Sitting in the bleachers behind the bench, bundled up between our team physiotherapist and nutritionist, I tightly squeezed their hands in mine. With the match level at a 2-2 in the 89th minute, our team had drawn a last-second penalty kick. Our 21-year-old striker, one of the league’s top goal scorers (and with both goals in this match to his name as well), adjusted the ball in his hands, settled it on the spot, and took three large steps back.

As we waited for the whistle, the goalkeeper bounced up and down dramatically on his line and the shooter’s eyes shifted just barely from the keeper to the left corner flag. I held my breath as the whistle rang out, silence falling over every spectator in the freezing stadium.

The young striker accelerated forward, striking the ball to the left side of the goal.

Wide left. Not even a save—simply a miss.

He hung his head, standing frozen in the middle of the box. As the other team celebrated their great fortune, a few players ran up to pat our forward’s back and encourage him. From afar, I could see his head shaking in disbelief.

I waited in the hallway outside the locker rooms for the last of the players to debrief and hit the showers. As he passed me, he avoided my eyes and dropped his head. “I bombed,” he grunted in no particular direction. I followed him toward the bus.

“What ran through your mind?” I asked, neither confirming nor denying his seemingly obvious but self-deprecating statement.

“Nothin’,” he huffed. “Said I already put up two. Add one more and make it a ‘hatty.’ Get the win.”

I nodded and shrugged. “What was the difference between the two goals in the run of play and the penalty?”

“Penalty isn’t run of play,” the young forward sighed, shaking his head. “Everyone’s watching. My parents were here. The national team scout was here too; saw him during warm-ups… I really wanted that hat trick.”

“What did you feel and where?” I asked, trying to gather more information about what exactly went on in the seconds before the penalty. “Was it distraction, confidence, stress… something else?”

He shrugged this time. “Nah,” he said as we dropped our bags in the luggage compartment under the bus. “Just thought, oh wow, this is a really big moment. Heart was beatin’ real fast and felt kinda tingly all over… like it was a big deal, y’know?” He smirked as we loaded ourselves into the bus, mounting his cool demeanor again. “Whatever. It’s done.”

Preparation and Performance

The world of performance sport is erratic at best, with its captivating highs and lows. Incredible feats of human achievement occur just as often and just as quickly as devastatingly poor performances. With the inherent instability of the sport world, stress and pressure are an inevitable experience for athletes, coaches, parents, and team staff alike. As such, it is important to understand and prepare for these occurrences, so as to limit their impact on performance when it truly matters.

Stress and pressure are an inevitable experience. It is important to understand & prepare for these occurrences to limit their impact on performance when it truly matters, says @thejulialion. Share on XMental preparation is as equally relevant and realistic as physical preparation training, which every athlete (and coach) is familiar with leading up to competition. As a psychophysiologist—or, more simply, a “sport psychology researcher” or “brain-body connection expert”—I teach performers how to manage their stress using a three-phase plan of mental skills training.

Before diving into the mental training portion of this blueprint, it is important to define the term “stress” and then understand how the body’s built-in stress management system works.

Stress, the Brain, and the Body

“What is stress?” has been the topic of some many thousands of research articles, most of which lead to further questions of what stimulates stress in the first place, why we humans most often frame it as an inherently negative experience, and whether there is a distinction between physical and psychological stress.

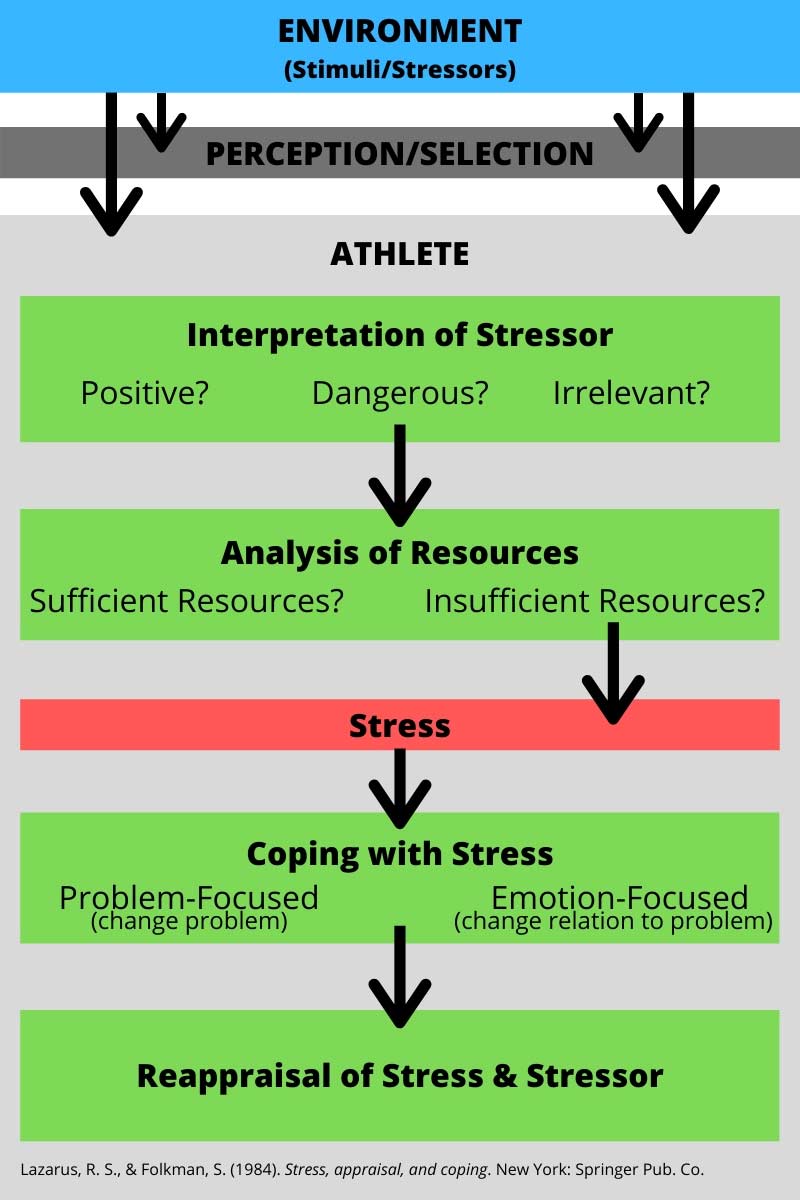

Dr. Richard Lazarus (1984) famously defined stress as a relationship “between the person and the environment that is appraised by the person as taxing,” “exceeding resources,” and potentially “endangering his or her well-being.”

This definition expands upon earlier research, which framed stress as “a response to any demand placed on the body.”This assumed that everything in life is a stressor and that stress was an answer to “any vigorous, extreme, or unusual stimulation, which, being a threat, causes significant change in behavior”—an interpretation that relies too heavily on an inherently negative reaction (Seyle, 1980; Miller, 1953).

What the human body tells us about stress, though, is that it is neutral.

When the brain and body first receive a new stimulus from the environment, the brain interprets this new stressor and tells the body how to react accordingly.

The brain asks: “Is this environmental stimulus positive? Is it negative? Is it irrelevant? Is there a potential danger nearby? Should we run?”

Let me frame this in the perspective of an athlete—any competitor can attest to how different performance environments are compared to training. For some players, the presence of spectators (which can include parents and scouts), the pressure of achieving their goals, and other environmental stimuli can be appraised as “dangerous” and begin a stress reaction, disrupting their focus during performance. This can happen even if the athlete is proficient in this skill and capable of perfect execution in training. Other athletes thrive under these conditions, using the “hype” as a driver for their performance and experience skill enhancement. And, in the same environment, another competitor may appraise these new situational stressors as “irrelevant” and have no skill disruption at all.

Compared to training conditions, competitive scenarios are just different, and naturally high-arousal athletes who suffer under pressure need to train for these changes.

Compared to training conditions, competitive scenarios are just different, and naturally high-arousal athletes who suffer under pressure need to train for these changes, says @thejulialion. Share on XSo, what exactly happens when the brain receives and appraises the stressor? Depending on how the brain perceives the stimulus, it instructs the body how to respond through the autonomic nervous system (ANS), which controls all of the body’s involuntary functions, like breathing and digestion. Its two branches, the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems, play primary roles in stimulating and inhibiting the stress response.

If a stressor is appraised as negative or threatening, even potentially, the sympathetic nervous system (also known as the “fight or flight response”) is activated. This can be thought of as the body’s gas pedal.

Through a series of complicated brain activity, the hormonal system releases a slew of hormones, namely adrenaline and cortisol, which heighten the body’s senses. The heart rate increases. The body’s attention is diverted from unnecessary systems, like the digestive and reproductive systems, temporarily slowing these processes down. Energy may surge at first, possibly resulting in jitters or stomach discomfort. Arousal is high. This is the built-in survival mode.

As you can imagine, this state is not optimal for peak performance in most sports. A golfer, sprinter, soccer player taking a penalty kick, or gymnast likely cannot perform well under these conditions, because the demands of their sport are specific and require accuracy.

However, there is another branch of the body’s build-in stress management circuitry, called the parasympathetic nervous system, which is responsible for regaining and maintaining homeostasis. You should consider this the body’s brake pedal.

This division of the system essentially inhibits the stress response created by the sympathetic nervous system by allowing the body to relax its muscles, decrease its heart rate, and reinitiate a focus on the nonessential systems such as digestion. The body is low in physiological arousal and thus able to continue its recovery processes. This is the built-in regeneration mode.

Is a completely relaxed parasympathetic state optimal for athletic performance?

Probably not. Very low levels of arousal might be preferred in some sports, such as darts or shooting sports, which only require very fine motor skills. Sports requiring physical fitness, especially in speed, power, and endurance sports, are less compatible with a low-arousal state. The body is required to perform at its maximum capacity for a duration of time; activating the full recovery mode is not possible!

Every athlete has an optimal level of arousal for their peak performance in their sport—some players thrive on the “hype” and need to psych themselves out to a high level of arousal before competing, while others need to calm themselves down from their naturally heightened arousal state (again, perception of threat and thus, stress). It is important that every athlete naturally identifies and can regulate themselves into this zone.

The process of identifying optimal zones for performance and the complete workings of the ANS and its branches are grounds for another article. In the following sections, I will present methods of teaching stress management to these naturally high-stress athletes.

The Competition-Stress Compromise

To begin addressing stress in sport, we must accept that mental and physical arousal (the feeling of stress in the body) is simply part of being a competitor.

As tennis icon Billie Jean King proclaimed, “pressure is a privilege.” The very presence of pressure, of competitive stress, means that an athlete has something important on the line: there is something to lose, but also something to gain. The investment of time, energy, dreams, and (in many cases) money is high. This is an experience that not every athlete, and certainly not every human being, gets to know or feel. It is specific and special.

Once athletes have accepted the presence (and privilege) of pressure, it is time to reckon with competitive stress in an individualized way in order to strike an optimal, replicable balance of “low arousal” and “over-arousal” in performance.

It is here that we introduce the three-phase blueprint for athlete stress management: preparation, maintenance, and damage control

Preparation

Athletes spend a lot of time physically preparing for what is often a very short competition.

Marathoners clock double-digit hours of training in the two weeks before a race. Soccer players pull two-a-days for a 90- to 120-minute match. Sprinters put in weight room and track sessions for events lasting seven seconds to two minutes.

Why? Because, in theory, the best-prepared athletes and teams usually win.

Athletes who are prone to becoming distracted—or even paralyzed—by their stress in competition may report a spiked heart rate and/or lack of concentration, appear lost, or simply underperform in competition as opposed to their normal training output. This requirement for preparation also applies to their mental training and strategies for managing stress.

Here are the facts of the matter:

- It’s often easier to prevent stress, and thus the distracting response, from happening in the first place, rather than to deal with it once it’s arrived.

- No athletes, especially stress-prone ones, can outwork a lack of preparation when it’s time to perform.

For athletes who struggle with performance pressure, staying ahead of the game—as much as is humanly possible without causing its own kind of perfectionistic stress—separates high performers from the casual, spontaneous types.

Physical training is a form of preparation. As every coach knows, very rarely can athletes out-perform a lack of fitness. Appropriate physical and mental fitness are as essential to peak athletic performance as oxygen is to human life. Skills, tactics, and technique have to be drilled in advance in order to achieve automated execution, which is less distracting and tiresome than non-automatic skills.

If players put the time, effort, sweat, and tears into their physical and mental training in advance, they can enter a performance situation confident in the execution of their skills, says @thejulialion. Share on XIf players put the time, effort, sweat, and tears into their physical and mental training in advance, it breeds confidence. They can enter a performance situation confident that they are physically and mentally prepared to execute their skills at that time. Coaches must encourage athletes to trust that training and the process.

Planning is also a key factor in mitigating stress in advance. When the time for performance comes, making decisions and handling difficult, cognitively tiring situations wastes mental real estate that should be entirely focused on performing. Encourage athletes to eliminate as many decisions and as much stress as possible in advance. This includes gathering necessary information, packing, planning, asking the right questions, and implementing pre-performance routines as long as possible before “go time,” so that 100% of their focus can be on performing.

The use of mental imagery is a helpful tool in the preparatory phase of a competition. Using their imagination and all five senses, an athlete can create a detailed image in their mind of peak performance: how they look, feel, and experience being in a flow state and performing optimally, even under the glare of lights and an audience and surrounded by noise. Imagery allows athletes to familiarize their brains with potentially new and stressful stimuli in advance of “go time” with the goal of mitigating the perception of threat and sympathetic stress response during competition. When it is time to perform, the brain and body should both say, “I’ve been here before—we’re good.”

Likewise, a solid pre-performance routine can help athletes focus in as the countdown to performance draws to an end. This may be the playlist they listen to, the order of the warm-up, the statements and affirmations they repeat to themselves, a pre-game mindfulness meditation, or the order in which they dress. This ritual or routine assists with concentration by taking away the distractions before a match and the number of decisions athletes have to make, and tells the brain, “Hey, we’re prepared for whatever comes our way. It’s ‘go time.’”

Maintenance

When stressful situations do inevitably occur—even when everyone involved has done their best to prepare—it is just as important for athletes to have tools in their belt to handle and minimize the stress response as it comes.

This is a skill called “coping.” Whether purposeful or not, everyone has developed an intuitive set of coping mechanisms, and they are often positive and helpful. Sometimes, however, they are not beneficial to performance (and, in fact, can distract from or decrease performance).

Thus, it is critical to help athletes develop purposeful, positive coping mechanisms around competitive stress. Like all skills, it takes lots of practice for this to become automatic.

It is critical to help athletes develop purposeful, positive coping mechanisms around competitive stress. Like all skills, it takes lots of practice for this to become automatic, says @thejulialion. Share on XRemember that the brain perceives stress subconsciously. If the body suddenly slams on the gas pedal, it is worth consciously reappraising the situation; in this case, building a purposeful awareness of the situation so athletes ask themselves:

- What emotion am I feeling and where?

- What am I stressed about?

- Is something dangerous?

- Is it actually negative?

Often, simply helping athletes become conscious of the situation—the stimulus/threat and the psychophysiological response—is enough to relieve their pressure instead of them helplessly drowning in it.

Sometimes, though, reappraisal is not sufficient in reducing the stress response. In the midst of high-pressure situations, athletes may default to over-controlling their movements, doubting their ability to compete, and using derogatory self-talk. It goes without saying that this makes the situation worse!

Through practicing and maintaining positive self-talk, athletes can bolster themselves against external pressure and noise. Encouraging an athlete to repeat positive affirmations of themselves or the training process (i.e., “I’ve trained for this. I am ready”)—or, as a coach, repeating it for and to them—is a straightforward, memorable way to reinforce this positivity. In this case, fake it until you make it does apply.

In situations when stress is not acute, but rather reoccurring or long-term, regeneration plays a vital role in the Maintenance Phase. Some stress, like long in-seasons, tournaments, or multiple back-to-back events, last more than a few minutes, hours, or days. It’s important that, just as in workouts, the rest periods and type of regeneration are adequate for and proportionate to the amount of stress being dealt with. Insufficient recovery can lead to fatigue and illness and, in worst-case scenarios, injury or burnout, all of which are suboptimal for high performers.

An athlete’s ecosystem can also be a valuable coping mechanism. Coaches should encourage athletes to seek out other things to focus on besides their sport, especially when it is a primary source of stress. Taking part in non-competitive hobbies, exploring new things, and having go-to people or places can help remove the constant concentration on sport, develop athletes’ self-awareness and self-concept, and remind them of who they are, regardless of competitive outcomes—they are complete human beings before they are athletes.

Damage Control

In absolute best-case scenarios, stress has been prevented and managed before ever arriving at this point. But sometimes stress, and the resulting performance decrements caused by it, just sneaks up from behind when no one is looking. To minimize the damage and return to mental fitness as quickly as possible, the athlete requires another set of coping mechanisms.

Developing and implementing mistake rituals can assist athletes in releasing distractions and regaining focus when errors have been made. If an athlete is prone to succumbing to their own negative self-talk (and even resignation), encourage them to instead mentally bookmark that mistake to return to later at an appropriate time for self-feedback.

Developing and implementing mistake rituals can assist athletes in releasing distractions and regaining focus when errors have been made, says @thejulialion. Share on XInstead of dwelling on their mistakes and losing focus in competition, instruct athletes to select a physical cue (shaking out hands, wiping off shorts, running hand through hair, etc.) or a verbal cue (“cancel,” “delete,” “forget,” etc.) to snap out of the cycle of “I’ve made this horrible mistake and now…” They should fight the urge to immediately overcompensate for the mistake, which leads to distraction and fatigue, using the mistake as motivation to continue performing well but not to stay in the past. Once an error occurs, it becomes a piece of the past and nothing they can do will change it. Thus, it is important to help athletes develop routines to mentally refocus on the present and tune into performing to their maximum capacity—no more and no less.

Athletes do not and should not have to handle stress crisis situations, whether seemingly big or small, alone. Athletes should be encouraged to reach out for help and use their surrounding resources, whether an on-staff sport psychologist, a social support network, their immediate team ecosystem (teammates, coaches, etc.), or others. It is also important that athletes are never shamed or alienated from their teams during times of stress—this makes “reentry” to the team, once the situation is solved, much more difficult, whereas peer and leadership support can help expedite the process.

Even in the Damage Control phase, recovery is still important. It is vital to focus on regenerating after large doses of stress. As coaches should know, contrary to the popular motivational phrase in the gym, rest is not earned. It is required for the brain and body to heal from the literal damage caused by stress.

This Too Shall Pass

As the player and I boarded the bus on our way back from the game, the young striker trying to shake off his disappointment from the missed penalty kick, I squeezed his shoulder encouragingly. “You did your best. We’ll work on it this week, so you have some strategies to help you in PKs next time. Enjoy your dinner.”

When we began the following training week, this athlete and I started to implement this three-phase strategy. We included more stress-protective elements in his mental training and practiced skills like positive self-talk and purposeful awareness until he felt confident that, should he feel so isolated in a high-pressure situation again, he would have the appropriate resources to meet the demands.

This mental skills training helped to reduce his stress, as he later reported to me that “even if I do get stressed, I know what it feels like, so it’s not scary and I have stuff to help me handle it now.”

He has not missed a penalty kick in the year since.

Regardless of motivation, determination, or level of mental toughness, everyone faces a stress crisis at some point, whether big or small, in the public eye or in private.

Giving athletes more useful skills and resources to meet the mental and emotional demands of sport can reduce negative feelings that result from pressure situations, says @thejulialion. Share on XAthletes are no different, especially in the very volatile, commoditized world of high performance. Giving athletes more useful skills and resources to meet the mental and emotional demands of sport can reduce negative feelings that result from pressure situations. Coaches should teach players to maximize resources, prepare, reappraise, and practice productive coping skills, and remind them that all stress does wane and pass at some point.

And they will recover.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Gordan, R., Gwathmey, J. K., and Xie, L. H. “Autonomic and endocrine control of cardiovascular function.” World Journal of Cardiology. 2015;7(4):204–214.

Haney, C. J. “Stress-management interventions for female athletes: Relaxation and cognitive restructuring.” International Journal of Sport Psychology. 2004; 35(2):109–118.

Lazarus, R. S. and Folkman, Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. 1984. New York: Springer Pub. Co.

Mellalieu, S. D., Neil, R., Hanton, S., and Fletcher, D. “Competition stress in sport performers: Stressors experienced in the competition environment.” Journal of Sports Sciences. 2009;27(7):729–744.

McCorry L. K. “Physiology of the autonomic nervous system.” American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 2007;71(4):78.

Miller, J.G. “The development of experimental stress-sensitive tests for predicting performance in military tasks.” PRB Technical Report 1079. 1953. Washington, DC: Psychological Research Associates.

Selye, H. “The stress concept today.” In I. L. Kutash & L. B. Schlesinger et al. (Eds.), Handbook on Stress and Anxiety (pp. 127–129). 1980. San Francisco: Josey-Bass.