Injuries are much more than just damage to the body: the cascade of disruptions extends far beyond the field of play and can reach into many facets of life. For many athletes, being injured not only means they’re off the field, but it can also threaten their sense of meaning and personal identity, social network, general life rhythms, and in some cases, even financial stability.

Breathing strategies are not just a great way to enhance the direct rehabilitative outcomes desired during return to play (RTP), but they also can help athletes regain a sense of control and emotional stability while they surmount the many challenges that can accompany unplanned time off from training or play. Due to the central placement of breathing in human psychophysiology, thoughtful use of breathing strategies can help athletes in a holistic way that can enhance the RTP journey across the board.

Because breathing is a nearly universally implementable strategy, it can be deployed with success both inside and outside of standard training and play environments. Share on XBecause breathing is a nearly universally implementable strategy, it can be deployed with success both inside and outside of standard training and play environments. There are opportunities inside more formal environments like training facilities or clinics where breathing exercises can be used for pain relief during treatment or as an efficient way for athletes to stay in shape. Additionally, athletes can use takeaway protocols outside these formal spaces to enhance sleep and recovery or manage pain.

This article will discuss some of the simplest ways to positively impact the return to play experience as well as offer insight for coaches, athletic trainers, and therapists who may be helping to guide the healing process.

State and Stress Management – A Holistic Effect

As an athlete thinketh, so shall they be. Managing the internal state of mind during return to play is no small part of the picture. Injury and the attached mental and emotional stress can test our stress management skillset. As coaches, we often chirp about mindset and attitude, but what tools can we offer our athletes when they are at their lowest?

Discussing concepts like attitude, mindset, and resilience with our athletes is important in general but especially during RTP. Due to the fluid and fleeting nature of how we think and feel, it can be challenging to anchor onto and create a palpable change. A distinct advantage of using breath practices during return to play is that it turns the challenge of modulating internal dialogue into a physical skill. This gets the athlete out of their head and into their body.

Using breath practices during return to play turns the challenge of modulating internal dialogue into a physical skill. This gets the athlete out of their head and into their body. Share on XIn addition to the obvious physical healing process for the injured athlete, the application of breathing techniques during return to play doesn’t just plug holes in the proverbial dam; it can also be an opportunity to examine and bolster shortcomings in their mindset. Breathing techniques can play an indispensable role in this process. The development of enhanced carbon dioxide tolerance, for example, has direct implications for bolstering general resilience due to its effect on deep autonomic physiology.

Of course, the athlete and their team must generalize these lessons to both the return to play process and the chosen field of play. With that said, there is robust research that supports not just the reduction of anxiety (a serious issue in RTP) but, more essentially, the enhancement of overall mental resilience.

Practical Application

There are multiple protocols in the course of this article that are multipurpose in their deployment. For the sake of brevity, I’ll mention two of the techniques described in more detail later in this article and how you can implement them for general stress management and readiness.

These two types of breathing do not serve every athlete with 100% efficacy, but they cover the bases for most and can be deployed without concern of doing harm.

Athletes having trouble managing stress can use either of these two protocols to bookend their day. Five minutes in the morning upon waking and five minutes before bed isn’t too big of an ask and generally gets the job done. Additionally, they can be used to keep the stress bucket from overflowing as needed throughout the day. Even a minute or two can turn the tides of a bad day. Using metrics like heart rate variability and resting heart rate for autonomic tone as well as emotional reactivity can be helpful in better understanding acute changes and trends as a result of using these breathing strategies.

It’ll take a bit of experimentation to get it just right, so be sure to listen to individual responses. If an athlete reports that one protocol works better for them than the other, heed the call. You wouldn’t drive off a cliff just because Tom says to turn right, so don’t get stuck in sunk costs here, either.

Pain Management

Pain is one of the most authentic experiences we can have, and when we are having it, most of our attention goes toward making it stop. Thinking about pain a bit more clearly can help us not only make sense of the entire injury experience but also deploy pain relief and recuperative strategies more effectively.

Having an accessible and reliable tool like breathing at their disposal means athletes in the RTP process feel an enhanced sense of control over their experience of that process. Additionally, other pain management strategies can be costly in time and money. Some, especially pharmacological interventions, may come with a host of side effects that then need to be dealt with on top of the original issue. Breathing strategies are zero cost and have the side benefits of a more balanced nervous system and improved mental state.

Having an accessible and reliable tool like breathing at their disposal means athletes in the RTP process feel an enhanced sense of control over their experience of that process. Share on XThere are two main components to how breathing can reduce the pain experience for the athlete. The first is to normalize hyper-aroused states of the nervous system, which we covered in the previous section on state and stress management. Heightened sympathetic activity, especially in the form of anxious dread (heightened negative emotion about what might happen), has been shown to exacerbate pain responses. It’s been demonstrated, for example, that burn victims anticipating the sting of treatment were more sensitive to pain, but a slow breathing protocol prior to treatment reduced their anxiety (arousal) and made them more receptive to the intervention.

This logic can be used for relief in athletes experiencing anxiety related to the pain or discomfort associated with therapeutic interventions or movement protocols. Reduction in the fear response will calm some of the body’s protective mechanisms and can help with improved integration.

It can be challenging to separate the effects of breathing on general relaxation from pain relief. However, some studies have shown that slow breathing does have a measurable and significant effect on pain reduction, specifically. The precision with which protocols can be separated from one another and their subsequent outcomes relies mostly on contextual cues from both athlete and practitioner. With that said, if any tool creates a reduced pain experience and enhances the efficacy of RTP protocols to no negative net effect on the athlete, by all means, we should use it.

The majority of the research work on this topic has been on slow deep-breathing techniques. However, I would be remiss if I failed to mention promising avenues that use purposeful acute hyperventilation techniques, also called superventilation, that have potential in pain relief as well. Techniques in this category, like the very popular Wim Hof Method, have been shown to release adrenaline into the body during their use. During these states of purposefully increased arousal, pain signals can be suppressed. There are two significant downsides, however.

- There can be underlying conditions that these kinds of techniques can exacerbate to dangerous effect (anxiety and panic disorders, for example).

- Superventilation techniques can present a kind of false ceiling for tolerance in the RTP environment and, as a result, contribute to distorted awareness on the part of the athlete.

A preponderance of studies tells us that achieving six breaths per minute (one breath every 10 seconds) for about five minutes can reduce the sympathetic drive for most people. With that said, there are a few ways to skin this cat, and athletes can respond differently to the application of these protocols.

Here are a few that athletes can try immediately before RTP-based sessions or in the morning before coming to practice/therapy.

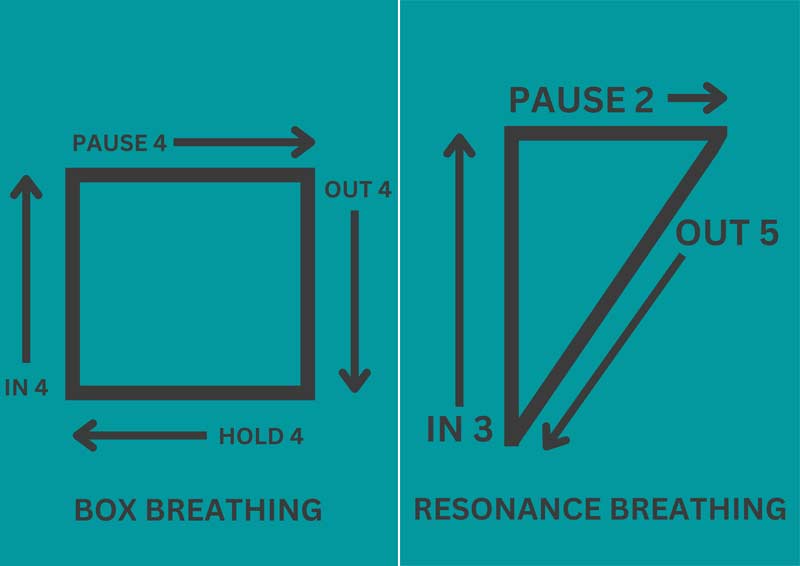

Box Breathing

Box breathing is an equal ratio of inhale:pause:exhale:pause. So, to achieve six breaths per minute or less, we would do 3:3:3:3. Technically, this is five breaths per minute, but you get the point.

Resonance Breathing

I mentioned this one in my previous article about breathing for recovery, and it applies quite nicely here too. Resonance breathing synchronizes the heart and lungs together to achieve a sort of neurological “tuning”—hence, resonance. It’s also easy to do and remember.

Simply repeat the below sequence for the allotted time:

- Inhale for three seconds.

- Pause for two seconds.

- Exhale for five seconds.

**Note: Athletes who have underlying anxiety may not like prolonged breathing phases. It’s best to let the athlete determine which of the protocols works best for them based on how they feel as long as they’re getting about six breaths/minute.

Improved Recovery

Along the same axis as state management are the improved recovery benefits of breathing techniques during return to play. Recovery is always an essential focus during training and competition, but it moves from coach to first-class seats during RTP. Specific breath training used both immediately before and/or after therapeutic inputs can go a long way toward enhancing recovery from the stress of rebuilding. Therapy places the athlete in structurally and neurologically vulnerable positions, and breathing strategies can help the body return to a more parasympathetic state so more complete healing can occur.

Therapy places the athlete in structurally and neurologically vulnerable positions; breathing strategies can help the body return to a more parasympathetic state so more complete healing can occur. Share on XPractical Application

Pre Session

Breathing techniques deployed pre-session can help an athlete find a state of autonomic equilibrium, especially if they tend to be anxious about the session in general or anticipate unwanted pain and discomfort.

As a general rule, preparing somebody for work by having them lie down and do something relaxing can be self-defeating, but in this case, it’s necessary. The following protocol can be used for two to three minutes to quell the demons and get the athlete into a more receptive state of mind.

Simply instruct the athlete to:

- Sit comfortably with support as needed.

- Breathe using slow, controlled nasal breaths.

- Find a sweet spot where the exhale is slightly longer than the inhale. (This may take a few breaths.)

I purposefully did not provide a numbered protocol here because this is an opportunity for the athlete to learn to tune their own system. If they come into the session a little too amped up, and the protocol delivered right before doesn’t mesh with their internal mechanisms, it can be aversive and potentially exacerbate their attitude toward the session and breathing techniques as well.

Post Session

After the training/therapy session is over, there’s a bit more leeway. If the session was particularly challenging, have them relax in a comfortable position and use a 3:2:5 (inhale:pause:exhale) for three to five minutes. This use of resonance breathing helps harmonize the autonomic nervous system. Additionally, you can amplify the effects by having the athlete body scan during breathing. If they find a place where they’re holding tension, they can gently squeeze and relax the area during the two-second pause.

Before Bed

Athletes who sleep better recover better—period. However, pain and positional sensitivity can disrupt sleep for athletes in RTP and potentially interfere with ideal healing. Performing slow and controlled nasal breathing in bed (without a screen!) can help slow the car down on the way to the intersection rather than just slamming on the brakes. This will set the nervous system up for a successful transition to sleep. As a bonus, athletes who wake from discomfort overnight can also use this as a go-to for helping them get back to sleep or at least suffer less from sleep anxiety.

There are lots of options here. It’s up to you as the practitioner to listen to the needs of the athletes in your care and deploy the solution you feel best solves the problems you and your athlete face—and what’s more, the one the athlete will actually do!

Use During Therapeutic Intervention

Biology has two prime directives: survive and replicate. In that vein, the job of your nervous system is first and foremost to protect—to protect you from outside harm and to protect you from, well, you. It’s obvious when you say it out loud, but many rehabilitative strategies fail to take this first principle into account and, consequently, get limited results or contribute to other surreptitious compensatory processes.

Breath constraints during the application of movement rehabilitation techniques or skillset reintroduction give practitioners direct insight into how the nervous system receives the prescribed inputs in real time. Remaining ignorant of these subtle hints won’t necessarily interfere with achieving results altogether, but it can certainly limit efficacy and precision.

The opportunity to have a deeper dialogue with the athlete about how their body is adapting to the inputs is not to be scoffed at. The perception of high performers regarding both their interpretation of discomfort and personal readiness is often skewed. Hurry up and get back to normal so “I can be me” is a common sentiment that builds a house of cards ready to collapse at the next breeze.

Slow nasal breathing with good breath mechanics is a great indicator light for practitioners and offers athletes a way to self-regulate during especially challenging tasks during return to play. Share on XSlow nasal breathing with good breath mechanics is a great indicator light for practitioners. At the same time, it offers athletes a way to self-regulate during especially challenging tasks during return to play. This time can be especially frustrating for athletes, and providing a goalpost is conducive to a more robust healing outcome. This keeps athletes from taking a “task completion” attitude toward the process. Along with that, it’s important to educate them as to why they are breathing this way. Hold them to the standard, and don’t let them skate!

Practical Application

A slow, smooth, and full nasal breath is a beautiful force multiplier in RTP for athletes and coaches and a good place to start when applying therapeutic inputs. Asking an athlete to maintain purposeful breathing keeps the autonomic nervous system from going into overdrive. This can mean more meaningful results during the session because the nervous system feels safe.

More often than not, when targeting especially challenged tissues or ranges, athletes grind through the exercise from one breath hold to another. These apneic events are a clear sign from your nervous system. Back off half a step and be a little nicer. Effort is good, but precision is better.

In some instances where novel or especially challenging interventions are being used, there can be cause for purposeful exhalation from the mouth. You should pay attention to cringing, gasping, wheezing, huffing, puffing, panting, or otherwise involuntary adverse reactions to the stimuli and generally avoid them. Return to play is not an outlet for the prowling sadism of coaches or therapists. Be precise and do no harm.

Deviations from these standards don’t necessarily mean you need to jump ship on the RTP approach you’re employing, but it does allow for a more precise reconciliation of the neurological message of “don’t do that” and intelligently pushing thresholds. There are some obvious cases where you’re dancing on the edge of what the athlete can manage in the moment. In those cases, deliberate exhales through the mouth can be particularly helpful in modulating arousal responses that exacerbate pain, avoidance, and compensation.

The key word in the previous sentence is deliberate. Deliberate activation of breathing muscles lights up a higher part of the brain and keeps the athlete in an attentive response state rather than a reactive one.

During high challenge/pain potential, use slow, smooth nasal breathing as much as possible. Unconscious deviation during execution shows a change in neurological tolerance. When dancing on thresholds of progress, deliberate exhalation can help manage the pain response in real time.

When dancing on thresholds of progress, deliberate exhalation can help manage the pain response in real time. Share on XSimple Simon

All of this is not to say that if you don’t integrate breathing strategies, you won’t get results from RTP. We know that’s not the case. But using these strategies thoughtfully, you can get more precise indications of protocol success, at least neurologically, and therefore be more precise with your outcomes.

There are many opportunities to integrate breathing techniques into return to play processes. You don’t have to and may never use them all. Keep it simple, Simon. Find what works for your style of coaching/rehab and dovetail the tools appropriately. Regardless of where and when you integrate breath control into your RTP approach, it’s most certainly a powerful force multiplier that will enhance your existing toolkit and enrich the athlete’s experience.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Resources

Jafari H, Gholamrezaei A, Franssen M, et al. “Can Slow Deep Breathing Reduce Pain? An Experimental Study Exploring Mechanisms.” The Journal of Pain. 2020;21(9–10):1018–1030.

Busch V, Magerl W, Kern U, Haas J, Hajak G, and Eichhammer P. “The effect of deep and slow breathing on pain perception, autonomic activity, and mood processing—an experimental study.” Pain Medicine. 2012;13(2):215–228.

This article shares some practical info that may be enough on its own or a launchpad for deeper work. I like that it was research based and not immediately trying to sell a service; right in line with what James Nestor writes about. I wonder what strategies you have for athletes RTP who have undergone major trauma