Matt Kane is the Women’s Associate Head Coach at Florida State University, where he specializes in hurdles and women’s sprints. In 20+ years of coaching, he has worked at many levels, from Junior College to NCAA, as well as World Athletics and Olympic Games. Kane has coached multiple athletes to World Championship Medals and NCAA Championships, including this year’s NCAA Champion and World Silver Medalist Trey Cunningham.

Freelap USA: You were one of several successful coaches who went through Barton Community College. What about that environment do you think helps foster further success in a coach’s career?

Matt Kane: There have been several prominent coaches who spent time early in their career at Barton, such as Dennis Shaver and Lance Brauman, among others. I think one of the reasons Barton has been a place from which coaches have gone on to do great things is the constraints placed upon the coaches while there. Back then, the facilities were still developing, and the weather in that part of the country can vary a lot; this required us, as coaches, to be flexible and have contingency plans in place.

Adaptability and the ability to adjust on the fly are important qualities as a coach, and Barton provides this experience. So, when a coach moves on elsewhere, and there are fewer constraints, the job is made easier—should adjustments be required for whatever reason, it’s no big deal.

I also believe that, for most people, Barton was somewhat a part of a career progression, and therefore, this meant that the coaches and the athletes were always working to move on to the next level. This created a highly competitive culture, which fostered a lot of success. For example, there were something like 24 Olympians from Barton over a four Olympic cycle period. As this success grew, winning became the expectation, which meant that the quality of coaching had to be constantly raised to continue to meet that expectation.

Freelap USA: As an athlete, it is often challenging to complete a collegiate season and then immediately compete on the professional circuit. However, Trey Cunningham seems to have done an excellent job of that this year. What strategies did you have in place to make this transition run as smoothly as it did?

Matt Kane: For Trey in 2022, the professional season was always a part of the plan. Of course, we wanted to win the NCAA 110-meter hurdles, but we also wanted to make the U.S. team for the World Championships and win a medal in Eugene. This meant there were some adjustments made for him as compared to an athlete who would finish their season at the NCAAs. For example, Trey raced less frequently, typically once every two weeks.

One of the things I was most happy with was that three weeks after the World Championships, without any races in the interim, Trey had his first-ever race in Europe. He ran 13.03 in Monaco, despite having only arrived there 48 hours earlier. I think the main factor here was that I kept the training fairly similar and didn’t make any drastic changes.

For instance, the weight room continued until the middle of August. I think that when the training load gets reduced too drastically and too soon, there’s a risk that the athlete’s performance level will decrease significantly. So, as long as Trey continued to tell me he felt good, we just continued as normal.

Freelap USA: When I asked you about your training philosophy, one of the points you made was, “allow them to be them.” Can you elaborate a little on what you mean by that and maybe give an example?

Matt Kane: This aspect is a big part of my philosophy on coaching and doesn’t necessarily just refer to what happens in workouts or athletically, but also how they are as a person. If I can provide an environment where an athlete is comfortable in their own skin, then I think it helps them to be more confident, and that is helpful in allowing them to bring the best out of themselves.

‘Allowing them to be them’ is a big part of my philosophy on coaching and doesn’t just refer to what happens in workouts or athletically, but also how they are as a person, says @killakane_fsu. Share on XMore specifically related to workouts, I ensure I don’t force an athlete to be like someone else. For example, Trey, Grant Holloway, and Asier Martinez all won medals this year in Eugene, yet they are very different hurdlers with different race strategies and strengths. It could be tempting to encourage a hurdler to be more like Holloway in a race, as he’s the athlete closest to the world record right now, but I don’t think that would work for Trey.

I think it’s important to have athletes play to their strengths. Of course, you have to cover all the requirements of the event, but spending too much time addressing a weakness can be like banging your head against a wall. So, while we try and minimize those weaknesses, we focus on the strengths, as that’s what makes the athlete who they are and able to compete at their level. For example, Trey is naturally fast, and I think it is possible to get him to run very close to 10 seconds flat over 100 meters—therefore, his training is fairly similar to that of a sprinter. I think people may be surprised at how little he hurdles.

Referring to my previous answer, Trey raced about every other week throughout the 2022 season. If it was a race week, he obviously hurdled in competition; if it wasn’t a race week, he hurdled once that week in training, and that would be it. On the other hand, Ryan Brathwaite needed to hurdle a lot, which was reflected in how frequently we addressed that in the training plan.

Freelap USA: Tempo running is, I think, an often confusing and misunderstood training modality. What do you see as the benefits of tempo running, and how do you fit it into your training program?

Matt Kane: I think tempo has become very polarized. There are some coaches who hold the opinion that we never want to run as slow when racing as we do in a tempo session, so therefore it’s not worth doing. Meanwhile, there are other coaches who have tempo as the meat and potatoes of their training plan. I pride myself on being balanced in my approach to preparing sprinters and hurdlers, so we do tempo, but I don’t prioritize it to the same extent I do with sprinting.

Tempo running can provide a certain level of fitness that doesn’t necessarily help with the quality of a single workout in isolation so much as the recoveries between workouts, says @killakane_fsu. Share on XI think tempo running can provide a certain level of fitness that doesn’t necessarily help with the quality of a single workout in isolation so much as it helps with the recoveries between workouts, which allows for a consistently higher quality of training sessions through a long-term training period. I tend to prescribe the bulk of my tempo workouts on the grass, as it does reduce the impact slightly yet still places adequate stress on the tissues around the feet and ankles to elicit strength and conditioning adaptations.

While the velocity of a tempo run isn’t comparable to competition velocities, I don’t think in itself that that’s a reason not to do that type of work. Similarly, there are other exercises I, and probably a lot of other coaches, use that don’t simply replicate what we do in competition.

For example, I tend to include a good amount of lateral work or turning movements in general preparation because I believe it contributes to overall athleticism. Many of the guys I coached at the collegiate level played football or basketball in high school and were exposed to these movements, but that is not so common among the girls I coached in college. Therefore, having them do these movements is a way I can develop their foot, ankle, and hip strength and make them more athletic.

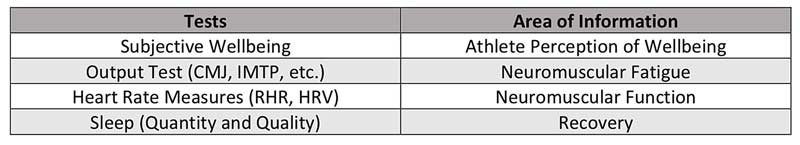

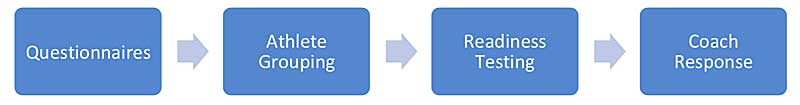

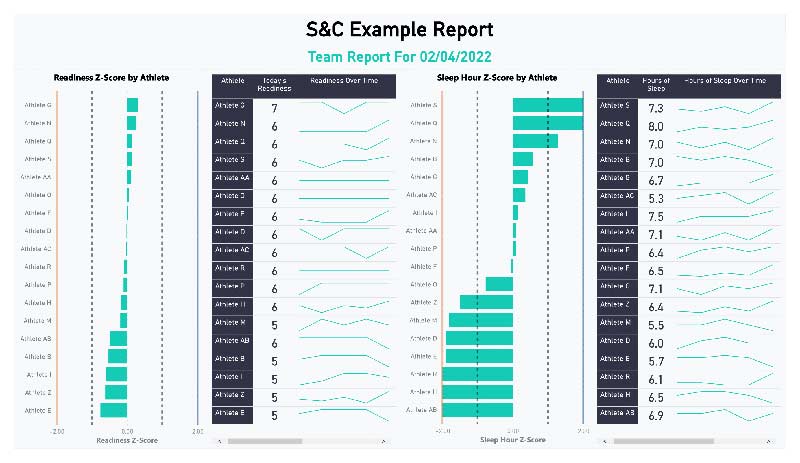

Freelap USA: Do you have any key workouts for your short sprinters that act as an indicator as to whether they are ready or not to compete well?

Matt Kane: I don’t have one particular workout that I use to assess an athlete’s readiness, but I am constantly monitoring. It’s important to know the athlete you are working with and their relative strengths and weaknesses, as the barometer may differ for different athletes. For example, when I was coaching Michelle Lee Ahye, just before she ran 10.82, she ran a 150m in 15.8 (hand timed) and went under 36 seconds for a 300m. However, while Ramona Burchell competed in the same events, a 300m time trial wouldn’t allow me to draw the same conclusions, so I tended to look more at a 150m and a 60m fly for her.

When attempting to extrapolate training data and predict what it may mean for competition, I try and involve the athlete in the process as much as possible. I think this is important for two reasons. First, it gives them the opportunity to understand my logic, and this requires honesty and transparency on my part, which can foster a positive coach-athlete relationship by helping to develop trust. Second, it gives the athlete ownership of the process as well. If they understand why a particular metric or workout may be important, then it can increase their buy-in.

When attempting to extrapolate training data and predict what it may mean for competition, I try and involve the athlete in the process as much as possible, says @killakane_fsu. Share on XNone of this is a strict science, and x in training will not always correlate to y in competition. Part of the reason for this is that some athletes perform relatively better in training than in competition, and vice versa. As I get to know an athlete better and get more data on them, I can factor this into any predictions I may make with them about what I think they are capable of doing on race day. This process can also serve as a diagnostic tool and flag challenges that athletes may face in competition.

While I can give broad advice on managing a competitive mindset, I think it’s important to stay in your lane and know when to reach out and get more specialized assistance. Also, along the lines of diagnostic tools, the data from workouts and races can be used to help optimize future training prescriptions.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF