The most common issues I find in the weight room with softball players seem to revolve around three limitations of movement1. The same movement limitations I see in the lifts we do also show up as restrictions to demonstrating accuracy, power, and speed on the field.

Because swinging, throwing, and pitching are very technical aspects of softball—due to the need for accuracy with each rep—patterning in quality movement reps in the weight room is even more crucial for athletes involved in these elements of the game. When an athlete completes reps of a movement 10-20x per session, 2-3x a week, the faults of their lifting patterns will also show up in the sport. These faults can affect accuracy, limit power, and promote the risk of injury.

When an athlete completes reps of a movement 10-20x per session, 2-3x a week, the faults of their lifting patterns will also show up in the sport, says @shestrength. Share on XAs coaches, trainers, and parents, paying attention to even the smallest details in our girls’ lifts can have the biggest impact on their performance in the sport of softball.

Problem #1: Curve or “C” in the Back with Heavy Lifting1

I most commonly see this error in the weight room, with squatting, deadlifting, and overhead pushing/pulling movements. This subtle issue places the load of the weight onto the spine and off of the muscles of the glutes/core and legs.

On the field, I most often see this movement error in swinging a bat and/or pitching. This error prevents the athlete from accessing the oblique sling and the core as a connector between the lower body and upper body, leading to a loss of power and the athlete only using the upper body as a driving force to rotate.

Video 1. An example of power loss at contact through the core using the Core360 belt. In this video, the athlete loses her core stiffness at the desired contact point by bending her torso to the side leading with her head tilt. This loss is noted by the drop in the blue lines measured by the sensor at the same desired point of contact. Power loss is a common issue when an athlete cannot rotate correctly.

Video 2. An example of power increase at contact through the core using the Core360 belt. In this video, the athlete maintains core stiffness and does not swing with a “C” bend in her back. This is noted by the increase in core pressure at the desired point of contact in her swing.

Solution: Flatten out the low back by creating core stiffness.

In the weight room, I place athletes in positions for lifting that force the C out of their low back as much as possible, hoping that it eventually creates the correct patterns in sport. These are lifts such as landmine squats and landmine pressing, side planks, elevated boxes to deadlift from, and foot support (using a bench or box) for overhead pulling movements such as chin-ups. We also implement specific warm-up drills to help create core stiffness and pelvis control. These include slow and controlled exercises like deadbugs, bird dogs, side planks on knees and elbows, crawling patterns, rolling, and anti-rotation ISO holds using bands and a partner.

Video 3. A demonstration of the crawling core stiffness drill in warm-ups. The shoe helps the athlete have a tactile cue to keep her hips from swaying and her spine extending/ compressing as she crawls.

Video 4. A demonstration of a core stiffness drill with bird dogs and bands. This drill is a step up in difficulty from the drill in video 3; now, the athlete must maintain core stiffness in an offset loaded variant of the bird dog using a band and lateral resistance.

Problem #2: Stabilize Through the Neck

I commonly see an athlete tighten her shoulders, traps, jaw, and neck when doing rotation and anti-rotation exercises, ab exercises, and most pulling exercises. This removes the core as the stabilizing mechanism and places the power source in the neck, jaw, and shoulders. These are not designed to bear the load of that much power and weight. This issue also reduces the ability of the legs and core to get stronger.

On the field, we most often see this in pitchers who push off the mound headfirst. It also shows up in sprinting between bases and swinging a bat (pulling the head off the ball). This common error causes the same troubles for the body in sport as it does in the weight room—it forces the joints to take the brunt of the work instead of the muscles. This leads to a loss of power and speed because the legs are not the main drivers. And in hitting, this issue pulls the eyes off the ball, making it hard to connect with a pitch.

Using the neck as a stabilizer causes the same troubles for the body in sport as it does in the weight room—it forces the joints to take the brunt of the work instead of the muscles. Share on XSolution: Use the feet and legs.

Most girls struggle with using their legs for strength and instead want to overpower a lift with their upper body. Cueing an athlete to find her feet, or push the floor away with her feet, or drive her legs/feet into the floor in almost any lift can help.

She has it figured out when she feels her legs begin to shake and her core fire up, releasing the neck from stabilizing the load being lifted. The idea is that feeling this in the weight room will allow an athlete to find her front leg both in a pitch and swinging a bat. This will provide a stable stance base for the body to rotate through. It also allows the ground force production from the foot to travel up through the core and out the hands.

Video 5. A demonstration of removing the neck as a stabilizer in pulling exercises. I use different strategies to help an athlete “feel” how to use their core and feet as stabilizers, NOT their neck. I hold a PVC pipe along the athlete’s spine and ask her to keep her entire spine aligned with the “fake spine” (PVC pipe) as she pulls the band back and down.

Video 6. A demonstration of using J-cups to help the athlete find their foot load. I flip the J-cups over and place the barbell under them, get into a squat position, and press up and into the J-cups using my feet. This elicits the feeling of active foot loading and creates core pressure if the athlete is in correct alignment from their ribs to hips.

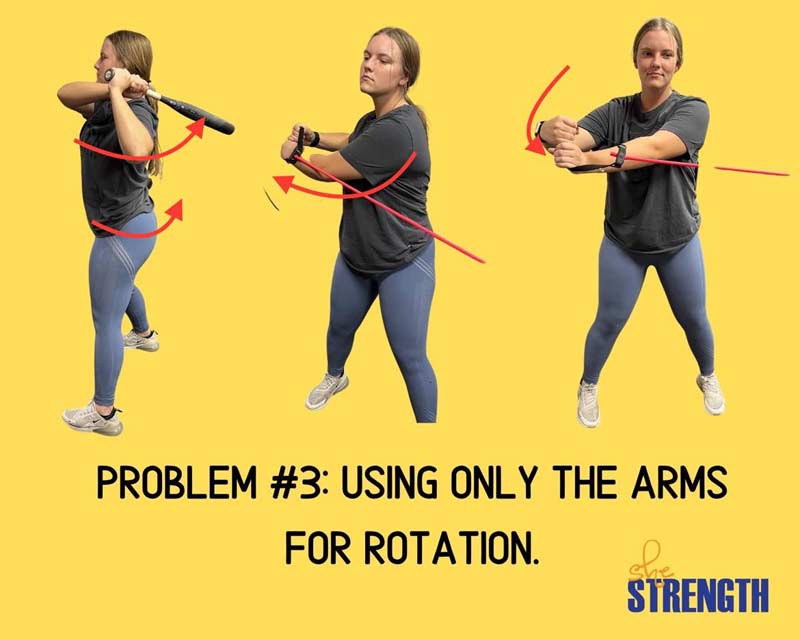

Problem #3: Using ONLY the Arms for Rotation

In the weight room, I often see an athlete try to avoid true rotation through the core by bending or extending/flexing through her shoulders, arms, and wrists as compensation. I see this happen with anti-rotation and rotational ab exercises, rotational pulling, and pushing movements.

The arms and wrists can only provide so much power disconnected from the core and the lower half of the body. When the athlete avoids rotation by bending her elbows and arms/wrists, the core is bypassed as a source of strength. The old saying “when the joint ends, power ends” applies here. An athlete will eventually reach a ceiling in their strength progressions in the weight room because the upper body can only sustain certain compensations for so long.

On the field, we most commonly see athletes swing, throw, or pitch using only their arms and upper body. As in the weight room, this absence of the core connecting the lower body to the upper body leads to a loss of power.

Solution: Use the oblique sling connecting the feet, hips, core, and arms through rotation.

Learning what access to the oblique sling “feels” like is critical for athletes to know how to access it for strength and power.

Learning what access to the oblique sling ‘feels’ like is critical for athletes to know how to access it for strength and power, says @shestrength. Share on XIn the videos below, I demonstrate several ways to incorporate “feeling” the oblique sling to create core connectedness using bands and dumbbells.

Video 7. A demonstration of an anti-rotation exercise using bands.

Video 8. A demonstration of oblique sling presses using dumbbells.

Video 9. A demonstration of oblique sling separation using medicine balls.

Results on the Field

After addressing these three issues with athletes and spending consistent time working to break down old movement patterns, athletes can feel and see added power in their swings. We retest using the Core360 belt every 6-8 weeks to assess where athletes are in the positioning of their swings and how it translates to core power. I also constantly quiz my athletes and their coaches on what they see and feel in practices and games.

In addition to more power, many athletes report less low back and shoulder pain with their lifting. The last determining factor of measurement I use is athletes reporting new soreness in the specific muscles we are targeting because we have removed overcompensations. Now we are focused on true muscle activation and growth.

Special thanks to Allie Stipsits, sheStrength intern and Hutchinson Community College softball athlete, for her contributions and serving as the model for the infographics.

Attribution

- I’ve learned many of these principles from chiropractors such as Dr. Jared Shoemaker (inmotionsmj.com), physical therapists, and other professionals mentored by doctors, neurologists, etc., in a new rehabilitation technique called Dynamic Neuromuscular Stability (DNS). These neurological techniques are based on clinical protocols to restore and stabilize locomotor function. From these techniques, I’ve found ways to creatively incorporate strength and motor function into workouts our softball players complete weekly to help rebuild better movement patterns for their sport.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF