This episode of Facility Finders rolls into the Grove to meet up with Riley Allen. Coach Allen is the Assistant Strength and Conditioning Coach at the University of Mississippi (Ole Miss), working with basketball. Both basketball teams use this recently renovated space at Ole Miss; located near the basketball pavilion, the facility allows for streamlined training and the ability to do that right before or after practices and games.

Design

This facility is a 2,200-square-foot space with a renovation completed in 2021. Many collegiate coaches across the country aim to have a weight room featuring open space and every piece of equipment needed to train their athletes. Coach Allen wanted the same thing, but because of the size of the existing space, the Ole Miss weight room needed to be the Swiss Army knife of equipment.

This means all of their pieces of equipment are arranged in about a 64-square-foot area. The low-profile racks are my favorite pieces in this weight room because of their ability to save the limited square footage, approximately half of the size of Trinity College’s weight room, without sacrificing quality or customization.

“We had to renovate an existing space,” Coach Allen noted. “So the dimensions of the room dictated a lot of that.”

This idea from Coach Allen is something many coaches forget. By this, I mean coaches always want to design their “Taj Mahal” but should instead focus on upgrading their existing space and making it more accessible and useful. One way to do that is to invest in quality equipment that does more than one thing and can fit in one small area instead of using two pieces of equipment that take up extra space. Open space is king, and this room has that—many times, coaches try and win the arms race that is total square footage for their facility but don’t think about the need for OPEN space.

Coaches want to design their ‘Taj Mahal’ but should instead focus on upgrading their existing space and making it more accessible and useful. Share on XCoach Allen utilized Samson for his equipment needs. The racks here contain weight stacks on their columns and a lat pull/low row combo off the back, which gives them more floor space to move and train in. The room also has a strip of turf that can be used for warm-ups, sled pulls, and plyo exercises; on the other side of that is another auxiliary space. Coach Allen decided to have the bumper plates all match to save space and present a customized look for athletes touring on recruiting visits.

Purchasing

Customization. Relationship. Cost. Reputation. Durability. Ole Miss decided to find the company that checked off these key qualities that Coach Allen needed, and Samson did just that for them, especially with the way their rep worked alongside Coach Allen during this renovation.

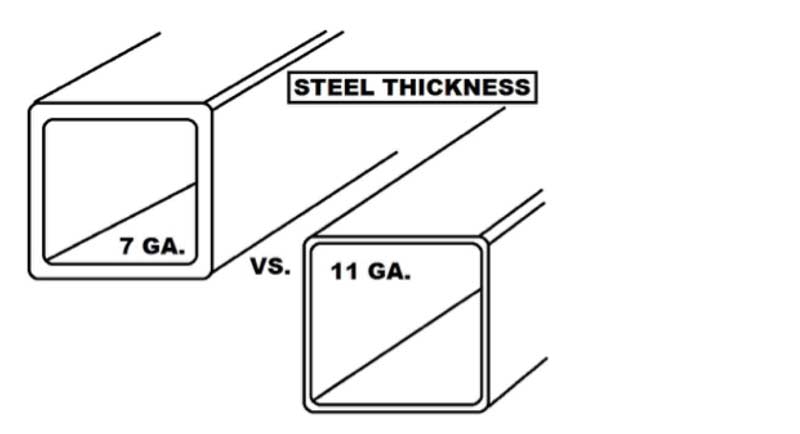

One thing that Samson’s racks have that others don’t is the 7-gauge steel they use instead of the typical 11-gauge. The difference is the durability and reputation achieved here by the nearly three-times thick wall that is 7-gauge steel, making it much stronger against clanging bars and plates.

Customization is something that small spaces must have; for instance, the customized low-profile racks up against the wall at Ole Miss and also the cable columns that don’t take up any more space. This renovation was crucial for Ole Miss, not only for their athletic development but also for their recruiting needs as an SEC basketball team. Every corner of this room has the school’s branding to help attract the nation’s best recruits and coaches to the school.

Besides Samson equipment, Ole Miss purchased Keiser squat machines and PowerBlock dumbbells. These pieces continue the theme of maintaining a small footprint but having a massive number of uses. The PowerBlocks enable teams to have a whole rack of dumbbells in one small area instead of taking up a larger footprint. They are adjustable and expandable, and their more compact shape lends to taking up much less room than the standard.

Specialty Equipment

Of course, Ole Miss has specialty equipment too, and some pieces worth noting are the flywheels, lat pulldown/low row combo, resistance cables that attach to the ground, VALD ForceDecks, and Eliteform VBT. These pieces are what Coach Allen says help set apart the training the Rebels do in the weight room from teams throughout the rest of the country.

The lat pulldown/low row is attached to the rack without taking up a large amount of space. The sports science pieces from VALD and Eliteform are used to help track athlete performance to make sure the training is doing what the program is supposed to—by this, I mean if Coach Allen is training for elasticity during a specific block, then he can use this technology to track the athletes’ Relative Strength Index (RSI) or the eccentric velocity of their lifts to make sure the program is achieving those goals.

Coach’s choice to incorporate specialty equipment and technology in a smaller area was probably challenging. The purchases have to justify the space they take up (since space is king), but these have so many different and important uses that I think it was worth it.

Finally, the attachable resistance cables that are inlaid into the floor are very creative. Again, this means they don’t require racks to have band pegs or Vertimax setups because they are built into the floor. The cables can be used on the bars in the racks or attached to the athletes on the platform. Many coaches don’t know that having inlaid resistance cables is an option, but if you communicate what you want to equipment companies, those companies will typically either have or make a solution for those needs.

Takeaways from Coach Allen

This basketball facility was designed with an eye toward providing all the training needs for basketball athletes in a small 2,200-square-foot facility. It’s hard sometimes to get everything you want or need for training, especially across many teams, when, for instance, basketball teams might need to train on taller racks or coaches may need multiple exact sets of things to accommodate their athletes.

When I asked Coach Allen his thoughts on the whole project, he stated:

“Take your time. Get samples and put your hands on them. Put them in the same light the room will be if possible. Redesign several ways. Share your thoughts with other coaches and get feedback.”

Coaches should know that these equipment companies want you to try out their product because they are confident it will speak for itself. Take them up on that. Share on XSomething many coaches forget is that these equipment companies want you to try out their product because they are confident the product will speak for itself. So, it’s important to actually take them up on that because you might quickly find how much you hate/love what makes their product special.

Also, go and see other facilities done by the companies you are interested in. Talk to those coaches and get their points of view on what they like/dislike and if they would change anything if they were to do it again.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF