[mashshare]

Nitrates are inorganic compounds found in a wide range of vegetables, most prominently in beet roots and leafy green vegetables. Their chemical structure consists of a nitrogen atom bound to three oxygen atoms.

For years, many health practitioners recommended that people avoid consuming cured meats, citing the nitrate content as one of the main reasons. This is because in many processed foods nitrates are often found as nitrosamines, which are linked to some adverse side effects. However, the nitrates found mainly in vegetables are naturally occurring and may have potential health benefits.

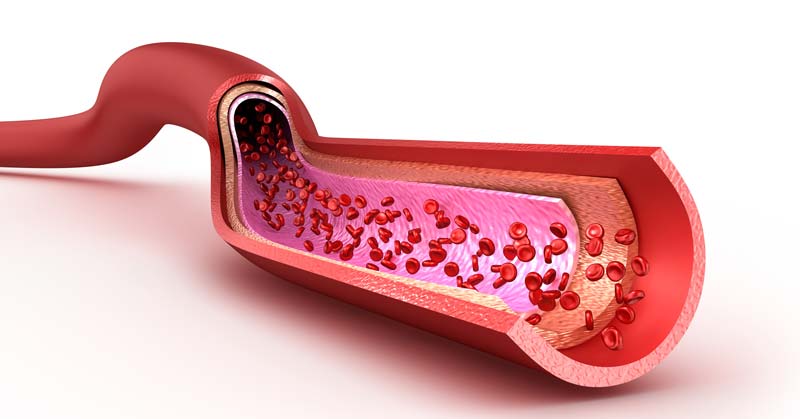

In recent years, nitrates have come to prominence in the sports nutrition world because of their popularity with elite endurance athletes. When nitrates are consumed, they get converted to nitric oxide, which is a potent vasodilator aiding in oxygen transport. Exercise scientists have linked nitrate consumption in studies to a variety of ergogenic benefits, ranging from an increased proportion of type 2 fiber to improved performance during repeat sprint intervals to increased power output.

Nitrates, Nitrites, and Nitric Oxide

Dietary nitrates get converted to nitrites by bacteria in our saliva, as well as by specific enzymes in specific tissues. Nitrites can then get further metabolized to nitric oxide through several different pathways. Nitric oxide is a signaling molecule that plays a role in the vasodilation (widening) of blood vessels, which results in increased blood flow. Increased blood flow during exercise and at rest has been linked to increased performance and recovery.

Some beneficial attributes of increased plasma nitric oxide levels are increased exercise-induced skeletal muscle glucose uptake and a reduced oxygen cost during exercise. For high intensities, increased glucose uptake is a beneficial attribute, as this is the primary (and fastest-acting) energy source during these types of activities. This makes it a beneficial attribute for most field sports where there’s a requirement, at various times, to kick into a higher intensity gear.

Similarly, a reduced oxygen cost during exercise is a major benefit for field sports, as a reduction in this factor results in a higher degree of efficiency. Some research indicates nitrates can positively influence the mitochondria’s phosphate/oxygen ratio by increasing it. In more practical terms, by increasing the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) ratio and producing more ATP, we can produce much more energy since all movement is ultimately fueled by ATP.

What the Research Shows

Fiber Type: Type I fibers are known as “slow twitch” fibers. They’re the slow oxidative fibers that are beneficial for endurance performance and they’re the fiber type we typically rely on the most throughout daily activities. Type II fibers, or “fast twitch” fibers, are associated with explosive contractions and are the fiber type typically sought for athletes that participate in speed-based sports.

Many speed/power training programs are built around maximizing the proportion of type II fibers. It’s typically thought that this fiber type proportion is a product of genetics and that training style can influence it to some degree. However, one study shows that nitrate administration might also be of benefit.1

The effects of sprint interval training (SIT): SIT in normoxia vs. SIT in hypoxia alone or in conjunction with oral nitrate intake was investigated to view the buffering capacity of homogenized muscle and fiber type distribution, as well as its influence on sprint and endurance performance.

Twenty-seven participants were divided into three groups: 1) SIT in normoxia with a placebo; 2) SIT in hypoxia with a placebo; and 3) SIT in hypoxia with a nitrate supplement. All three groups participated in five weeks of SIT on a cycle ergometer (30-second sprints with 4.5 minutes of recovery between intervals for three weekly sessions of four to six sprints per session). Nitrate (6.45 mmol NaNO3) or placebo capsules were administered three hours before each session. Before and after SIT, participants performed an incremental VO2max test, a 30-minute simulated cycling time trial, and a 30-second cycling sprint test. Muscle biopsies were taken from the vastus lateralis.

The relative number of type IIa fibers increased in the nitrate supplement group but not in any of the other groups. Compared with hypoxia, SIT tended to enhance 30-second sprint performance more in the nitrate supplemented group than in the hypoxia group.

SIT in hypoxia combined with nitrate supplementation increased the proportion of type IIa fibers in the muscle. When nitrate supplementation was provided during SIT in hypoxic conditions, relative type IIa fiber numbers increased from 45% to 56%.

Enhancing Work Rate

The ability to sustain a high work rate is an underrated aspect of sports performance, especially when discussing the topic of speed. While the energetic systems will vary within and across sports, there’s variance on a position-by-position level. For instance, field sports greatly reward athletes with higher work rates.

One of the most promising effects of nitrate supplementation is its ability to enhance work rate… Share on XThe ability to sustain explosive speed throughout the course of an event is crucial for many athletes, and this can be a deciding factor between playing time and riding the bench. One of the most promising effects of nitrate supplementation is its ability to enhance work rate in the form of reduced fatigue during higher intensities and better performances on repeat sprint interval measurements.

A study investigated the effects of dietary nitrate supplementation on exercise performance and cognitive function during a prolonged intermittent sprint test (IST) designed to reflect typical work patterns during team sports.2 Sixteen male team sports players received 140ml of NO3-rich beetroot juice or NO3-depleted placebo beetroot juice for seven days. On day 7 of supplementation, the subjects completed a sprint test consisting of two 40-minute halves of repeated two-minute blocks consisting of six seconds of all-out sprints, 100 seconds of active recovery, and 20 seconds of rest on a cycle ergometer during which cognitive tasks were simultaneously performed.

Total work done during sprints on the IST was greater in the beetroot group compared to placebo and the reaction time of response to cognitive tasks in the second half improved in the beetroot group compared to placebo. The findings suggest dietary nitrate enhances repeated sprint performance and may attenuate the decline in cognitive function. Specifically, it affects the reaction time during prolonged intermittent exercise.

In a double-blind randomized crossover design, 14 recreational male team sports players were assigned to consume 490ml of concentrated nitrate-rich beetroot juice and nitrate-depleted placebo juice over 30 hours preceding the completion of a Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test.3 The resting plasma nitrite concentration was 400% greater in the beetroot group compared to the placebo. Performance in the Yo-Yo IR1 was 4.2% greater with beetroot juice compared to placebo (this equaled 1,704 m vs exercise-induced 1,636m). These findings suggested that NO3 nitrate supplementation may promote nitric oxide production and enhance Yo-Yo IR1 test performance.

Another study assessed whether a high-nitrate diet could increase nitric oxide bioavailability and evaluated its effect on exercise performance.4 This randomized crossover study tested seven male subjects before and after a six-day high-nitrate diet vs. a control nitrate diet (8.2 mmol per day vs. 2.9 mmol per day, respectively). Plasma nitrate and nitrite concentrations were significantly higher in the high-nitrate diet group compared to control.

The high-nitrate diet group showed a significant reduction in oxygen consumption during moderate-intensity constant work rate cycling. They also had significantly higher total muscle work during fatiguing, intermittent submaximal knee extension, and improved performance in repeated sprint ability tests. The finding suggested a high-nitrate diet could be a feasible and effective strategy to improve exercise performance.

How Power Output Is Modulated

In sports settings, a high level of power output is probably the most desirable physical attribute and, as a result, it is one of the talents for which athletes are most compensated. We see evidence of this with power hitters in baseball, deep threat wide receivers in football, and knockout artists in boxing.

In most sports, power production is a more-lauded skillset than strength or size. There are even performance measurements suggesting that higher levels of power output correlate with better sports performance, as evidenced by improved sprinting or jumping numbers. A traditional way to increase the potential for power output has been to increase dietary or supplemental creatine intake. Research shows that another potential strategy is to increase nitrate consumption.

Acute NO3 supplementation can enhance maximal muscle power in trained athletes. These findings may particularly benefit power-sport athletes who perform brief explosive actions.5

Acute nitrate supplementation can enhance maximal muscle power in trained athletes. Share on XIn the case of nitrate supplementation, its impact on increased power output is also relative to the VO2 max ratio, meaning that in studies subjects can increase their power output while maintaining the same energy cost. Examples of this are the aforementioned studies on nitrates and repeat sprint performance. Not only is the amount of power output increased, but it’s increased without having a costly effect on the energy systems. This allows athletes to perform higher quality work without compromising volume. This also contrasts with the typical way of increasing power output in training, where, as power output increases, energy costs tend to increase and total volume decreases.

About Responders and Non-Responders

While a lot of positive research and anecdotal evidence shows that nitrate consumption can have benefits for sports performance, the results aren’t unanimous. A study on club-level cyclists performing a 50-mile time trial after supplementing with beetroot juice did not result in a significant improvement in time trial performance.6 The authors of the study suggested it was possible that the training status of the cyclists (well-trained) limited the effect compared to what some studies have shown on moderately trained cyclist tests.

Another thing of note from the study was that participants who saw the greatest increases in plasma nitrate had improved performance whereas others in the study had little change in plasma nitrate and no improvements in their performance. Similarly, another study was done on the effects of dietary nitrates on repeated sprint performance in team athletes and the subjects saw no improvements in performance.7 The authors in this study acknowledged that they did not measure changes in plasma nitrate.

These studies open up the possibility that other variables, like training status and response to dietary nitrate load, can impact the efficacy of this protocol.

The Best Nitrate Sources

One major advantage of nitrates that makes them unlike many other lauded nutritional ingredients (e.g., turmeric) is that their dietary bioavailability is extremely high, at an average of 100%. The most well-known source of nitrates are beets but, fortunately, there are other sources high in dietary nitrates if beets aren’t your thing. A few things to take note of regarding dietary nitrate sources is that the nitrate content can vary over the course of the year because of factors like the season and soil quality.

Uncooked foods are some of the highest sources, which is the reason juices are a popular method to supplement nitrates. Another important note is that nitrates get converted to nitrites by beneficial bacteria found in our saliva, so you’re advised against brushing your teeth or using mouthwash immediately after consuming dietary nitrates.

Some high dietary nitrate sources include: celery, arugula, beetroot, spinach, Chinese cabbage, kohlrabi, leeks, parsley, dill, radish, bok choy, cabbage, fennel, cress, and savoy cabbage. It can be also found in smaller amounts in other foods like carrots, broccoli, cucumber, turnips, and pumpkin.

Nitrate Loading Guidelines

There are a variety of loading protocols for dietary nitrates, ranging from very acute (a few hours prior to competition) to a sustained daily amount over the course of several weeks. The ranges used in studies typically vary from 300-600mg of nitrate. Peak plasma nitrate levels are typically reached 1.5 to 1.8 hours after consumption.

Two things to consider when implementing any dietary/supplement strategy:

-

Dose at the lower end of the spectrum and slowly work your way up. Using this strategy allows you to maximize the minimal effective dosage of any nutrient. More isn’t always better and, in certain instances, a tolerance can be built up quickly or it can be detrimental. With certain nutrients that have dose-dependent responses, you can start out on the lower end of the dosage spectrum to maximize its effectiveness and see continual benefits as you increase the dosage. However, if you start at a high dosage the ceiling for improvement is limited.

-

Experiment with nitrate loading prior to competition. It’s never a good idea to attempt new things too close to competition. This is good general rule to keep in mind for any supplement/dietary protocol. For instance, with dietary nitrates, some individuals report GI distress as a side effect.

It’s better to fuel your body with familiar foods prior to important competitions, rather than experimenting with new things. This means that some strategies to experiment with nitrate loading could occur during the off-season. Or, for certain individuals that participate in multiple events throughout the year, experiment during a season when the events are less important.

Nitrate Loading Very Acute Protocol

Two common dosage protocols for acute nitrate dosing are: 1) one to two hours pre-competition as a single dosage, and 2) splitting the dosages at the two- and one-hour marks prior to competition. After you’ve experimented with nitrate loading, and if you find that your athlete is a positive responder, this very acute protocol can be an ideal method in situations where you’re working with that athlete late into their training camp with an event fast approaching. As a nutritionist, this situation is sometimes common with combat athletes, where some don’t make dietary changes until the last few weeks (or in some instances, week) before a fight.

Nitrate Loading Acute Protocol

A semi acute loading protocol can also involve increasing dietary nitrate intake during the week of competition. This can range from a single daily dose to more common splits of two or three doses of 300-600mg per day. With this protocol, plasma nitrate is temporarily peaked during competition week. This can be a very feasible compromise in instances where some athletes already have ritual game day meals that they don’t want to deviate from or where adherence to a more chronic dosing will likely not be followed.

Nitrate Loading Chronic Protocol

A chronic protocol is another commonly used loading method that’s done over the course of several weeks. Often the dosage range during this protocol will be split up into two or three dosages per day of 300-600mg total. This loading protocol is an effective method to promote an overall dietary change, because in many instances it results in athletes consuming a large amount of leafy green vegetables.

Further Suggestions

Nitrates are available in a variety of dietary sources, with beetroot juice being the most popular dietary/supplemental form. In studies, it’s been used both acutely (a one-time dosage a few hours before an event) and chronically (over the course of several weeks). The exercise parameters by which it’s been measured include different types of aerobic and anaerobic protocols, ranging from measuring longer distance time trials to short distance sprint performances using modalities such as sprinting and cycling. The potential benefits for athletes interested in increased speed include increased type II fiber proportion, improved performance during repeat sprint intervals, reduced fatigue at higher intensities, and an increased power output.

While there are promising results with dietary nitrate administration, some studies have showed no improvements from supplementation. Given that some of the richest dietary sources include highly nutritious vegetables like beet root, arugula, Chinese cabbage, and spinach, it could be worthwhile for athletes to experiment with increasing their dietary nitrate intake. Dosage ranges in studies have varied from 300mg to 600mg, which is an attainable number through diet alone.

References

-

Smet, S. D., Thienen, R. V., Deldicque, L., James, R., Sale, C., Bishop, D. J., & Hespel, P. (2016). Nitrate Intake Promotes Shift in Muscle Fiber Type Composition during Sprint Interval Training in Hypoxia. Frontiers in Physiology,7. doi:10.3389/fphys.2016.00233

-

Thompson, C., Wylie, L. J., Fulford, J., Kelly, J., Black, M. I., Mcdonagh, S. T., et al. (2015). Dietary nitrate improves sprint performance and cognitive function during prolonged intermittent exercise. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 115(9), 1825-1834. doi:10.1007/s00421-015-3166-0

-

Wylie, L. J., Mohr, M., Krustrup, P., Jackman, S. R., Ermιdis, G., Kelly, J., et al. (2013). Dietary nitrate supplementation improves team sport-specific intense intermittent exercise performance. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 113(7), 1673-1684. doi:10.1007/s00421-013-2589-8

-

Porcelli, S., Pugliese, L., Rejc, E., Pavei, G., Bonato, M., Montorsi, M., et al. (2016). Effects of a Short-Term High-Nitrate Diet on Exercise Performance. Nutrients, 8(9), 534. doi:10.3390/nu8090534

-

Rimer, E. G., Peterson, L. R., Coggan, A. R., & Martin, J. C. (2016). Increase in Maximal Cycling Power With Acute Dietary Nitrate Supplementation. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 11(6), 715-720. doi:10.1123/ijspp.2015-0533

-

Wilkerson, D. P., Hayward, G. M., Bailey, S. J., Vanhatalo, A., Blackwell, J. R., & Jones, A. M. (2012). Influence of acute dietary nitrate supplementation on 50 mile time trial performance in well-trained cyclists. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 112(12), 4127-4134. doi:10.1007/s00421-012-2397-6

-

Martin, K., Smee, D., Thompson, K. G., & Rattray, B. (2014). No Improvement of Repeated-Sprint Performance with Dietary Nitrate. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 9(5), 845-850. doi:10.1123/ijspp.2013-0384