Preparing teenage athletes for the upcoming high school football season is a yearly ritual for coaches across the country. The demands on the athletes are not just physically intense but mentally intense as well. For decades, the traditional thoughts on “conditioning” athletes for these demands included a wide variety of exercises, with selections such as multiple shuttle runs, sets of 100s, bear crawls, and other implements of fatigue used to condition athletes for the sport’s demands. They were also widely believed to build the toughness needed to play the game.

While most programs run training sessions throughout the summer, we all know that many athletes will miss at least part of those sessions. The question facing coaches is how should they account for the highly variable training gap of the athletes once mandatory practices and camps begin? While many athletes will begin camp fully prepared for those challenges following months of attendance at voluntary sessions, others may miss weeks with vacations, travel sports, jobs, or other obligations.

The coach’s ego in many of us would like to say, “well then, they don’t play,” but the reality is that for many programs, that’s not a realistic option. They need the athletes to be not only present once camp begins but also healthy and available. How can coaches be assured that the workload done and capacity built by each athlete meets the demands they will face? On the flip side, how can we be sure that we are not needlessly pushing our athletes past the point of meeting those demands? Are we potentially negatively affecting performance by adding unneeded fatigue to athletes who have already reached their needed load for optimal performance?

For our multidisciplinary performance team at York Comprehensive High School (sports coaches/performance and athletic training staff), wearable GPS for our athletes has been the answer to these questions. GPS has also allowed us to keep our athletes within the optimal ratios of velocity, load, and change-of-direction speeds that mirror those of the sport’s demands but are sometimes left short in sport preparation.

Volume is a great place to start when first dipping your toes into the use of GPS—you can use it to create data-driven, individualized programming to develop optimal work capacity. Share on XThis article is the first in a series of the how and why behind the use of TITAN GPS units. In this installment, I want to focus on using a basic metric that many without access to GPS already use to build work capacity: volume. Volume is a great place to start when first dipping your toes into the use of GPS—it can be used to create data-driven, individualized programming to develop optimal work capacity that meets the demands of a high school football season.

Implementing GPS Data

The answer for our program (and an ever-growing number of programs at the high school level) has been to implement GPS to track our athletes and then use the information we gather to make informed, data-driven decisions on how to train them to be optimally prepared for the demands of the season. GPS can eliminate most of the guesswork and guide coaches to informed decisions. Our primary goal as sports performance professionals is the health and wellness of our athletes, and GPS can not only be an effective tool to drive this goal in-season but also year-round. This ensures athletes are prepared for the challenges of the type of grueling off-season schedule common at the high school level.

One key point I’d like to make is that this article is solely aimed at the high school level. I firmly believe that the main mistake I made in laying out our off-season program before I had GPS to guide me was trying to design a scaled-down, college-level programming plan. What GPS showed me from day 1 was the extreme amount of sheer volume a high school athlete maintains year-round. College coaches may have a block of 4–8 weeks, then an extended non-contact period—those may be sprinkled throughout the year, and the NCAA governs the time they are allotted with the athlete.

At the high school level? That simply isn’t the case in most situations.

In his pregame speech before our week 1 kickoff, our head coach said: “You guys have spent 180 days in school, 90 minutes a day training. We had 16 spring practices, 20 summer workouts, and 20 summer practices. We played 30 passing league games and participated in four lineman challenges. We have practiced for three weeks and played three scrimmages. If we are not ready now, we never will be.” Amen, Coach. Take a second to re-read that…then explain how does continuing to add a few hundred yards of conditioning a week improve performance. If you do, you are probably guessing, whereas GPS allows you to answer those questions with a high level of confidence.

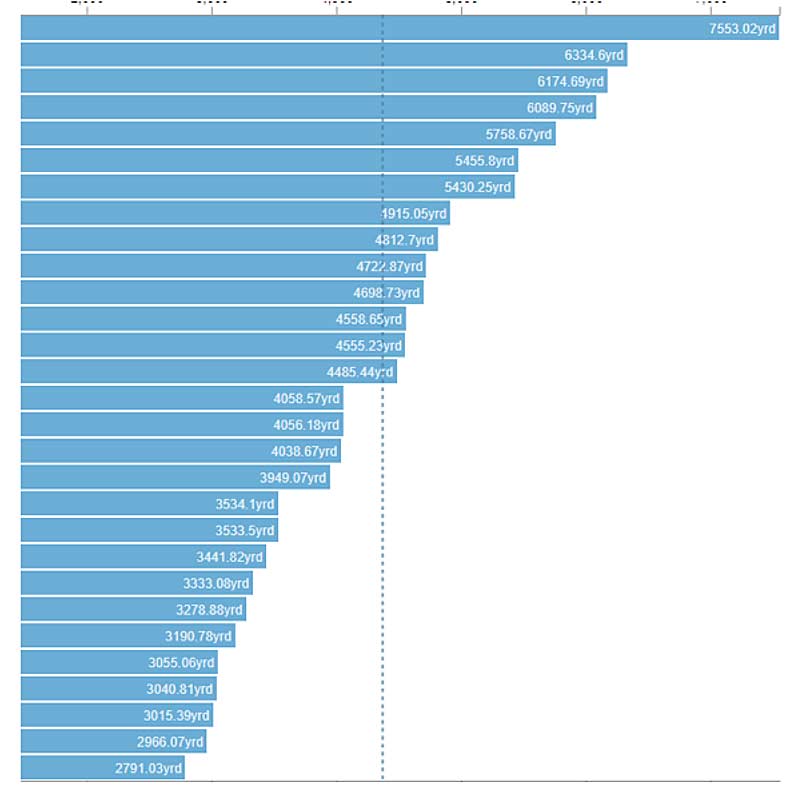

Another challenge faced by coaches who do not use GPS is prescribing a generic volume or rep scheme to athletes who have a wide variance in work done, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XAnother challenge faced by coaches who do not use GPS is prescribing a generic volume or rep scheme to athletes who have a wide variance in work done. Below is an average practice volume in yardage above 2 meters/second.

I can attest that this is just an average in-season practice from week 1 of our regular season. The range is quite varied, from the most at 7553.02 (a two-way starter at WR/FS) all the way down to the least at 2791.03 (backup QB). Eight of the bottom 10 athletes are offensive linemen or interior defensive tackles. The other two? Our starting QB (who ran for well over 1,000 yards last season) and a backup running back.

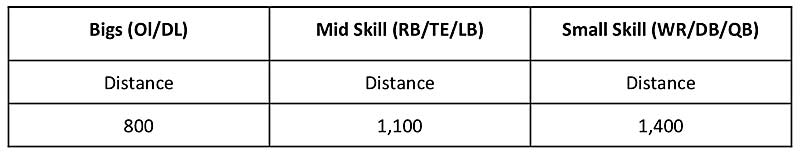

My preparation prior to GPS would have included ranged volume and distances based on position. This is a random example of a 2017 pre-season week:

The assumptions were close to correct. In general, the bigs need the least prep, and the WR/DB need the most. The QB position is way off: in fact, the in-game needs of our starter in 2021 were between 3,458 and 3,845 yards above 2.0 m/s. Another miss? Eight of the top nine totals were WR/DB guys. However, the fifth-highest total in practice (and it holds true in game capacity as well) was our starting running back.

My point? While my educated guess was accurate for many athletes, other guesses were off. Volume is not the most powerful tool to prepare athletes for demands—we will discuss “player load” in a later article (which is better, in my opinion, because it builds in intensity and time). BUT, if you choose to use volume as a way to progress your athletes toward the demands of the season, as I did, then GPS can be a way to ensure individual athletes are truly prepared for what they will face from a volume standpoint.

Assigning a generic volume prescription and not considering individual demands is a guess. It is also a guess based on a huge variable that’s totally missing. When we put those numbers on paper and lay out the linear wave periodization of volume (as many non-GPS users do), we are attacking it as if every athlete is beginning our session at the same point. But that is simply not true.

Looking at the practice above as an example, if we had run 400 yards of shuttles after practice, that would have taken our top-volume small-skill athlete to 7,900+ yards and our very lowest small-skill athlete to 3,191. The issues?

- What if our backup QB has to become our starter suddenly? That 3,191 may end up being too low to match his increased load in practice.

- For this particular athlete, 7,553 is above what we know he requires to meet the demands of game or practice. In fact, my suggestion for him would be to go home and recover, not add fatigue to a work capacity load that already exceeds need.

Another possible scenario involves athletes who have missed practices or workout sessions. Should they be dosed with the same prescription as the athlete with 21,000 yards during that same time?

Using volume to build work capacity has definite value. But we should not pretend that doing so without data to guide us and digging into each athlete’s acute and chronic loads is anything more than a best-educated guess.

In the three years we have been using GPS, we have all but eliminated any extra conditioning after practice. We have also seen little to no cramping in the early season. In addition, our non-contact soft tissue injuries have dropped significantly (according to internal reports). At the time of this writing, we are in the early part of our season, which began with spring ball in May. We have had zero missed practices due to non-contact soft tissue injuries.

In the three years we have been using GPS, we have all but eliminated any extra conditioning after practice. We have also seen little to no cramping in the early season, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XWhile this data is purely anecdotal, I firmly believe in our multidisciplinary approach and its positive effect on athlete health and wellness. With the data to guide us, anything and everything we do has a definitive reason. We can adjust practices to increase or decrease volume and intensity to match the actual needs of the athletes.

Instead of doing things because we always have or because it makes the coaches comfortable, we can dial in and work toward an optimal high-performance training plan. We can focus on intentional acceleration or max velocity development and not be concerned with whether we are conditioning or not. When we do see a need for increased work capacity, we have the ability to know which athletes are in need and target those needs.

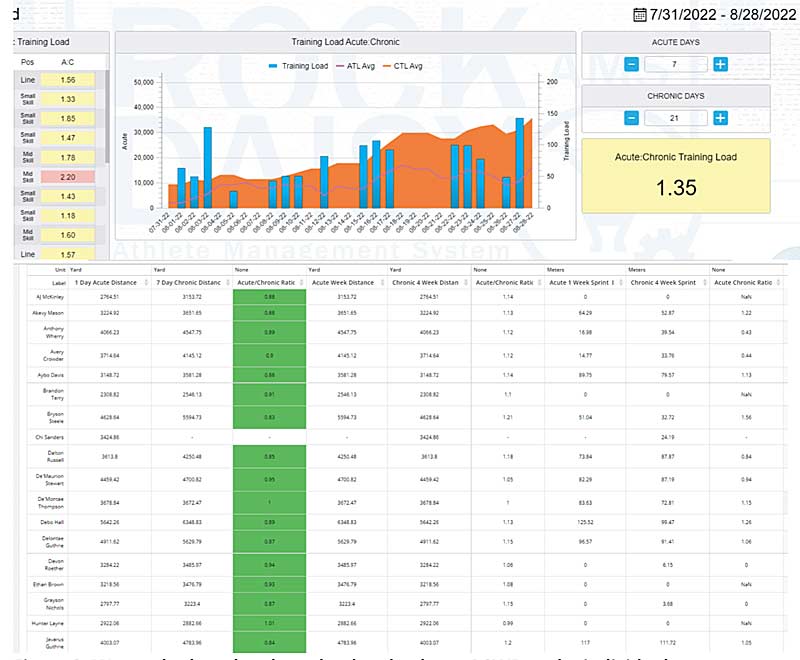

Using volume to guide programming is just one way to progress your athletes. It is the most basic use of the data that can be collected. In the next installment of this series, I will dive into using player load (PL) and acute:chronic work ratio (ACWR). Using these metrics has allowed us to become even more precise in preparing our athletes for the demands of not just playing but preparing for sport.

Using PL brings intensity and time into the picture. ACWR gives you a way to look at the bigger picture using PL. I will also cover how we use high-speed (90%+ of max velocity) sprint data and high-speed acceleration and deceleration as guides to fill the buckets that practice may not always succeed in doing. GPS guides the way to make these decisions without guesswork.

I believe each athlete should be prepared to meet the specific demands of their sport. My mistake before GPS was feeling that if I didn’t build the capacity for work needed by our athletes, then it wasn’t taking place. Having the data available has shown me that simply is not the case. In fact, much of the time, what I was adding to the athlete was above and beyond their need.

My mistake before GPS was feeling that if I didn’t build the work capacity needed by our athletes, it wasn’t taking place. Having the data has shown me that isn’t the case, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XDo I believe it was detrimental to the athletes? Maybe, maybe not. However, our top priority needs to be “do no harm.” Unnecessary activity done well above and beyond need not only takes time away from the attributes that could positively affect performance but also delays the recovery process that most high school athletes struggle with organically. Instead, the focus can be on providing the things the athlete does not get from off-season preparation within their sport. GPS helps increase our value to the sports coaching staff and our ability to run an athlete-centered program.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF