In the world of athletics, the amount of rest that is needed varies based on the sport. However, one undeniable truth at every level of sports is that rest is absolutely needed for each athlete and team to reach their potential. As fatigue sets in and legs get heavy, some coaches and programs have figured out that pushing further and harder is not the best option for optimal performance on game or meet day.

Running extra doesn’t make an athlete “tougher”—the old adage of dosing out punishments of up-downs, gassers, or some other tiresome discipline for not meeting goals, not listening to the coach, committing a penalty, or for simply losing is severely outdated. The idea of “the grind” has become the most overused term in sports. Winning games, races, meets, or matches becomes a lot harder when the athletes that need to go out and perform are tired due to archaic coaching that always preaches that they need to grind harder.

Winning games, races, meets, or matches becomes a lot harder when the athletes that need to go out and perform are tired, says @SFStormTrack. Share on XAnd I will be the first to raise my hand and admit I used to be that coach.

In the early 2010s, as a football, basketball, and track coach, if my players couldn’t get it done on game nights…well, we better run more the next practice because that will surely solve the problem. For the first 9 years of my track coaching career, volume was king: we needed to outwork everyone else and that’s how we were going to be good. At times, it seemed like it was working, but by the spring of 2018 I had started some self-reflection on what I was doing after learning about Tony Holler and Feed the Cats. My guys were successful, but what if I did less? Would they be more successful? Would they be ready for meets at a higher level? Were we going to take a step back?

There was only one way to find out. This article will look at data from the last four track seasons in Illinois as a way of defining how much volume—sprinters specifically—should be given throughout the course of a week or season, as well as looking at what rest looks like in our program.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9054]

BFC (Before Feed the Cats)

2017 was my ninth season as a track coach and second year as the head boys coach at Salt Fork HS, located in Catlin, IL (about 30 miles east of Champaign). We had just had one of the most successful seasons in program history, with almost the whole team due to come back in 2018. We qualified for State in the shot put, discus, long jump, triple jump, 4×800, 110H, 100, 300H, and narrowly missed the 4×1, finishing 3rd.

After the highs of being sectional runner-up and getting that many athletes to State, the following Thursday at prelims could not have been any more disappointing. We qualified in a total of one event (discus) for finals and came back with no medals. Coming off the successes of 2017, and everyone aging up a year, we were clearly going to be better—so as a coach, I just needed to keep the status quo.

When 2018 rolled around, we were highly anticipating success and were ready to go. Week one of our season began on February 26th, with our first meet not coming until after our third week of practice. At the time, we did not run much of an indoor season, so we had to get in lots of volume to make up for that. During our first three weeks of the season—15 practices, no days off during the week—the sprint crew averaged a whopping 4,583m/week. Week 2 was the heaviest volume week of the year, topping out at 5,750m.

Those first few weeks consisted of lots of timed runs in the gym of anywhere from 10 seconds to 60 seconds, repeat 200s all the way up to 600s, and tempo runs with lots of jogging, workouts that got us to a solid place in 2017. Rest days or easy days consisted of fartlek runs, circuit days (which may be considered X factor workouts, but with about 500% more volume), and sometimes just more sprinting. We also started every day with a 400 warm-up jog and a 400 cool-down jog, as if we didn’t already do enough running. Pre-meets and days after meets, regardless of meet volume, consisted of more sprinting (or what I perceived at the time as sprinting). Anywhere from 900-1200 meters of volume the day before or after meets was not uncommon, but again, we were good. It must be the workouts that were getting us ready to go.

Pre-meets and days after meets, regardless of meet volume, consisted of more sprinting, says @SFStormTrack. Share on XTo avoid being redundant and going through each week and each workout, I will fast forward to the end of the season. The team won our county and conference meets as well as the first ever Sectional Title for the program in school history. We broke five school records during the season and competed in 13 events at the sectional meet, qualifying for State in 11 of those 13 events. We had a top ten finish—maybe even a trophy—on our minds as we traveled to Charleston, IL, the following week for our State meet. Much like the previous year, we faltered when it mattered most. We went to the finals in the 4×800, 800m, and 300m hurdles. We ended up missing a medal in the 4×800 and finished 22nd as a team at the meet with a total of 12 points. Out of ten total competitions between prelims and finals in the sprints and jumps, we saw only two personal records (PRs).

As I began my reflection on the season, it was clear that we needed a change and it needed to start with me. Our total volume in meters per week, including practice and meets, was 3,896 for sprinters. We were still averaging around 2,100 meters of volume/week in May, including meets and practices for our sprinters. That did not even include warm-ups or cool-downs. As I looked back over the last month of our season, we were slowing down as the season went on. The number of PRs we were having went down dramatically over the season:

- County Meet on May 4th—10 PRs in sprints and jumps

- Conference Meet on May 7th—7 PRs in sprints and jumps

- Sectional Meet on May 18th—4 PRs in sprints and jumps

- State Prelims and Finals on May 24th and 26th—2 PRs in sprints and jumps

As great as the season was, I looked in the mirror and realized that something had to change if we were going to break through from being good to being great. During May of 2018, I had started reading this breakthrough philosophy on sprinting called Feed the Cats. While too late to really fully implement it during the 2018 season, I began to use some of the lactic workouts in spots. Just not the right spots—adding to an already high-volume load, I decided to throw in some lactic workouts during our championship season. However, as I read more and more into these new ideas—at least new to me anyway—I began to buy in (with some hesitancy at first). This led to the great transformation in 2019.

As I read more and more into these new ideas in Feed the Cats—at least new to me anyway—I began to buy in (with some hesitancy at first), says @SFStormTrack. Share on XAFC (After Feed the Cats)

I spent the fall of 2018 reading as much as I could on low dosage, low volume sprinting. I created potential practice plans, adding in rest days. Actual rest days. Admittedly, it was hard for me to give days off and think it was going to be meaningful or helpful, so most of our rest days were still spent together rolling out or working on mobility.

The team had many of our top guys back again for one more year, and I had one goal that I wanted to instill in the team from day one. I started recruiting the hall heavily that year looking for guys that would fit the mold of what we wanted to accomplish. When we had our first team meeting in January, we had 18 guys who bought in with the idea that this season was going to be a State Championship season and we were going to go outside the box to accomplish that. I thought I was hesitant in changing, but they were even more hesitant to these new ideas.

We revamped our indoor schedule to include four meets before the Top Times Meet (unofficial Indoor State in Illinois) instead of the usual one. With a meet on Saturday of that first week, sprinters put in a total of 690m at practice that week, compared to 4,300m the year before. After four weeks of indoor season, the sprinters averaged 1,056m/week of volume, which included meets and practices. In 2018, we averaged 4,712m/week of volume during indoor. In 2018, we used arguably three of our four fastest sprinters in the 4×200, and while only running it once, we only managed to run a 1:41.65. In 2019, with two carryovers from 2018, a mid-distance runner, and a sophomore who had never ran track before, we managed to run a 1:35.38, which was the fastest 1A time in the state when it was run in the middle of March.

Our top runner, Caine Wilson, couldn’t run under 9 seconds in the 60H or under 54 in the 400 in 2018. In 2019, with increased rest and decreased volume, he finished 2nd in the state at Top Times in the 60H, running an 8.47 as his best time; in the 400, 51.70 and again 2nd at Top Times with a volume that decreased by 78% from the year before over the first four weeks. These are just two examples—the same thing happened with our top sprinter in the 60, our top mid-distance runner (who was trained more towards sprinting than distance), as well as our 4×400 team in indoor. Volume went down and meet times went down as well.

As we moved outside and our meet schedule got heavier—typically 2 meets a week on Tuesdays and Fridays—I wasn’t sure how we would adjust to this new method of training. With our meets where they were during the week, it left no time for training. It allotted us two pre-meet days and a rehab day. Throughout the outdoor season, we averaged 395m/week of volume at practice, with 6 out of 9 weeks having less than 200m of volume. In 2018, sprinters averaged 2,455m/week of volume at practice with virtually the same outdoor schedule. This was a decrease of 84%.

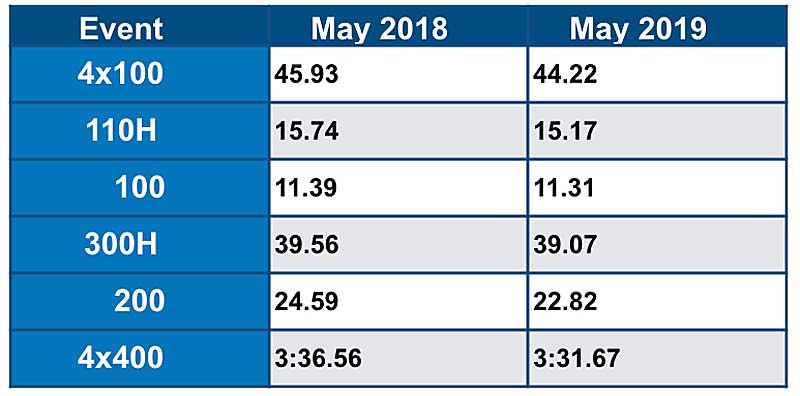

The end of the season resulted in a much better finish then the previous season. We won our county, conference, and Sectional meets again. We advanced to the State meet in 11 events, the same number as the year before. The difference this time is that we advanced to the finals in seven events, finished with 40 points, and brought a State title home to Catlin. While our number of PRs went down over the last few weeks of the 2018 season, the opposite occurred in 2019: we were peaking and fastest when it mattered the most. We had 13 PRs between the Sectional and State meets in 2019, compared to 6 the year before. Athletes ran their fastest 110H, 300H, 100, 200, and two fastest 4×100 times at State. In our top sprint events, with many of the same personnel, we dropped our averages from the year before.

Post 2019

After the 2019 State Championship, there was no turning back in my pursuit of removing as much volume as I possibly could while still focusing on speed. We started a speed training program over the winter that attracted athletes from various sports in the school and we were primed for another great season in 2020. However…we all know how that year ended.

There was no turning back in my pursuit of removing as much volume as I possibly could while still focusing on speed, says @SFStormTrack. Share on XSo, the 2021 season came with a completely new set of challenges. I had essentially a brand new team, with only one holdover from 2019 (a sophomore member of the all State 4×100 team). The vast majority of the rest of the team were sophomores or freshmen. Only 2 of the 15 team members were non-football players. Usually that is a good thing; however, in Illinois that spring, football was played until the end of April, so I didn’t get 90% of the track team until April 26th—which was exactly 53 days until the State track meet.

Sprinters who were on the football team ran two lactic workouts that year and averaged 367m/week at practice with only two weeks over 600m. We used meets as practices and continued to keep our volume low, especially with athletes new to the fold. We decreased our total weekly volume 12% from our 2019 total to keep everyone as fresh as possible. I finally started taking practices off altogether after meets; sometimes we would still come in, but many days after meets, sprinters were off and went home. To me, rest was even more important in 2021 due to most athletes coming straight off of basketball and football with no breaks, and two key relay members also on the wrestling team at the same time as track season (2021 was weird for high school sports).

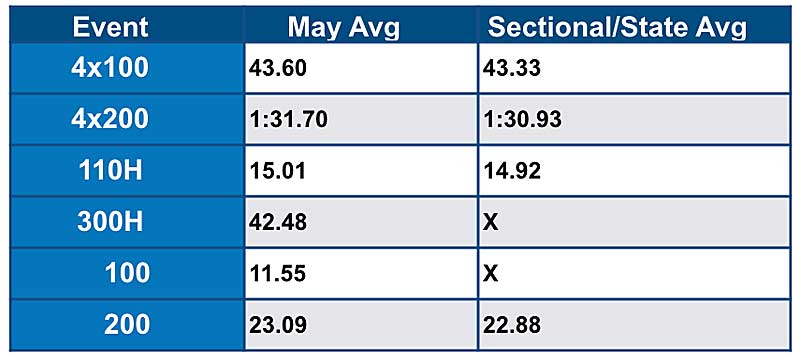

I knew I had a talented group, but still anticipated a drop off with how young they were. However, the data showed that lack of volume during the season was a heavy contributing factor to the success at the end of the season. We had another 11 PRs between Sectionals and the one-day State meet (instead of the usual two-day meet.) We qualified in seven events, finishing in the top four in three of the four sprint events we qualified in. We ran our two fastest times of the season at Sectionals and State in the 4×100 (44.03 avg), 4×200 (1:31.94 avg), 110H (15.09 avg), and 300H (42.58 avg). We set school records in the 4×100 and 4×200, and scored 38 points to finish as the State runner-up for 1A in 2021.

2022 had the makings of another great season for our team, so I wanted to get a jump start on the season. Typically, we would start the season the last week of February; in 2021, we started 3 weeks earlier in order to practice for a few weeks and not have to worry about meets. I also felt that we needed more time to work on our pure speed.

After tracking our athletes over the previous few years, it was apparent that our athletes were getting slower post-track season until the next season started due to increased volume in other sports. Tracking 40 times throughout the year, our sprinters were on average losing 3-5% of speed in the track offseason. Keeping volume low and increasing pure speed became the first priority. We still kept our overall volume relatively low, but increased from the previous year, which would be a necessity based on how short the previous year was.

It was apparent that our athletes were getting slower post-track season until the next season started due to increased volume in other sports, says @SFStormTrack. Share on XOur practice volume was 472m/week for the season, higher than 2021, while our total volume/week including meets was 1047m, which was virtually the same as the year before. Once we got outdoors, six out of nine weeks had less than 150m of volume total at practice. Pre-meet days were reduced to 45 minutes or less. Post-meet days typically became complete off days for sprinters. We never came in on the weekends and took off 15 weekdays during the season, more than double the most I have ever given off in a season.

Once again, however, I felt that we were fresher than most teams when we got to the end of the season. We had 16 PRs between Sectionals and State, setting new school records in the 110H, 4×100, and 4×200. Our May averages continued to drop:

We also had our first All-State jumper in school history. In the triple jump, he had five of his six best career jumps at the State meet, going over 42 feet five times and 43 feet one time. It was not a coincidence; his volume was down to almost nothing over the last few weeks of the season, so his legs were fresh in a very taxing event.

The same can be said for our incredibly successful throws unit. Volume had been king with lots of success, but over the last two seasons, as we got deeper into May, we dropped the number of throws in a given week. It has yielded four all State performances, including two discus State championships at the 1A level. Not only did our times/jumps continue to improve when it mattered the most, but we brought home our third consecutive State trophy and our second State Championship in three seasons.

Volume Decrease/Rest Increase

While the data on volume has been apparent throughout the article, I would like to take some time to discuss what rest actually looks like in our program. Many times, rest is just taking the day off and going home. However, when we are at practice and rest is going to be utilized, we incorporate several measures that we believe have shown increased performance when we need it.

We try to work on hip and ankle mobility at least twice a week throughout the season. We spend time using foam rollers and massage guns before and after practice to work on leg muscles and back muscles. We encourage athletes to make time to go to the chiropractor. Last season, we bought four pairs of Air Relax boots that athletes would use the day after meets when they felt fatigued, or sometimes even at meets.

We try to work on hip and ankle mobility at least twice a week throughout the season, says @SFStormTrack. Share on XWhile decreasing volume was the most important and most significant factor to change, we also needed to look at how we could spend our time at practice to be most beneficial. Not only did we increase our restorative measures, but we also increased our time that we spent teaching technique and focusing on little details in form, block starts, and handoffs. These are low-volume and low-energy activities that have a high impact on our performances.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9192]

Conclusion

Many coaches are slow to change. I was guilty of being one of those coaches. However, there comes a point to look at quantifiable data and say, “the proof is in the pudding.” If your team is faltering when it matters the most—if your football team or basketball team or track team is great to start the season but fatigue sets in halfway through and the season becomes a lost cause—it may be time for some reflection on the atmosphere of training you are creating to set your athletes up for success.

Do I anticipate bringing home a State trophy every single year until I hang up my stopwatch? No. However, I plan on continuing to set my athletes up for success by minimizing how much activity they perform, increasing rehabilitative measures and rest, and continuing to educate myself on best practices. The measures that have been implemented in the Salt Fork Track and Field program are continually being evaluated and adapted but have caused a massive increase in the success of all our athletes and our team as a whole.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF