[mashshare]

Introduction

“In order to become a wrestler one should have the strength of a weight- lifter, the agility of an acrobat, the endurance of a runner and the tactical mind of a chess master.” — Alexandre Medved

Wrestling is a dynamic, high-intensity combative sport that requires complex skills and tactical excellence for success (Zi-Hong et al., 2013). To be successful on the world stage, wrestlers need very high levels of physical fitness. Wrestling demands all qualities of fitness: Maximal strength, aerobic endurance, anaerobic power and anaerobic capacity. To be effective, wrestling techniques must also be executed with high velocity (Zi- Hong, 2013). Enhancing the functional ability of each of these physiological qualities is the primary aim of the Wrestling S&C Coach.

Athletes who wrestle at an elite level (international caliber) are often required to perform strength, power, and endurance training concurrently with aims to achieve improvements in all performance measures. Concurrent training is defined in the literature as strength and endurance training in either immediate succession or with up to 24 hours of recovery separating the 2 exercise modalities (Reed at al, 2013). Much of the research indicates a possible attenuation of strength and power as a result of concurrent training while aerobic capacity and endurance performance appear to be minimally affected (O’Sullivan, 2013). Concurrent training also applies in the technical and tactical development of the wrestler. Often the rigorous demands of practice can create a high level of fatigue, which must be considered when we advise a training program.

Although concurrent training does allow for the training of multiple physical qualities, it does place great adaptive demands on the athlete. The acute responses and long-term adaptations of the Neuromuscular and Neuroendocrine systems seem to be the most relevant areas to investigate with this population. Many factors appear to determine the adaptive ability of elite wrestlers to concurrent training, including the athlete’s level of physical conditioning, overall life stressors, nutrition1, overall training volume, and the training program design.

1Psychological and nutritional aspects are beyond the scope of this article.

Gaining insight into the most optimal ways to minimize interference by understanding models of fatigue are the cornerstones of this article. Also, understanding and analyzing elite level wrestlers’ physiological data gives practitioners insight into the benchmarks their athletes must reach to perform at the highest level.

The objectives of this article are as follows:

- To highlight the physiological profile of elite, word-class male and female wrestlers.

- To review concurrent training literature and observe the adaptations that result from different methodology.

- To offer some programming strategies to minimize the interference effect and optimize the adaptation process.

- To provide some future study design directions for researchers in this area so that the training programs being evaluated are an accurate representation of elite freestyle wrestling performance.

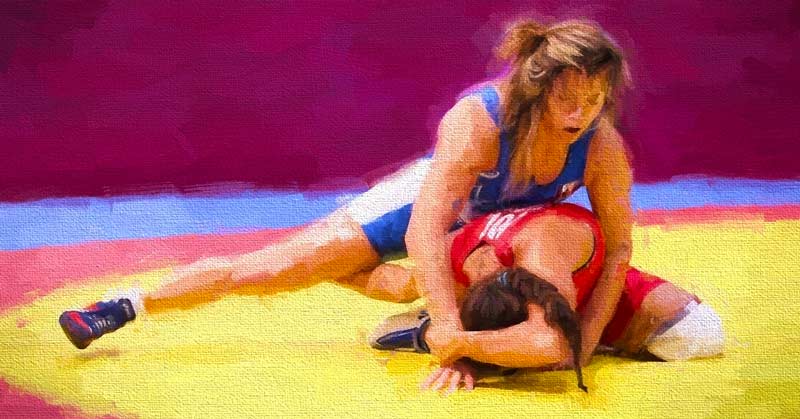

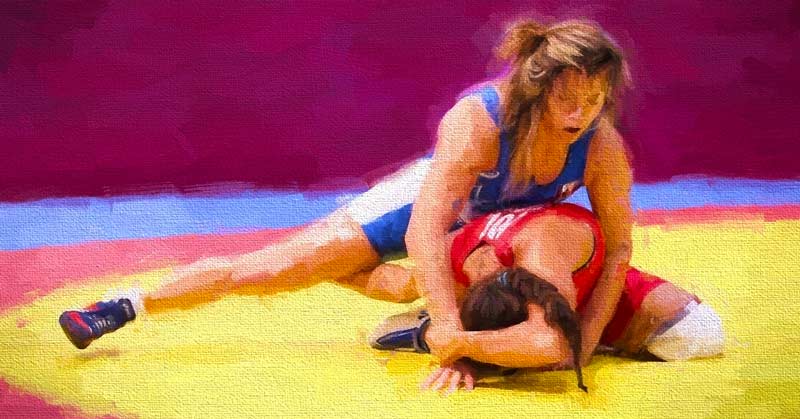

The Sport of Wrestling

Wrestling can be traced back to ancient times. “During the Ancient Olympic Games, from 708 B.C., wrestling was the decisive discipline of the Pentathlon. In fact, it was the last discipline to be held – after the discus, the javelin, the long jump and the foot race – and it designated the winner of the Pentathlon, the only crowned athlete of the Games” (United World of Wrestling Website).

Freestyle wrestling first made its appearance in 1904. In Greco-Roman wrestling only upper body moves are allowed, whereas freestyle includes upper body and leg wrestling. Both styles are currently offered in the Olympic Games and other international competition (Horswill, 1992). In September 2001, the International Olympic Committee announced the inclusion of Women’s Freestyle wrestling at the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens (Wrestling Canada website: Spectator Resources, 2016).

Wrestling can be categorized as an intermittent, combative sport that requires maximal strength and power demands of the entire body, with a high anaerobic energy metabolic demand (Passelerague & Lac, 2012). It is also a weight class sport. Competitors are matched against others of their own size. This reduces the exclusion of smaller athletes in sports where physical size gives a significant advantage.

Wrestling activity is extremely chaotic in nature, encompassing repeated explosive movements at a high intensity that alternates with submaximal work. Thus, the primary energy systems utilized are the anaerobic adenosine triphosphate-creatine phosphate (ATP-CP) and lactic acid systems, within the scope of the aerobic system. It has been demonstrated that there are no major physiological differences between wrestlers of both freestyle and Greco-Roman styles (Mirzaei, 2009).

In 1904, freestyle wrestling was first introduced during the St. Louis Games. At the Stockholm Olympic Games in 1912, freestyle wrestling was absent from the program, and ‘Icelandic wrestling’ was instead organized. Wrestling matches took place on three mats in the open air. They lasted one hour, but finalists wrestled without a time limit (United World Wrestling Website). Over the past century, the match structure of international Freestyle wrestling has taken on several forms evolving past a continuous 5-minute period in the late 1990’s to the current: Two, 3-minute periods with a 30-second rest between periods. A match may be won by “fall”, by technical superiority or by points (Wrestling Canada website: Spectator Resources, 2016). During tournaments, multiple matches per day may occur over the course of a few days. There are no rule differences for female competitors. There is no overtime period; a tie is broken by point classification in the second round.

The Physiology of a Match

National, international and Olympic wrestling events are formatted in such a way that athletes are required to compete in multiple matches over the course of hours or for a few consecutive days (Barbas et al., 2011). This scenario, coupled with a significant weight loss (>6% of total mass) may have implications for performance.

Barbas et al. examined the physiological responses of 12 elite male Greco-roman wrestlers during a one-day wrestling tournament (2011). In 2011, the rules were slightly different than they are now. There were 3 rounds, each 2 minutes in duration separated by 30 seconds rest, totaling a maximum of 6 minutes of work. Knowing this, the acute physiological responses may not be valid in today’s rule system. In Barbas’ study, they observed a mean heart rate response of 85% of maximum and a peak HR of 96-98% of maximum during a match. Blood lactate concentrations exceeded 17 mM, which was consistent with other research findings. According to Kraemer et al., lactate levels may be related to glycogen depletion due to athletes’ restricted food intake and insulin’s maintenance during a wrestling tournament (2001). Elite wrestlers typically compete in a chronically dehydrated state. Thus, it has been hypothesized their fluid regulatory systems have been reset to a new “normal” indicating a compensatory response (Kraemer et al. 2001). Kraemer et al. (2001) also reported that elite wrestlers, in this typical hyperosmotic state, are still capable of competing at an elite level demonstrating a significant resiliency suggesting an adaptation of the hypothalamic control of osmolality regulation.

In Barbas’ study, each simulated match went the full 6 minutes. The athletes completed a total of 5 matches separated by varying timelines. Blood work showed an increase in muscle damage markers during the course of the day/tournament, with the upper limbs being more affected (2011). The hormones cortisol, norepinephrine and epinephrine also increased after each match and testosterone levels declined, creating a pro-inflammatory environment (2011). Other findings included that most performance markers (VJ, HB, Bear Hug, HG) deteriorated (»13–16%) after the third match as compared with baseline. Vertical Jump performance was the only metric to restore back to baseline for the final match (*after 5 hours of rest) (Barbas, 2011).

The authors noted that a one-day wrestling tournament might decrease performance match after match (2011). Upper body strength and performance appeared more susceptible to decline during the course of a 1-day wrestling tournament than those of the lower-body musculature as previously shown by Kraemer et al. (2001). Interestingly, 5–6 h of recovery between matches 4 and 5 was inadequate to induce a perceptual recovery. Similar findings have also been reported during a two-day wrestling tournament (Kraemer et al. 2001).

The ability of wrestlers to fully recover before their next match during a tournament is vital for performance and beyond the scope of this article. However, it is important to understand the physiological responses of well-trained wrestlers when competing multiple times per day. It is also important to note that the practice of weight cutting within reason (5-6% total mass) does not appear to interfere with performance determinants as shown by Barbas’ works and Kraemer’s study on elite freestyle wrestlers (2001).

The Physiological Characteristics of Elite Senior Male and Female Freestyle Wrestlers

One of the challenges confronting coaches and sport scientists is to “understand the physical and physiological factors contributing to successful wrestling” (Mirzaei et al., 2009). The use of lab and field tests for the measurement of the current status of the wrestler can provide the sport scientist with valuable information relative to the wrestler’s current physiologic capability and can allow them to compare the athlete with reference values from comparable peer groups.

When reviewing the literature on physiological profiles one must consider the year(s) of publication. Since there have been numerous rule and thus ‘style’ changes over the past 40 years, some of the earlier data may not be as relevant in today’s version of freestyle wrestling. For example in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s Freestyle match duration changed from 9 minutes to 6 minutes. After 1988, Freestyle wrestling changed from 2, 3-minute periods with one minute rest to a continuous 5-minute period (Callan et al., 2000). Currently, the athletes compete for two, three-minute periods separated by 30 seconds rest. The knowledge acquired regarding the changes in match design is helpful in the bigger picture.

Understanding and capturing the evolution of physiological profiles of elite freestyle wrestlers is fundamental, providing normative data for strength and conditioning coaches and providing benchmarks for young, aspiring competitors. It has been demonstrated that physiological variables alone can account for “approximately 45% of the variance seen between successful and less successful Freestyle wrestling Olympic contenders” (Callan et al., 2000).

Body Composition

Wrestlers are characterized by specific morphological characteristics: “accentuated width and girth of the body, proportionally long arms and short legs, a large percentage of active muscular body weight” (Mirzaei et al, 2010). Data collected on average body fat values for Canadian elite male freestyle wrestlers in 1984 were 8.2% for all weight classes excluding the superheavyweights (Sharratt, 1984). Horswill (1988) reported average values of 7.2% bodyfat. Callan et al. (2000) collected data on elite male American wrestlers, excluding open class heavyweights, and found them to lie between 5 and 10 percent bodyfat. Mirzaei et al (2009) studied Iranian Junior freestyle wrestlers and noted an average bodyfat percentage of 10.6%. No published data can be found on the body composition of elite female wrestlers.

Although anthropometry and body composition are important areas to study when profiling athletes, it is not the focus of this article as its relationship to elite freestyle wrestling performance is not clear. Also, the effects of weight loss on performance will not be covered in any depth in this article. It appears that purposeful weight loss and its effects on performance outcomes and physiological function are highly individual and dependent on the magnitude of the weight loss. The major limitation of all previous studies on weight loss and physical performance in wrestlers is that inferences cannot be made to actual wrestling performance (Horswill, 1992).

Pulmonary and Cardiac Function

Very few studies examined pulmonary function amongst this population. Sharratt et al. (1984) found the pulmonary function, resting blood pressure and hematology measurements to “be typical of healthy adult males” and there were no sport-specific differences on these parameters. Sharatt et al. (1984) also reported in elite senior level wrestlers, maximum minute ventilation was low relative to the peak oxygen uptake values and high levels of blood lactate. He hypothesized that elite wrestlers may “hypoventilate during maximum exercise as a result of becoming conditioned to years of restricted breathing” (Sharratt et al., 1984). No data was found on elite females. There is, perhaps, a need for more research in this area.

Data collected on collegiate wrestlers have cardiac stroke volumes and left ventricular volumes similar to non-athletes but smaller than those of endurance-trained athletes. The wall and septum of the left ventricle were greater in the wrestler than in the non-athlete and endurance athlete. Because wrestling does not demand the high cardiac output or stroke volume of endurance sports, an expansion of the left ventricle chamber with training does not occur. In general, there is limited data on Pulmonary and Cardiac function on this population.

Muscle Morphology

Houston et al. (1981) identified the vastus lateralis muscle group as being a representative muscle for the study of wrestling performance. They found significant glycogen depletion in this muscle combined with an elevated blood lactate concentration following maximal effort wrestling. Scientists also biopsied the muscle group; the samples were 52% fast twitch, implying an average aerobic capacity at the cellular level (Sharratt et al., 1984). Sharratt et al. (1984) also measured the succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) activity in the vastus lateralis of senior wrestlers as an indicator or aerobic potential. They reported an activity level indicative of endurance adaptations but not to an exceptional level. Gollnick’s (1982) work indicated that although wrestlers have higher SDH levels than deconditioned males, the levels do not reflect the higher VO2 values the wrestlers possess. The published data in this area was collected on male athletes of varying levels in the mid-1980’s. This is a possible area of future investigation with both elite male and elite female wrestlers.

Strength

Strength is defined as the ability to exert force under finite conditions, independent of time and space. Strength is very much related to both velocity and biomechanics, so interpreting results of strength data when one cannot observe and monitor technique is limiting. In the wrestling literature, strength is often measured by a percentage of 1RM on a multi-joint/primary lift, by hand grip dynamometry and often expressed relative to the mass of the athlete (relative strength).

Rules changes in the 1970’s changed the tactics of the sport of Freestyle wrestling placing importance on an aggressive style of wrestling versus holding or ‘stalling.’ As a result, improving the dynamic strength of wrestlers, in all muscle actions (concentric, isometric and eccentric) became a training focus. Horswill’s review in 1992 compared successful male elite2 wrestlers to less successful wrestlers and found that greater strength to be an advantage. However, although his work is very comprehensive, Horswill did not use typical primary exercises for strength assessment. Thus, his data is not particularly useful for the strength and conditioning coach. Yoon (2002) also noted in his works that successful male wrestlers showed higher dynamic and isokinetic strength than unsuccessful wrestlers.

2Elite = International level competitor

A unique approach in how to address strength needs for this population was seen in East Germany. They tested for maximal strength through a 1-repetition max; speed strength by timing the lifting of a weight (75% of your weight class weight) for 8 reps; and tested strength endurance with maximum reps at the weight class standard. They also had performance standards for each weight class (2010 Annual Review of Wrestling Research).

Dr. Boris Podlivaev also shared an updated version of his performance standards at the FILA Scientific Congress held at the Moscow World Championships.

A brief synopsis is included in the chart below, based on weight class. A more comprehensive list with wrestling-specific tests can be found in the literature (Podlivaev, 2010). No information was found on the protocols for these tests or why partial scores were given. The numbers for bench press and cleans appear to be very low as compared to the East Germans standards.

| TESTS | 55-60 kg | 66-84 kg | 96-120 kg |

| 30 m sprint (s) | 4.53 | 4.59 | 4.63 |

| 60 m sprint (s) | 7.9 | 7.79 | 7.8 |

| 100 m sprint (s) | 12.98 | 12.87 | 13.27 |

| Pull-ups (n) | 34.4 | 32.4 | 22.6 |

| Push-ups (n) | 70 | 68.1 | 57.6 |

| Cleans (kg) | 74 | 82 | 113.5 |

| Bench Press (kg) | 83 | 92.50 | 125.5 |

| Hanging Leg Raises (n) | 18.2 | 15.3 | 14.4 |

| 800 meter sprint (min) | 2.47 | 2.51 | 3.20 |

| 8 km Cross (min) | 28.34 | 29.18 | 36.31 |

Mizraei’s case study on a World Champion Greco-Roman male wrestler (2010) collected pull-up data of 50 repetitions, (versus the National Iranian norm of 37 reps). This is considerably higher than the Russian data, but ‘how’ the tests were conducted (strict reps versus momentum) was not observed, so the data is difficult to compare.

The research on elite females by Zi-Hong et al. (2013) used several isokinetic tests at two different velocities as well as 5 isotonic exercises for evaluation. These included: Deep squats, Prone rowing, Olympic style deadlifts and Power cleans from the floor and a unique lift called the hold and squat to measure strength in elite female wrestlers. These lifts were chosen because they are part of the Chinese female wrestlers training program. Four weight categories were tested (48kg, 55kg, 63kg, and 72kg). Average values for each lift, across four weight categories, are as follows:

| Wt. Category | Deadlift | Deep Squat | Prone Rowing | Power Clean | Hold & Squat |

| 48 kg | 109 kg | 90 kg | 64 kg | 74 kg | 104 kg |

| 55 kg | 126 kg | 100 kg | 74 kg | 75 kg | 104 kg |

| 63 kg | 123 kg | 99 kg | 76 kg | 77 kg | 110 kg |

| 72 kg | 150 kg | 106 kg | 78 kg | 82 kg | 125 kg |

To summarize Zi-Hong’s research, it was found that an Olympic or World Championship medalist generally demonstrated the highest 1RM value for any weight category. Other research also indicated that more experienced and successful wrestlers, as defined by the number of international tournaments, were also stronger (Zi-Hong, 2013).

It is important to mention very few papers used what would be typical strength and power exercises prescribed by a strength and conditioning coach to train and measure strength. It would be ideal to see 1RM strength data on the top male and female Freestyle wrestlers using: Deep squats, bench press, prone rowing and cleans as exercises.

Anaerobic Power

Power is defined as the product of force (in Newtons) and velocity (in meters per second). The ability to produce a high power output is important for wrestlers. Power in wrestling is associated with quick, explosive movements that lead to control of the opponent (Horswill, 1992). Average power or mean power is often equated with anaerobic capacity. It has been reported that anaerobic power and anaerobic capacity may help to differentiate between successful and less successful male and female wrestlers.

A freestyle wrestlers’ anaerobic performances are much more similar to power athletes (sprinters, throwers, weightlifters for example) than endurance athletes. On the basis of equivalent bodyweights (W/kg), male distance runners and ultra marathoners have leg power values of 8.9 and 9.3 W/kg. In contrast, male powerlifters had values of 9.5 W/kg, male college wrestlers 9.4 W/kg, and male gymnasts 9.1 W/kg (Horswill, 1992).

Similarly, the anaerobic power of the upper and lower body of male wrestlers is much greater than the corresponding values in nonathletic men of similar age (Horswill, 1992). The published values on most wrestlers at any level exceed the sixty-fifth percentile of lower body anaerobic capacity and anaerobic power of nonathletic adult males (Horswill, 1992). At the time Horswill published his review, there was very little data comparing elite and non-elite wrestlers using the Wingate test.

Lower body anaerobic power has been evaluated using a vertical jump test with counter-movement. The 1997 United States male freestyle wrestling world team averaged 60 cm (Utter et al., 2002). Unpublished data from the US Olympic Committee (Callan et al., 2000) showed Greco-Roman male wrestlers to have average counter-movement vertical jumps of 62 cm. Russian data by Podlivaev had average scores ranging from 56.70 cm to 66.10 cm. Protocols for the Russian data were not given, and elite female scores on vertical jump were not found.

Upper body anaerobic capacity is frequently evaluated with arm cranking on bicycle ergometers. Performance of the upper limb muscles reflects the potential of muscles to derive ATP via fast glycolysis.

Horswill et al. (1992) had 12 well-trained male collegiate wrestlers perform a multi-stage upper body Wingate test, with 6.5 g per kg of body weight (8 x 15 seconds with a 30 second rest between stages, over 6 minutes). A power production curve over the 8 sprints is graphed. They found sprint power ranged from 3.7 to 4.6 W/kg/bw. This testing has not been reproduced elsewhere and was not conducted on elite level male or female wrestlers, so it is difficult to interpret. Callan (2000) reproduced a similar test with 5, 30-second efforts designed to simulate a 5 minute match. The data collected on his study may not be valid with the rules in place today, as the match periods are shorter. Upper body Wingate normative data seems exclusive to these precise studies.

Female wrestlers in the Zi Hong study (2013) performed a standard wingate test, using a higher relative load of .08 x body mass and demonstrated maximal peak power values between 7.04 W/kg and 9.12 W/kg. It is important to mention, for the purpose of comparison, most normative data using the 30 second Wingate (lower body) for elite female athletes is based on .075 x body mass. It must be noted male athletes generally have 10% and 17% higher peak and mean power than women when expressed relative to kg lean body mass (LBM).

Blood lactate readings have been evaluated post-match as well as after Wingate tests and other tests of maximal effort in several studies. Average post-match values (5 min) for elite males on the Turkish National Greco-Roman team in 2006 was 12.3 mmol/L. In Zi-Hong’s works post-Wingate blood lactate values reached an average peak of 11.69 mmol/L (2013). What might be more interesting and relevant is Dr. Ramazan Savranbasi’s work where the Lactate recovery co-efficient is calculated following a match or a standardized exercise bout (2010 Wrestling Research Annual Review).

In Zi-Hong’s work with elite females, mean peak power, relative to body mass (in Watts per kilogram), fatigue index (%) and 400-meter time demonstrated no significant difference between weight categories (2013). The 400-meter time was, however, significantly correlated with maximal peak power.

Callan et al. (2000) investigated a rope climb as a means to evaluate upper-body muscular anaerobic power and endurance. The athlete was instructed to climb a 5.6-meter rope hand over hand arms only. The total time was recorded to cover this distance. Although this is a highly task-specific test, it is a useful field test. Average times were 9.3 seconds for the 1997 World (male) U.S.A. Freestyle team. No other studies have replicated this test making it difficult to create an optimal standard or correlated a result with wrestling performance. The Russians have used a 4-meter hand only climb, but only test results were given (time) versus exact protocols.

Anaerobic capacity was measured in elite Canadian freestyle male wrestlers using the Anaerobic Speed Test (Sharatt, 1984) The athletes performed two maximal efforts, separated by a 4-minute rest. Blood lactate values were taken 5 minutes into recovery. Athletes ran the first repetition in an average of 55.6 seconds for all weight classes (individual weight classes were not indicated) and for the second interval, an average of 45.3 seconds. No normative data for elite wrestlers using this test is available. Blood lactate levels read an average of 14 mmol/L, similar to values for other athletes in sports with a major anaerobic contribution (Sharatt, 1984). At that time, the best Russian wrestler generated over 20 mmol/L (Sharratt, 1984).

Anaerobic power and capacity may be the points of difference between successful and less successful wrestlers. The anaerobic power and capacities of elite junior (18-20 years old) wrestlers are greater by as much as 13% than those of non-elite wrestlers of similar weight, age and wrestling experience (Horswill, 1992). The Olympic and World Champion female test results on both the Wingate and 400-meter run are at the upper end or the best value (Zi Hong et al., 2013).

With respect to anaerobic testing, it appears there are no universal tests for wrestlers and that perhaps a battery of tests might serve to highlight power objectives as well as limiters in performance.

Speed of Movement

The speed at which an athlete move his body in response to a stimulus is an important quality in wrestling. Much of the research on wrestlers on this quality dates back to 1958, where they determined reaction time to be non-critical (Horswill, 1992). Taylor (1979) was the first to establish a wrestling specific test of reaction time, but the subject pool was too small (Horswill, 1992). More recently, Mirzaei et al. (2010) collected data using an instrumental jumping pad in front of a reaction time apparatus. The athletes were instructed to react to a visual stimuli by moving his foot from the pad. The best of 3 trials was collected for each subject. The National norm in Iran was 391 ms (Mirzaei, 2010). No other published data from other countries is available. And no published data on control subjects were available.

Very few researchers have investigated and published linear speed or agility data on wrestlers. Mirzaei et al. (2009), tested speed with a 40-yard sprint, like the NFL combine. Elite, junior wrestlers performed the sprint in an average of 5.14 seconds. The agility test was a 4 x 9-meter shuttle (Mirzaei, 2009). Average times were 7.6 seconds touching a sensor. No information was captured on the logistics of testing and whether or not the 40-yard times were electronic. There is great likelihood that these tests are conducted routinely with elite male Iranian wrestlers, but the data was not accessible via conventional routes.

Flexibility

During wrestling, the limbs are forced through extreme ranges of motion. When flexibility is limited there may be performance impairments. However, there is no conclusive evidence that flexibility training directly improves wrestling performance.

In Horswill’s research findings, wrestlers had a greater rotation and abduction and adduction of the shoulders than nonathletic controls (1992). While neck flexibility was also high in the wrestlers, wrist flexibility was lower than the non-athletes (Horswill, 1992). Comparing the successful wrestler with the less successful wrestler, it was shown that flexibility might be a discriminating variable (Horswill, 1992). Yoon (2002) reported the flexibility of elite wrestlers is higher than lower level wrestlers.

In Mizraei’s works, he evaluated flexibility on a senior world champion Greco-Roman wrestler (2010). The tests included were: The sit and reach, the shoulder-wrist elevation test and the trunk and neck-elevation test. The latter two tests are essentially tests of extension. Scores were listed on a table with no units of measure leaving them difficult to interpret. Other normative data for elite wrestlers using these tests were not found.

Generally speaking, flexibility of elite male and female wrestlers must be investigated in a comprehensive manner to establish normative values.

Aerobic Power & Capacity

When wrestling matches were 9 minutes long (1976), a much higher emphasis was placed on aerobic power. Coaches were recruiting athletes with VO2 max’s 60-70+ ml/kg/min (Sharratt, 1984). Today, matches are shorter (2 rounds of 3 minutes each, with a 30-second break). Therefore, it is possible that aerobic power is not as critical for match success as previously suggested. According to Zi-Hong’s work, maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max) does not appear to differentiate between elite female wrestlers at different levels of competition (2013). The capacity to provide energy by means of anaerobic pathways is now considered more critical to performance.

In general, elite male wrestlers have peak V02 values of between 50.4 and 62.4 ml/kg/min (Horswill, 1992). Yoon (2002) reported that the maximal oxygen uptake of national and international male wrestlers taking part in international competition has been shown to be 53 to 56 (ml·kg-1 min-1). An article published by Huber-Wozniak (2009) found an average Vo2 in male elite wrestlers was 59.8 ml/kg/min, and females were 49.7 ml/kg/min. Total oxygen uptake at the anaerobic threshold, expressed as a percentage of VO2 max, was higher in the female wrestlers (Huber-Wozniak, 2009). Higher oxygen utilization at anaerobic threshold might provide useful insight into gender differences between elite male and female wrestlers. At the time of this specific publication, matches could last as long as 7 minutes and 30 seconds.

Elite Chinese female wrestlers in the more recent Zi-Hong study (2013) reported similar findings across weight classes with 41.70 to 55.60 ml/kg/min VO2 max scores. Relative scores were not significantly different between 48, 55 and 63 kg weight classes, but the 72kg weight class was significantly lower.

Both gender sets of data were obtained using a treadmill protocol. However, this evaluative measure might be questionable being that wrestlers may or may not partake in running training sessions and therefore may not be familiar with that modality. When a cycle ergometer was employed with elite male wrestlers (Horswill,1992) reported peak oxygen uptake values of 45.4 – 64.0 ml/kg/min. No published data for elite females is available using a cycle ergometer.

In Zi-Hong’s study (2013), the Elite Chinese female wrestlers also completed a 3,200-meter time trial run. The average time for all weight classes was 14 minutes and 1 second. The 3,200 meter run times were not significantly different between the weight categories. No other data for female wrestlers is available using this field test.

Putting this into perspective with other populations, elite male and female wrestlers have peak oxygen uptake capacities that are average to above average compared with untrained and sprint trained individuals but are below average compared with the endurance athlete.

In reviewing studies comparing the peak oxygen uptake of successful and less successful wrestlers, it appears that oxygen uptake is not a major determinant of success. The Olympic and World Championship medalist wrestlers from China showed no consistent pattern of having the best score in the 3,200-meter run or Vo2 max treadmill test (Zi-Hong, 2013). Horswill et al. (1989) show that at three levels, Olympic, collegiate and scholastic, the peak oxygen consumption is not significantly different between successful and less successful counterparts.

Collectively, aerobic metabolism is an important fundamental pre-requisite to achieve good performance, but it may not be a major determinant of success in all weight categories and genders. However, this is a question that has yet to be clearly answered (Utter et al., 2002). In the 2010 Annual Review of Wrestling Research, top male wrestlers were noted to have VO2 scores over 60 ml/kg/min.

It is also important to note the contribution of central and peripheral fitness to peak oxygen uptake may vary between the upper and lower body. Specifically, peripheral fitness tends to make a larger contribution to peak oxygen uptake for arm cranking than does central fitness. Perhaps peripheral muscular endurance needs to be further and more formally investigated.

Concluding Statement Re: Characteristics

With the current duration of international matches and an emphasis on an aggressive style of wrestling that promotes high point scoring maneuvers in international competition, strength, anaerobic power, and anaerobic capacity are the dominant physical qualities of successful wrestlers (Yoon, 2002).

Collectively, the research indicates that no single physiological parameter in isolation determines elite wrestling performance. However, the strength and power values of Olympic and World Championship medalists are at the upper end of the parameter’s range whereas aerobic power may not separate Collegiate and National level from World (elite) level.

The Puzzle — The Interference Effect

Strength and Conditioning for wrestlers is a huge puzzle, especially when we factor in technical and tactical development, which can also be quite taxing on the athlete. Wrestling requires the development of several qualities simultaneously: Aerobic power, maximal strength, power, muscular endurance, and speed. The adaptations for resistance training, speed training, and endurance training are different and in many instances conflict. Thus, programming strategies run the risk of the interference effect.

Concurrent training, by definition, is “performing aerobic exercise within the same training program as resistance training “ (Bagley, 2016). Wilson (2012) defined it as “the inclusion of resistance training combined with aerobic exercise in a single program.” The “Interference Effect” which is the plausible result of concurrent training, is where adaptations from endurance exercise differ or even conflict with adaptations from strength and power exercise.

Numerous studies have concluded that it is difficult to concurrently develop strength, power, speed and aerobic fitness for several reasons including the tug of war of the both the Nervous and Endocrine systems during the process of adaptation. Several biological theories can help explain the incompatibility of all of these fitness qualities such as: Changes in motor unit recruitment, Residual fatigue, Specific adaptation in the muscles and the nervous system, and Hormonal alterations. This is by no means an exclusive list. What is important to mention here with respect to the research on concurrent training is this: All studies are subject to careful interpretation; the findings and practical application are always subject to the very pertinent question:

Who were the subjects and what conditions were present during the time of data collection?

Adaptation to exercise is directly related to the training stimulus an athlete is exposed to. This is the fundamental premise behind the SAID principle. This is a true, yet an incomplete statement. All biological systems are variable and influenced by a myriad of factors. In order to truly elucidate the effects of a training intervention, athletes must be monitored daily, and the coach must be responsive in his or her intervention, keeping the training objectives in mind without sacrificing the state of the human organism.

Conventional strength and conventional endurance modes of exercise training induce markedly different chronic adaptations when performed as a single modality. It is typical of strength-training programs to involve large muscle group exercises with high resistance and low repetition with the goal to improve the force and power output of skeletal muscle and neural signaling to the involved musculature. Chronic exposure to high-intensity strength training results in muscle cell hypertrophy via increases in protein synthesis and accretion of contractile proteins (Passelergue & Lac, 2012) and improvements in neural drive.

In comparison, exclusive endurance-training programs typically utilize low-resistance, high repetition exercises that involve large muscle groups and are cyclic and repetitive. Muscle tissue responds by degrading myofibrillar protein to optimize oxygen uptake kinetics (Passelergue & Lac, 2012). Chronic adaptations to endurance exercise include increases in aerobic enzyme activity, mitochondrial density, vascularization in the trained muscle bed and improved maximal oxygen uptake (Hunter et al., 1987).

It is, however, important to note that the two are not always mutually exclusive, even when performed on their own. Some forms of strength and endurance training programs may not reflect the above adaptations. Some strength training programs have produced very small, albeit significant increases in VO2 max as well as muscle endurance (Hickson, 1988) and some endurance programs have increased strength and muscle fiber size (Gollnick, 1973). It is not as cut and dry as it may seem.

Numerous studies have highlighted the consequences of the interference effect on maximal dynamic strength, speed running and maximal torque, especially at fast angular velocities (Robineau et al., 2014). Other investigations proposed that these impairments are largely debatable (Robineau et al., 2014). Several studies also highlight improvements in peak oxygen consumption and markers of aerobic capacity (Robineau et al., 2014).

Research, however, rarely reflects the normal training and competition schedules of elite wrestlers. Several studies reviewed in this topic area used untrained subjects, which are not a comparable population to wrestlers. The levels of speed, strength, and power, as well as training experience among highly trained wrestlers, far exceed that of the average recreationally active person.

“The real question lies in whether or not the interference effect has a universal phenomena or if it is very much context specific.”

Concurrent Training Research Review

Hickson began with the first concurrent training study in 1980. His intention was to “investigate how individuals adapt to a combination of strength and endurance training as compared to adaptations produced by either strength or endurance training separately.”

Hickson’s findings demonstrated that “simultaneously training for strength and endurance results in a reduced capacity to develop strength, but did not affect the magnitude of increase in VO2 max.” Delving deeper into the guts of his research included:

- Only using recreationally active subjects,

- Using subjects as old as 37 years,

- Strength training 5x/week,

- Endurance training 6 times per week,

- Concurrent training for 10 weeks straight.

- Both strength and endurance qualities were trained on the same day and only separated by 2 hours of rest.

- There was no indication in the methods of which quality was trained first.

Pre and post testing measures were valid and reliable but there were no measures of the force-velocity relationship in this study. Although Hickson’s works opened the investigative gates for this area of study, it is difficult to apply his research findings to highly trained athletes who require high levels of power to be successful at the world stage in their sport.

The reality is, combining methods of strength and power training with conditioning sessions is commonplace for a strength and conditioning coach. Much of the literature suggests that under concurrent training conditions, the amount of work that can be performed in each strength-training session could be negatively impacted by residual fatigue from prior endurance training. This may result in compromised strength improvements over the course of a training program.

The fatigue hypothesis it is actually quite difficult to interpret as the cause of such fatigue could be based on a variety of physiological factors such as hydrogen ion accumulation and subsequent blood pH change, depletion of muscle energy supply, neural fatigue, or structural damage to muscle fibers. This is beyond the scope of this article but should be acknowledged with respect to physiological impairments and timelines.

Sale’s work (1989), conducted over 20 weeks examined the long-term effects of variations of recovery periods between strength and aerobic training sessions on strength from both same-day and alternate-day concurrent training. Although the training programs were identical, alternate day training showed significantly greater improvements in maximal leg press strength than same-day training at both 10 and 20 weeks. Their findings suggest 24 hours of recovery following aerobic training (Sale, 1989).

Abernethy (1993) demonstrated that isokinetic strength was impaired for up to 4 hours following high-intensity aerobic interval training. It could be assumed that isotonic strength would be impaired for up to 4 hours as well (Abernethy, 1993). These findings suggest compromises in strength may last up to 8 hours post-aerobic training, which further supports a longer recovery period between sessions.

Other studies (Sporer and Wenger, 2003) provide more insight on residual fatigue from prior aerobic (endurance) training. Their results indicate aerobic training at a variety of durations and intensities negatively impacted both isotonic and isokinetic strength performance at both 30 minutes and 4 hours post-session (Sporer and Wenger, 2003). It was highlighted when recovery from aerobic exercise was increased to 8 hours, strength performance was not compromised (Sporer and Wenger, 2003). Maximal aerobic training appears to similarly affect strength performance as does submaximal aerobic training when equated for duration. Although aerobic training primarily recruits slow-twitch (ST) fibers, as the intensity of training increases, FT muscle fibers are recruited and taxed to a greater extent (Sporer and Wenger, 2003). It would be expected, then, that higher-intensity aerobic training would result in a greater amount of fatigue prior to strength training. However, no effect of type of aerobic training was shown (Sporer and Wenger, 2003). This provides the coach with a wide range of training intensities to prescribe when aerobic training must precede strength training (Sporer and Wenger, 2003).

Research conducted by Wilson et al. (2012) identified which prescriptive components of endurance training (Mode, Duration, Frequency) were detrimental to resistance training outcomes. A meta-analysis of 21 studies was conducted. As a large portion of the literature suggests, aerobic capacity was not inhibited with concurrent training as compared to endurance training alone (Wilson et al., 2012). Wilson’s meta-analysis focused on the training outcomes: strength, hypertrophy, and power. A study design criterion, such as the use of trained subjects, was not considered. However, some conclusions are worth discussing.

Wilson et al. (2012) found that modality (type of endurance stimulus, i.e., biking) takes first place on the interruption in strength and power adaptations. Decrements were seen in strength and hypertrophy when strength training was combined with running versus cycling (Wilson et al., 2012). It should be noted though that running resulted in a larger decline of fat mass (Wilson et al., 2012).

Interference effects were also primarily body part specific as decrements in strength and power were seen in lower body exercises versus upper body exercises after a lower-body dominant endurance activity was performed (Wilson et al. 2012). It could be hypothesized that upper-body endurance training could negatively impact upper body strength development.

Overall training volume accounted for a small portion of the interference effects (Wilson et al., 2012). Volume is typically defined as the total amount of work completed in a training session. For endurance training this is usually based on time at particular intensities. This meta-analysis also suggested that shorter-duration, high-intensity sprinting does not result in decrements in strength and power (Wilson et al., 2012). However, specific prescription examples were not given. The optimal amount of endurance volume, when trained concurrently with strength, appears to be less than 30 minutes per session, 3 times or less per week (Wilson et al., 2012).

Much of the research investigates concurrent training prescription on strength, hypertrophy and aerobic capacity outcomes. However, power, may, in fact, be the most susceptible quality. While Hakkinen et al. (2003) reported similar increases in maximum EMG activity in both concurrent trained and strength trained only individuals, increases in rate of force development and associated rapid neural activation of trained skeletal muscle were only seen in the strength trained individuals. It was suggested, “the addition of endurance training may have suppressed the improvement in rapid neural activation in those who trained concurrently” (2003).

Jones et al., (2015) also found inhibition of lower-body power development after 3 and 6 weeks of concurrent training when compared with strength training alone indicating that power phenotypes are more susceptible to interference than maximal strength indices. Counter-movement jumps, rate of force development and peak torques at high velocities were all negatively impacted as a result of combing strength and endurance training, yet maximal strength remained uninhibited (Jones et al.,. 2015).

However, these findings are not consistent with other research (O’Sullivan, 2013). O-Sullivan suggests that concurrent training in well-conditioned athletes may not attenuate neuromuscular adaptations to strength training. In fact, intelligent sequencing of training may be the key to allowing elite athletes to perform concurrent strength and endurance training without negative impacts on anaerobic power performance (Abernethy, 1993).

Programming Considerations for the Elite Freestyle Wrestler

- One must prioritize fitness components into the training plan, possibly emphasizing only one or two components in a mesocycle.

- Everything counts as training stress. It is best practice to monitor and quantify all training volume loads, including wrestling practices and S&C sessions.

- In terms of component order, perform strength work well before endurance work (24 hours is ideal). Do not program strength training after endurance training.

- If 2 components of fitness must be trained on the same day, separate strength training sessions and endurance sessions by a minimum of 8 hours.

- Do not program strength training after wrestling practice, unless it is only technical practice. In this case, rest a minimum of 4 hours.

- Directly after wrestling practice an athlete may perform low-intensity endurance training as a means of recovery.

- Avoid adding extra endurance sessions for the purpose of weight cutting. Instead, work with a Registered Dietician to achieve this goal.

- Select a modality of endurance exercise that closely resembles the DEMANDS of the sport to avoid occurrence of competing adaptations.

- Avoid long duration endurance exercise; Keep sessions under 30 minutes total training time.

- Endurance exercise should be performed no more than 3 times per week.

- Running might be a good modality for athletes seeking to lose bodyfat. However, it might be a poor choice for heavier athletes as it is high impact and has a large eccentric component associated with muscle injury and longer recovery timelines.

- Select endurance exercise where one can maintain a very high pace (work rate) to avoid loss of muscle mass, strength and power.

- Keep lower body lifting sessions to 2 days per week, separated by 48-72 hours.

- Create a split routine if endurance (conditioning sessions) cannot be programmed away from strength sessions. For example, perform explosive medicine ball throws, bench press and back exercises with a high-intensity cycling interval session on the same day.

- Be a flexible coach. At the end of the day, to be a great wrestler, one must wrestle. Although strength and conditioning does have a big role in the athlete’s development, it does not replace the valuable time spent on the mats.

- Work with wrestling coaches to train specific energy systems at practice in a more competitive and sport-specific environment. Work together to create the most ideal training schedule for your athlete.

Future Directions

Experienced coaches who work with highly trained strength-power athletes would question most of the practical application of the research on concurrent training to date as it has often been conducted on untrained subjects for too short of an intervention period. Thus, research findings will be more helpful when the subjects tested are trained and include technical and tactical training as part of their overall training plan. With experienced wrestlers, the use of RPE during both practice and matches combined with duration can give investigators good insight into total volume loads at wrestling practice. Different technical skills practiced by the wrestler elicit very different levels of muscular effort, so this must be considered in the overall training program. Practice conditions can be classified as high intensity or low intensity: Live go’s and match specific work to rest ratios are all high intensity. Technical, slower pace partner work might be considered low intensity. Heart rate data might not be helpful as a means to categorize intensity due to the nature of the work. If we consider sport-specific drills and practice settings as specific modalities of endurance training, we might be able to evaluate their impact on strength, speed and power outcomes.

Finally, a more holistic approach to adaptation must also be examined with mention of life stress levels, sleep patterns, nutrition practice, relaxation strategies and other important factors that can make or break the adaptation process. Research on concurrent training so far has ignored these seemingly outside factors and their impact on recovery. Although case study research is often frowned upon for lack of statistical significance, perhaps this is the new frontier in examining a more realistic study design and training outcomes.

Final Message

Understanding the demands of the sport of wrestling is of huge value to the strength & conditioning coach and sport scientist. The application of this knowledge must incorporate all dimensions of physiology, biomechanics and sport medicine with the combined intuition and coaching ability of the elite coach. A comprehensive review of fatigue models and Hans Selye’s works is a terrific place to begin general investigation of the process of adaptation. The study and dissection of training practice of sprinters, throwers, jumpers, gymnasts, weightlifters, GS lifters, rowers, swimmers and endurance athletes also helps one understand the training process. It is from studying these less chaotic or purist sports that one can begin to understand how the athlete may or may not adapt to a training program that involves the development of several physical qualities at once (Tsatsouline, Personal Communication, 2016).

“Sport science research does not provide all of the answers. We must maintain our senses and humanity in all that we do as coaches.” — Coach Bott

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

- ABERNETHY, P.J. Influence of acute endurance activity on isokinetic strength. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 7:141–146. 1993.

- ABERNETHY, P.J., AND B.M. QUIGLEY. Concurrent strength and endurance training of the elbow flexors. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 7:234–240. 1993.

- BAKER, D.G., AND NEWTON, R.U. Adaptations in upper-body maximal strength and power output resulting from long-term resistance training in experienced strength-power athletes. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 20 (3): 541-546, 2006.

- BARBAS, I ET AL. Physiological and performance adaptations of elite Greco-Roman wrestlers during a one-day tournament. European Journal of Applied Physiology 111: 1421-1436. 2011.

- BELL, G.J., S.R. PETERSEN, H. QUINNEY, AND H.A. WENGER. Sequencing of endurance and high-velocity strength training. International Journal of Sports Medicine 13:214–219. 1988.

- BELL, G.J., SYROTUIK, D. et al. Effect of concurrent strength and endurance training on skeletal muscle properties and hormones concentrations in humans. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 81: 418-427. 2000.

- CALLAN SD, et al. Physiological profiles of elite freestyle wrestlers. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 14(2): 162–169, 2000.

- CHILIBECK, P.D., SYROTUIK, D and BELL, G.J. The effect of concurrent strength and endurance training on quantitative estimates of subsarcolemmal and intermyofibrillar mitochondria. International Journal of Sports Medicine 23: 33-39. 2002.

- DOCHERTY, D., AND B. SPORER. A proposed model for examining the interference phenomenon between concurrent aerobic and strength training. Sports Medicine 30:385–394. 2000.

- DUDLEY, G.A., W.M. ABRAHAM, AND R.L. TERJUNG. Influence of exercise intensity and duration on biochemical adaptations in skeletal muscle. Journal of Applied Physiology 53:844–850. 1982.

- DUDLEY, G.A., AND R. DJAMIL. Incompatibility of endurance and strength training modes of exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology 53: 1446–1451. 1985.

- GARCIA-PALLERAS J et al. Physical fitness factors to predict male Olympic wrestling performance. European Journal of Applied Physiology 111: 1747–1758, 2011.

- GOLLNICK, P.D. Metabolism of substrates: energy substrate metabolism during exercise and as modified by training. Symposium: Metabolic and Nutritional Aspects of Physical Exercise. April 11, 1983.

- HAKKINEN, K., ALEN, M., KOMI, P.V. Neuromuscular, anaerobic and aerobic performance characteristics of elite power athletes. European Journal of Applied Physiology 53: 97-105. 1984.

- HAKKINEN K, ALEN M, KRAEMER W et al. Neuromuscular adaptations during concurrent strength and endurance training versus strength training. European Journal of Applied Physiology 89: 42-52. 2003.

- HENNESSEY, L.C., AND A.W.S. WATSON. The interference effects of training for strength and endurance simultaneously. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 8:12–19. 1994.

- HORSWILL C.A. Applied physiology of amateur wrestling. Sports Medicine 14(2). 114-143. 1992.

- HORSWILL C.A. SCOTT, J.R. ET AL. Physiological profile of elite junior wrestlers. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 59 (3). 257-261. 1988.

- HICKSON, R.C. Interference of strength development by simultaneously training for strength and endurance. European Journal of Applied Physiology 45:255–263. 1980.

- HUBNER-WOZNIAK, E. KOSMOL, A AND GAJEWSKI, J. Aerobic fitness of elite female and male wrestlers. Biology of Sport. Vol 26(4): 339-348. 2009.

- HUNTER, G. DEMMENT, R and MILLER, D. Development of strength and maximum oxygen uptake during simultaneous training for strength and endurance. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. 27 (3), 1987.

- KRAEMER WJ, FRY AC, et al. Physiological and performance responses to tournament wrestling. Med Science Sports Exercercise 33: 1367–1378, 2001.

- KRAEMER WJ, Vescovi JD, and Dixon P. The physiological basis of wrestling: Implications for conditioning programs. Strength & Conditioning Journal 26: 10–15, 2004.

- KRAEMER, W.J., J.F. PATTON, et al. Compatibility of high-intensity strength and endurance training on hormonal and skeletal muscle adaptations. Journal of Applied Physiology 78:976–989. 1995.

- LEVERITT, M., AND P.J. ABERNETHY. Acute effects of high-intensity endurance exercise on subsequent resistance activity. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 13:47–51. 1999.

- LEVERITT, M., P.J. ABERNETHY, B.K. BARRY, AND P.A. LOGAN. Concurrent strength and endurance training: A review. Sport Medicine 28:413–427. 1999.

- LEVERITT, M., H. MACLAUGHLIN, AND P.J. ABERNETHY. Changes in leg strength 8 and 32 hours after endurance exercise. Journal of Sport Science 18:865–871. 2000.

- MIRGHANI, S. ET AL. Influence of strength, endurance and concurrent training on the lipid profile and blood testosterone and cortisol response in young, male wrestlers. Baltic Journal of Health and Physical Activity. 6 (1) 7-16. 2014.

- MIRZAEI, B AND LOTFI, N. Physiological profile of a world wrestling champion. Presented at the 2010 Annual Review of Wrestling Research.

- MIRZAEI, B, CURBY, D ET AL. Physiological profile of elite Iranian junior freestyle wrestlers. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 23(8). 2339-2344, 2009.

- MIRZAEI, B. GHAFOURI, A. A physiological profile of Iranian senior Greco-Roman wrestlers. Journal of Sport Sciences. 3(5). 8. 2007.

- MURACH, K and BAGLEY, J. Skeletal muscle hypertrophy with concurrent exercise training: contrary evidence for an interference effect. Sports Medicine March 2016.

- O’SULLIVAN, D. Concurrent strength/power and endurance training of players in elite football codes: A brief review. Journal of Australian Strength & Conditioning. 21(1), 52, 2013.

- POPADIC, O.; GACESA JZ, et al. Maximal anaerobic power test in athletes of different sport disciplines. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 23 (3): 751-755, 2009.

- ROBINEAU et al. Specific training effects of concurrent aerobic and strength exercises depend on recovery duration. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 30(3), 672-683, 2014.

- SALE, D.G., J.D. MACDOUGALL, I. JACOBS, AND S. GARNER. Comparison of two regimens of concurrent strength and endurance training. Medical Science in Sports and Exercise 22 (3). 1989.

- SALE, D.G., J.D. MACDOUGALL, I. JACOBS, AND S. GARNER. Interaction between concurrent strength and endurance training. Journal of Applied Physiology 68:260–270. 1990.

- SHARRATT, M.T. ET AL. A physiological profile of elite Canadian freestyle wrestlers. Canadian Journal of Applied Sport Science 11(2): 100-105. 1986.

- SILVA, R. ET AL. Concurrent training with different aerobic exercises. International Journal of Sports Medicine 33: 627-634, 2012.

- SPORER B and WENGER, H. Effects of Aerobic Exercise on Strength Performance Following Various Periods of Recovery. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 2003, 17(4), 638–644. 2003.

- UTTER, A.C., M.H. STONE, H. O’BRYANT H, R. SUMINSKI, AND B. WARD. Sport-seasonal changes in body composition, strength, and power of college wrestlers. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 12:266–271. 1998.

- UTTER, A.C. et al. Physiological profile of an elite freestyle wrestler preparing for competition: a case study. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 16(2) 308-315. 2002.

- WILSON, J et al. Concurrent training: A meta-analysis examining interference of aerobic and resistance exercises. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 26 (8). 2293-2307. 2012.

- Yoon J. Physiological profiles of elite senior wrestlers. Sports Medicine 32: 225–233, 2002.

- ZI-HONG H, LIAN-SHI F et al. Physiological profiles of elite Chinese female wrestlers. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 27(9): 2374-2395. 2013.