For the better part of six years, despite never having intentions to do so, my work as an S&C coach has largely involved working with injured athletes. Discussing the role of a strength coach in an injury management or return to play (RTP) process plan can be murky at times, as injury restoration is not the focus of our credentialing. I believe S&C coaches often refrain from expanding their paradigm beyond bench, squat, sprint because we’re quick to be relegated to “our lane.”

While I fully understand and appreciate the constructs of our industry, I think this is fundamentally flawed. Reframing the contemporary perspective of strength coaches working with injured athletes is something I’ve become very passionate about. This starts with reframing the RTP paradigm, which we need to see as being more versatile and fluid since not everyone will have the same affordances. Although I will cover the majority of these points in this article, I recently spoke at length with my good friend and renowned physical therapist, Jimmy Rowland, about the topic—which you can find here.

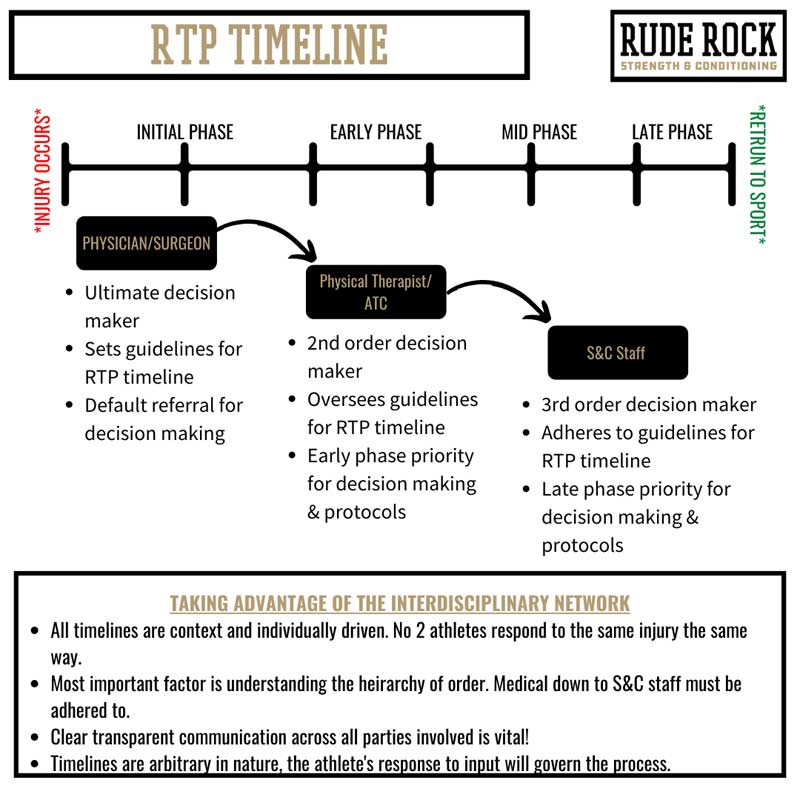

If we start by analyzing the optimal conditions, there is a clear hierarchical priority in the RTP process. In these instances, there is a top-down decision-making construct and responsibility to adhere to that is directed by the physician, facilitated by the physical therapist/ATC, and then transitioned back to the strength coach.

What often gets dismissed is the value that the strength coach can provide throughout the return-to-play timeline, particularly in the latter phases, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XAlthough nobody would dispute the significance of the medical staff, what often does get dismissed is the value that the strength coach can provide throughout the RTP timeline, particularly in the latter phases. While conventionally, S&C has been minimized in this process, largely due to our credentialing, my position is that we have undermined the versatility of strength training, and we should look to broaden our principles and perspective of the human body. Our level of effectiveness with athletes coming off of injury dictates that we reframe our view of training and how we can influence the body.

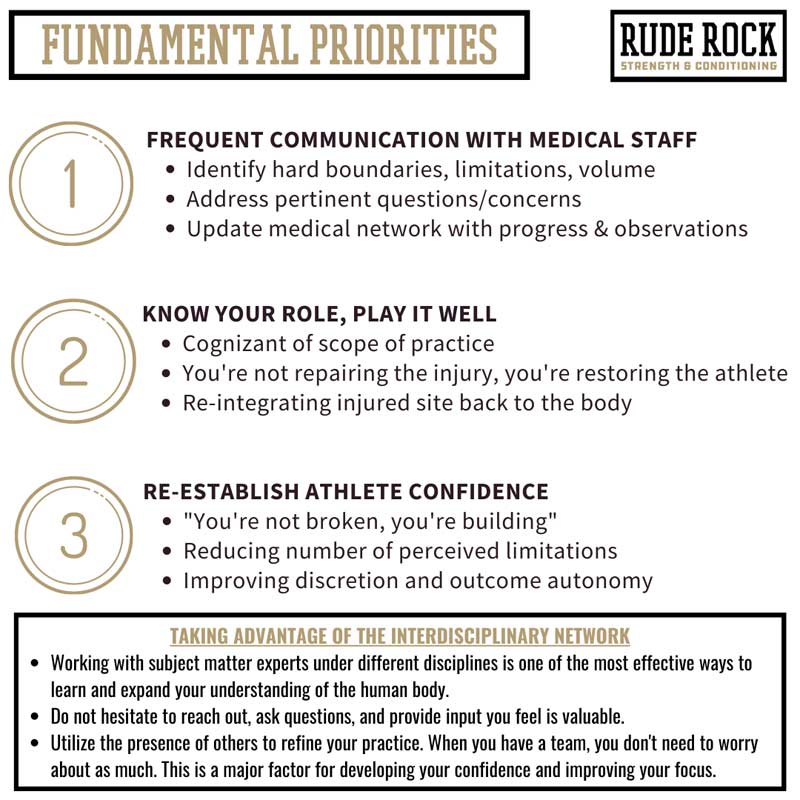

Strength coaches need to be prepared to accommodate all aspects of performance, which includes, considerably, the possibility of injuries. Fundamentally, the role of the strength coach is to adhere to the boundaries and guidelines provided by the physician or PT and work to become an extension of the medical staff in the training process. This includes having a thorough understanding of the mechanism of injury (MOI), what different types of treatment and modalities provide, and how coaches can modify their approach to best accommodate athletes returning from injury. All of this is missing from our academic upbringing.

Although working with injured athletes can be intimidating for strength coaches at first, over time, you will quickly recognize that not only does this not require you to do anything outside your scope, but there is a tremendous versatility to strength applications. In this article, I wanted to share the construct, mindset, and approach I’ve adopted for strength coaches working with injured athletes.

Base Priorities

As depicted in the graphic above, there is a specific role and place for each member of the human performance team when getting an athlete back to health. What is often misconstrued is that injury occurs in a binary manner, in which there are clear-cut, predictive delineations to both where an athlete should be and who should be responsible for what throughout the RTP timeline.

While these theoretical timelines help us develop a construct, it’s essential to recognize that the reality of the process is much messier than we want it to be. For instance, a common issue is that not many strength coaches have the luxury of an entire interdisciplinary team behind them. In these cases, more often than not, the default options implicitly become either do nothing or work around it.

This isn’t to be critical; rather, it justifies the demand for strength coaches to be better equipped and capable of working with injured athletes even more. But irrespective of your circumstances, it’s important to do the best with what you have. If you are working in tandem with a medical team, leave the early phase rehab to the experts. If you are in more of a dire position where you don’t have access to medical professionals, it’s imperative that you coordinate, at minimum, with the athlete’s physician and manage the remaining workload to the best of your ability.

Where the primary role of the PT/ATC is to specifically address the localized injury, our primary focus resides more on the global/integrative aspect of injury restoration. I see our value in restoring the composite athlete, not necessarily the specific injury. While this may seem like semantics, I believe the carryover is much broader when you examine the full spectrum of being an athlete. Amending the injury is obviously fundamental, but when athletes have extended time off due to injury, it isn’t just the area in question that becomes vulnerable—everything becomes vulnerable.

I see the S&C coach’s value in this as restoring the composite athlete, not necessarily the specific injury, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XA critical mistake I made early on was feeling that because an athlete had a specific injury, I had to dedicate 100% of my time and focus on “repairing the injury.” This was an example of me misconstruing my role and being shortsighted with what I would be able to provide. It’s important to recognize that, as an S&C coach, you are not responsible for the direct injury restoration: there are others on the performance team to address that. Conversely, the S&C coach can start to implement everything else (e.g., redeveloping upper-body strength after an ACL injury) in addition to the integrative aspects of the injured site.

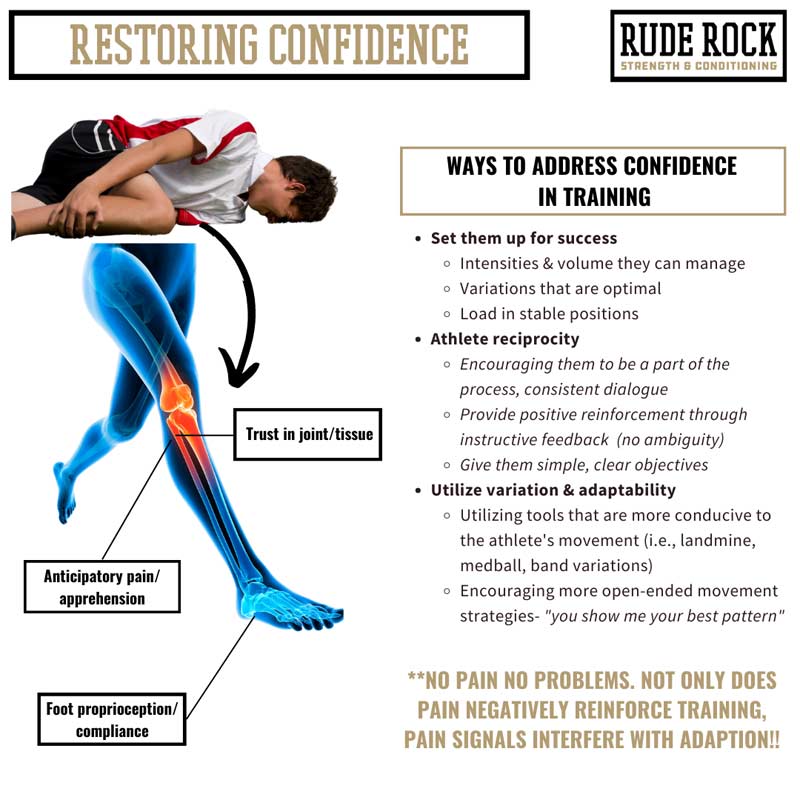

Building on this, restoring the athlete’s confidence can become a vital contribution from the S&C coach. I say this with the utmost respect, but physical therapy/ATC clinics can often (indirectly) be negative reinforcement for the athlete. Thinking about this from the athlete’s perspective: physical therapy instinctively screams “injured,” so the time with the PT/ATC can sometimes cloud the athlete’s confidence. When athletes suffer an injury (especially a severe or compound injury), it can be absolutely devastating to their confidence, trust in their body, and perception of their ability. Particularly with young athletes, injuries can be one of the first relatively traumatic experiences in their life, so the process of sustaining and recovering from an injury can be completely unknown to them.

Restoring the athlete’s confidence can also become a vital contribution from the S&C coach, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XI try to make it an exceptional priority to present an environment and dynamic that renders the athlete enthusiastic about training, and I back this by doing everything I can to set them up for success. It may seem trivial, but restoring confidence is a critical component and not always an easy task to achieve. Everything from our body language to our dialogue—and the training input itself—makes them feel confident and successful with what they are doing. And remember, without having a reference, clarity in outcome can be evasive.

Technical Priorities

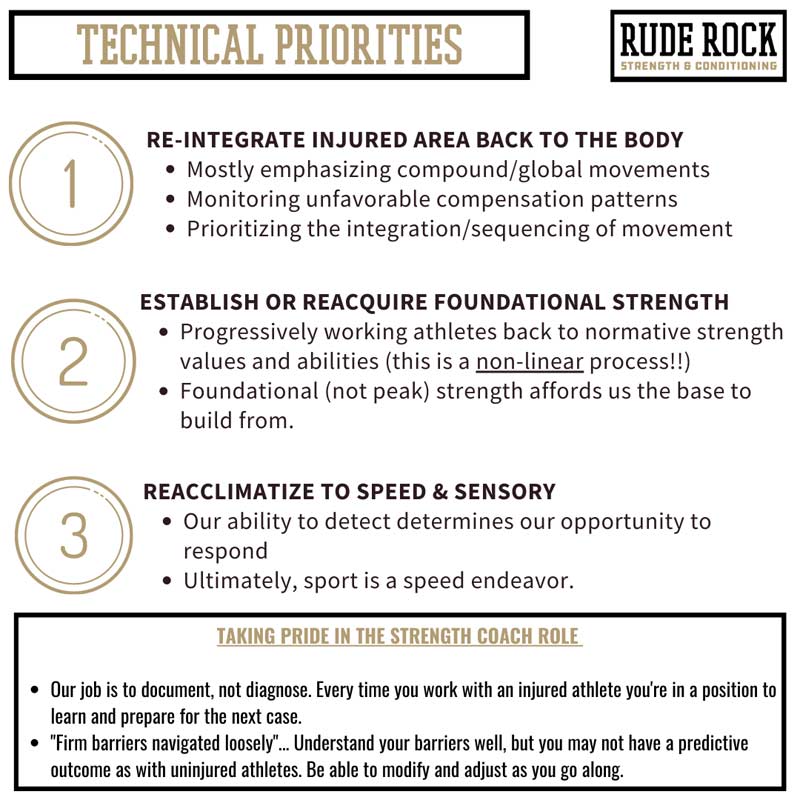

Injury restoration for strength coaches should be seen as an endeavor that demands critical thinking and problem-solving above anything else. Injuries often create situations and manifest in ways that deviate from what conventional practice suggests or what we would typically expect. The phrase I’ve adopted is “firm barriers navigated loosely,” or in other words, I know definitively what we can’t do, but let’s examine what we can do and how we can do it best.

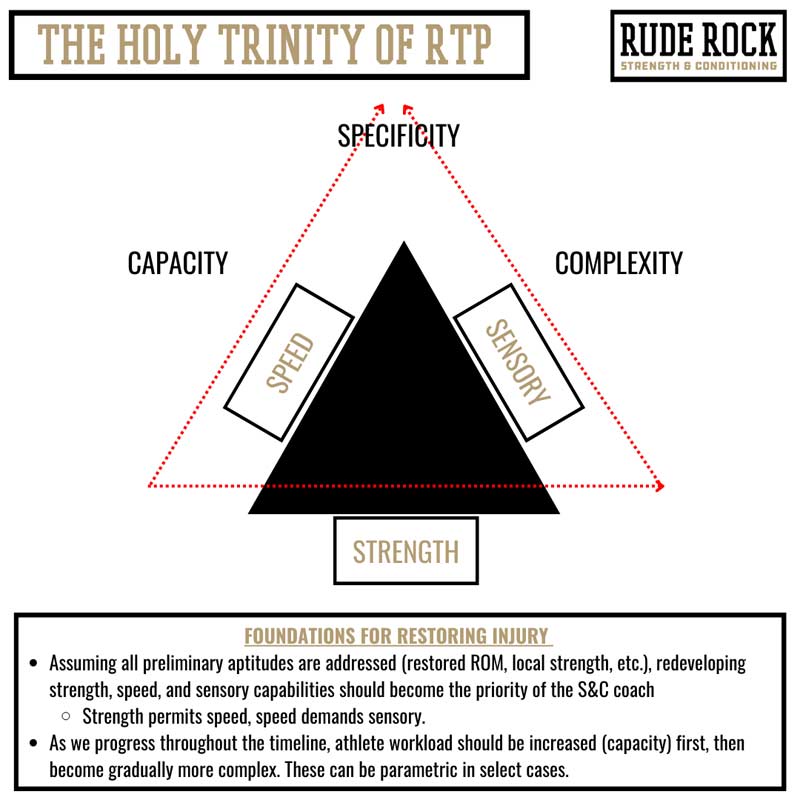

While developing the athlete’s confidence is our undercurrent, I summarize the technical priorities as:

- Reintegrating the injured area.

- Reacquiring foundational strength.

- Reacclimatizing to speed and sensory demands.

1.Reintegrating the Injured Area

This phase begins by picking up where the PT left off. As we’ve discussed, the PT and ATC are primarily focused on the localized injury, while the S&C component will be more of a global focus, with an emphasis on reintegrating the injured (local) site back into the body. There isn’t a clear-cut “playbook” for this process, but it doesn’t require anything beyond what we conventionally do—just certain things applied somewhat differently.

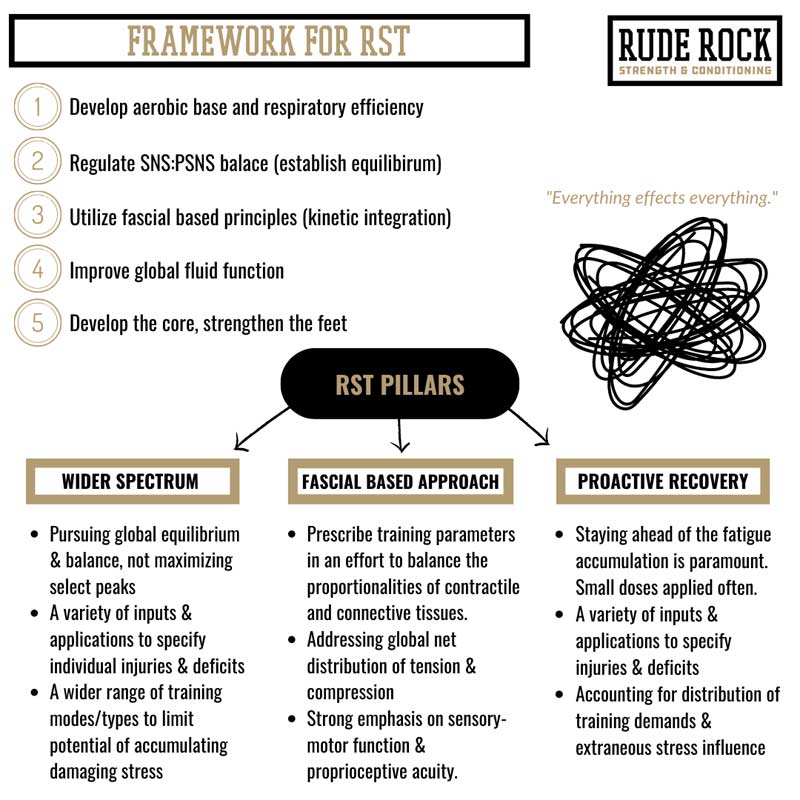

I’ve discussed this in previous articles, but the term I’ve come to use for these cases is “restorative-based strength training” (RST). To an extent, this has a GPP type of feel to it: start with a wide spectrum of input and parameters, increasingly work your way to a narrower focus (whatever it may be), utilize a good bit of rep and tempo ranges, and challenge multiple movements and vectors. However, it differs from a standard GPP block because it must also prioritize the area of interest.

2. Reacquiring Foundational Strength

This phase will be much more familiar for the S&C coach. Once we have addressed reintegrating the injured area, it’s time to load it. Unmistakably, applying force during the rehab and RTP process is fundamental, and it is a marquee component for the strength coach toward the later stages of the RTP timeline. The simplest way to analyze the importance of force is that we cannot comfortably have an athlete return to force exposures in an uncontrolled setting (game) without having experienced them in a controlled setting (training). Be reasonable and, at times, patient, but overall do not feel apprehensive about loading athletes or individuals coming off of injuries.

Another consideration for reacquiring strength after an injury is monitoring and managing the asymmetries. For almost any injury, especially extremity injuries, I prefer to work with a unilateral to bilateral progression scheme. The simple logic here is to independently strengthen the affected limb first before bilaterally challenging the athlete. This enables us to close the margins of non-functional asymmetries by not allowing the non-injured side to dominate, thus minimizing disproportionate effort between sides.

If we’re too quick to get athletes back under conventional bilateral lifts, we could put them in a vulnerable position to reinforce differences in limb strength, or nonfunctional asymmetry. Share on XI follow the principles Matt Jordan provides, where we want to see no more than a 5% difference between limbs across functional strength and other standard measures. Additionally, I believe it’s important to establish ~90% of unilateral strength (pre-injury) for major movements before we look to load bilateral movements heavy (~80%) or implement any high-velocity or speed work. If we’re too quick to get athletes back under conventional, bilateral lifts, we could put them in a vulnerable position to reinforce differences in limb strength, or non-functional asymmetry (>10% difference). The added benefit of the unilateral emphasis is that it also addresses unwanted compensatory patterns that have likely developed throughout the injury process.

3. Reacclimatizing to Speed and Sensory Demands

Ultimately, sport is a speed endeavor. And my theory is that if they’re exposed to it in sport, we need to experience it in training. Similar to high-force applications, coaches can be apprehensive about applying higher velocities and dynamic movements with athletes coming off an injury. But again, the reality is that we can’t adequately restore the injury without addressing the speed and dynamic components.

A priority in this phase is attuning the proprioceptive, neural, and fascial functions. Consider these as our collective sensory and connection systems; each plays an inextricable role in injuries. With this, we need to consider the sensitivity and responsiveness of the area. I look at it as the ability to detect and then create the opportunity to respond. With almost any injury mechanism, particularly soft tissue or chronic overuse, it typically isn’t the amount of force that causes injury but the rate at which it’s applied.

This is when we should start to implement standard sprint, acceleration, and plyo movements back into programming but do so in submaximal intensities. Generally speaking, I work from within a 60%–80% range and look for various other ways to progress the movement or drill. A few simple ways to build in progression outside of more load or volume include:

- Increasing joint angles.

- Changing load type or placement.

- Increasing time under tension.

- Utilizing multiple directions.

- Increasing complexity.

- Changing surface type.

- Adding a reactive element.

And to touch on volume, be sure to progress the workload more cautiously than the intensity. As discussed, responses to injury and the restorative process are highly individualized. Learn how athletes respond to stress before cranking up the volume and ground contacts. There can be somewhat of a delayed effect with soft tissue injuries, so a two-day window should be monitored.

In the speed phase, two things are omnipresent:

- The chance of setback/injury.

- The athlete having great difficulties with trust/confidence.

As I mentioned above, injuries are a byproduct of speed, more so than force. When we’re reintroducing an athlete to speed—even submaximally—it is critical that we monitor them closely. A trap people fall into is fearing the early and mid-phases of RTP, thinking that because the athlete is more physically delicate during this window, they are more inclined to injury. The truth is, at least in my experience, the later phases are where things can really hit a snag. A consideration here is that acute pain levels have generally diminished by this phase of RTP, so the athlete is more confident and aggressive with training.

But all of this is to say, first, pain is in no way a determinant of function; just because we don’t have pain, it doesn’t mean we’re in the clear. Athletes can also become antsy by this point, assuming that because a certain amount of time has passed, they “should be able to do ___” (fill in the blank). Tempering their expectations and anxiousness is fundamental to preserving their well-being; continue to do your best to keep them focused on the present.

Something I’ve found highly successful for this phase of RTP is utilizing a lot of video review. Apart from providing both the coach and the athlete with several points to examine in detail, video also gives the athlete a very objective view of where they are in their RTP process. Doing it this way allows the athlete to see themselves and focus more on instructive feedback than on what they’re “not doing” or perhaps what doesn’t feel great.

This is a subtle way to repair confidence because it creates an “identify and correct” pattern. The athlete identifies the fault, corrects it, and subsequently feels rewarded by tangible and visual improvement. Everyone wins.

Discussion

The role of the strength coach is integral to a successful outcome for injured athletes, and although that role can be lost or diminished within the hierarchical RTP framework, we need to recognize that injury is not binary. As such, while our role may not be at the forefront in earlier phases of the rehab process, it will become increasingly significant as the athlete continues to approach returning to health. When conducted optimally, there is a fluid tandem and tradeoff of emphasis throughout the interdisciplinary team and the timeline.

I believe it is a fundamental priority for all strength coaches to become better versed in injury mechanisms and restoration, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XInjuries are an inextricable reality of sports, and no matter how sophisticated or advanced our tracking tools, resources, and applications get, athletes will always be susceptible to injury. Rather than being trapped in dogmatic beliefs that confine our ability to make an impact, I believe it is a fundamental priority for all strength coaches to become better versed in injury mechanisms and restoration. The better we can understand and amend injuries, the broader our value becomes. This does not require you to breach the scope of practice; it just demands that you examine the versatility of your craft and get better at modifying and adapting what you do to fit an injured population. This is an endeavor to immerse yourself in, not fear.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF