[mashshare]

Throughout my professional career, I have traveled across the country visiting, as well as consulting, with many professional and collegiate athletic teams and programs. During these occasions, I have witnessed and been asked to evaluate various off-season and in-season athletic team training sessions and planned program designs. These observations, as well as my numerous discussions with physicians, rehabilitation professionals, sport coaches, and strength and conditioning professionals, expose a concern over the incorporation of high-level stressors (i.e., high-intensity exercise) into the athlete’s training program design. This apprehension (fear) appears to intensify at the time of the in-season training period, because, in addition to training, athletes also participate in team practice and game day competition.

To initiate this dialogue’s “elephant in the room,” I need to address the anxiety triggered by the distressful “what if” that arises during the course of an athlete’s training. In my four decades of professional practice in the related fields of sports rehabilitation and athlete strength and conditioning, as well as my time as the CEO of a 2,000+ employee, 185-facility physical therapy enterprise, my experiences have taught me to learn from the mistakes of the past, place emphasis on and address the concerns of the present, and make concise and well-thought-out decisions based upon factual information. Since initiating these principles, I’ve realized the large majority of “what if” fears will never come to fruition.

If an individual places focus upon the “what if” scenario of a possible fatal accident while driving a car, “what if” a deadly virus is acquired while wandering into crowded public settings, and “what if” serious injury transpires from participating in athletic competition, this individual likely wouldn’t drive a car, wouldn’t leave their home, and certainly would not participate in athletic endeavors. However, we can assume the majority of the population does not address life’s circumstances with this perspective. So why is there such a strong concern placed upon the “what if’s” during the athlete’s training?

Now, with that stated, the application of high-level stressors during training is not a free pass for the S&C professional to institute poor programming and inadequate training agendas or provide “off the cuff” imprudent decisions that are not well-organized, evidenced-based, or well-coached.

What Is a ‘High Stress’ Application?

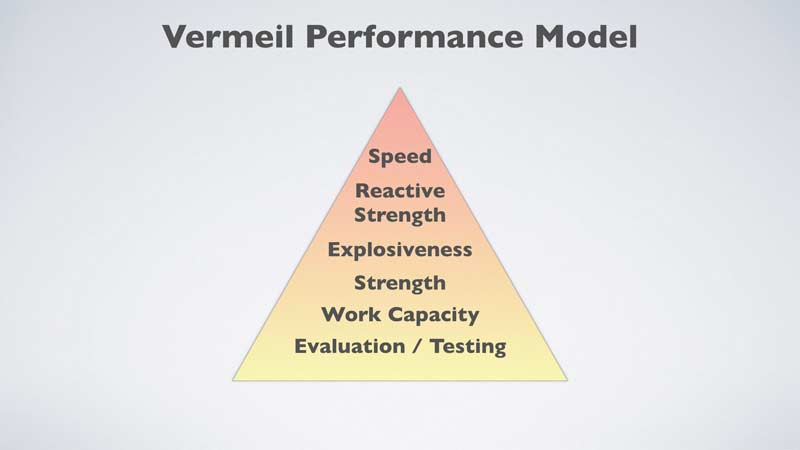

In my previous SimpliFaster blog post, I highlighted Al Vermeil’s Hierarchy of Athletic Development, as well as Hans Selye’s General Adaptation Syndrome, including the need for an unaccustomed stress application in order for physical adaptation to take place. High stressors are applied in the form of exercise “intensity” and may include, but are not limited to, exercise weight, exercise velocity, jump heights or distance, running velocity and distance, and many other activities utilized to enhance an athlete’s physical abilities. High levels of applied stress do not necessarily translate to the application of a heavy weight or high-velocity movements. High levels of stress refer to the application of a stressor to which the athlete is unaccustomed, resulting in a physical adaptation to that particular stressor.

An appropriate programmed unfamiliar stressor at suitable periods of the training cycle is needed for physical adaptation to take place. Share on XYou should also note that normally perceived “lower intensity” stressors may in reality be of “higher intensity” when utilized in the rehabilitation and training environments. Such a scenario may include a rehabilitation exercise progression to a 1-pound weight during a straight leg raise exercise where the patient previously had the limited ability to only lift the weight of their leg. “Healthy” high school and college freshmen who have no formal history of organized training would likely begin with lower stressor intensities (perceived as high to them) when compared to their seasoned peers. These same principles apply when introducing a progression of appropriate and significant high intensities (i.e., heavy weight, high sprinting velocities, etc.) founded upon the demonstrated abilities displayed by the experienced athlete during training. Regardless of the type of perceived intensity application, the premise remains that an appropriately programmed unfamiliar stressor at suitable periods of the training cycle is needed for physical adaptation to take place.

A review of Al Vermeil’s Hierarchy of Athletic Development (figure 1) demonstrates that strength is the physical quality foundation from which all other physical qualities evolve.

The physical quality of strength has been recognized to assist in injury reduction1, as weaker athletes sustain more muscle and mechanical damage when compared to their stronger peers2. Stronger athletes also display faster sprint times3, as well as the ability to change direction more rapidly and more efficiently4. When compared to stronger athletes, weaker athletes tend to rely more on ligaments for joint stability in high-intensity situations. This phenomenon is known as ligament dominance5, placing this group of athletes at increased risk of injury. During athletic competition, with athleticism and skill being very similar, it is the stronger athlete that will usually prevail. Strength is an essential physical quality in both the rehabilitation and athletic performance environments.

The Physical Quality of Strength

The physical quality of strength, as with any physical quality, is continually enhanced with the appropriate cyclic application of unaccustomed high intensity. You should evaluate and treat every athlete as an individual, as some may not be suited or properly prepared for the same high-intensity stressor applied to their peers. Proper preparation and the establishment of a work capacity are fundamental essentials often overlooked during the athlete’s training process. These fundamental essentials will help ensure future desired physical quality outcomes while allowing for suitable recovery and decreased threat of injury.

Proper preparation and the establishment of a work capacity are fundamental essentials often overlooked during the athlete’s training process. Share on XClearly, strength-based athletes such as powerlifters and Olympic-style weightlifters place no constraint upon weight intensity performance, as this is the outcome goal for success in these competitive sports. The objective for lifting weights in the team sport setting is to assist in the enhancement of the athlete’s physical qualities and athleticism, not for the creation of a competitive powerlifter or weightlifter. We should also note that other non-weightlifting activities such as sprinting and body weight exercises will also enhance strength qualities. However, we should not ignore that in many arenas of team sport competition, the athlete must produce high levels of force to overcome much more than their own body weight against the influence of gravity. Such examples include a football player breaking a tackle, hockey players fighting over the puck, basketball players rebounding under the boards, and wrestlers during match competition.

These examples substantiate the requirement for the application of external high stressor intensity during training. You should observe the following variables during the planning, as well as the execution, of a high-intensity exercise performance:

- Demonstrated body control and correct posture adjustments with associated proper technical proficiency as exercise intensity is progressively increased.

- Demonstrated applicable executed exercise velocity.

- Successful execution of the programmed exercise training intensities as related to the physical quality standards of the sport of participation.

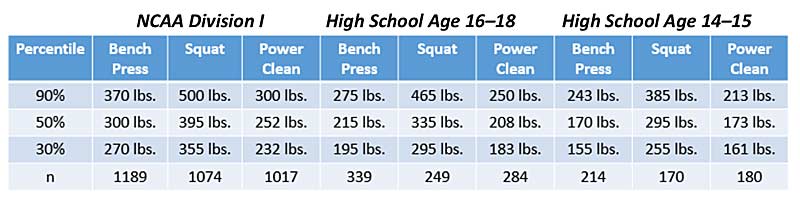

The physical quality standards of the sport of participation are utilized as a reference to establish a foundation for the preparation of the athlete to eventually compete in practice alongside their peers and on game day against their opponent. An example of the strength and explosive strength standards for the sport of American football can be found in figure 2

There is also an important relationship with regard to the programmed increase in high-intensity exercise and the athlete’s ability to control and maintain proper body posture(s) and technique during exercise execution. The acknowledgement of this relationship is essential to ensure for:

- Enhancement of the physical qualities necessary for optimal athletic performance.

- Sustained proper technical exercise proficiency resulting in the athlete’s optimal application of force against the external resistance.

- The velocity (i.e., rate of force development, impulse) at which the athlete’s executed force is applied.

- Physiological and biomechanical efficiency, for the proper distribution of the applied stressor upon the athlete.

- Safety from injury.

Another consideration often asked about is how high a level of applied stress is enough. In addition to the physical quality standards of the sport of participation, a balance should exist between these sport standards and guideline limitations placed upon high-intensity applications. Using the squat exercise as an example, the general rule for the athletes trained under our supervision is a full squat exercise weight intensity limitation of twice their body weight. Once accomplished, the emphasis is placed upon exercise execution at higher velocities at this same high (as well as all) exercise intensity.

This philosophy of training transpired during an “ah-ha” moment while working with my good friend, Hall of Fame S&C Coach Johnny Parker, during many off-seasons with his NFL New York Giants players. During the 1980s, Coach Parker and I also met and worked with a former Soviet weightlifter and weightlifting coach named Grigori Goldstein. On one particular occasion, we witnessed a NY Giants player who had executed a successful 425-pound squat at a body weight of 178 pounds. When Coach Goldstein was asked how to continue to make this particular player stronger, he responded: “You don’t need to make him stronger. You need to have him move the bar faster.” Progressing this player through what would eventually become Vermeil’s Hierarchy of Athletic Development would be much more beneficial for his overall athletic performance than continuing to focus on making him stronger.

There are exceptions to every rule, and the two-time body weight squat limit is no exception. There was an outstanding running back with the Giants for many seasons (he was also a member of the 1986 Super Bowl Championship team). At a stature of 5 feet 7 inches and a body weight of 202 pounds, this player also performed a 620-pound full squat. If his squat exercise limitations had been set to two times body weight—i.e., 404 pounds—he likely would not have physically endured a single NFL season or had his outstanding NFL career.

All athletes should be evaluated for high-intensity limitations and exceptions based on such criteria as their stature, the standards of the sport, and their position of participation. Share on XIn hindsight, when considering the “risk vs. reward” with regard to a high-stress application, Coach Parker and I often discuss whether this player would have been as successful if his squat exercise intensity had been limited to 500 pounds or 550 pounds with increased barbell velocities versus three times his body weight. All athletes should be evaluated for high-intensity limitations and exceptions based on such criteria as the athlete’s stature, the standards of the sport, and the position of participation. For example, does an Olympic fencer need to lift as much weight as a football lineman?

Lifting Heavy Weights In-Season

During the aforementioned discussions, there is increased apprehension over the inclusion of high-intensity exercise performance during in-season training. This concern appears to be centered upon the inclusion of team practice, as well as game day competition. However, we may then ask, if an athlete executes high-intensity exercises during their off-season training, where they may also achieve personal records (PR’s), why then during the most important time of the year is there a hesitation to prescribe high-intensity training?

If you establish in-season training intensity limitations at, let’s say, 80% of the athlete’s previous off-season physical performance, why then have the athletes perform so diligently during the off-season? Where is the logic to attaining substantial off-season physical achievements and not at least maintaining, if not continuing to improve, these achievements during the competitive season? Would any sport coach instruct any athlete to limit their physical abilities to an 80% effort during game day performance? Is a 20% reduction in effort considered acceptable? If a reduction in effort is not deemed acceptable, why then is any programmed deficit during the in-season training considered not acceptable as well? Not only will a weaker athlete likely perform at less than optimal, but a continual loss of strength due to the physicality of a long season in conjunction with a steady application of a shortfall (inadequate) intensity may also set the stage for possible injury.

The philosophy for in-season high-intensity stress application was introduced to me in the fall of 1996. Coach Parker was now with the NFL New England Patriots, and numerous discussions led to high-intensity weight applications of 90% or greater at appropriate training periods during this particular in-season. At the conclusion of the 1996 NFL competitive season, 35 New England players set PR’s in one or more of the foundation exercises (i.e., squats, cleans, bench press, etc.) as the team entered the NFL playoffs. Wouldn’t we, as coaches, aspire for our athletes to physically “peak” at the most important time of the year, the time of the post-season playoffs? This same Patriots team eventually competed in that same post-season Super Bowl XXXI.

The Relationship Between Exercise Volume and Intensity

Higher programmed exercise volumes have an inverse relationship to exercise intensity. As an example, if an athlete performs a squat exercise with 100 pounds for 10 repetitions and their exercise descent and ascent are both 2 feet in distance (a total distance traveled of 4 feet), we would calculate the total work performed (work = force x distance) as 100 pounds x 4 feet x 10 repetitions = 4,000 ft. lbs. If the same athlete squatted 150 pounds for five repetitions, the work performed would now be 150 pounds x 4 feet x 5 reps = 3,000 ft. lbs., resulting in a 25% less overall quantity of work performed (i.e., 3,000 vs. 4,000 ft. lbs.). However, the same athlete would also execute a 50% higher quality of work (i.e., 150 lbs. vs. 100 lbs. per repetition). Appropriately programmed in-season high-intensity exercise execution corresponds with a lower volume of work. Reduced exercise volumes also help avoid the excessive physical fatigue that may lead to many physical consequences.

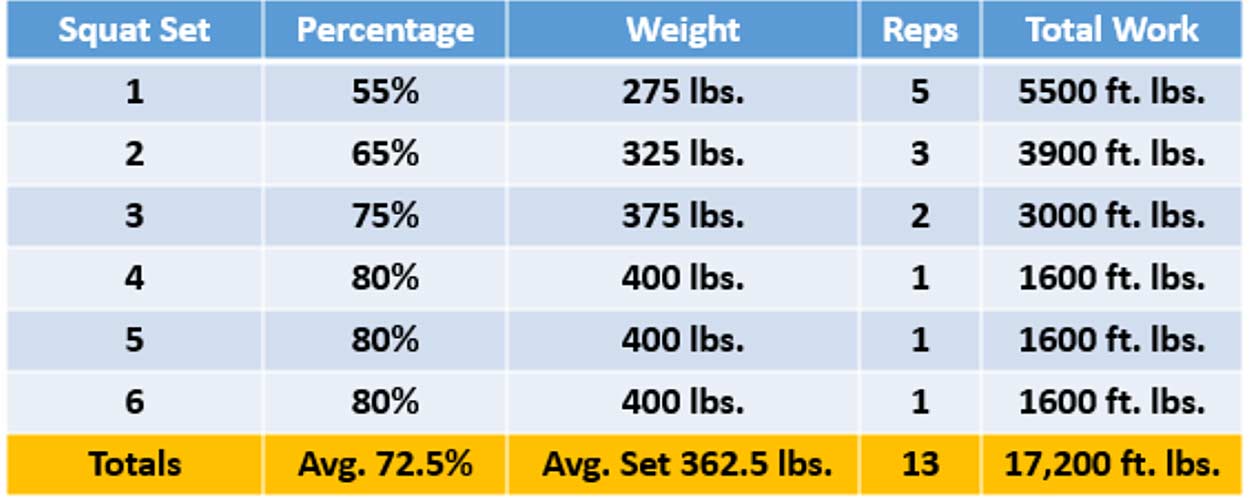

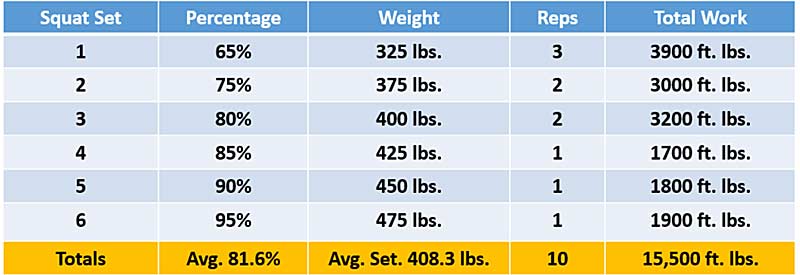

Appropriately programmed in-season high-intensity exercise execution corresponds with a LOWER volume of work. Share on XUsing the above example, I present two in-season squat workouts (after warm-up) below. Figure 3a represents an actual college football in-season squat workout limited to 80% exercise intensity. Figure 3b represents a higher exercise intensity in-season squat workout. Both programs are based upon an athlete’s demonstrated 500-pound squat performance.

Figure 3a demonstrates that an increased amount of work (17,200 ft. lbs. vs. 15,500 ft. lbs.) may be achieved with the programming of lighter weights, thus enhancing the athlete’s ability to perform more exercise repetitions. However, the average squat set quality of work is approximately 21% lighter in the limited intensity workout when compared to figure 3b, the high-intensity workout (362.5 lbs. vs. 403.8 lbs. respectively). A lesson imparted upon me by both legendary track coach Charlie Francis and my good friend Derek Hansen is a concept that is easy for many coaches and rehabilitation professionals to understand, but difficult for them to trust. Physical performance at 90–95% of an athlete’s abilities is still submaximal; thus, these high intensities are still safe to perform. The attempt to execute excessive exercise volumes at these high intensities is what subjects the athlete to possible injury.

In addition, a greater amount of accumulative in-season exercise volume (work) may eventually lead to excessive physical fatigue, setting the stage for overtraining, poor recovery, decreased on-the-field performance, and eventual soft tissue type injury. An additional consequential risk that low-intensity, higher volume workouts may present is the illusion of a light workout session when the reality is often the opposite. As demonstrated in figure 3a, lower intensity “light” work sessions may transform to “heavy” work sessions due to the greater-than-anticipated quantity of work performed. It is acknowledged that during the course of training, athletes require days off and “unloading” workouts to assist in recovery and avoid overtraining. However, athletes remain “fresh” by maintaining (as well as enhancing) their strength levels during the competitive season, not by persistently resting.

Do Athletes Sprint Enough in Season?

There also appears to be a reluctance to incorporate appropriate levels of high-velocity (intensity) sprinting during the competitive season. Once again, this hesitation appears to be due to the concern for injury, and more specifically, the onset of soft tissue injury (i.e., hamstring strains). Sprinting is required not only for enhanced athletic performance, but the prevention of high-velocity injury as well.

Sprinting is required not only for enhanced athletic performance, but the prevention of high-velocity injury as well. Share on XIf an athlete isn’t acclimated to the repetitive high-velocity movements that occur during practice, competition, and the prolonged competitive season, how then could there be expectations for them to remain healthy under such stressful physical circumstances? The following are benefits to incorporating high-intensity (velocity) sprinting during the athlete’s in-season training.

- Enhances running velocity – Stating the obvious, to maintain and possibly enhance an athlete’s running velocity, the athlete needs to run at high velocity. Sprinting is the purest plyometric activity and will enhance the physical qualities of strength, explosive strength, and elastic strength. Although some athletes may rarely achieve 100% of their maximal velocity during their sport of participation, the enhanced starting abilities (i.e., first step) and improved acceleration capabilities associated with high-velocity sprinting will also help contribute to optimal athletic performance.

- Enhances the speed reserve – Higher running velocities will also enhance submaximal running velocities (i.e., 80% of an improved running velocity is faster than 80% of the previous lower running velocity). The athlete will also improve their physiological and energy efficiency (economy) at these new high and submaximal running velocities, as well as consistently maintain these velocities throughout the game day competition.

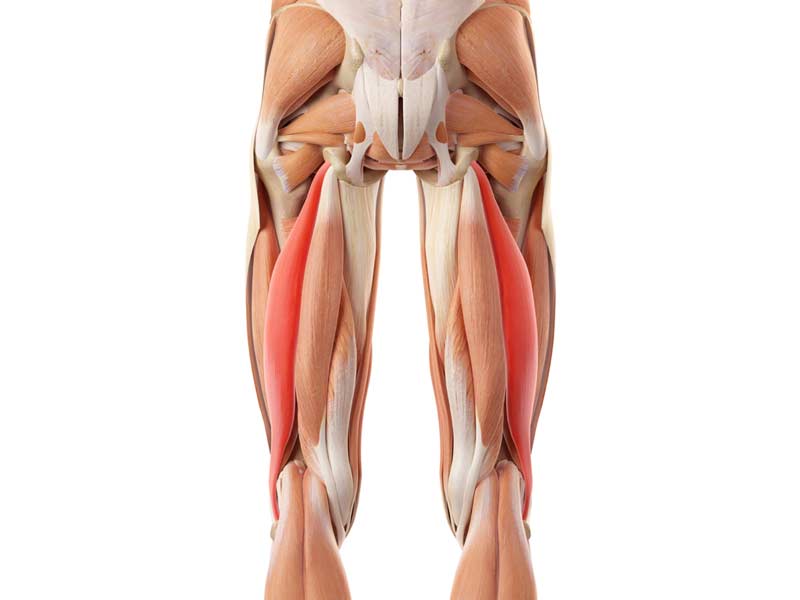

- Improves neuromuscular efficiency and timing – Sprinting will provide a stimulus to both enhance and “fine-tune” rate coding, contractile velocities, and efficiency of recruitment. Maximal muscle activation of the medial (semitendinosus) and lateral (biceps femoris) hamstring muscles occurs at different musculotendon lengths7 and at different time intervals during the running cycle. Precise timing for these differences in activation to happen is crucial for both performance and injury prevention.

- In addition, the lateral hamstring muscle, the biceps femoris, consists of two heads, a long head and a short head (figure 4). These two distinct anatomical components of the muscle also have two different and distinct nerve innervations, the tibial nerve (long head) and the common peroneal nerve (short head). For the athlete to maintain and/or achieve the proper neuromuscular efficiency of the medial and lateral hamstring muscles, as well as the proper timing of the nerve innervations to the long and short heads of the biceps femoris muscle at high velocity, the athlete must perform at high velocity.

- Improves the coactivation index of the lower extremity musculature – The coactivation index is an additional neuromuscular consideration for training at high velocities. During slow-velocity movements, including those with applied high intensity, agonist and antagonist muscle groups work amicably together over the prolonged exercise period to stabilize the joint(s), demonstrating a coactivation index (ratio) of approximately 1:1. High-velocity movements are dependent upon brief periods of time requiring a prominent contribution from the agonists, while the opposing antagonists must demonstrate a lower level of activity.

The “quieter” the antagonists, the less opposing they will be, resulting in a higher contribution of the agonists for ideal force application. This emphasized contribution by the agonist muscle groups corresponds to a shift in the coactivation ratio, favoring the agonists muscle groups. The highest skilled athletes are those with the ability to completely relax their antagonist muscle groups during high-velocity activities, as rigid and “rough” movements are likely the result of poor coordination between agonists and antagonists.

One of the Last Advantages

The programming of high-intensity training via the application of unaccustomed stresses is necessary for physical adaptation to transpire. The application of high stressors during off-season training will continue to improve the physical qualities necessary for optimal athletic performance. In-season high-intensity training will maintain, if not continue to improve, the physical qualities attained during the off-season training. The appropriate incorporation of high-velocity in-season sprinting will also maintain and possibly improve the athlete’s running velocity.

Appropriate in-season sprinting will also assist in the prevention of soft tissue injury, due to maintaining or enhancing the athlete’s strength levels, intermuscular coordination, and neuromuscular timing. As many athletic teams have off-season training requirements as well as training facilities available to them, the application of high-intensity stressors during in-season training may be one of the few advantages remaining in competitive team sports.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

1. Lauersen, J.B., Andersen, T.E., and Andersen, L.B. “Strength training as superior, dose-dependent and safe prevention of acute and overuse sports injuries: a systematic review, qualitative analysis and meta-analysis.” British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2018; 52: 1557—1563.

2. Newton, M., Morgan, G.T., Sacco, P., et al. “Comparison between trained and untrained for responses to a bout of strenuous eccentric exercise of the elbow flexors.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2008; 22(2): 597–607

3. McBride, J.M., Blow, D., Kirby, T.J., et al. “Relationship Between Maximal Squat Strength and Five, Ten, and Forty Yard Sprint Times.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2009; 23(6): 1633–1636.

4. Watts, D. “A Brief Review on the Role of Maximal Strength in Change of Direction Speed.” The Journal of Australian Strength and Conditioning. 2015; 23: 100–108.

5. Hewett, T., Ford, F., Hoogenboom, B., et al. “Understanding and preventing ACL injuries, Current biomechanical and epidemiologic considerations – Update.” North American Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 2010; 5(4): 234–251.

6. Hoffman J. Norms for Fitness, Performance, and Health, Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL, 2006.

7. Higashihara, A., Nagano, Y., Takashi, O., et al. “Relationship between the peak time of hamstring stretch and activation during sprinting.” European Journal of Sports Science. 2016; 16: 36–41.