James Mortimer has been coaching for over 10 years. During his tenure, he has coached athletes such as Zoe Hobbs, Portia Bing, and Liam Malone to international medals and global success. Before this, James competed at the Commonwealth Games and World Championships as a sprinter and at World Cups as a hurdler.

James has honed his skill set, learning from some of the best coaches in the world and gaining international recognition for his methods. He prides himself on coaching the athlete in front of him and delivering what they need without compromise.

Freelap USA: You’re about to go into coaching full-time, having previously worked in a school. What are some of the attributes that you developed throughout your teaching career that you feel cross over and assist you as a coach?

James Mortimer: You’re right; I have just left my position as a sports manager in a school in the last few weeks to run my coaching business full-time. My role at the school was largely to run a portfolio of different sports, and I think one of the biggest skills I developed in that role that serves me as a coach is the ability to manage large groups of people. Logistically, I have had to learn to ensure that, in large groups, everyone gets the attention they need to reach optimal progress.

I think, from one perspective, the most challenging coaching environment can be coaching kids. It’s very refreshing and helps you remember what the big rocks are—because the athletes are often a blank slate at this level. It not only helps to remind you which cues are effective but also to develop your ability to use those cues effectively. Part of my business is working with kids, and I think it’s helpful for me to stay in touch with that population for this reason.

When coaching kids or working in a school, it is really important to make sure it’s a fun experience for the learner; that is something I try to apply to my elite athletes as well, says @Morty_NZ. Share on XAdditionally, when coaching kids or working in a school, it is really important to make sure it’s a fun experience for the learner—and that is something I try to apply to my elite athletes as well. Training for athletics can be a fairly repetitive experience, so being creative and striving to make it fun can only serve to make training more positive, which has the potential to increase buy-in and athlete investment. I think an example of the impact of keeping the experiences fresh and fun is Zoe Hobbs’ indoor season in 2022.

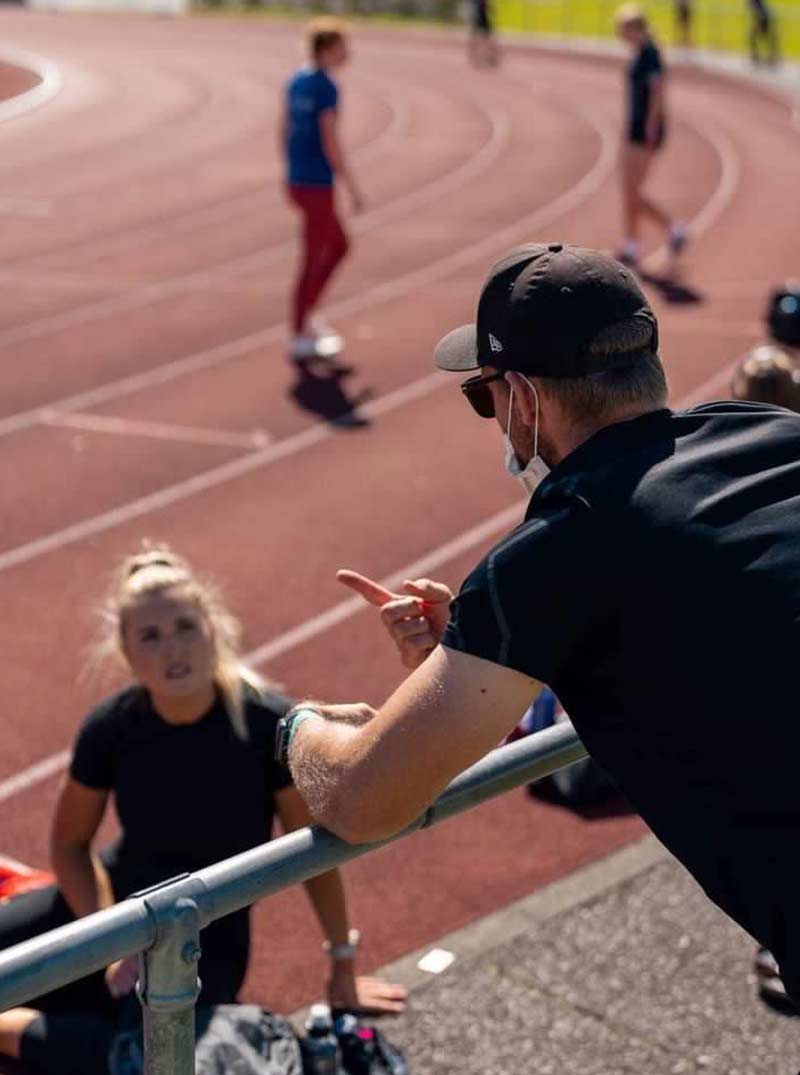

Photo courtesy of Seb Charles.

Zoe had never run an indoor competition prior to that year, and I think the freshness of the stimulus was engaging. She did one race in Europe before going to the World Indoor Championships in Serbia, where she took over a quarter of a second off the New Zealand record, running 7.13. She then ran 7.16 in the semifinals, missing the final by two 1/100ths of a second. I also think this showed Zoe that she really belonged on this stage, which reinforced her self-belief (a benefit in itself).

Freelap USA: Zoe Hobbs had a fantastic 2022. Were you expecting as much from her in 2022 as she delivered? What do you attribute her recent success to? Is it a challenge having her ready for the New Zealand domestic season and then the Northern Hemisphere’s season?

James Mortimer: I have been coaching for seven years, and she has been getting faster each of those years. I think the 2022 season was largely a product of consistent work over a prolonged period. I was surprised she ran as fast as she did so early. I wasn’t expecting her to run 11.09 at the Oceania Championships in Queensland in June in the rain with a small crowd, but it was obviously fantastic to see her do so well there and then go on to Eugene a month later and break the Oceania record again there.

There had been some training data that had suggested she increased her performance capacity, and interestingly, it didn’t only come from the stopwatch but also some gym and bike testing numbers. We’ve actually had it in the past where Zoe would hit new levels on bike testing one day and then go out the next day and run training PBs on the track. So while it’s not hugely specific, it’s nice to have another data point in addition to things like flying 30-meter runs, reinforcing that training is trending in a positive direction.

[vimeo 794696869 w=800]

Video 1. Zoe Hobbs Warm-up.

It’s disappointing that the World Indoor Championships in China will not be taking place this year, as Zoe and I both feel she could be even more competitive over 60 meters this season. Her start has always been a strong point for her, so I think she’s quite well-suited to the event. But luckily, she will be heading to the United States to run a couple of 60-meter races there before returning to New Zealand a couple of weeks before our national championships to complete our summer season here.

In response to the last part of the question, you can see that the Northern Hemisphere season coincides with our outdoor season—it’s a period when we would be running fast anyway, so there’s no need for us to periodize our training any differently, really. It’s more a case of it being a different event and in a different country!

It potentially gets a little more complicated with the Northern Hemisphere outdoor season, especially if the major championships take place relatively late. For example, in 2019, the World Championships in Doha finished in October—in those cases, by the time the athletes have had a period of rest and then some time to train, we may have to start our domestic season a bit later than we otherwise would.

It may be that the calendar faced by athletes from the Southern Hemisphere is reflected in our approach to training. I don’t think we really have time to do too much volume because we’re never far from a period where we need to race well; therefore, I tend to keep the intensity pretty high throughout the year.

I often wonder how I would approach training if I were coaching in Europe or North America, where athletes aren’t used to a double summer, says @Morty_NZ. Share on XI often wonder how I would approach training if I were coaching in Europe or North America, where athletes aren’t used to a double summer. Would it be a culture shock for them to have to work at the intensity I ask of my athletes in winter? I think it would feel strange to me to prescribe some higher volume sessions, as the way I do things is really all I’ve ever known through being an athlete and a coach in the Southern Hemisphere.

Freelap USA: Do you implement any resisted and/or assisted sprints in your programming? Is there any other sports technology that you have found to be particularly beneficial?

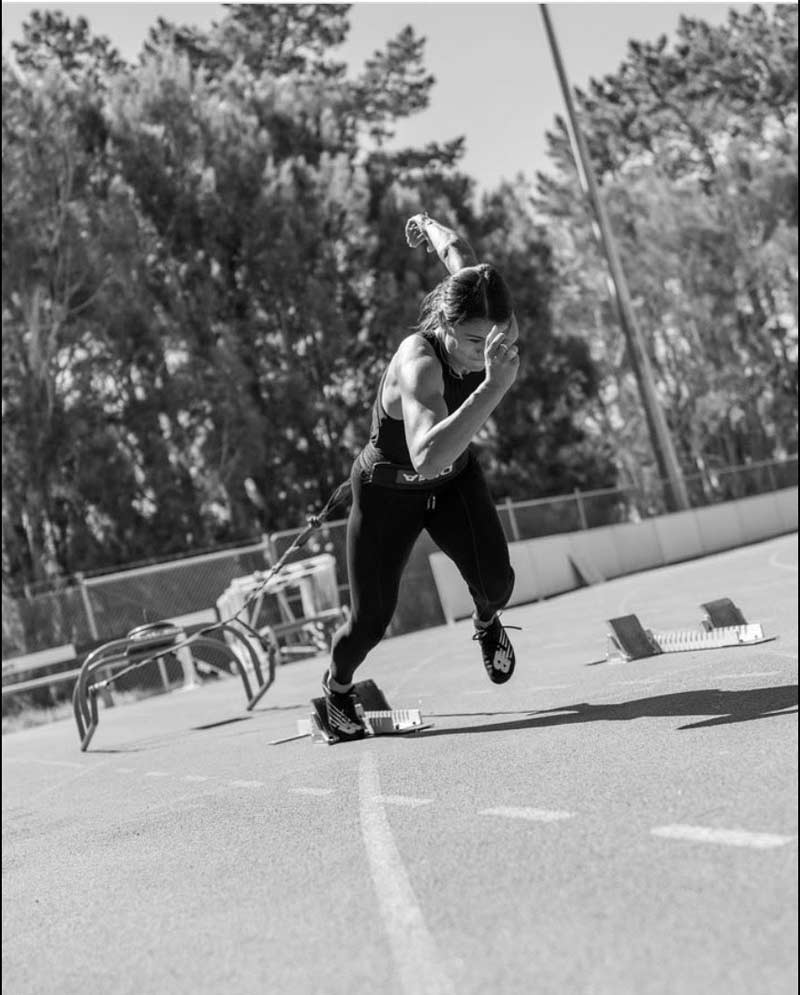

James Mortimer: I use both resisted and assisted sprinting in my program. We use resisted sprinting all year round for a couple of reasons. Firstly, I have my athletes do it as a learning opportunity to slow them down so they can work on technique and help them feel the correct angles through which they should be projecting. However, I also use it as a potentiation tool; for example, we may do one or two sled runs immediately prior to blocks, so they can maximize their intent when starting.

Photo courtesy of Seb Charles.

With assisted sprinting, I use a pulley system, so it’s literally a case of me “dragging” them along…but this is something I only use in the summer and only with a few athletes who I feel are ready to be exposed to work at this kind of intensity. For the athletes, an essential aspect of assisted sprinting is allowing themselves to be pulled along without fighting the assistance. An inexperienced athlete may not be able to handle this yet from a skill standpoint.

Additionally, I think it’s important to keep some tools in the toolbox and introduce them when perhaps progress has stalled. You hear of 12- or 13-year-old athletes who have been lifting heavy, doing overspeed, etc., and when they go to a new coach in the hope of running faster, a lot of training modalities have already been exhausted, limiting how much further improvement can be made.

On the track, I don’t have access to a lot of technology. The resisted sprints are performed with sleds, and as I said, the assisted sprinting is done with a pulley. But I use a Brower timing system, which, as I mentioned earlier, I may use for flying runs.

Freelap USA: What are some key technical landmarks you look for with your sprinters? Are there any cues in particular that you commonly use to hopefully help your athletes hit these positions?

James Mortimer: Ultimately, a lot of this comes down to the individual athlete, their interpretation of different cues, and how it impacts their execution of a skill. I almost need to have a thesaurus to find about six different ways to say the same thing so that I can communicate concepts to the different athletes in the language that best resonates with them. That said, I’m not trying to get all my athletes to look the same, as they will each have different positive attributes that make them fast, and I want them to be able to express those attributes when they sprint.

I don’t try to get all my athletes to look the same, as they will each have different positive attributes that make them fast, and I want them to be able to express those attributes when they sprint. Share on XI got into coaching around the time ALTIS was becoming more prominent, and they’ve been influential in my practice. So I use their kinogram model and look for things like the “figure 4” on stance. I’ve also found the kinogram particularly helpful in allowing me to communicate to my athletes some of the key positions I may be looking for; I can show them the sequence of positions and then potentially overlay the shapes they are making, so we can see where some potential differences may exist. Then, if we determine that a gap may be detrimental to their performance, we can target it.

I also explore some of Jonas Dodoo’s concepts, such as projection and switching, and see how the athlete responds before deciding on the best way to cue those movements for the individual athlete. One cue I find myself using a lot when coaching acceleration is “growing,” and I use this to refer to the change in posture from horizontal to vertical through the acceleration. I think telling them to grow expresses patience throughout the transition and promotes the idea of avoiding abrupt changes. I prefer this term to telling the athletes to “get tall” because the latter can lead to the athlete suddenly popping up.

Freelap USA: Are you able to outline a typical “pre-season” training week for your sprinters?

James Mortimer: Our training is affected by a lot of the constraints placed on us. For example, Tuesday nights are club nights at the track, so we’re limited with how much time we have to access the facility. That has become a session where we can get in and get out pretty quickly. Ideally, maybe the athletes would lift after the track session on a Tuesday, but at this point, they’re used to lifting first. They typically lift at around 7 a.m. before coming to the track at around 3 p.m., so there’s a pretty big gap that will give them some recovery.

On Saturday, we train in the morning so they can have the afternoon and Sunday as their own time. I think it’s important to consider what else the athletes have going on in their lives when planning the training week, as all the athletes work, including Zoe. By the same token, I think it’s essential to be flexible, and, providing the work for the week gets done, sometimes the order may need to be switched around a little bit—although I want them to come to the Thursday session having had Wednesday as a recovery day as much as possible.

-

Monday – Acceleration, which includes things like sleds, drills, horizontal projection-themed activities like standing long jump, and, in some cases, standing triple jump.

Tuesday – In the morning, the athletes will generally lift, and then in the evening, they will do an intensive tempo session, which is usually reps like 150s, 200s, 250s, and maybe a jump circuit.

Wednesday – Recovery day, which may include physio. Some may do something like yoga or Pilates, while others may go for a walk on the beach! I encourage this kind of activity to help them relax mentally as much as anything.

Thursday – Speed, as they have just had a recovery day, so they are pretty fresh, and we will do things like max v wickets.

Friday – The athletes lift again in the morning.

Saturday – I call this our “Go day,” which includes things like lactic tolerance, special endurance, and speed endurance. Zoe may have something like 80, 80, 70, 60 off good recovery, and the 400-meter athletes may have something like 100, 200, 300, 300, 200, 100.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF