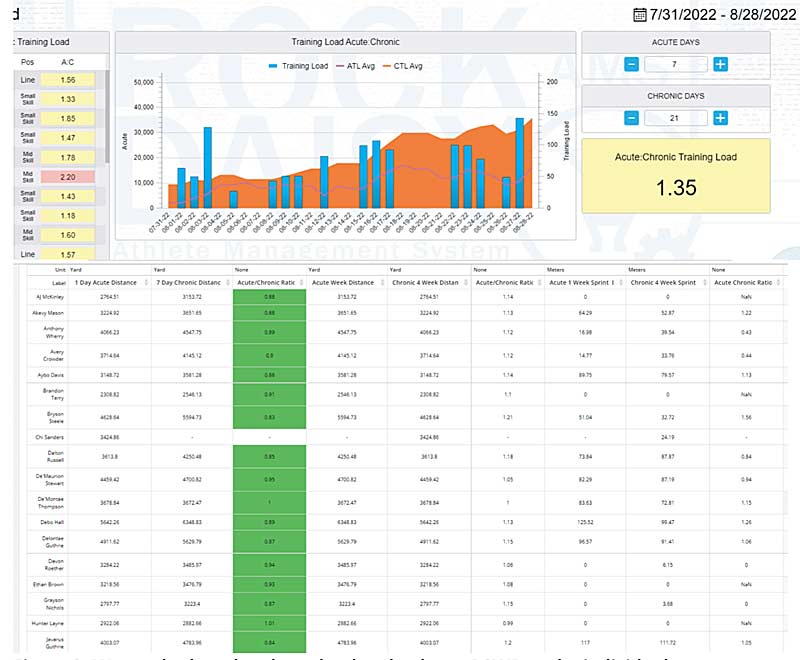

MCP fatigue can be monitored throughout the season, not just from a training perspective but also as a means of diagnosing potentiation and exertion fatigue rates. We can insert the data provided into our athlete monitoring systems as part of the workload management equation. Decreases in positive MCP may signify a need for alterations to training plans and practice loads and even signal oncoming illness. This data gives us an opportunity to diagnose not only instantaneous and acute fatigue but also chronic fatigue, identifying and adjusting days ahead of a potential injury, poor performance, or possible overtraining syndrome.

For additional information on implementing TMG readings as a means of monitoring potentiation fatigue rates, I highly suggest watching the presentation by Srdjan Djordjevic. His course on the “Development of Speed” is a great resource on the various ways to apply TMG to quantify the influences of potentiation and identify fatigue rates.

As an additional note, below is an excerpt from an article by Carl Valle that perfectly encapsulates what TMG can mean to a high-performance department:

-

“Coaches care about managing fatigue, and medical professionals tend to want to know about the risk for a new injury and the recovery for existing injuries. Screening has always been murky, but sometimes an athlete still struggles with a lingering problem that is a ticking time bomb. Athletes can pass movement screens and range of motion tests and still have a neuromuscular impairment.

Tensiomyography is the equivalent of a lie detector for muscles. Athletes often know when something is wrong and while medical professionals may listen to their complaints, TMG connects the subjective information to something tangible for the professional. Since the information is objective and quantified, it’s a permanent record of how the tissues trend over a season.”

Quantifying Systemic Effects of Various Interventions

Another avenue that can be explored is using TMG to identify changes in MCP before and after soft tissue therapy, neurolymphatic work, neurological wake-up drills, various breathing modalities, and acupuncture. By doing so, we can see what is truly happening to MCP before and after these processes. Of course, there is a larger window of variance over the population as a whole when looking at these types of interventions for several reasons. Still, it is nevertheless very interesting to see how an individual’s tissue responds.

The TMG website also provides an extensive list of scientific publications that I highly suggest reviewing. The database of research articles covers all topics from a medical perspective to a high-performance perspective. The link to this page can be found here: Tensiomyography; Full List of Publications.

TMG and the Hyperspeed Exercise Continuum

How can we use TMG readings to help identify what modality within the hyperspeed exercise continuum may be applied to the athlete to help make their training even more specific?

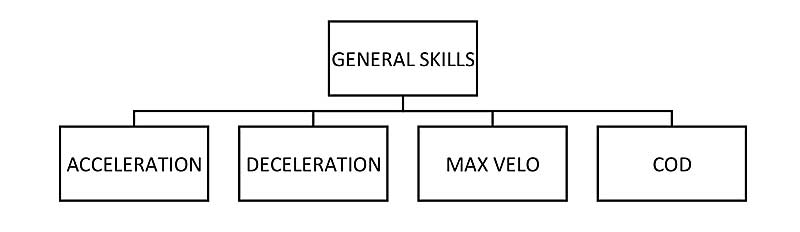

Before we get into how the methods fit in with different TMG variables, I wanted to give a brief overview of each hyperspeed modality. Through standard training methods, it is incredibly difficult—if not impossible—to train with or expose an athlete to the velocity demands that they will see on the field of play. It is crucial that we try to find ways to help athletes adapt to these demands in their training. This is not only vital from an athletic enhancement perspective but also paramount from an injury prevention perspective and the return to play transition.

We want to help the athlete’s kinetic chain be able to produce and withstand high-velocity force. Even more importantly, we want the athlete to be able to possess a high work capacity within these means. I know at first glance it may seem counterintuitive to say that work capacity and peak velocity movement coincide, as we typically train the qualities separately, but in the field of play, while velocities may diminish due to fatigue, an athlete faces the demand to perform at their peak velocity for the duration of the game or match.

Along with this come repetitive bouts of max-effort, high-velocity movements. Many athletes experience injuries when they are fatigued and as their game workload increases—this is especially apparent in athletes who are returning to play after an injury. If not adequately prepared from a training as well as a workload re-integration perspective, these athletes are at high risk for reinjury and, unfortunately, multiple reinjuries.

Hyperspeed exercises attempt to capture and train an athlete in an extremely high velocity-force perspective by applying various methods to address co-contraction, elasticity, and neural work capacity. These may be the three most important methods to apply in training athletes for high performance and return to play.

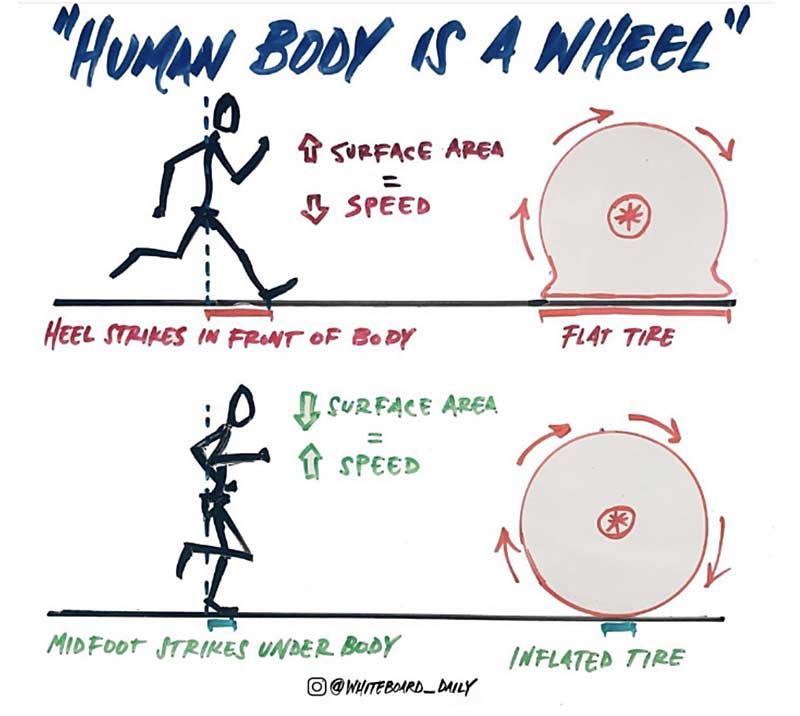

Co-contraction, elasticity, and neural work capacity may be the three most important methods to apply in training athletes for high performance and return to play, says @DeRickOConnell. Share on XThe concept of co-contraction refers to the body’s—specifically, the nervous system’s—ability to create perfect synchronization of opposing muscles around a joint to stabilize the structure. This correlates to sprinting in that as the foot strikes the ground, muscles need to quickly activate in unison to create rigidity and stiffness in the joint to meet the force and power demands of the movement. To make it easier to understand, visualize or even watch a video of a cheetah sprinting at full speed: as the animal goes from a dead stop into a full sprint, hitting speeds over 60 mph in under three seconds, its dorsal line, the line from behind the skull extending into the tail, maintains the same postural positioning and triggers signals to the brain to maintain an intensified visual focus.

Of course, sprinters and athletes clearly do not have the same physiological composition as a cheetah; however, we can train our nervous system to elicit this characteristic. As the cat accelerates, all four of its feet strike completely different ground surfaces and levels simultaneously. The cheetah uses a highly adaptive co-contraction trait to stabilize its joints and continue to accelerate through the unpredictability of surface terrain. This is co-contraction in its most prime example and the response that we want to elicit through training.

To function correctly, the demands must be met at an even quicker rate than the velocity being created in the limbs and body during sprinting. Sometimes, a lack of rigidity can downregulate the output of power if the brain feels there is an unequal ratio of stiffness to power. Too often, developing co-contractions is overlooked and not conceptualized or held to the proper level of importance. Programs often place too much emphasis on standard strength training practices, focusing on progressively loading an athlete in a rep range to become stronger. While strength and power are obviously very important aspects, it is crucial from a performance standpoint that the principle of co-contraction and time be considered and applied in training.

Athletes must be able to withstand high amounts of eccentric force. This means the athlete should not simply “absorb” force but withstand and propel it under the applied tension, creating an extremely rigid movement and increasing rate of force development. An athlete will only become as powerful as the eccentric force they can withstand. This takes precedence over other qualities when it comes to true elite-level performance.

When loading an athlete, there is very little co-contraction needed to push a barbell with both feet planted on the ground; however, this is not the nature of sport (except for powerlifting). When moving at high velocity, co-contractions occur in a hundredth of a second. As the nature of the sport demands high-velocity movement, the body needs to elicit these co-contractions at an even more efficient rate. Keep in mind that co-contractions dictate many aspects of movement, most notably the ability to create explosive movement and reduce injury during these demands. For the purpose of this article, we want to develop and prevent both.

Co-contractions are also part of the stumble reflex. When someone falls or trips, the body tightens up to prepare for that fall. This occurs so you do not get hurt or fall to the ground. This primitive reflex is why your body syncs up when you trip on something, and the next step is very stiff.

To elicit and train this, we want to trick the body into thinking we are going to trip. This approach will develop greater pre-tension when we hit the ground. The more pre-tension an athlete possesses before hitting the ground, the stiffer the joint will be, and the less energy is displaced and wasted when the athlete goes to push during their next step. You can find more in-depth information on the importance of co-contractions and how they apply to sprint training in “Triphasic Speed Training Manual for Elite Performance: Part 1 The Spring Ankle Model,” which I wrote along with Cal Dietz and Chris Korfist.

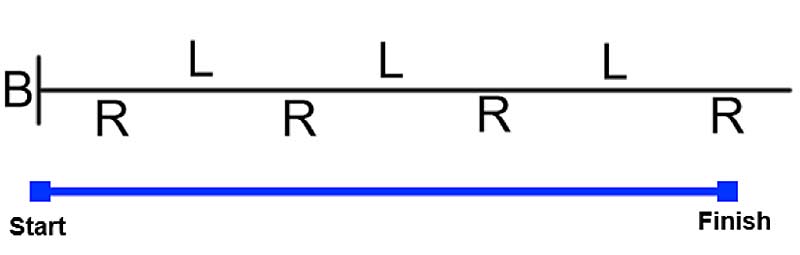

1. The Co-Contraction Method

Implement this method by placing bands above and below the working limb or limbs. There is typically slightly more band tension placed on the side of the targeted muscle/muscle groups. This method aims to create a significant adaptation in synaptic signaling rates, which will, in turn, create a higher transmission speed between neurons. As the athlete begins to adapt, they will start creating incredibly fast neuromuscular actions around the joint. This includes quicker rates of turning the muscle on and off, as well as increasing dynamic stabilization around the joint that adapts to meet the need of the velocity created by the limb.

The outcome of this method is a significant gain in neural adaptations throughout the body. Of the three primary methods, co-contraction is performed with the most ferocious intent at the highest velocity. This method is most commonly implemented in speed, peaking, and concentric phases. Athletes who exhibit an increased need to improve coordination and agility may also see large benefits from performing this method. Depending on the desired adaptation and the athlete’s training level, external loads such as small dumbbells and ankle weights may be applied to the exercise to increase demand.

Video 1. An upper body co-contraction method exercise: Prone Incline Rear Delt.

Video 2. A lower body co-contraction method exercise: Hip Abduction/Adduction Contralateral Narrow Stance.

From a TMG perspective, if a muscle exhibits low neural drive symbolized by slow contraction time, implementing co-contraction methods may lead to the greatest gains for that athlete. This method tends to be incredibly taxing on the central nervous system. Band tension is commonly overlooked; however, it is very important that adequate band tension is placed on the athlete. Without this, the exercise’s speed will greatly diminish, reducing contraction times and requiring increased and unnecessary stabilization time and energy.

2. The Rebound Method

I often describe this method to younger athletes as “the kangaroo exercise,” which helps them picture the movement’s demands. The exercise is performed with large, graceful bounds led by band contact filled with ferocity and aggressiveness. This method requires a violent movement against the bands, creating a massive demand in eccentric braking forces to decelerate the movement and leading to adaptation in the athlete’s tissue (very similar to the contraction requirements of a bound). We can think of this as a juiced-up shock method exercise, especially when performed with a pause.

With the rebound method, we can produce plyometric-like movements in all planes, with upper- and lower-body extremities. The rebound method is very commonly placed with the eccentric, strength, and power phases of training. Alterations to the methods can include placing dumbbells in the hand or ankle weights on the athlete. Remember, adding this external weight and changing band tension alters contractile properties. This modification in load and velocity moves performance qualities from an eccentric emphasis to a strength or power emphasis, depending on the velocity and contraction demands of the movement. Implementing rebound methods for the muscle group may lead to the most significant improvements for an athlete who exhibits deficiencies in maximal displacement.

Video 3. An upper body rebound method exercise with external weight: Bent Over Rear Delt Rebound.

Here are some examples of lower-body rebound method exercises:

Video 4. Standing Angled Hip Flexor Rebounds.

Video 5. Hamstring Razor Curl Double Band Rebound.

Video 6. Hamstring Razor Curl 3 Band Rebound.

Here is an example of a lower-body rebound method exercise with external weight:

Video 7. Ankle Weight Prone Psoas Rebounds.

3. Oscillatory Isometrics (OCIs)

OCIs are often used when metabolic and high-velocity work capacity demands are the target of adaptation. From a metabolic perspective, OCIs are by far the most demanding technique: the method is performed by placing the limb against a band and performing an oscillation into the band. The most important exercise element is ensuring the athlete maintains constant tension without leaving the band. The general movement can be small, but due to the application of constant tension and recruitment demands, this variation is very taxing on the metabolic system.

Typically, this method is worked into early phases and return to play scenarios, where work capacity and tissue adaptation are the primary focus. However, the adaptations involved in the movement also slide very well into power phases. OCI also syncs well with quasi-isometric training; for example, if an athlete exhibits significant deficiencies in sustaining times as measured by the TMG, OCIs may be a great tool to introduce to the athletes’ training regimen.

Video 8. A lower body OCI: Prone Psoas OCI.

Options for Application

Now that we have collected the data, we have a couple of different ways in which we could approach each athlete. Looking at one hypothetical example, let’s say we have an athlete who is cleared to move out of general preparation and into a heavy eccentric phase. This athlete, however, is also currently dealing with a lingering shoulder injury from the season. While the athlete is likely scheduled to perform the rebound method with light dumbbells and ankle weights throughout this phase, we can use the data to address the MCP demands that are present in the shoulder as well. Coming off a long-term shoulder injury in which the athlete has spent time in a sling greatly affects the amplitude and, even more likely, the displacement. From here, we have a couple of viable options for the athlete.

- If we deem that OCIs are the best route to take to target the athlete’s shoulder issues, then we could have the athlete perform their prescribed rebounds throughout the phase and simply replace rebounds with OCIs, being sure to sync up the duration of the exercise so that the global stress remains constant. TMG allows us to combine a typical global hyperspeed approach while implementing an individualized local stimulus approach when necessary.

- Another option is to address imbalances by implementing hyperspeed modalities that meet the specific demands microdosed throughout the week or by taking a grand-scale one-day macrodose approach. For example, this is where you could keep the aforementioned athlete on weighted rebounds throughout the week and then simply switch the entire approach at the end of the week, when volume typically takes precedence. The athlete would then perform only OCIs for the entire workout, focusing on every joint and not just the shoulder.

Using the data presented via TMG may also allow us to manipulate in-season phases. Constant monitoring enables us to combine the athlete’s needs with the modality that may help them the most. In doing so, we distribute exercise protocols that allow the athlete to improve at a personal level and also preserve vital in-season energy stores. We may split our teams up into groups that need to focus on a rebound day, a co-contraction day, or an OCI day. As discussed above, we may also have the opportunity to blend a primary modality with just one or two of the others that match the specific contraction demands of an athlete.

In another scenario, the athlete might perform a rebound day without added external load but added co-contraction for the hamstrings, as the athlete possesses slow contraction rates and plays a high-velocity sport. In this case, stimming or potentiating at a low volume may be beneficial for the given athlete.

Given the data we are presented with, there are endless possibilities for making minor adjustments that can create huge benefits for each athlete individually. Applying hyperspeed modalities to sync with the current goals of the phase is very common, but now we can sprinkle in very specific modes for various athletes who may be coming off injury and rehab protocols or athletes who simply need to remain in a very specific and individualized phase.

Bringing Together Tensiomyography and Hyperspeed Exercises

Below, I have created a starting point for correlating TMG readings and applying hyperspeed exercises. This is meant to be a jumping-off point, primarily identifying one or two elements of each measured parameter. I wanted to begin the conversation here, as it’s meant to inspire a much deeper look into the various correlations that exist when addressing these qualities in a precise manner. However, even by looking at a particular element of each measurement, we can begin to implement a plethora of changes to each of our athlete’s programs as we are likely to see at least one of these deficiencies pop up in each athlete’s test.

Let’s look at each of the elements analyzed through testing, as well as one or two hyperspeed exercise adaptations that can be made based on the data presented:

Delay Time (Td)

Delay time is heavily associated with an athlete’s nervous system firing rates. If an athlete exhibits a delay time that exceeds the normative values based on the population reference, they may possess a below-average neural synaptic transmission or “slow neural drive.” One possible way to combat this is to introduce the athlete to co-contraction exercises.

Another often-seen cause for excessively high delay times is fatigue. This could be caused by sport, overtraining, or low work capacity. If we rule out all external causes, and it is genuinely low work capacity or muscular endurance issues, ICOs can be inserted into the athlete’s program to address this issue.

Contraction Time (Tc)

If athletes exhibit a sluggish time to contraction, they may need to find ways to improve firing rates. This can be done by incorporating co-contraction exercises throughout their programming. By doing this, we are attempting to increase the muscle’s response to instantaneously high velocity switches between agonist and antagonist muscles.

Often closely associated with muscle composition, another avenue that can be explored when an athlete exhibits slow contraction times are activation exercises. We can explore two routes to identify which the athlete is more responsive to:

- We can begin by having them perform a hierarchy of activation exercises for and around the muscle or muscles that exhibit the inhibition in contraction time.

- We can address the downregulation or inefficient firing patterns through methods such as Reflexive Performance Reset to help the nervous system fire in a way that allows the muscles to contract at a higher, more efficient rate and pattern, as there may be deeper reasoning behind the contraction inhibition exhibited by the athlete.

Sustain Time (Ts)

If an athlete exhibits an above-average sustained time (“above-average” being a negative correlation) compared to the reference data, this could be due to several factors. Above-average sustained time can lead down a very extensive list of possible correlations. For now, we’ll focus on forcing an on/off switch within the body, specifically the nervous system. In this case, we will apply co-contraction methods as a means to encourage that “off switch” development.

During the co-contraction, the body, of course, is forced to turn on very rapidly, but by doing this, the opposing musculature must also turn off. As a very important side note, I would also look into the athlete’s overall workload and trends, as they may be entering a window of extreme fatigue.

Relaxation Time (Tr)

Relaxation time, along with sustained time, has been discussed in close relationship with the functionality of the sarcoplasmic reticulum. More specifically, I am referring to the efficiency of the calcium pump. This pumping action is the incipient stage of a muscle contraction. These two measures offer a bird’s-eye view of the reciprocating actions needed within the sarcoplasmic reticulum for proper muscular contraction. Time to relaxation can be associated with several MCP qualities that may need to be addressed.

If an athlete exhibits prolonged relaxation time, this is typically a sign that the tissues are having trouble releasing tension. An avenue that can be explored with athletes who exhibit above-average relaxation time is to address the tonus within the tissue. Myofascial release modalities, ART, or stretching modalities may lead to improvements in the quality of the tissue. Examining this issue from a training perspective, there are two first steps that you can take with the athlete. The first is applying co-contraction methods to improve the athlete’s ability to turn on antagonist muscles, thus leading to a forced adaptation to relaxation.

However, rebound methods can be applied if the athlete is presenting a discrepancy in relaxation time coupled with above-average displacement. Finally, a critical component to consider is the athlete’s psycho-emotional balance. This type of athlete may be overtrained and experience chronic fatigue factors. They may also be in a state of chronic sympathetic dominance. In these cases, manipulating the hyperspeed exercise isn’t necessarily what the athlete needs. They may need a decrease in workload, soft tissue work, breath work, grounding work, and light and heat therapy, and overall increases in time spent focusing on relaxation. In some cases, this athlete may also need to alter their diet and supplement regimen to attain healthy gut microbiota.

Displacement (Dm)

Deficiencies in maximal displacement may signify several different possibilities. If an athlete exhibits higher than the reference point of displacement, this may signify that the muscle in question may lack absolute strength. From a performance perspective, this translates into the athlete being able to withstand and reciprocate force. If possible, you may want to compare this data with drop jumps on the force plate, RSI, or other testing procedures involving force absorption and breaking ratios. If the correlations do match, then applying the rebound method may lead to the most considerable improvements for the athlete.

Maximal displacement can also disturb relaxation time due to muscles still being under tension. This delayed relaxation effect is the culmination of mechanoreceptors being overloaded due to too high of a displacement. If you deem that the athlete is simply weak, untrained, or coming off an injury and also lacks general strength and muscular endurance, applying more OCI exercises may be the best option for the given scenario. Lastly, as displacement also provides excellent insight into the tonus qualities associated with the muscle, below-average displacement may also require stretching or other tissue and myofascial interventions to improve the general MCP qualities.

Correlations in Performance Assessment

There are now other qualities that researchers have begun to analyze based on these five primary measurements. From a structural and medical perspective, we can take a deep dive into the MCP qualities that each athlete possesses. Using these preexisting qualities, we can create our own customized profiles using the bilateral and functional symmetry formulas to monitor fatigue, track rehabilitation progress and address each muscle in a powerfully tailored and specific manner.

New research and published formulas have started to shed light on more specific MCP correlations and algorithms. From a performance perspective, we can combine all the above information with formulas that look directly at contractile velocities. Contraction velocity is a metric calculated using a comparison formula between Maximal Displacement and Contraction Time. This gives us a very interesting insight into an athlete’s contractile velocities. This can be incredibly useful in high-velocity-based sports and training, first as a general diagnostic and also as a way to monitor finite deviations in fatigue rates.

Contraction time (Tc) provides us with insight into the speed at which a muscle twitches and coincidingly contracts in relation to maximal displacement. However, one such parameter that is now being explored as a more specific means to monitor athletic performance is known as a velocity of contraction (Vc). Velocity of contraction is a calculated formula that represents the sum of maximal radial displacement divided by delay time plus contraction time:

-

𝑉𝑐 = Dm / Td + Tc

The idea is that by bringing together all of these assessment points within the muscle, we can get a better picture of velocity demands. TMG-derived velocity of contraction can be an incredibly valuable tool. By using this formula, we can simultaneously integrate the mechanical outcomes provided by TMG. Velocity of contraction is capable of detecting functional changes in the muscle’s mechanical properties, at least when these neuromechanical adaptations are related to the impairments in maximal sprint ability and COD speed performance in professional soccer players (Loturco et al., 2016).

TMG-derived velocity of contraction can be an incredibly valuable tool. By using this formula, we can simultaneously integrate the mechanical outcomes provided by TMG, says @DeRickOConnell. Share on XNormative values and a standardized formula for Vc are still being established. Vc can be used as part of the equation in fatigue monitoring; however, due to the elements involved in the formula, Vc is affected differently depending on the specific stress of the sport. For example, impaired Vc was delayed until 72 hours after completion of high-intensity endurance training, unlike high-intensity strength training, after which Vc was impaired immediately (Macgregor et al., 2018)

Research into Vc has also led to the attempt to standardize another formula to encapsulate overall athletic performance, including fatigue rates and even fiber typing. This metric is known as normalized response speed or radial twitch response (Vrn). Normalized response speed shows us the relationship between the difference of the deformation between 10% to 90% and the increase of the contraction time for those values (Rojas-Barrionuevo et al., 2017; Rodríguez-Ruiz et al., 2014). When a muscle becomes enhanced, it shows lower values in Dm, Ts, and Tr and a decrease in Tc. In contrast, a fatigued muscle (or due to a deficit of mass or muscle tone) presents higher values in Dm, Td, Ts, and Tr and an increase in Tc (Rojas-Barrionuevo et al., 2017). Additionally, Vrn is a relevant indicator of functional instability and influences jumping capacity (Rodríguez-Ruiz, et al., 2014).

By spending additional time interpreting the data from these measures, we can begin to tailor incredibly specific programming protocols for our athletes based on finite alterations and data. While there certainly is a large number of correlated possibilities when analyzing MCP with TMG, using the data to apply hyperspeed-specific modalities presents us with tools that are simply unattainable through other avenues of assessment.

This article aims to help change just a few elements in the initial programming based on the athlete’s needs. From here, we can begin to have an even deeper conversation about correlated applications. By providing one or two possibilities per contractile element, we have an incredible foundation of programming adaptations that can help us provide our athletes with very specific training variations—not to mention the vitality this data can give our high-performance departments when accelerated return to play timelines are in demand.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Detecting the velocity of the muscle contraction.

Loturco I, Pereira L, Kobal R, et al. “Muscle Contraction Velocity: A Suitable Approach to Analyze the Functional Adaptations in Elite Soccer Players.” Journal of Sports Science & Medicine. 2016 Sep.;15(3):483–491.

Macgregor LJ, Hunter AM, Orizio C, Fairweather MM, and Ditroilo M. “Assessment of Skeletal Muscle Contractile Properties by Radial Displacement: The Case for Tensiomyography.” Sports Medicine. 2018 Jul;48(7):1607–1620. doi: 10.1007/s40279-018-0912-6. PMID: 29605838; PMCID: PMC5999145.

Meglič A, Uršič M, Škorjanc A, Đorđević S, and Belušič G. “The Piezo-resistive MC Sensor is a Fast and Accurate Sensor for the Measurement of Mechanical Muscle Activity.” Sensors. 2019; 19(9):2108.

Oster, G. “Muscle Sounds.” Scientific American. 1984;250(3):108–115.

Rodriguez-Ruiz D, Diez-Vega I, Rodriguez-Matoso D, Fernandez-del-Valle M, Sagastume R, and Molina JJ. “Analysis of the Response Speed of Musculature of the Knee in Professional Male and Female Volleyball Players.” BioMed Research International. 2014. 8. 10.1155/2014/239708.

Rojas-Barrionuevo NA, Vernetta-Santana M, Alvariñas-Villaverde M, and López-Bedoya J. “Acute effect of acrobatic jumps on different elastic platforms in the muscle response evaluated through tensiomyography.” Journal of Human Sport and Exercise. 2017;12(3):728–741. 10.14198/jhse.2017.123.17.

Simunic B, Rozman S, and Pišot R. “Detecting the velocity of the muscle contraction.” Biology. 2007.

TMG™ Science for Body Evolution « Quantifying muscle function (tmg-bodyevolution.com)

Valle C. “Tensiomyography: An Update for Sport and Tactical Athletes.” SimpliFaster Blog.

Valle C. “TMG: A Secret Weapon in Sports Performance and Rehabilitation.” SimpliFaster Blog.

Wilson MT, Ryan AMF, Vallance SR, et al. “Tensiomyography Derived Parameters Reflect Skeletal Muscle Architectural Adaptations Following 6-Weeks of Lower Body Resistance Training.” Frontiers in Physiology. 2019;10:1493. Published 2019 Dec 10. doi:10.3389/fphys.2019.01493.