Given the current circumstances, the “if” and “when” of return to many sports is uncertain at best. Coaches will soon be inundated with the tasks of getting athletes ready in a hurry, keeping them ready, and possibly presenting novel training options if training happens to be all they can do. For the coaches in the “when” stage, we know it is impossible to make up for the lost time. So how can we buttress our athletes for the rigors of sport in that short period?

Coaches must get their kids from 0 to 100 without breaking them while also answering the question: “How do we keep them ready for when the time comes?” For the coaches in the “if” stage, providing a smooth transition to the field, court, pitch, or pool is the order of the day. This may even turn into a longer period of time than we think, so having a training option we can cycle out of, vary, or temporarily return to will help break the monotony of the grind with general coverage and low cost to the system.

Enter a variation on an old classic—the med ball tempo and alternative versions.

[vimeo 451904674 w=800]

Video 1. Repetitions of wall throws followed by high skips and backpedals.

Sound developmental practice traditionally calls for implementing extensive, low-intensity work to precede high-intensity phases. I’m certainly not advocating running miles at a slow pace here; rather, I’m suggesting that applying sprint and power exercises in an extensive manner will provide a segue to repeat sprint/explosive ability without trading risk for reward.

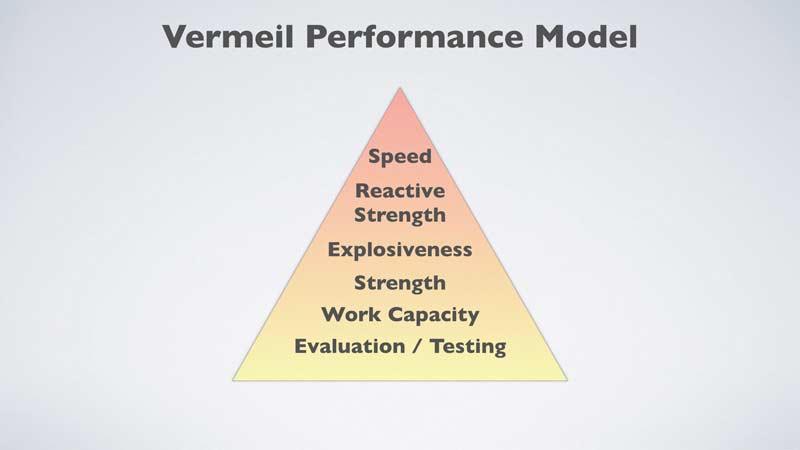

I’m suggesting that applying sprint and power exercises in an extensive manner will provide a segue to repeat sprint/explosive ability without trading risk for reward. Share on XTwo tools that can give you this “bang for your buck” are tempo running and extensive medicine ball throws—the marriage of which was seen in the work of a legendary coach who was conspicuously ignored in The Last Dance documentary (please excuse my public rant but someone must do it). Coach Al Vermeil used the med ball tempo (MBT) to develop work capacity, one of six components of his Hierarchy of Athletic Development pyramid and one that lies at its foundation.1

In its purest form, MBT combines tempo running with extensive med ball throwing.

A Variation on a Classic Theme

I’ll digress here a bit as I reminisce about my early years of training. I distinctly recall a harrowing experience doing MBT for the first time back in 2000 or so, when I undertook a one-month athletic training course. I registered for the course to learn how to formally perform and teach the weight lifts, but it also introduced me to other facets of training I had never done before.

One day, the coach in the course had me perform various throws against a wall followed by running the length of the training hall (maybe 20 yards down and back). After about four of these repetitions, I damn near collapsed! It was then that the coach, Lance Vermeil, said to me, “Dude, you’ve got to get into shape!” Years later I can now answer the question of where he got this from—Al’s damn med ball tempo!

Little did I know then that a version of this would become a staple in my programs for both competitive athletes and general fitness enthusiasts alike.

Sometimes space availability, orthopedic health, and athletic needs can become constraints for some athletes to optimally execute the running portion of the classic med ball tempo. Share on XThe classic med ball tempo combines submaximal throws with straight-ahead running to encompass the systemic development that should be part of every sound GPP modality. This combination allows for the systemic development of the cardiopulmonary system, multiplanar force absorption, and soft/connective tissue development of the lower limbs. Simple and effective enough, but sometimes space availability, orthopedic health, and athletic needs can become constraints for some athletes to optimally execute the running portion.

[vimeo 451907026 w=800]

Video 2. Medicine ball twist throws paired with a carioca run.

My variation on this theme comes in the form of substituting inefficient running patterns in place of straight-ahead running—which may be more effective in developmental phases for two reasons:

- These patterns allow for a low-impact, high-intensity option that trains the oft-neglected muscles of the lateral chain. The stabilizer muscles of the groin are trained with these atypical patterns such as shuffling, carioca, and crossover styles of running.2 For my athletes, the submaximal nature of these runs allows a safer introduction to faster, more intense cutting and change-of-direction drills. For our fitness enthusiasts, this option places less overall impact on the connective tissues while in turn training them for resiliency using undertrained patterns.

- These patterns are less efficient compared to regular running. For students of Dan John, inefficient exercise is “doing something that takes a lot of movement and heavy breathing but doesn’t get you far.” John also adds that this can be a weapon in improving body composition (along with dietary changes), as inefficient exercise will spike the heart rate given it is working harder to get from point A to point B.

Injury reduction combined with a proxy to better body composition seems like a winning combo for all types in my book!

What It Looks Like

I have affectionately dubbed this workout “Funky Throws”—and if you apply it with swimmers, like I do, you may see some funky things going on with the running too (but hey, they do business in the water). We rotate through six throws preceding three different running patterns.

Here is what the base template looks like on paper:

- Chest pass-high skip/back pedal (see video 1)

- OH throw-lateral shuffle

- Twist throw-carioca (see video 2)

- Scoop throw-high skip back pedal (see video 3)

- Front slam-lateral shuffle

- Hurricane slam-carioca

The throws are performed in extensive fashion against the wall, then the athletes take a trip 20 meters down and back. The high skip and back pedal combine opposing patterns, with the former going 20 meters down before returning with the back pedal. Make sure the shuffle and carioca are done facing the same direction to train both sides. We instruct athletes to complete each throw and run in successive fashion, continuously without any rest other than the transition time from ball to track and back. A “round” is the completion of six of the throw and corresponding run combos.

Programming and Variables

Progressions for this modality can have a short- or long-term scope. If you have some time to get in a solid aerobic block, a nine-week plot broken up into three-week phases will have you performing 10 throws for the first three weeks, 15 throws from weeks four to six, and 20 throws in the final three weeks. The shorter version will ramp up the throws from 10 reps on week one to 15 on week two and 20 on week three.

This is not to say you should scrap the program after three weeks, but rather manipulate other variables to increase the intensity. Initially, time the entirety of a round without letting your athlete know that you are timing them—let them dictate the pace and have them rest for approximately 1/2 to 3/4 of the work time. This work-to-rest ratio happens to fit within the parameter of aerobic dominance; more specifically, with work intervals of 3-5 minutes, leaving rest periods ranging from 1 1/2 to 2 1/2 minutes.3 This just so happens to fit the ranges I’ve timed my athletes for in their bout with “Funky Throws.”

If you decide to use the shorter plan, here are some variables you can manipulate to apply stress differently.

- Subtract 15-30 seconds from the rest time. On a 1:1/2 ratio, a five-minute set would normally rest for 2 1/2 minutes; just rest 2-2 1/4.

- Manipulate the load. A lighter ball will increase the power output by forcing the athlete to throw it faster, and a heavier ball will increase the force absorption coming back at them, probably a good option for contact athletes.

- Combine the metabolic runs with straight-ahead running. Follow each of the first three throws with the high skip/back pedal, shuffle, and carioca combo. Then follow the last three throws with straight-ahead tempo running—for longer, if possible. This will increase the overall distance within the same amount of work time: i.e., 240-360 meters per round.

- Chest pass-high skip/back pedal (20 meters down/20 meters back)

- OH throw-lateral shuffle (20 meters down/20 meters back)

- Twist throw-carioca (20 meters down/20 meters back)

- Scoop throw-run (40 meters down/40 meters back)

- Front slam-lateral shuffle (40 meters down/40 meters back)

- Hurricane slam-carioca (40 meters down/40 meters back)

Another option is to replace the runs altogether with a 100- to 200-meter distance on a row machine, if you are fortunate enough to have one. This has quickly become a favorite with my swimmers, as they sometimes don’t want to do road work.

[vimeo 451910053 w=800]

Video 3. Medicine ball scoop throws paired with high skips and backpedals.

If the weather isn’t cooperative, you can still maintain the integrity of the modality via an interval clock. Simply space out the throws and “runs” for a 30- to 45-second work period, resting the remainder of the minute. You can execute the inefficient runs with as little as a 5-yard space or instead employ a treadmill or a row machine. This will inevitably extend the total working time, but the difference in the intra-exercise work-to-rest ratio (between 30 on and 30 off and 45 on and 15 off) will maintain the aerobic energy system dominance.

The emphasis on work capacity—especially in the early stages of a career and a season—fits sound practice and is prevalent in Vermeil’s approach. The establishment and redevelopment of a work capacity reserve develops intra-session/contest and inter-session/contest recovery, effectively making the aerobic system omnipresent where the “work capacity reserve” becomes an essential weapon over the course of long seasons, overtime play, and maniacal sport coaching practices.5 The latter situation may be something fall sport athletes will have to contend with given sport coaches will be pressured to get their teams game ready.

These variations of the classic med ball tempo have served my athletes well and have allowed us to adapt to any logistical situation that comes our way. Share on XThe double whammy of resilience and fat loss makes the marriage of these concepts an ideal means to meet our athletes where they are and get them going to where they need to be. These variations of the classic med ball tempo have served my athletes well and have allowed us to adapt to any logistical situation that comes our way. The versatility of the med ball tempo and the “Funky Throws” has helped my clientele get in shape quickly, keep them in shape during competitive seasons, and provide unloading during more intense periods of training.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Twitter posted by @rugbystrengthcoach.

2. Van Dyke, Matt and Dietz, Cal. “Triphasic Training Metabolic Injury Prevention Running.”

3. John, Dan. “Fat Loss: The Hardest Thing to Do…And That’s All People Want to Do.” p. 40.

4. Fox, Edward L. and Mathews, Donald K. Interval Training: Conditioning for Sports and General Fitness. Saunders Co. 1974. Chart on p. 40.

5. Panariello, Robert. “Designing a Program Using Vermeil’s Hierarchy of Athletic Development.”