“Do you lift weights to get strong, or do you get strong to lift weights?

That is the question strength coaches should ask when deciding whether or not to include high pulls in their program. Another way to phrase it is, “Am I using high pulls to help my athletes get better at the clean, or am I using high pulls in place of the clean?”

To ensure we’re on the same page, a high pull begins with the barbell on the floor, as with a clean or power clean. You stand up quickly, fully extend your legs, rise on the balls of your feet as you shrug your shoulders, and follow through with your arms. Done! You don’t turn over your wrists and catch the weight—just let it drop. Oh, and weightlifters call these exercises pulls, not high pulls.

Many strength coaches have their athletes perform pulls rather than the snatch, the clean, or their power versions. Sometimes, it’s not by choice—often, these coaches don’t know how to teach the full lifts, don’t have enough staff to teach them (at Brown, a handful of coaches work with 1,200 athletes in 36 varsity and 12 club sports!), or don’t have the facilities and equipment (good barbells, bumper plates, platforms) to perform them safely.

Beyond those formidable challenges, there are many other reasons strength coaches have their athletes perform pulls.

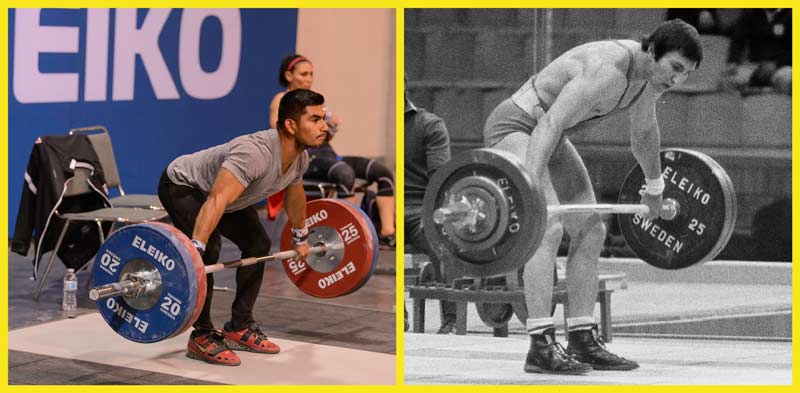

Lead Photo by Vivian Podhaiski, LiftingLife.com photos

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=11155]

The Case for Pulls

This discussion relates to coaching for non-weightlifters. That is, using the Olympic lifts or their components to improve sports performance. I’ll explain why this distinction is essential in the final section.

What attracts many sprint coaches to pulls is that they improve explosiveness. More specifically, the ability to initiate force (such as with a sprint start) and apply force into the ground (to increase stride length).

What attracts many sprint coaches to pulls is that they improve explosiveness. More specifically, the ability to initiate force and apply force into the ground. Share on X

With that background, here are 11 reasons why many strength coaches and sports coaches like pulls:

1. Helps Teach the Olympic Lifts

The Olympic lifts are complex movements. Many coaches believe it’s best to break down the lifts into parts when working with beginners. To teach the power clean, a coach may start by having their athletes perform a pull from the mid-thigh, then with the bar at knee height, and finally from the floor. When the pull from the floor is mastered, they add the catch to complete a power clean or descend into a full squat to perform a full clean.

2. Strengthens the Posterior Chain

If you want to excel in weightlifting exercises, you have to be strong from the start. Flexing the spine as you separate the bar from the platform is harsh on the lower back. Also, lifting your hips too soon due to relative weakness in the posterior chain muscles is inefficient, causing the bar to slow down and often to drift forward, away from an optimal movement pattern.

Pulls target the initial lift off the floor, strengthening the lower back, hamstrings, and glutes. For athletes especially weak off the floor, coaches might prescribe a form of “stutter reps,” which involve pausing at a specific point(s) of a lift. For example, the athlete would pull the bar to just below the knees, pause for 2–3 seconds, then complete the pull. (Yes, a Romanian deadlift will work these muscles, but it’s not mechanically specific to the pull in weightlifting and has limited value since it’s a partial-range exercise.)

3. Strengthens the Neck and Traps

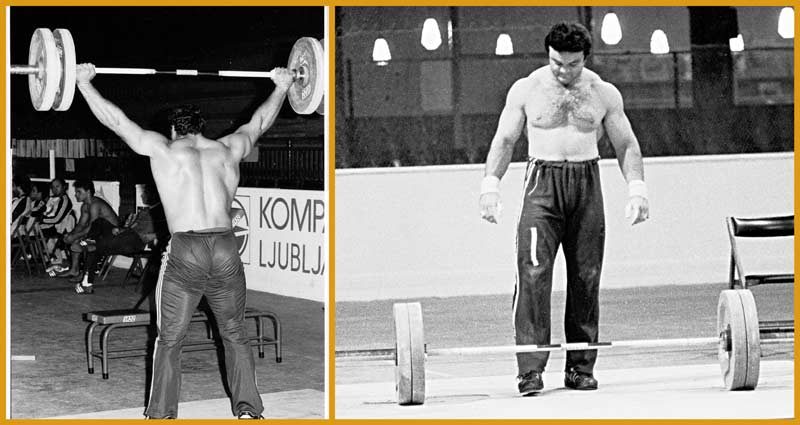

Pulls strengthen the trapezius (the diamond-shaped muscle on the upper back) and the neck, significantly reducing the risk of concussions. Because the training of weightlifters is focused on developing relative strength (except for the super heavyweights), it’s often difficult to distinguish weightlifters from other athletes just by looking at them. The exception would be the neck and trapezius, which are usually well-developed.

It’s often difficult to distinguish weightlifters from other athletes just by looking at them. The exception would be the neck and trapezius, which are usually well-developed. Share on X

4. Places Minimal Stress on Wrists

Many sports coaches are afraid of having their athletes catch cleans or snatches. They have reason for concern. If a golfer or baseball player injures their wrists, competing in or even practicing their sport may not be possible. So, “no” to cleans and snatches, but “yes” to so-called “functional” rubber band exercises.

After five decades in the sport, I can say this fear of injury is unfounded…that is, if the coach knows how to teach the lifts and quality equipment is available. (This is one of my pet peeves. Many strength coaches will spend tens of thousands of dollars for resistance-training machines that isolate a single muscle but will only purchase cheap barbells of the quality you would find at a discount department store.)

After five decades in the sport, I can say this fear of injury is unfounded…that is, if the coach knows how to teach the lifts, and quality equipment is available. Share on X5. Motivates Athletes

Many athletes don’t like being in the weight room and quickly get bored, despite being allowed to blast their soulless music. (Seriously, haven’t any of these young people heard of Boz Scaggs or that band Paul McCartney was in before Wings?) Adding pulls provides variety to a workout that makes the weight room more tolerable for non-weightlifters.

Adding pulls increases the number of personal records athletes can make because they will be performing more exercises. Setting personal records is important in training youth—they want a payoff with personal records as often as possible. One reason for the popularity of the Bigger Faster Stronger workout program in high schools for nearly five decades is that it’s designed with enough variety that athletes can easily break a dozen personal records every week.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=11142]

6. Increases Repetition Pool

Canadian strength coach Charles R. Poliquin believed that the repetition was the foundation of any strength training program. He said the other loading parameters, including sets and rest periods, were influenced by how many reps should be performed.

With the Olympic lifts and the power versions, the number of reps that can be performed with optimal technique is much lower than pulls—weightlifters often joke that anything more than two reps in a weightlifting exercise is considered cardio! Whereas performing three reps or more in a snatch or clean is a challenge that dramatically reduces the amount of weight lifted, pulls can be performed for much higher reps with heavy weights to develop other strength qualities, including hypertrophy.

7. Increases Training Volume

Pulls involve a lot of muscle mass, so they take the place of several exercises. Rather than performing a deadlift, upright row, shoulder shrug, and calf raise, just do pulls. Pulls also require fewer warm-up sets than the full variations of the lifts because they are less complex. If pressed for time, pulls are an excellent alternative.

Pulls involve a lot of muscle mass, so they take the place of several exercises. Rather than performing a deadlift, upright row, shoulder shrug, and calf raise, just do pulls. Share on XMy weightlifting coach was Jim Schmitz, a three-time coach for the U.S. Olympic team. He coached the first American to Olympic press 500 pounds, the first to snatch 400, and the first to clean and jerk 500. All his athletes trained only three times a week for about 90–120 minutes. That’s it! Just my opinion, but I believe the pulls Schmitz included in his program significantly increased the training volume to produce positive hormonal adaptations that stimulated strength gains.

8. Enhances the Quality of In-Season Training

Time is a luxury that athletes don’t have during a season. With games scheduled every week, sports coaches may only allow their athletes to be in the weight room for 30 minutes twice a week. However, with some sports, the athletes are so beat up after a game that it may be a struggle to perform the full Olympic lifts. After a game, football players and others in contact sports are often so beat up that they have little interest in catching a barbell on their shoulders or even lifting their arms overhead.

These athletes could perform higher-repetition pulls while they heal. These exercises will maintain (or even increase) their pulling strength so they can quickly get back into full or power versions of the Olympic lifts. Pulls will also give their coaches an indication of their conditioning, according to one recent research paper.

That paper, a German study published in 2021, examined the association between snatch pulls and one-repetition maxes in snatches. Ignoring the Sheldon Cooper Big Bang Theory notations, the researchers said their study “provides a new approach to estimate 1RM snatch performance in elite weightlifters using the snatch pull FvR2.” Most importantly, “The results demonstrate that the snatchth-model accurately predicts 1RM snatch performance.”

9. Ramps Up Detrained Athletes

Deconditioning is a problem with high school and college athletes. They have long breaks during the summer (three months) and winter (one month), and injured athletes often are away from the weight room. These athletes can ease into heavy training with pulls during the initial training sessions and get their form back for the explosive lifts.

10. Matches an Athlete’s Strength Curve

Strength coaches use chains and bands to alter the resistance curves of exercises to match an athlete’s strength curve. With pulls, the barbell reacts to an athlete’s increased force production by accelerating. (FYI: Performing pulls with bands is a bad idea since the tension increases dramatically at the top of the lift, increasing the risk of the athlete losing their grip and possibly injuring themself.)

11. Works Around Injuries

Many injuries will prevent athletes from performing power cleans, power snatches, or the full lifts. However, because there is no catch and the pulls can be performed from various heights, injured athletes can often perform pulls to maintain or even increase their strength. This advantage applies to upper-body and lower-body injuries. Consider knee injuries such as tendinitis.

As the athlete receives treatment for this condition, they might be able to perform pulls—just releasing the bar at the top (as long as you use bumpers). What about the power variations of the lifts? They’re generally not a good idea. A power clean or power snatch ends with a catch position that puts a large amount of stress on the knees, especially the ACL. Further, it’s not a quarter squat where an athlete eases into the position, but a rapidly moving barbell they must catch with an abrupt stop.

The Pull Experience

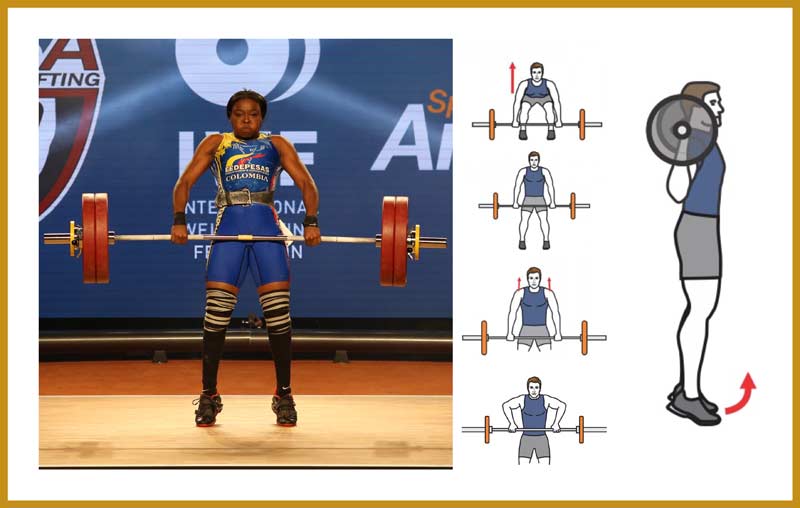

Most athletes will only perform the clean pull, the first component of a power clean or full clean. Let’s look at a few other variations.

The two basic types of pulls are clean pulls and snatch pulls. The difference between the clean pull and a snatch pull is that the snatch pull uses a wider grip, the same grip you would use if performing a power snatch or full snatch.

Pulls can be broken down further, including those from the knee and mid-thigh. The athlete can take the barbell from the ground to a deadlift position and lower the bar to where they want to start, take the barbell off power rack supports and lower the bar into position, or perform them from blocks. Performing pulls from blocks gives athletes more time to ensure they are in the optimal pulling position. On the other end of the pulling spectrum are pulls performed standing on a low platform (bumper plates are often used), increasing the work of the quads at the start; these are usually called pulls from a deficit.

One problem with partial-range pulls is that athletes tend to extend their shoulders too far over the bar and heave it into a large arc. Not only is this technique mechanically different from the Olympic lifts, but it creates a much slower movement that (to quote Coach Poliquin) “can be timed with a calendar!”

Other variations of pulls include East German pulls and flat-footed pulls. With flat-footed pulls, the idea is not to come up on your heels to increase the work of the upper body—even lifting your toes and pushing your heels into the floor at the finish to keep you grounded. As for East German pulls, I first learned about them in the ’70s, but they have become so popular with Chinese lifters that most lifters refer to them as Panda pulls. The difference is that the lifter drops down at the top of the pull so that the bar is level with the throat. The idea is to better simulate the movement under the bar during a full lift.

Why is this important? At the top of a pull, the quadriceps relax. In contrast, when a weightlifter moves under the bar during a full lift, there is still some tension in these muscles. According to weightlifting sports scientist Andrew “Bud” Charniga, this tension protects the knee joint in the bottom position. “When you extend too long in the snatch or a clean, the quadriceps relax at the top of the movement. When you drop into the bottom position, there is not enough time for these muscles to significantly contract again to protect your knees. In my experience, this is one reason you see a lot more U.S. lifters wearing knee wraps, at least compared to the Europeans.”

The idea of the East German pull is to maintain that slight overlap of the quadriceps (agonist muscles contracting to extend the knee) and hamstrings (antagonist muscles to flex the knee). Two takeaways are to keep the volume of pulls low to avoid reinforcing an inferior movement pattern and perform them after the full weightlifting movements.

Consider that when you shorten the range of motion, you also reduce the time the muscles are under tension. If your goal is muscular hypertrophy, particularly in the trapezius, you’ll need to perform higher repetitions when performing a pull from the mid-thigh or knee level. Using several of the variations discussed, here is how you could adjust the sets and reps to produce the same amount of time under tension:

-

Clean pull from deficit, 5 x 2

Clean pull from floor, 5 x 3

Clean pull from knee, 4 x 4

Clean pull from mid-thigh, 3 x 5

One issue with partial pulls is that you reduce the contribution of other muscles to power. For example, at the start of the pull, the soleus (lower calf muscle) helps to pull the shin back, thus assisting the quadriceps in straightening the knee. Notes Charniga, “Contraction of soleus pulls the shin backward, assisting the straightening of the knee and even hip, because shin bones are interconnected to thigh bones and hip by means of the knee joint. Consequently, when this muscle straightens the shin, thigh and hip are accelerated into extension; because, ankle, thigh and hip are interconnected by couplings.”

Yes, an athlete can place the bar in the crease of their hips and kick up a considerable amount of weight, but that doesn’t mean their muscles are producing massive amounts of power. Which reminds me of a funny story.

In my early coaching years, I trained in a gym with various Iron Game athletes. One day I was working with a talented 14-year-old female weightlifter who could clean and jerk 154 pounds at a bodyweight of 120. Her superpower was that she had leverages (short back/long arms) that made her remarkably good at shoulder shrugs.

At the end of one workout, two bodybuilders (wearing colorful do-rags and clown pants) were showing off doing mid-thigh shoulder shrugs with 315 pounds, taking the bar off of blocks. After each set, they celebrated as if they had just won the Olympics. My athlete had enough of their tomfoolery—she walked over to where they were training and asked them if she could jump in for a set. They grinned, said, “sure!” and sat back and waited for the accident to happen. Instead, she added 10 pounds to each side and cranked out 10 reps. My career as a coach was complete!

Getting back on point, another challenge with pulls is that athletes tend to lift with less intent than with a full or power version of the snatch or clean because there is no catch. A velocity-based training unit can provide immediate feedback to motivate the lifter to pull harder. At Coach Schmitz’s gym, we had access to an adjustable crane-shaped post with a piece of metal dangling from the top of it. During a pull, the end of the barbell would tap the tin to provide us with feedback about the bar’s pulling height. However, a VBT unit can give the athlete immediate feedback on how much effort they put into each rep.

Now we come to a significant point of controversy in weightlifting: Many coaches see limited value in pulls, and some see no value in them whatsoever.

The Pull Problem

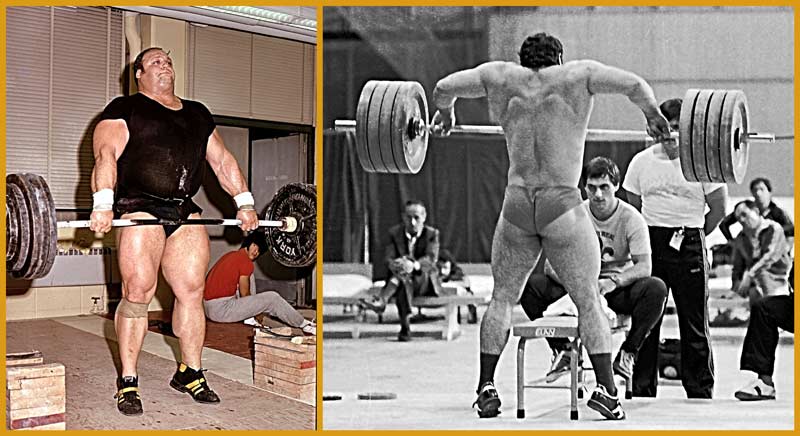

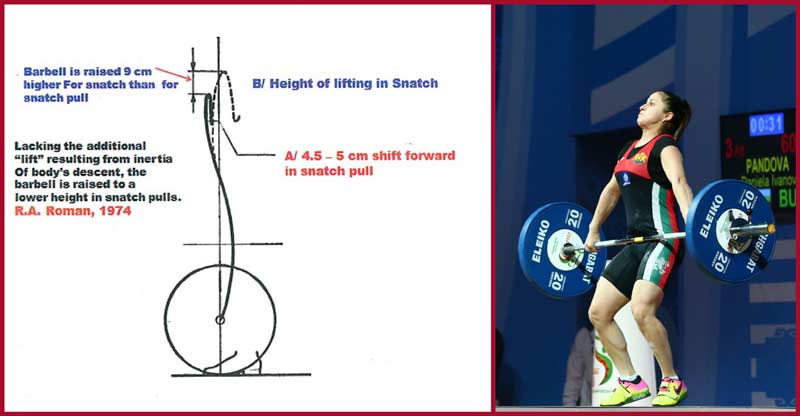

In 1977, a paper was published by three notable weightlifting scientists called “The Training Weights in the Snatch Pull.” The researchers said that weights over 110% had “a different rhythm than in the snatch.” More specifically, the mechanics of a pull are different than what occurs in a full lift and can thus create a negative transfer to weightlifting performance.

One difference is that the ankles will not flex as much (causing the heels to rise) with pulls, reducing the contribution of the elastic properties of the connective tissues, thus reducing power. Also, because the athlete is not moving under the bar, the bar tends to shift forward at the top, away from the body’s center of mass (COM), where maximum power can be produced.

To work around this issue, the researchers recommended to “strictly control the number of lifts with weights over 90% of the maximum snatch, especially in the competition periods.” In his classic 1974 textbook, The Training of the Weightlifter, sports scientist Robert A. Roman said super-maximal weights (above 100%) could be performed if they were partial pulls, such as from the mid-thigh.

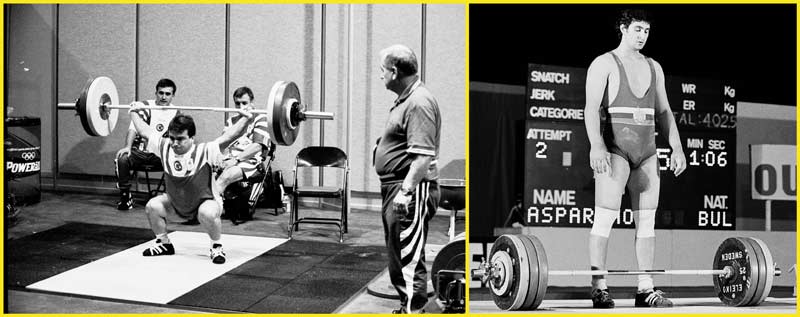

In the “no value whatsoever” corner was Ivan Abadjiev, the former head coach of the Bulgarian National Weightlifting Team. Under Abadjiev’s direction, Bulgarians won Olympic gold 12 times and 54 World Championships. These results are remarkable because the Bulgarians had a small athletic budget, and their talent pool was limited to a population of fewer than seven million people.

Abadjiev believed that pulls were worthless for his elite weightlifters, and the best way to make weightlifters stronger for the lifts was to perform more lifts. (Again, “lift weights to get strong.”) This sport-specific approach necessitated using relatively low rep sets to focus only on the fastest muscle fibers and avoid developing excessive muscle mass. How many sets?

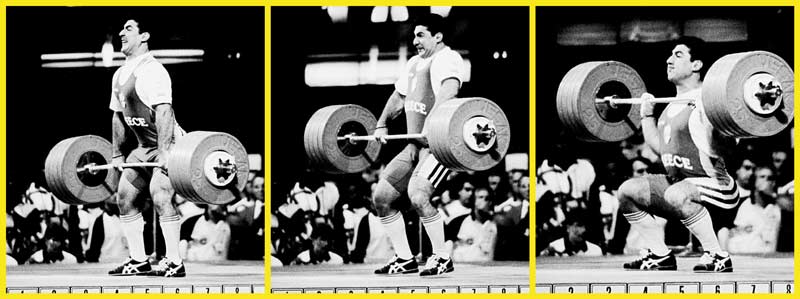

Consider that Abadjiev would have his lifter train five times a day, 5–6 days a week. Snatches, clean and jerks, and squats—that’s pretty much it! After he won his third Olympic gold in 1988, I interviewed Abadjiev’s greatest student, Naim “The Pocket Hercules” Süleymanoğlu. He told me he no longer did back squats because they were “not specific.” At 132 pounds bodyweight, Süleymanoğlu established himself as the greatest pound-for-pound weightlifter in history by snatching 336 pounds and clean and jerking 418. Success leaves clues!

When Abadjiev visited our gym a dozen years ago, I had the opportunity to interview him and watch him coach one of his athletes. Besides dispelling the nonsense that his elite athletes were performing so-called “Bulgarian split squats” and step-ups, he told me he had dropped back squats from his program, only performing front squats. And pulls? Don’t be silly!

One issue with pulls is that the lifter uses their arms to lift the bar higher rather than pull their body under, thus reducing power production. Share on XOne issue with pulls is that the lifter uses their arms to lift the bar higher rather than pull their body under, thus reducing power production. With the full lifts, as the lifter pulls themselves under the bar, the barbell will continue its upward trajectory because the lifter actively applies force to the bar with their arms, even if their feet are not in contact with the floor. Further, sequence photos of weightlifters show that the athlete’s feet do not have to be in contact with the floor to apply force onto the bar—thus, at least in weightlifting, you can “fire a cannon out of a canoe.”

An issue with pulls that finish with an arm bend is that they require the bar to move ahead of the body’s center of mass, whereas the optimal technique keeps the bar more in line with the COM. For this reason, many coaches do not have their lifters follow through with the arms.

Video 1. A video showing the progression of the pulling technique of Christian, one of the author’s athletes. It begins with a screen capture from before working with the author, where he starts pulling the bar straight up rather than toward his center of mass. His first training session follows it, then two lifts from one of his early meets. Eventually, Christian broke the New England record in the snatch and the clean and jerk.

The dominant Chinese lifters indeed do pulls. The argument is that their training volume in pulls is relatively small and will not adversely affect their technique—just like a professional tennis player won’t lose their serve if they play an occasional game of racquetball. Also, consider that in a country of more than 1.4 billion people, their talent pool is such that they have the luxury of making mistakes.

The jury is still out on pulls for weightlifters, as there are Olympic champions and world record holders who have used them and those who have not. It appears that advanced lifters who perform a high volume of Olympic lifts could do pulls with submaximal weights or partial pulls with super-maximal weights without adversely affecting their technique. If training time is limited, it’s probably best to avoid pulls and focus on the full movements.

Should you include pulls in your program? While the jury is still out for weightlifters, there are pros for other athletes. Consider the arguments presented here and make the best decision for you and your athletes.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Charniga, Andrew, Jr., A Demasculinization of Strength, June 8, 2020: pp 65–70. www.sportivnypress.com

Charniga, Andrew, Jr., “The Foot, the Ankle Joint and An Asian Pull.” January 21, 2016. www.sportivnypress.com

Charniga, Andrew, Jr., Personal communication. February 2008.

Frolov VI, Efimov NM, and Vanagas MP. “The Training Weights in the Snatch Pull.” Tyazhelaya Atletika, Fizkultura I Sport Publishers, Moscow, 1977:65–67. Translated by Andrew Charniga www.sportivnypress.com

Roman, Robert A., “The Training of the Weightlifter in the Biathlon,” Moscow, FIS, 1974. Translated by Andrew Charniga, Jr.

Roman, Robert A., 1974 Weightlifting Yearbook. Translated by Andrew Charniga.

Sandau I, Chaabene H, and Granacher U. “Predictive Validity of the Snatch Pull Force-Velocity Profile to Determine the Snatch One Repetition-Maximum in Male and Female Elite Weightlifters.” Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2021;6:35.