Really, it’s no secret—both the simplest and the most important recovery technique are one and the same: sleeping well. Which is fascinating, considering it’s still not clear why sleep has such a beneficial effect. One critical function activated during sleep has recently been identified: the “cleaning” of the brain and the elimination of waste that accumulates throughout the day, including toxins like beta-amyloid (which is involved in Alzheimer’s disease).

All of the stimuli from the day continually trigger neurons in the brain and, like any organ in the body that converts fuel into energy, this energy produces waste proteins that build up during waking hours and must be eliminated when we sleep. Recent research has shed new light on this process and may lead to a roadmap for preventing cognitive decline and degenerative diseases. During the night, our brain goes through several phases:

- From lighter sleep to deep, restful—almost unconscious—sleep, characterized by slower brain waves; to

- The rapid eye movement phase (REM sleep) where the brain becomes more active and we are the more likely to dream.

Most researchers have focused so far on the deep, non-REM phase of sleep, during which brain activity slows down and memory retention takes place. Recently, in the journal Science, a team of Boston-based researchers used non-invasive techniques on human subjects to demonstrate that the electrical activity of brain waves plays a role in this “cleaning” process.

Brain waves are produced by electrical impulses from masses of neurons that fire together in rhythm. Their activity is faster when we are awake and slows down when we are asleep. During non-REM sleep, neurons experience a synchronized decline in activity and throughout this “quiet period,” blood flows away from the brain as decreased activity means reduced oxygen requirement. As blood flows out of the brain, cerebrospinal fluid rushes into the vacated space and flushes toxins from the brain.

Brain waves are produced by electrical impulses from masses of neurons that fire together in rhythm. Share on XNeurons are busy when we are awake; they keep activating in unison and they need oxygen to do their job. Thus, the blood does not drain from the brain and there is no room for the cerebrospinal fluid to enter and remove the waste from all this activity. Understanding this discovery allows us to better grasp how sleep issues can impact an athlete’s performance beyond energy levels.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9056]

Clear the Beta-Amyloid!

First and foremost: the beta-amyloid is the enemy to be struck down!

If a player appears listless, responds to your encouragement with a pale imitation of Droopy, and exhibits declining cognitive performance, chances are that this protein has something to do with it. The good news is that supplementation with vitamin D3 and turmeric helps in the evacuation of this brain waste. If players appear more tired than normal, complain of an unhealthy relationship with Mr. Sandman, or are going through a period rich in decision and reflection (contract negotiation, change of club, recent paternity, etc.), it is advisable to recommend a compulsory daily intake of these two substances.

Vitamin D3 and turmeric helps in the evacuation of brain waste. Share on XVitamin D3 and turmeric can also be the subject of a collective supplementation strategy used to cope with a situation where the quality and quantity of sleep are undoubtedly compromised. This is the case during post-match trips that extend into the early hours of the morning, during scheduled evening competitions, or even during an intensive training camp where athletes are overworked.

Sleep Issues Are a Shared Responsibility

As a next step, the staff must take responsibility. Muscles aren’t all that benefit from night-time calm. The brain also needs its moment of peace. It is necessary for it to evacuate metabolic waste at the risk of being degraded. A player will not be able to assimilate the strategic instructions, nor reproduce the technical gestures of their position with an invariable quality, unless the daily byproducts of their cognitive activity have been naturally cleaned up by sleep.

If this “cleaning” has not been done properly due to poor or insufficient sleep, you will find them yawning during the video sessions and they will be lost in the weight training sessions. If you turn off the water in the locker room, the athlete will remain dirty and in an awkward position. Likewise, if you ask them to think and worry about this or that all the time, they won’t be able to let the blood flow out of their scalp and consent to the cerebrospinal fluid doing its job.

It’s easy to lecture athletes by pointing at a sleep hygiene infographic—oftentimes, we desperately attempt to generate positive changes in behaviors regarding sleep hygiene in our players with colorful charts and worrisome statistics. And oftentimes, we fail. Not because our athletes are bad students of sleep science, but because we do not recognize that we are a part of the problem, that the environment we created is conducive to poor sleep habits.

For instance, it is well documented that the further away from the bed a cell phone is kept at night, the more likely it is we will have a good sleep, either from taking away the urge to check Instagram notifications until late or from the potential negative effects of signaling waves. Still, many of us ask of our players to connect to fill out some kind of online wellness questionnaire immediately upon waking up, or worse to undertake a heart rate variability test before leaving bed. It is our demand that prevents them from adopting a behavior we praise.

It is our demand that prevents our athletes from adopting a behavior we praise. Share on XLikewise, educating athletes on how to set up the perfect bedroom—ideal temperatures, dark curtains, and expensive mattresses—is in vain when competition schedules and traveling strategies mean that a high number of nights will be spent in hotel rooms or on overnight flights and long bus trips. When we address the topic of better sleep using only “education” tools and programs, we not only fail to take responsibility for some of the poor habits developed by our athletes, we struggle to give actionable recommendations.

On many occasions, I found myself addressing a player reporting poor sleep with a totally unrealistic suggestion such as “avoid stress before bed.” Nobody ever purposely inflicts themselves with a good dose of stress before bed. But for those who come home to their families, a partner sharing their concerns or a young child who needs to be taken care of both present common sources of unavoidable evening stress.

Do not forget that athletes are humans first, and when they spend eight hours a day training and thinking about their sports, when will they have time for the vast amount of other concerns that populate an adult life? Relationships, finances, family, and—in some countries—trying to understand a new tax system? For those who stay awake late at night, lack of sleep becomes an obsession, a destructive fear.

Before condemning players for their nonchalance, their unprofessionalism, or their counterproductive habits when they have not had enough sleep, coaches must question themselves. When planning a field session from 6 p.m. to 8 p.m. or a team meeting at 6:30 a.m., consider if these will help the players recover better. Does bombarding the team’s WhatsApp group with schedule changes and various recommendations until late in the evening allow their brains to regenerate?

The same prescriptive effort that is provided during warm-ups or prehab exercises is required to assist the player in their quest for restful sleep. No doubt, investing in high-tech gadgets that sound “Silicon Valley” and made you feel like a real scientist in your last podcast is tempting. You may be thinking “If the player’s sleep can be recorded, then the problem can be assessed objectively.”

The same prescriptive effort that is provided during warm-ups or prehab exercises is required to assist the player in their quest for restful sleep. Share on XStop there!

If you are asking an athlete to wear a smart device every night, it is imperative that you know exactly how to interpret each variation and that you are prepared to draw up a plan of action for it.

An athlete with insomnia appreciates a report confirming their sleep deficit as much as an overweight player appreciates the morning weigh-in…when faced with a player who fails in their attempt to lose weight, what do you do? Do you make them download an application on their phone that weighs them in real time? Do you recommend that they “eat less” and “be more careful”? No (unless you really don’t like them).

As a conscientious professional, you are more likely to refer them to a nutritionist, a specialist who can work with them for the long term. So why should the player who cannot give in to sleep’s call be treated any differently? The gadget approach is expensive, and resources would be better spent on consultations with a sleep specialist.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=11132]

Be Open to Changing Your View on Optimizing Sleep

Sometimes, a few corrections are enough; other times you have to review the copy entirely. As elite sport coaches, we must first identify the goal, the objective. The next step is to determine if the athlete, player, or squad is open to the coaching philosophy, and to define the best approach to get our messages across. Adopting a new attitude always goes through three phases:

- It starts with an openness to change which, little by little, turns into a desire to change behaviors.

- Then comes the need to change behaviors, radical and stubborn.

- Finally, the new way takes hold and becomes normal over time.

So, it’s not impossible to demystify sleep—to redefine it and adopt practical and achievable measures to fully reveal this natural process of human recovery which, even today, remains under-taught and underestimated. A change in the way we approach sleep must take into account three essential facts:

- The circadian rhythm.

- The chronotype.

- The fact that the traditional “eight hours of consecutive sleep” is simply unnatural.

Planning Training with Respect to Circadian Rhythms

The circadian rhythm is a 24-hour cycle which controls our biological and physiological functions. When daylight enters our eyelids in the morning—the first phase of our human day—the brain begins to produce serotonin, which reactivates mood, motivation, appetite, gut, and bladder. As the afternoon progresses, the light levels drop, and the brain begins to produce melatonin. This hormone is also produced if too little natural light enters the eye for several hours, causing a feeling of drowsiness and a lack of energy and motivation.

The circadian rhythm is a 24-hour cycle which controls our biological and physiological functions. Share on XTherefore, to stay alert and energetic during the day—and then calm and serene at bedtime—it is essential to respect this circadian rhythm. The source of the sleep disturbance may not be within minutes of falling asleep. It may not be a question of “sleep hygiene,” or some absurd addiction to video games. It is conceivable that the source of the problem is the schedule imposed upon the player.

For many athletes, the light exposure is too low during the first two phases of the 24-hour cycle (morning and afternoon). If you have basketball players playing indoors, the challenge is obvious. But for those who work in team sports played outdoors, it is necessary to review how training sessions are scheduled.

Perhaps on a typical day, the morning is spent indoors. Monitoring routine, breakfast, video session, weight training…the work done behind the curtains. Or is it perhaps the afternoon that is devoted to these activities? In any case, does the weight room have large openings letting daylight in abundantly? If the answer is no, it is highly likely that this type of schedule, under such conditions, disturbs the circadian rhythm of a majority of players, some of whom are not recovering.

Perhaps the complaints related to sleep are characteristic of the winter periods that your team goes through. With the reduction in natural light, the spectacle of field training sessions are performed only under artificial spotlights or are planned too early or too late in the day. To avoid disturbing the circadian rhythm, it is necessary to give the player the opportunity to spend time outdoors, in natural light, frequently, from the start of the day until the end. Ensuring a healthy circadian rhythm is about adapting to the seasons.

Respecting this natural rhythm also means providing players with a stable environment. When you have several groups, you tend to switch them over during the week. One group starting earlier than the other one day and vice-versa the next day. While this practice saves you from the anger of some, especially player union representatives, and seems like the right compromise, it may not be the most optimal in the long run, as it forces the circadian rhythm of players to shift in an attempt to adapt to daily changes.

Chronotypes and Performances

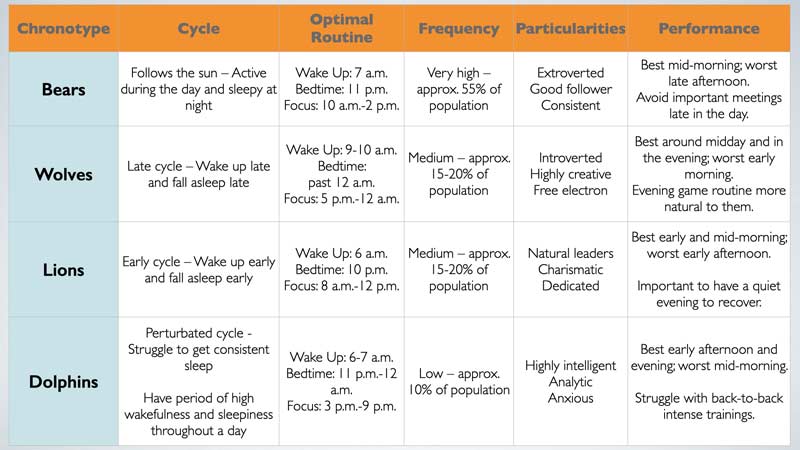

The concept of chronotype sounds sophisticated, but this is actually just a term for whether you are more of a night owl or an early riser. In zoology, the word chronotype refers to the time (“chrono”) of sleep and the regular activities of an animal. It is important to note that the chronotype has an implication beyond the time of getting up and going to bed: it is the body’s natural “timeline” for the various primary activities of a normal day (such as eating and sleeping) and also determines the best times for exercise, reflection, and rest.

Chronotypes have a genetic basis and are linked specifically to a gene, PER3. Early birds have longer PER3 genes, while night owls have shorter genes. Early risers and night owls are the most notable chronotypes because they are easy to contrast. However, they are not the only ones. Some researchers consider there to be four main chronotypes.

Chronotypes have a genetic basis and are linked specifically to a gene, PER3. Share on X

The type of chronotype impacts the level of activity and vigilance during periods of wakefulness. It affects body temperature, cortisol levels, and even blood pressure. For example, “lions”—morning people—experience a peak in body temperature earlier than night owls. This may have an implication on the necessary warm-up and activation time. If the training session is in the morning, the “wolves” will need a more intense warm-up than the “lions” in order to increase their muscle temperature and achieve sufficient cognitive activation. On the other hand, if the session is scheduled for the end of the day, the roles are reversed.

For most chronotypes, cortisol levels are at their highest in the morning, usually around 9 a.m. Cortisol begins to increase gradually in the second half of the night during sleep, then its production is accelerated upon awakening, before peaking one to two hours after waking up. From then on, it gradually declines throughout the day, reaching its lowest levels around midnight. In this way, cortisol plays a vital role in sleep-wake cycles: by stimulating wakefulness in the morning and continuing to support alertness throughout the day, while gradually decreasing to allow the body to produce other molecules and hormones, in particular adenosine and melatonin, which are involved in preparation for sleep.

However, the athlete’s life is punctuated by periods of significant physical stress (training sessions, matches, etc.) and much-needed rest periods. Each intense session causes an increase in the production of cortisol, which disrupts the cycle described above.

For chronotypes such as “bears” and “lions,” an intense morning workout is perfect as their cortisol levels are already high, and a more recovery-oriented end of the day perfectly accompanies the cortisol-melatonin transition. But for “wolves” and “dolphins,” whose cortisol production is delayed, the ideal timing of training and recovery periods is different. Some players with these types of profiles may have cortisol levels at their highest during the night and lowest in the morning. A workout placed in the middle of the morning then becomes problematic, because it keeps the level of cortisol high when it is supposed to be low. If this is repeated, an imbalance in the testosterone to cortisol ratio can occur, with all the complications that entails.

Knowing a player’s chronotype is informative and can help optimize training timing. However, in the context of team sports, individualizing the session schedules according to the profile of each athlete is science fiction. To meet the strategic and technical ambitions of a team, you have to bring together all the players every day at the same time.

Fortunately, it’s a safe bet that 80% of your workforce is made up of “bears” and “lions” who easily adapt to the classic programs offered (day that starts early; workouts in the middle of the morning; mid-morning and afternoon video/meeting; and preparation/recovery in the early morning, early afternoon, and end of the day). It is the remaining 20% which represents a decisive challenge.

Fortunately, it's a safe bet that 80% of your workforce is made up of “bears” and “lions” who easily adapt to the classic programs offered. Share on XA first strategic option could be to pull this small group of “wolves” and “dolphins” towards the others—to try to rectify their cycles so that they gradually turn into “bears” and “lions.” Specific light therapy sessions or the consumption of melatonin could help change their bedtime. Bad luck, however; the chronotype is genetically determined, and even if the professional and social rhythm adopted can have an impact on the cycle preferably followed, a radical change is not “trainable,” and the various tricks put in place do not guarantee the desired effect.

Exhausting yourself trying to adapt the player to the schedule by changing their chronotype will not be the most profitable strategy. Rather, it will be about adapting parts of the schedule to the player’s chronotype. Of course, juggling training schedules and threatening the smooth running of group sessions is out of the question. But, a typical day for a professional athlete is also made up of individual, varied, and flexible activities.

Individual meetings with coaches, media obligations, and other internal requests (administrative tasks, promotions, etc.) are within the scope of individualization based on the chronotype. The obligations that a player must meet during the day can be ranked from the most important to the least important, from the most cognitively demanding to the least demanding. Once this hierarchy has been established, it is sufficient to schedule the most serious activity during the period of peak productivity dictated by the corresponding chronotype, and to fit the others into the periods of lower performance.

With a “lion,” for example, a meeting with the manager to discuss strategy will preferably be held early in the morning, while smiling at the sponsors will be a perfect activity to accompany their lunch digestion. Inviting a “dolphin” to an important meeting at 7 a.m. will not do the athlete any favors—but around 1 p.m., when many of their teammates will be gathered around a video game or will be snoring peacefully away from prying eyes on a stolen yoga mat, the “dolphin” will be happy to be there and be part of a detailed conversation.

It is also possible to group the players by chronotypes, instead of the categorization by position generally applied, in order to determine their recovery and treatment slots. On the weekly rest day, why force a “wolf” to go to the training center for a massage at 8 a.m.? As for the “lions,” don’t ask them to make themselves available for treatment at 6 p.m., they are already longing for the comfort of a TV set. During a normal training day, the complicated chronotypes—“dolphin” and “wolf”—may present an imbalance in their cortisol production and require special post-workout attention. If places are limited, they should be granted priority access to the sauna, massages, and nutritionist.

Few teams bother to test their squad and categorize their players by chronotype; in the long term, however, if we multiply by the number of training days in a season, a small improvement in individual performances of even 1% due to an alignment of the proposed schedule and the chronotypes will make a difference.

Polyphasic Sleep: A Better Approach

Eight hours of solid, continuous, uninterrupted sleep—this is the goal we set for our athletes, the gold medal of recovery that everyone strives for every nightfall. A shower of infographics on the consequences of lack of sleep on sports performance, and the heavy incentives of coaches and the media, put night’s sleep on a pedestal and make it a major issue. When the player fails to score 8 or 10 hours of eclipse, they end up finding themselves to be tired, frustrated, and anxious in the morning. But the idea that we need to sleep in one uninterrupted block is not necessarily driven by biology. There’s a forgotten fact: we haven’t always had this approach to sleep.

The idea that we need to sleep in one uninterrupted block is not necessarily driven by biology. Share on XWestern European writers of the pre-industrial times refer to the two sleep intervals as if the prospect of waking up in the middle of the night was quite familiar to their contemporaries and therefore required no elaboration. During pre-industrial times, going to bed when the sun finally goes down, waking up in the middle of the night for a few hours, and then sleeping again until dawn was normal behavior, the most common mode of sleep.

Then comes the time of the industrial revolution: as electric lighting grows, people are breaking free from the limitations imposed by natural light cycles, and with it references to a “second sleep” begin to disappear. Nonetheless, studies suggest that humans tend towards biphasic sleep if given the opportunity. In the 1990s, psychiatrist Thomas Wehr showed that when people are exposed to 14 hours of darkness, not eight, they gradually shift to a two-phase sleep pattern: two four-hour blocks with a space in between.

Moreover, we find two-step sleep habits in many cultures—perhaps you have already tried the “siesta,” a practice dear to our Spanish friends? Or, have you already had the unfortunate experience of finding yourself waiting outside the doors of a Provencal post office, which close from 12 p.m. to 4 p.m.?

Sleeping in one block is considered the healthy norm, and problems arise when it is expected to always be a perfect eight-hour period of blissful nothingness. Many believe that healthy sleep is a deep valley of unconsciousness that runs throughout the time you are in bed, but the reality is more complex. Instead, we go through periods of light and deep sleep every 90 minutes or so. Sleep is characterized by its multiple phases, which are repeated in successive cycles clearly distinct from each other and separated by periods of wakefulness. Far from an extensive and monotonous process that would justify a solely monophasic approach.

Faced with this practice of monophasic sleep, biphasic sleep is not the only alternative option. Polyphasic sleep is known to researchers as a variant based on multiple blocks of sleep, with varying and shortened durations. Sadly, the polyphasic approach to sleep is now almost taboo after enjoying a period of superficial stardom and becoming the plaything of a generation hungry for over-productivity. Blame it on Uberman’s sleep program, whose goal was to gain waking hours by sleeping a total of just three hours in six portions evenly distributed throughout the day, which was supposed to compress the physiologically less-important stages of sleep and regulate the stages vital for mental health upward in a homeostatic manner.

The idea that one can transform into a superman by depriving oneself of sleep is absurd, as it comes into dissonance with the empirical reality observed by anyone who has tried to perform during an episode of insomnia! But asking players to sleep 8-10 hours in a row is just as unnatural and restrictive as requiring them to sleep 30 minutes every 4 hours. Every athlete is different. Some people need less sleep than others. Some are free to go about their sleep-wake cycles as they see fit, while others are forced to imitate the rhythm imposed by their newborn baby. Where one may live in perfect circadian harmony with their other half, another may struggle and compromise with a family of varied chronotypes.

The reality is, you can’t always finish on time, win every duel, and be flawless in every practice. The players know that. When they suffer a setback or underperform, they are masters of bouncing back. They are endowed with the wisdom to compensate. And what keeps them going through tough times is the opportunity to do better the next session.

The reality is, you can't always finish on time, win every duel, and be flawless in every practice. Share on XHowever, with a monophasic approach to sleep, the athlete in distress is deprived of a second chance. After a bad night’s sleep, the next one is already deemed critical. In season, this gaping hole cannot be filled in time to ensure peak performance in the next game, and in pre-season it makes the toil of the following days even more thankless. And after eight hours of imperative recovery stolen by a finicky nervous system, an impeccable eight-hour sleep appears as the sole way to re-establish balance.

Two sleepless nights, and suddenly the pressure surrounding the next twilight is immense. This performance urgency, night after night, creates unbearable psychological stress in those whose sleep is disturbed. This vicious cycle is not inevitable, however. Remember, the need to consolidate a single block of sleep is unfounded.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=11130]

Instead of tending to a single, crucial period, a multi-phased approach allows for a salutary freedom: taking the necessary time elsewhere in the day to relieve the pressure of having to sleep at night. Because sleep works in 90-minute cycles (not 8-hour or 10-hour cycles), the expectation of a full night should be replaced by the ability to intelligently manipulate multiple 90-minute cycles. Thus, in order to ensure sufficient recovery, the stake for the player is no longer to sleep eight hours per night, but to accumulate a minimum of five cycles of 90 minutes per 24-hour period.

Obviously, the majority of these cycles will preferably occur at night, firstly because it is naturally dictated by the circadian rhythm, and secondly because the opportunities are more plentiful after the training center has closed its doors. With this method, athletes are able to plan their five sleep cycles in line with their program for the next 24 hours—and in the event that an unexpected event disrupts the progress of a cycle, it can be transferred to the next 24-hour period.

The organization of a typical week in team sports has the particularity of exposing the actors to a true roller coaster. Some days of the week start shortly after dawn and unfold like a frenzied race against time—sometimes with up to four training session, meeting, preparation, recovery, and video time slots. Other days, when time flows more slowly and the mood is peaceful, are reserved for recovery.

On match days, the pressure is tangible; it knots the stomachs, galvanizes the energies, and very often takes away any hope of a serene evening. The post-match days are very different: the physical and psychological integrity of the players must be restored. Fatigue is present in all movements, and comfort is sought from loved ones around a well-stocked plate or by means of a gentle recovery protocol.

On match days, the pressure is tangible; it knots the stomachs, galvanizes the energies, and very often takes away any hope of a serene evening. Share on XDuring these weeks, days of excessive agitation and absolute or relative calm alternate, and some do not allow five cycles of sleep. Physical exhaustion costs cycles. The apprehension and excitement at the approach of an expected or feared confrontation costs cycles. Worst of all, evening games put the player’s nervous system in a state of turmoil, cause elevated cortisol levels, can introduce disturbing physical pain, and may keep the athlete’s mind busy replaying the game again and again instead of counting sheep.

Then, there are the late events to which the player is sometimes invited: dinner with the club’s partners, promotional operations, media appearances with a sponsor—these too are cycle eaters. On the other side of the equation, typical weeks have their fair share of opportunities to catch up on lost sleep. Recovery days can be filled with missing cycles, and some training days may have a late start, premature end, or periods of downtime: all opportunities to sneak in a missed sleep cycle. The calculation is simple: five cycles of 90 minutes equals 7.5 hours per 24 hours; five cycles multiplied by seven days gives a total of 35 cycles per week to reach. Shortened nights can be balanced with naps, late mornings, or early evenings.

Finally, in order to avoid over-distracting the circadian rhythm with the use of polyphasic sleep, it is important to adhere to a stable schedule for getting up and going to bed. If the whole week the player wakes up at 6 a.m. and wants to accumulate a few additional cycles on the weekend, just reprogram the alarm for another 90-minute cycle to go off at 7:30 a.m. And why not reprogram it again for an additional cycle?

In the opposite case, where the time to wake up is brought forward for an exceptional reason (travel, meetings, change of training schedule, etc.), it is recommended to wake up a complete cycle earlier. Continuing with the example above, if the player has to get to the training center 30 minutes early, then they should set their alarm for 4:30 a.m. instead of 6:00 a.m. In debt for a full cycle, they can repay it at their convenience.

It is largely up to the coaches to deliver their players a more precise and more educated message on sleep. Forcing them into a system that has no regard for their chronotype does not contribute to optimal performance. Refusing to prioritize circadian rhythms when setting a schedule does not contribute to optimal performance. And, above all, preaching for monophasic sleep in an environment like ours does not contribute to optimal performance.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

T.A. Wehr. “In short photoperiods, Human sleep is biphasic,” Journal of Sleep Research, June 1992.

N.E. Fultz et al. “Coupled electrophysiological, hemodynamic, and cerebrospinal fluid oscillations in human sleep,” Science, 2019.

Breus. “The Power of When: Discover Your Chronotype–and the Best Time to Eat Lunch, Ask for a Raise, Have Sex, Write a Novel, Take Your Meds, and More.” 2016.