A half-century ago, there was a universal approach to getting strong. Bodybuilders, weightlifters, and powerlifters performed many of the same lifts and often competed in the other disciplines. Arnold Schwarzenegger, for example, was as strong as he looked, bench pressing 441 pounds and deadlifting 683 in competition. Track and field throwers and football players soon discovered the benefits of pumping iron, and sports journalists became fond of asking NFL linemen, “How much can you bench?”

The nature of sports is that on many levels, “talent prevails,” which is why college athletic programs devote so much attention and money to recruiting. It’s also true that champions can become champions without ever setting foot in a weight room. A baseball player can lead his team in RBIs without pumping his biceps with curls, and a basketball player can become an MVP without doing a single squat. Further, some types of weight training can harm athletic performance. For example, putting a distance runner or a figure skater on the same muscle-bulking workouts that Arnold used to win his seven Mr. Olympia titles is probably not a good idea.

With velocity-based training, the quality of movement is more important than the quantity of weight, so it’s not a question of how much you can bench but how fast you can bench. Share on XThis brings us to velocity-based training (VBT), where the quality of movement is more important than the quantity of weight. From a VBT approach, the question to be answered is not “How much can you bench?” but “How fast can you bench?”

Header photo by Viviana Podhaiski, LiftingLife.com

12 Pioneers of Velocity Training

The following dozen individuals were chosen for their influence on getting strength coaches on board with velocity training. Let’s get started.

1. Yuri Verkhoshansky

Sports scientist Yuri Verkhoshansky is credited with developing a form of advanced plyometrics known as “shock training,” publishing his first article on the subject in 1964.

A track coach specializing in the jumps, Verkhoshansky attempted to duplicate the lower body stress in the various track events indoors by having his athletes perform heavy quarter squats. Working through a partial range enabled these athletes to lift considerably more weight than they could in conventional squats, often two to three times as much. Unfortunately, using such weights created excessive stress on the lumbar spine, and Verkhoshansky’s athletes complained of back pain. His solution was to experiment with a more intense form of plyometrics that didn’t overload the spine.

What distinguished Verkhoshansky’s plyometrics from conventional jump training was that the concentric movement (i.e., leg extension) was preceded by a relaxed state and involved a mechanical “shock.” Stepping off a low platform (so that the quads are relaxed) and immediately rebounding is an example of shock training. This approach enabled the tendons to act as biological springs, quickly releasing the stored elastic energy that developed during the landing. To learn more, invest in a copy of Supertraining by Verkhoshansky and Dr. Mel Siff, along with the more practical book Verkhoshansky wrote with his daughter called Special Strength Training Manual for Coaches.

The problem with shock training is that U.S. coaches often underestimate the stress of this training and don’t understand how to condition the body for it. This causes injuries, particularly overuse injuries, and often poor results. One former U.S. shot put champion told me he tore a patella tendon doing box jumps.

2–4. Alexander S. Medvedyev, Arkady N. Vorobyev, and Robert A. Roman

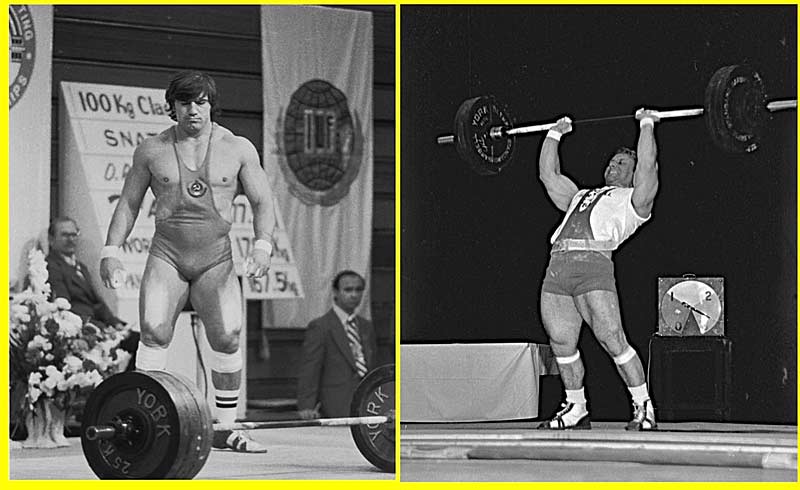

The translations of these three popular weightlifting sports scientists, among others, gave us insight into the optimal weights to use for explosive training. Unlike powerlifting or strongman, where an athlete has much longer to display their strength, weightlifting requires strength to be displayed as rapidly as possible.

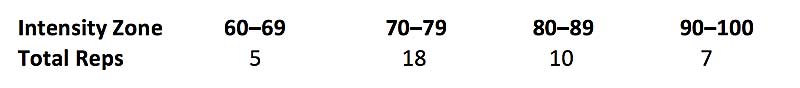

In weightlifting, the amount of weight used in relation to a lifter’s 1-repetition maximum (1RM) determines the intensity. Thus, if a lifter’s 1RM squat is 100 pounds, 100 pounds is 100% intensity. A lift of 85 pounds, no matter how many reps the athlete performs, would still be 85% intensity. These training intensities would be organized into intensity zones. Each zone focused on a different aspect of training. Higher intensities developed strength, and lower intensities developed explosiveness.

The primary intensity zones were divided into 10% increments, such as 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, 80–89, and 90–100. Let’s say a coach is planning workouts for the squat for a month. Not counting sets performed with less than 60% of the 1RM, let’s say the coach decided to prescribe 40 reps. They might distribute the repetitions in this manner:

As a weightlifter progressed, they would perform more lifts in the higher-intensity zones. Whereas a novice lifter might perform only two reps in the 90–100 zone in the clean and jerk in a month, an advanced lifter might perform seven reps. This approach parallels that of sprint coach Charlie Francis, who focused more on higher-intensity workouts with his elite athletes.

For the Olympic lifts, the coach would look at the ratios of these lifts to the squat to determine where to focus their repetitions. It’s a question of balance between strength and speed. If an athlete had a high squat in relation to their clean and jerk, the coach might prescribe lower-intensity squats so they could put more effort into performing an increased number of heavier clean and jerks. If their clean and jerk result was close to their results in the squat, they might perform an increased number of higher-intensity squats.

The Olympic press was a standing press that used the abdominal muscles to help thrust the weight overhead. After the 1972 Olympics, the lift was dropped from competition, leaving the snatch and the clean and jerk. The press was considered an “equalizer” in weightlifting, such that slower but stronger athletes could develop a big lead in the press to make up for a relatively poor showing in the snatch. This new emphasis on speed over strength resulted in significant changes in program design, and many inherently strong athletes gravitated toward powerlifting and strongman competitions.

5. J. J. Perrine

Perrine is credited with developing an isokinetic device that controlled the speed at which a resistance was lifted. This type of exercise was called “accommodating resistance,” such that the trainee could exert maximum effort through the full range of the concentric contraction. Isokinetics became a popular form of resistance training in rehabilitation, as the user could immediately reduce the resistance or safely stop if they experienced discomfort.

The significance of isokinetic training to VBT was that it confirmed the theory that force production is speed-specific. Share on XThe significance of isokinetic training to VBT was that it confirmed the theory that force production is speed-specific. In studies on swimmers, training at slow speeds produced changes in strength at slow speeds but not at high speeds. Training at high speeds increased strength at all speeds, but training at slow speeds produced the greatest strength increases at slow speeds.

For athletic fitness training, consider that acceleration is a component of power. Isokinetic machines do not allow you to accelerate the resistance, thus reducing power. There is also no eccentric component in isokinetic training. Canadian strength coach and posturologist Paul Gagné has studied velocity training extensively, applying this research to his elite athletes. “One problem with isokinetic training is there is no eccentric resistance, which is essential to use the elastic components of the tissues effectively.”

6. Carl Miller

Miller earned a master’s degree in exercise science and was a remarkable weightlifter and coach. He was appointed as the head coach of the 1978 U.S. Weightlifting team at the World Championships and coached weightlifter Luke Klaja when he earned a place on the 1980 U.S. Olympic team. Miller also “walked the talk.” After enduring two spinal fusions by age 41, Miller snatched 281 pounds and clean and jerked 352 pounds! Twenty years later, he cleaned 319 pounds and ran 4.91 in the 40-yard dash.

Miller visited Bulgarian Weightlifting Head Coach Ivan Abadjiev to learn about their training methods, as that country had become a weightlifting powerhouse. Abadjiev athletes won 12 Olympic gold medals and 54 World Championships. In a training camp I attended in 1977, he discussed a unique way that weightlifters could increase their lifting speed.

Power is the amount of work done in a specific amount of time (technically: Power = Force x Distance / Time). Another way to look at power is that it measures the most effective force in athletic movements. Miller cited a force-velocity chart with a vertical “Y” axis representing force and a horizontal “X” axis representing velocity. He said maximum power would equal 50 percent of maximum speed and 50 percent of maximum strength.

Miller suggested that weightlifters who needed to increase their lifting speed would benefit by performing lifts such as power snatches and power cleans at one-half their 1RM. The problem with weightlifting is that the barbell is the sport, and lifting 50% weights doesn’t translate into the technique used with heavy weights. In many Eastern European weightlifting textbooks, weights less than 70% are often not mentioned in workouts since they are considered a warm-up. (Funny story: During a seminar he gave in Rhode Island a dozen years ago, I asked Abadjiev about using submaximal weights to increase barbell speed. He replied, “I don’t want my athletes to lift light weights fast—I want them to lift heavy weights fast!”)

Although Miller’s 50% method didn’t catch on in the weightlifting community, Louie Simmons popularized high-speed training with his “dynamic effort” workouts for powerlifting and sports training.

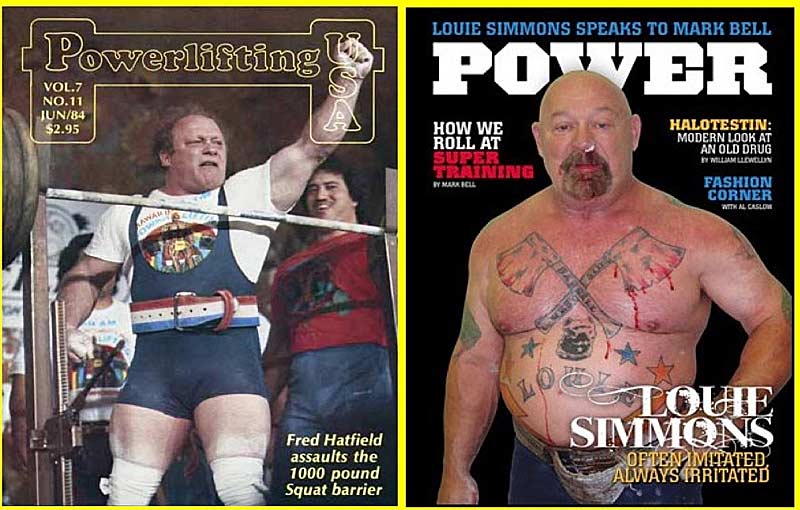

7. Louie Simmons

One of the most influential coaches in powerlifting was Louie Simmons of the famous Westside Barbell Club. The key to his success was a workout system called Conjugate, which involved using various training methods every week to avoid plateaus. He called one of these methods “dynamic effort,” which involved moving moderate weights as fast as possible.

Louie Simmons believed that focusing on high-velocity training methods in the lifts would enable powerlifters and other athletes to become more explosive. Share on XBesides dynamic effort workouts, Simmons experimented with chains and bands to increase explosiveness. Although the power lifts are performed relatively slowly compared to the Olympic lifts, Simmons believed that focusing on high-velocity training methods in the lifts would enable powerlifters and other athletes to become more explosive. (For more on Louie Simmons, check out the documentary Westside Versus the World, available on Amazon.com.)

8. Fred Hatfield, Ph.D.

Fred “Dr. Squat” Hatfield was a college professor who squatted 1,000 pounds in 1987. (FYI: The first to squat 1,000 was Lee Moran, who did this at the USPF Senior Nationals in 1984). In 1982, Hatfield introduced the concept of “Compensatory Acceleration,” which entails increasing overload by moving as quickly as possible. He believed athletes would develop maximum power if they thought about moving quickly, even if the weight moved slowly.

9. Ian J. King

Although he hasn’t received the exposure of other strength coaches, Australia’s Ian King produced many thought-provoking books and other resources about strength coaching. King is credited with developing a three-digit formula for prescribing movement speed in weight training exercises. This formula got strength coaches thinking about lifting speed.

Using a bench press as an example, a 421 tempo prescription would mean you would lower the barbell to your chest in four seconds, pause at the chest for two seconds, then press the bar to extended arms in one second. An “X” would mean “as fast as possible.” Thus, 42X means you would press the bar off the chest as fast as good technique allowed.

Later, King’s formula was expanded to four digits by Canadian strength coach Charles R. Poliquin, with the fourth digit representing the pause in the advantageous leverage position (such as when the barbell is held at extended arms in the bench press). Thus, a 42X1 formula for the bench press would mean you would rest for one second with the bar at extended arms before starting another repetition.

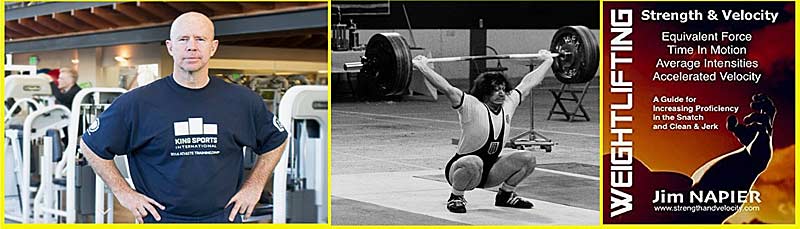

10. Jim Napier

Napier was a U.S. weightlifting champion who broke four American records and competed in the 1977 and 1978 World Weightlifting Championships. He wrote several books on velocity training, explaining why speed should not be sacrificed for weight in weightlifting. One comment that summarizes Napier’s ideas is, “I don’t care how much you squat, but how much you can squat in one second!” (I should add that Dr. John Garhammer did pioneering work over four decades ago measuring power in many lifts. For example, he found that the power production for a jerk was nearly five times greater than a back squat or a deadlift.)

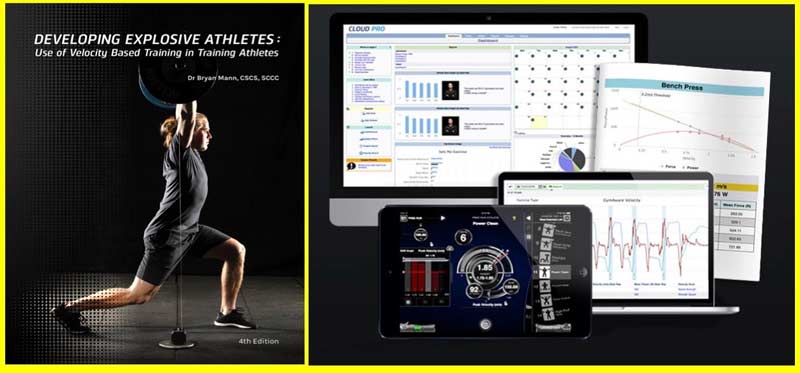

11–12. Scott Damman and Bryan Mann, Ph.D.

We should credit these two coaches/sports scientists for helping to popularize velocity-based training, particularly using devices such as GymAware that measure bar speed. In addition to conducting practical research on velocity-based training, both Damman and Mann have promoted VBT methods in speaking presentations as well as articles and podcasts available via SimpliFaster.

Damman & Mann helped popularize a modern approach to velocity training that associated specific intensity ranges with a type of strength. The nature of a sport determines which velocity range to use. Share on XWith this modern approach to velocity training, specific intensity ranges are associated with a type of strength. Drawing from the Bosco Strength Continuum, a load (relative to a 1-repetition maximum) of 15%–40% would focus on starting strength, and a load of 80%–100% would focus on absolute strength. For example, in the off-season, athletes would perform more lifts in a slow-velocity zone; as the season approached, athletes would perform more work in a fast-velocity zone. Here are the zones, progression from slowest (>1.3 m/s) to the fastest (<0.5 m/s):

- Absolute strength

- Accelerative strength

- Strength-speed

- Speed-strength

- Starting strength

The nature of the sport would also help determine which velocity zone was used. For example, most football linemen should focus on developing absolute strength more than a wide receiver or a quarterback. That is, they might perform many of the same core lifts in a workout but at different training velocities. VBT can also be used to precisely assess an athlete’s physical preparedness.

Consider the bench press, a universally recognized predictor lift for American football. In the NFL Combine, the 225-pound bench press for reps is the standard for determining a player’s upper body strength and power. The official record of 49 reps was set by defensive tackle Stephen Paea, suggesting it is primarily a muscular endurance test. Because high-rep bench pressing is ballistic (with the athlete bouncing the bar off their chest), it can be quite harsh on the shoulders. Alternatively, an athlete can perform the VBT bench press test to measure upper body power more precisely.

To review, with the Eastern Bloc training systems used by weightlifters, percentages of the 1RM determine how much you lift. The problem is that some days you can perform better than others. Consequently, the prescribed weight could be too light or too heavy, especially since strength performance can vary daily. With velocity-based training, you can test the velocity of the bar throughout a workout to determine how much weight you should use for a specific workout. According to researchers such as Andrew Fry, it can also be used to determine overtraining, which affects power.

Many others have contributed to modern strength training methods, but these 12 individuals should be acknowledged for helping to “change the game” of athletic fitness training. Before closing, let’s look at how VBT influenced the head strength coach of an Ivy League college.

VBT in Action

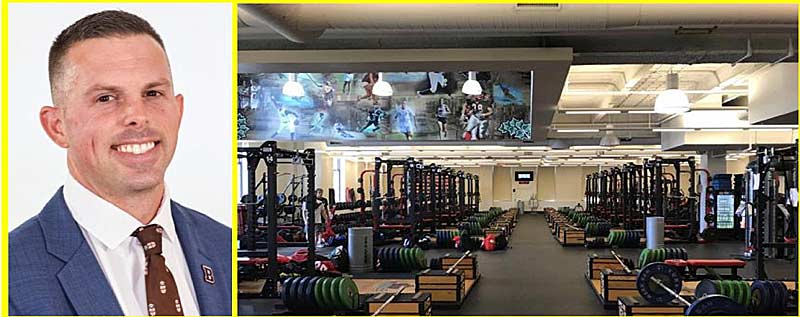

Brown University Head Strength and Conditioning Coach Brandon O’Neall oversees the training of 1,200+ athletes in 36 varsity and 12 club sports. About 75% of his athletes use VBT. Here’s his story.

“I was introduced to VBT in 2003 when I played football at Central College in Pella, Iowa,” says O’Neall. “Our strength coach, Jake Anderson, came to us from the University of Iowa and implemented their training regimen with us. He brought with him a Tendo unit—he only had one—and was doing some interesting research on measuring barbell speed, rather than relying on reps, percentages, or asking, ‘How does that feel?’”

Beyond the numbers, O’Neall found that one of the primary benefits of using VBT was seeing how it motivated his athletes. “Instead of going into the workout with the attitude to lift more weight than the person next to them, their approach would be, ‘I want to move this weight faster,’ and get immediate feedback with the VBT units.”

Building on Hatfield’s concept of Compensatory Acceleration, O’Neall says VBT provides a form of competition for his athletes to go into a workout with the ‘intent’ to lift quickly. Share on XBuilding on Hatfield’s concept of Compensatory Acceleration, O’Neall says VBT provides a form of competition for his athletes to go into a workout with the “intent” to lift quickly. “You can’t underestimate the value of competition. Take sprinting—you’ll run a lot faster if you race against someone than if you run by yourself.” O’Neall also has science on this side, as several studies found that providing immediate feedback on jump squat performance produced superior results in the standing broad jump and sprints performed for distances of 20 and 30 meters.

In 2011, O’Neall joined the Brown coaching staff when the school finished its new weight room, the Zucconi Strength and Conditioning Center. When it came time to purchase equipment, he told the administration that having a VBT unit at every do-it-all lifting platform in his gym was critical. “I’ve been to places that had velocity training devices and those that didn’t, and it’s really tough to replicate the type of workouts I wanted my athletes to perform if you don’t have the immediate feedback, those measurements, the VBT provides.”

Asked if it was a challenge to implement VBT at Brown, O’Neall replied, “Our athletes are smart. They know that speed of movement is critical—it’s not just how much you can lift. You tell them how to utilize VBT, adjust their rep scheme based on the parameters we provide, and they do it.”

Squats and bench presses are among the most popular lifts performed with VBT units, but O’Neall expanded his VBT toolbox by using it with static and countermovement hex bar jumps. The hex bar is more stable than dumbbells (and the dumbbells tend to bang against the thighs, causing bruising) and provide a better anchor for the VBT ripcord. It’s a good idea.

Squats and bench presses are among the most popular lifts performed with VBT units, but O’Neall expanded his VBT toolbox by using it with static and countermovement hex bar jumps. Share on XWhile you can use the VBT training unit alone, such as when performing a squat to get feedback about bar speed, O’Neall says his coaching staff has used it in combination with other technologies. For example, a volleyball player would perform a hex bar deadlift and immediately test their vertical jump on a force platform. This type of contrast training stimulates more fast-twitch muscle fibers to be recruited on the jump (through post-tetanic potentiation). It also provides the athlete with another feedback loop to determine if the weight should be increased or decreased on the next set.

One unique use of VBT at Brown is testing when the athletes return from summer or winter break. Coaches often perform max testing to see if their athletes have been training, giving insight into who is serious about making the team. This approach may add injury to insult, as those who have not been training hard may be at a greater risk of getting hurt with 1-rep max testing. Rather than maxing, O’Neall uses a submaximal percentage of their athlete’s max for squats and bench presses, so they are less likely to injure themselves but test their best results in bar velocity.

“Some athletes may not have access to good training facilities during their break. That’s unfortunate, but I don’t want to put them in a position where they are further behind physically with an injury or mentally by embarrassing them with 1-rep max testing,” says O’Neall. “I’m not here to bring the wrath of Hell upon these athletes on their first day back—I want to provide them with an atmosphere they are excited to be a part of. Yes, they don’t always enjoy all the hard work we put them through, but they reap the benefits of what we have them do and become excited about their progress.”

Finally, O’Neall uses VBT to determine physical preparedness before and after competitions, particularly with football players. “If someone is moving a weight really fast, let’s load them up! If they are moving slower than normal, we back off. In a football game, one athlete may take 60 snaps and the other only 10, but both played that day. We play on Saturday and lift on Sunday, and VBT can help us determine the optimal weights to use based on their fatigue level.”

Other strength coaches may do more or less than O’Neall does with VBT technology, but all have relied on the work of the Iron Game pioneers recognized here. Further, VBT units have progressed beyond the ripcord methods that attach to a barbell to three-dimensional, wireless technologies that are more user-friendly. It’s an exciting time to be a strength coach!

Weightlifting textbooks from the Eastern Bloc mentioned in this article are available through sportivnypress.com. Books by Dr. Mel Siff and Yuri Verkhoshansky are available through Amazon.com.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Fry AC, Kraemer WJ, van Borselen F, et al. “Performance decrements with high-intensity resistance exercise overtraining.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1994;26(9), 1165–1173.

Garhammer J. “Power Production by Olympic Weightlifters.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1980;12(1):54–60.

Hatfield F. “Getting the Most from Your Reps.” NSCA Journal. 1982;4(5):28–29.

Jones K, Hunter G, Fleisig G, Escamilla R, and Lemak L. “The Effects of Compensatory Acceleration on Upper Body Strength and Power.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 1996;10(4):287.

King IJ. How to Write Strength Training Programs: A Practical Guide. 1998, King Sports International.

Randell AD, Cronin JB, Keogh JW, Gill ND, and Pedersen MC. “Effect of instantaneous performance feedback during six weeks of velocity-based resistance training on sport-specific performance tests.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2011;25:87–93.

Takano B. Weightlifting Programming: A Winning Coach’s Guide. 2012; pp. 54–59. Catalyst Athletics, Inc.

Weakley JJS, Till K, Read DB, et al. “Jump Training in Rugby Union Players: Barbell or Hexagonal Bar?” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2021;35(3):754–761.

Thanks for a very good article that hopefully will help coaches to use VBT in the future

Stepping off a low platform and immediately rebounding was in use in Germany and Poland ten years before Verkhoshansky experiments…

Thanks for the comment. Can you give me a published, dated reference from researchers in those countries that I can research to compare their work with the classical plyometrics (i.e. shock training) from Yuri Verkhoshansky’s? I’ve never seen anyone challenge Verkhoshansky’s claim that he was the creator of classical plyometrics. Fun Fact: Dr. Siff told me the East Germans had teams of researchers translating the work of Russian sports scientists such as Professor Verkhoshansky.

It all begins with a statement by Tadeusz Starzynski, Polish jumping coach, in his “Le Triple Saut”, Editions Vigot, 23 rue de l’ Ecole de Medecine – 75006 Paris, 1987. On page 120 of this publication Starzynski states :

“La plyometrie est connue depuis longtemps et pratiquee dans l’ entrainement des triple sauteurs polonais depuis 1952”

Continuing my research, I found an old German manual, author Toni Nett, dating back to 1952.

The title was “Das Ubungs und Trainingsbuch der Leichtathletik”, Verlag fur Sport und Leibesubungen Harry Bartels, Berlin Charlottenburg 5, Fritschestrasse 27/28. In the section dedicated to the triple jump, the exercises using depth jumps with rebound appear

Already in 1962 Mr. Tadeusz Starzynski had published a manual on the triple jump, where he presented the methodologies already used for a long time in Poland (including depth jumps with rebound).

The title was Trojskok, Seria popularnych podrecznikow lekkiej atletyki, pod redakcja Jana Mulaka, Sport i Turystyka, Warszawa 1962.

This publication is in my possession and I can send you a copy.

This is why I played it safe and used the title “A Brief History….” “Rather than “The Brief History.” 🙂

The goal of the article was to recognize a few of those Iron Game pioneers who helped with the evolution of athletic training – I’m sure I left many other deserving individuals out.

With what you’re presenting, we could say that Verkhoshansky did extensive research on depth jumps and helped popularize this form of training in sports other than track and field. That said, your references are intriguing.

In “Supertraining,” the athletic fitness textbook Verkhoshanky co-authored with Dr. Siff, there is an extensive reference list. However, even though Verkhoshanky was a jumps coach, there are no references to the publications you listed. How could he have missed this?

This information will come in handy next time I write an article about plyometrics.

Kim

P.S. Thanks for the offer to share a copy. First, I’ll see if I can find those references through my resources first.

There’s more : Track Technique – The Journal of Technical Track & Field Athletics, Fred Wilt Editor, no 17, September 1964

Heinz Rieger, Training of Triple Jumpers. The article was translated and synthesized by Gerry Weichert from no 8 issue of “Der Leichtathlet” dated June 6 1963. Rieger was coach of the ASK Vorwarts Club in East Berlin ( former DDR).

Several Depth Jumps exercises are presented in this very old article.

Track Technique – The Journal of Technical Track & Field Athletics, no. 20, June 1965

Heinz Kleinen, Winter Conditioning and Training for Triple Jumpers

Translated by Jess Jarver from no 4, January 28 1964 issue of Die Lehre der Leichtathletik, published in Berlin, West Germany

Several depth jump drills in this article.

In short, in Poland, West Germany and East Germany, Depth Jumps with rebound had already been known and practiced for a long time

Good stuff! I’ll be sure to refer to this material in future articles I write about plyometrics when appropriate.

It also could be argued that gymnasts practiced depth jumps long before Verkhoshansky published any of his research. Again, the best compromise seems to be that Verkhoshansky popularized applying many training methods from track and field to other sports. Oh, and that he had a better publicist! 🙂

Thanks again for the references!

I would like to point out that the Germans, during the execution of the depth jumps, used mats, precisely because of the very strong impact on the ground, very similar if not equal to the “shock” method (and we are in 1950 – 1951).

Hi Mr. Goss. You should look into Juan José Badillo work too. He is a spanish professor and reseacher, and maybe the most well versed person on VBT. And I think he deserves to be credited in this post in my humble opinion.

You can check one of his publications over here :

https://scholar.google.es/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=es&user=xmX0Wq4AAAAJ&citation_for_view=xmX0Wq4AAAAJ:q3oQSFYPqjQC

Badillo’s contributions to VBT research would be good for a Part II, and I’m looking forward to seeing his books translated into English. The focus of this article was to recognize some of the early pioneers in this area.