A local collegiate soccer coach referred one of her athletes to me to help alleviate the nagging hamstring pain she had been dealing with while sprinting. I have developed a reputation for helping athletes improve sprint technique, and this coach is savvy enough to know that technique influences both speed and function.

The athlete suffered what sounds like an undiagnosed grade I hamstring pull (a minor pull) about six months prior to beginning training with me. She told me in our first meeting that the injury hurt fairly badly at first but got better quickly.

“So, what’s the issue now?” I asked.

She then described the typical lingering problems many athletes experience after a hamstring pull.

“It only hurts when I start running fast,” she said.

“Does it hurt the whole time you’re sprinting or only when you get up to fast speeds?”

“Only when I get to fast speeds. My left side hurts worse, but I feel it on my right side too.”

“Can you describe it?”

“It’s like my hamstring wants to cramp,” she said. “And I think if I try and go faster, it will pull again.”

“I know that feeling exactly.”

I shared with her that in my junior year in college, I had a season-ending hamstring pull. My leg was black and blue from the bottom of my butt to mid-way down my calf, and I used crutches for a few days.

Perhaps due to incomplete rehab (which included no sprinting), it took me over a year to fully recover. The next season, I could only get to about 90% top speed before I started feeling that same grabbing, cramping sensation she described to me.

This was a point of connection for us, but also a point of hope, as I told her that I eventually got back to 100% despite feeling (like she did) that I might never get over it—and despite my injury being much, much more severe than hers.

For those fortunate enough to have never had a hamstring pull…you know the type of cramp where you feel your hammy tightening, but you’re able to straighten your leg quickly enough to stretch the cramp away before it fully seizes and REALLY starts hurting? That pre-extreme, you-better-straighten-your-leg-now-or-else phase is exactly what it feels like to sprint after a hamstring injury—except, instead of the cramp just getting tighter, your hammy will pop if you push it.

And I knew, just as she did, if I pushed it and ran faster, my hammy definitely would have popped again.

“I think I can help you with this. What does your timeline for training look like?”

It was Christmas break, and even though her college was only a few miles away, she would start classes and spring soccer soon. We had four weeks and one session per week to get her back to sprinting without limit.

I felt a certain amount of pressure, not only because I wanted to help this athlete, but because her coach had entrusted her to me. This was an opportunity to make-or-break trust with the coach and help the athlete get back to doing what she loved. A certain amount of my reputation was on the line.

I was a bit nervous.

Game on.

The Hamstring “Checklist”

I’ve presented factors that influence hamstring injury in full elsewhere. I reviewed that article while preparing for the athlete to ensure I covered all bases in my approach.

The following elements are expanded on in that article and constitute what I currently understand as the most important factors for preventing a hamstring injury:

- Sprint-specific mobility at the hamstring and hip (the Jurdan test)

- Sprint technique, with an emphasis on pelvic position

- Exposure to sprint volumes and high-velocity sprinting

- Joint angle-specific resistance training (hip and knee)

- Hamstring eccentric capacity

- Triceps surae strength

- Aerobic fitness

- Fearlessness*

“Fearlessness” has an asterisk because it wasn’t included in the article referenced above. That piece was written in the context of preventing injury for athletes who have never pulled a hamstring: essentially, training advice.

In this case—working with an athlete who has had a hamstring injury but is still dealing with lingering issues—fearlessness is a critical factor and deserves a seat at the table, says @KD_KyleDavey. Share on XIn this case—working with an athlete who has had a hamstring injury but is still dealing with lingering issues—fearlessness (a term I first heard Carl Valle use in relation to performance) is a critical factor and deserves a seat at the table.

Indeed, the mental aspect of recovering from injury doesn’t get enough attention, but it was important to me that she know and feel confident in her ability to sprint, as opposed to simply having the physical capacity to do so. I share the subtle ways I nudged her toward confidence and away from fear later in this article.

Likewise, since writing that first article, I took Derek Hansen’s two online courses, the second of which is specific to sprint-based return to play strategies for hamstring pulls. The course significantly influenced my ability to program effective return to play sprint progressions and upgraded my understanding of sprint kinematics and how to instruct them (my first exposure to which came from the ALTIS foundation course). It also provided several drills along with the knowledge of the “why” and “how” to implement them with success. Perhaps most importantly, Derek’s course gave me more confidence that I could actually help this athlete.

Here’s how I pulled it all together and helped her overcome her hammy issues in just four sessions.

Four Weeks to Freedom: The Game Plan

Four one-hour training sessions are not very much time, and neither are four weeks in the context of changing performance. But improvement is certainly possible in that time frame, and I wanted to help this athlete get back on the field without restriction.

So, what did I do?

Referencing the list above, I asked myself what I could and could not affect in four hours spread across four weeks. Fortunately, the athlete loves working out in the gym, is a competent lifter, and agreed to let me write her programming. She requested six days per week of exercise, including the one session she had with me, which I was happy to provide.

This arrangement allowed us to focus solely on sprint kinematics and the mental aspect of the injury during our sessions and attack the other factors in the gym throughout the week.

Our evaluation on day one was quick and dirty, as I didn’t want to eat a quarter of our time together in testing. I did, however, want to understand if she had the requisite mobility to allow for acceptable sprint technique, see and film her sprint, and collect baseline sprint times.

We performed two mobility assessments: the Jurdan test and a simple ankle mobility screen that can be seen here.

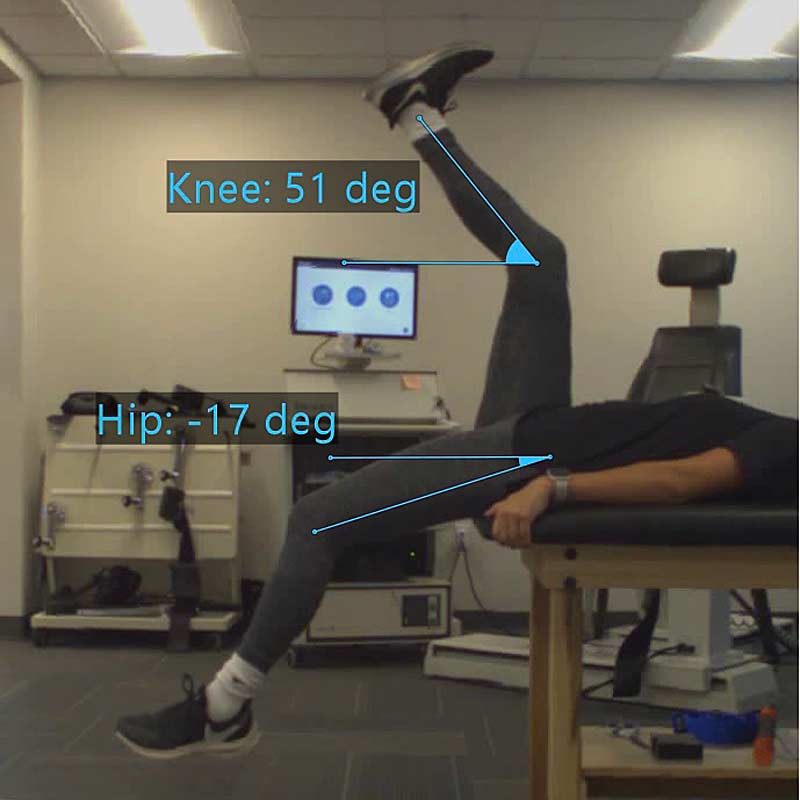

The Jurdan test, named for its originator, Jurdan Mendiguchia, is a sprint-specific mobility screening that assesses knee and hip range of motion. For a detailed description of how to administer and score the test, see this and this.

After the mobility screenings, I watched, filmed, and timed her sprint, instructing her to go as fast as she was comfortable and confident with.

Luckily, her mobility was great, so we spent no time improving her range of motion whatsoever.

Her sprint technique, however—well, as they say, a picture is worth a thousand words.

This athlete has a reputation for being fast, so I was surprised and pleased to see such a poor technique. If you’re surprised to hear I was pleased to see it, the reason is simple: it gave clear direction and a very obvious “thing we need to work on.”

This is also where we began reframing her mental state. As mentioned above, I knew she was anxious and nervous about running fast because she could feel her hamstring grabbing and cramping when she approached high speeds: the warning sign not to run any faster or else it may pop.

If, on the one hand, I had told her after our first session, “I don’t see anything wrong, but I think lifting and sprinting will help. Yes, you’re right, you’ve already been lifting, but not on my programming…and yes, sprinting is what causes the pain, but trust me, it will help….”

That would have been true, but it doesn’t sound reassuring. It’s like taking your car to a mechanic and being told, “The diagnostic didn’t turn up anything wrong but just bring it back, and I’ll change the oil. I’m pretty sure that should fix the loud banging you hear while driving.”

Instead, I was able to tell her with confidence that her technique wasn’t ideal—which she clearly recognized when viewing the film—and share my confidence that changing her technique would help her speed and hamstring health.

I gave clear and positive expectations and set the stage for her to expect healing. Taking a note from the OPTIMAL theory of motor learning model from Wulf and Lewthwaite, I employed enhanced expectancies (“conditions that enhance expectancies for future performance”) to accelerate (no pun intended) not only motor learning but her general mood, affect, sense of hope, and disposition toward training with me in general—factors that I believe indeed influence motor learning.

This mental aspect cannot be understated. That she EXPECTED healing is paramount to the process of healing, says @KD_KyleDavey. Share on XThis mental aspect cannot be understated. That she EXPECTED healing is paramount to the process of healing.

Motor Control and Sprint Kinematics

Interestingly, as can be seen above, the athlete’s heel strike is more exaggerated on her left. She also reported that her left hamstring bothered her more than her right.

To me, this is a chicken-or-the-egg situation. Does her hammy bother her, in part, because of this technique? Or was this technique developed subconsciously to limit sprint speed as a protective mechanism?

An exaggerated heel strike like hers is often paired with an inflated contact distance (distance between the foot and center of mass upon touchdown). The first part of ground contact is a braking phase, where sprint velocity decreases, and the second part of touchdown is propulsion, where velocity increases. Ideally, propulsion and braking times are roughly equal, each about 50% of the step cycle.

A larger-than-necessary contact distance, crudely assessed via shin angle upon touchdown (the shin should be near vertical), increases the time spent braking, causing slower sprints. Heel striking also limits, if not completely disregards, the stretch-shortening abilities of the Achilles complex, further limiting speed.

An absent stretch-shortening cycle coupled with the foot striking far in front of the center of mass forces more work on the hamstring group, likely increasing injury risk.

I don’t have film of her sprinting pre-injury, so I’ll never know if the chicken or the egg came first.

We began with the A-series progression, also known as Mach drills. They are, essentially, maximum velocity mechanics, but at slow speeds. When properly progressed, I’ve found the series to be highly valuable, as it makes it easy for athletes to learn the feel and movement of proper maximum velocity technique.

We started with a simple A-march in place. The athlete was unable to maintain a vertical torso, or a vertical position in general, even with a simple march in place.

Video 1. Unbeknownst to her, the athlete leans forward and shrugs her shoulders with every march. If this motor engram is in place during marching, it may also rear its head while sprinting.

Interestingly, she couldn’t feel and didn’t notice that she was doing this. I took the video above so she could see it. After watching and talking through it, she understood the objective but still struggled to execute it effectively.

I recalled noticing during her warm-up at the start of the session that she struggled to posteriorly tilt her pelvis during one of the movements, which made me question her general ability to control her pelvis.

Having conscious control of the pelvis—being able to anteriorly and posteriorly tilt, as well as lateral tilting and circling for bonus points—is a central theme in sprint technique and, specifically, hamstring health. Lack of control often shows itself during the A-series and can contribute to the folding noticed in this athlete.

Having conscious control of the pelvis is a central theme in sprint technique and, specifically, hamstring health, says @KD_KyleDavey. Share on XSo, we backed up and worked this a little bit, following a general progression athletes consistently have success with. Unsurprisingly, she could not tilt her pelvis at first, and a basic deadbug was plenty challenging for her.

I stated briefly, in general terms, that sprinting with an anterior tilt isn’t good for a hamstring. I told her that as she learns to control her pelvis, she’ll be less likely to hurt when she sprints or have another injury, setting her up for mental success and expectations of wellness, healing, and performance.

With a little cueing and practice, she gained conscious control of her pelvis, and I pointed out how it was a good sign that she could conquer that so quickly. (As an aside, I genuinely believe this is one sign of a great athlete: the ability to learn or adjust motor skills quickly.)

Then we went back to the A-marches, where she was instructed to tilt posteriorly and remain vertical.

Like magic, her technique was much better, and again, I did not miss this opportunity to point out to her how well she was doing and how this was a significant step toward her goals.

Video 2. The differences between these marches are subtle but noticeable and important. The march on the right is more upright and has less extraneous movement in the back and neck, creating a crisper-looking and -sounding A-march. These new-and-improved mechanics can be leveraged and referenced to teach athletes how to sprint with proper technique.

From there, we could progress to traveling marches for distance, skips, and A-runs. These progressions sometimes seem tedious. Athletes (and perhaps coaches) may question their relevance/transference to sprint technique.

These drills are baby steps toward sprinting—essentially, maximum velocity mechanics at slow, controlled, and conscious speeds. Each progression is more dynamic and challenging than the previous one. If an athlete can’t march or skip with good technique, they likely can’t sprint with good technique.

As athletes build mastery at each level of the progression, they move on to the next. The final stage I typically use is an A-run that starts slow and gradually increases in speed, similar in nature to the dribble-bleed runs taught and employed by the folks at ALTIS.

Understanding and communicating that A-running is simply a top-speed technique, athletes are instructed to A-run slowly for a short distance—5 or 10 meters—and then gradually increase speed until they’re moving at about 75%–80% of top speed (subjectively). All the while, they must maintain the A-run technique (which, again, is good max speed mechanics).

Videos 3 and 4. Slow-motion footage of meters 10–15 of an A-run (3) and footage of the athlete sprinting on day one of our training (4). While not perfect, her A-run technique resembles ideal sprint mechanics much more closely than her actual sprinting did on day one.

This is a nice transition and gets athletes to feel max speed mechanics while moving at decent speeds. The athlete here picked up the technique relatively quickly and reported no hamstring pain or the grabbing sensation while sprinting with these ideal mechanics.

Knowing it had been months since she was able to run that fast without symptoms, I asked, “When’s the last time you’ve been able to do that pain-free?” She thought for a moment and then told me it had been months—confirming not only to me but, more importantly, to herself that she was well on her way toward healing.

This was a huge mental win that gave her confidence and hope.

Still, we limited speed to 80% subjective effort during the first two sessions to mitigate any risk of reinjury and give her body time to adapt to the stimuli delivered with these newfound mechanics.

Learning to transition from acceleration to max speed mechanics is a related skill, but it is distinct from simply starting in max speed mechanics (A-running) and speeding up with them. The athlete struggled to emulate her A-run technique during the upright phase of free sprints in her first two of four sessions, but she had a breakthrough in her third and figured out how to do so.

Her sprints started to look poetic instead of clunky and forced. Along with this poetry in motion, she felt no pain or grabbing/cramping sensations in her hamstring and no sense of fear or hesitation.

She felt she could dial up the speed a notch, and I agreed. I instructed her to bump her speed from 80% to 90% (subjective effort).

For the first time in months, she could sprint at that intensity without fear, pain, or hesitation. Again, this was highlighted immediately, confirming to the athlete that she was progressing and getting closer to sprinting without limitation.

Lifting and Sprint Progression

Including one session per week with me, the athlete requested to train six days per week. I was delighted to meet her request and provide such a program. Keeping in mind she is an athlete and needs to train like one—yet still needs to address her hamstring issues—I organized her sessions as follows and delivered them via FYTT:

Mondays and Tuesdays included a sprint progression that generally increased in volume and distance throughout the four weeks. Friday included a maintenance sprint workout.

The thought process behind the sprint progression (Monday and Tuesday) was heavily influenced by Derek Hansen’s return to play course mentioned earlier in this article. Two of the big-picture takeaways I gained from his course are not to be afraid of sprint volume and to program sprints early and often in the return to play progression.

Thought patterns from both strength and conditioning and physical therapy are combined: increase exposure (volume) and intensity over time to stimulate tissue healing and performance.

The complete progression I programmed is simple and detailed below:

Brain Games

Little bits on the athlete’s mental state and relationship with her hamstring pain have been sprinkled throughout this article. Similarly, tiny disruptions to that relationship were sprinkled in during our four weeks of training. She was always very positive and upbeat but did have a justified concern with and mistrust of her ability to sprint without risk of injury when we began working together.

- “You’re picking this up really quickly. Some people take weeks to get this down. That’s a great sign—you’re making progress fast.”

- “That rep felt better on the hammy? Awesome, that’s a step in the right direction and a sure sign that you’re making progress.”

- “Wow, you were able to run at 90% without feeling that grabbing sensation? That’s huge. When’s the last time you’ve been able to do that?”

- “Do you have any hesitation or fear going into this next sprint rep? No? Wow—how long has it been since you haven’t had to think twice about sprinting fast?”

True return to play includes not only the physical body but the mind and spirit as well. Simple gestures such as the above, delivered with timeliness and sincerity, are strong reinforcement to athletes they are getting better.

True return to play includes not only the physical body but the mind and spirit as well, says @KD_KyleDavey. Share on XReturn(ed) to Performance

By the end of our four weeks together, the athlete reported no physical discomfort, mental fear, or hesitation of any kind. At the time of writing, about four weeks after our final session together, the athlete reports no issues of any kind and is back to practice with her team without restriction.

I believe my approach is quite simple, straightforward, and not particularly groundbreaking. Good work need not always be revolutionary, though, right?

The athlete:

- Performed general athleticism-oriented lifting, including eccentric stress for the hamstring and core work targeted around pelvic control.

- Executed a linearly progressed sprint program.

- Made drastic improvements in her sprint technique.

- Was reminded of her success throughout the process.

Video 5. The weather prohibited us from sprinting over 20 meters during our final session, but this film from her third session shows clear improvements in her sprint technique. What’s more, the athlete’s fastest 10-meter split was slightly faster this day (session three) than on day one while sprinting with no pain, fear, or hesitation at 90% effort.

Personally, I think most of her hamstring performance improvement came as a result of the progressive sprint program and enhanced kinematics (although her trust and confidence in herself cannot be understated). The improvements she made in sprint technique put her in better positions not only to express force and sprint faster but also to protect her hamstring. Once that technique was achieved, she put it to use and progressively stressed her tissues with the sprint program.

Just as we wouldn’t push volume and intensity in a squat or deadlift for an athlete who can’t perform those lifts well—especially if those movements provoke symptoms—we should take the same approach with sprinting, especially with athletes who can’t sprint without experiencing symptoms!

Can every athlete achieve the same results this one did in just four weeks? Is it guaranteed she will never experience reinjury? Is every hamstring injury capable of healing in four weeks?

Certainly not.

But can every athlete improve sprint kinematics, address physical capacity with targeted strength and conditioning, and move the needle in the right direction?

Undoubtedly.

Can every athlete improve sprint kinematics, address physical capacity with targeted strength and conditioning, and move the needle in the right direction? Undoubtedly, says @KD_KyleDavey. Share on XWhile we cannot claim to eliminate the risk of injury—especially for hamstring pulls, which are notorious for becoming recurring issues—we can mitigate it.

For those looking to help athletes return to sport post-hamstring injury, or prevent injury in the first place, consider this basic yet effective approach.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Lahti J, Mendiguchia J, Ahtiainen J, et al. “Multifactorial individualised programme for hamstring muscle injury risk reduction in professional football: protocol for a prospective cohort study.” BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine. 2020;6(1):e000758.

Wulf G and Lewthwaite R. “Optimizing performance through intrinsic motivation and attention for learning: The OPTIMAL theory of motor learning.” Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 2016 Oct;23(5):1382–1414. doi: 10.3758/s13423-015-0999-9. PMID: 26833314.