The name of the game for GPS use is efficiency. It all boils down to how I, as a performance coach, use this tool to the fullest extent to monitor athletes and make load-prescription recommendations to our sport coaches based on the demands of their game and their style of play. I serve over 250 athletes and eight varsity sports that use our GPS system, but there is only one of me. All the data in the world is meaningless unless I have a streamlined approach to get the data that matters to our sports coaches.

So, how do I establish routines and practices that make our systems more efficient? The truth is that the proper provider is better than any system I can develop on my end.

In the selection process, one primary question must be answered: Which provider gives an accurate, holistic view of what athletes are going through without requiring an immense amount of data filtering and sorting? A lack of efficiency in data management can cause a tremendous amount of data, resulting in users becoming overwhelmed and implementing only a fraction of the potential benefits of their GPS system.

A lack of efficiency in data management can lead to a huge amount of data, resulting in users becoming overwhelmed and implementing only a fraction of the GPS system’s potential benefits. Share on XIn this article, I will discuss essential considerations and give my experience with entry-level units from both Catapult and Titan Sports. This article is not meant to endorse either product but rather to provide insight into the use of both products. Users should consider the constraints and goals of the program to determine which is right for them.

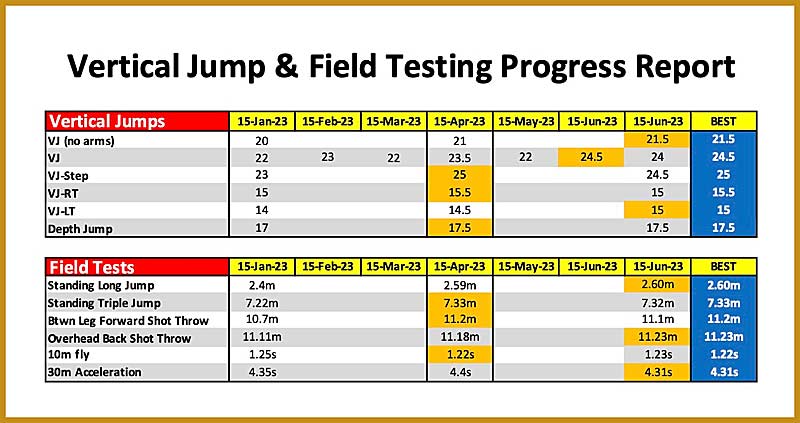

Considerations Within Data Management: Tracking Progress

The first question to ask is: How does this system track athlete progress over time?

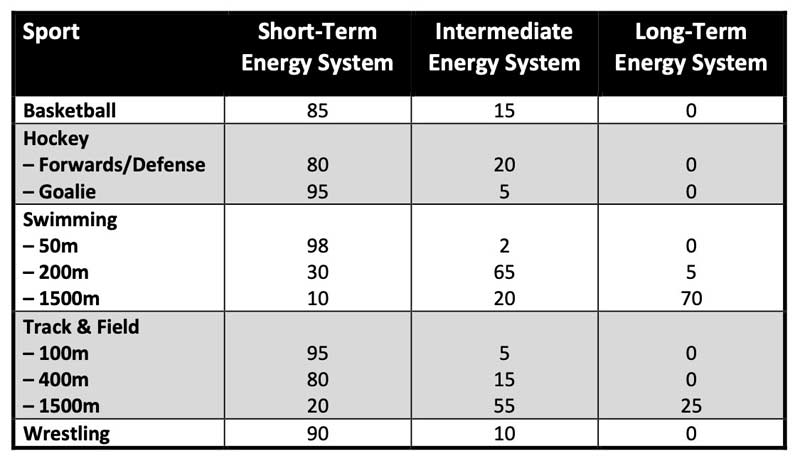

This foundational question must be answered using metrics that each system tracks. All systems track variations to top speed, high speed/sprint yardage, acceleration/deceleration, and a GPS load. These metrics form what I term “Level 1 metrics,” or the metrics that I teach our sport coaches how to interpret. Where providers begin to separate themselves is access to more detailed metrics, which I term “Level 2.” These include acute:chronic work ratio (ACWR), accel/decel band counts, and video analysis.

Strictly comparing entry-level units—as this is the budgetary framework many high schools typically fall into—Titan offers a holistic view on the home screen. With Titan, every Level 1 and Level 2 metric, in addition to others, is found on the home screen. Catapult offers Level 1 metrics from their home screen, but ACWR and video analysis are not offered. Accel/decel counts, among other metrics, are available through CSV export.

Having this data at your fingertips with no sorting is essential for efficiency. However, the ability to compare collected data over time is a must. If I cannot establish how each athlete’s session compares to team and individual averages over a given period, I fail to identify necessary trends in practice volumes and intensities.

I found Titan’s ability to view athlete progress over time and use charts to track and communicate each session to coaches intuitive and user-friendly. This involved little to no data processing to produce usable data for coaches. With Catapult, these metrics were available but required some data processing to view trends over time. However, if the user aims to focus on specific metrics and keep the use of the data simple, Catapult’s home screen is streamlined and allows for easy toggling to monitor sessions.

Considerations Within Data Management: Tagging Sessions

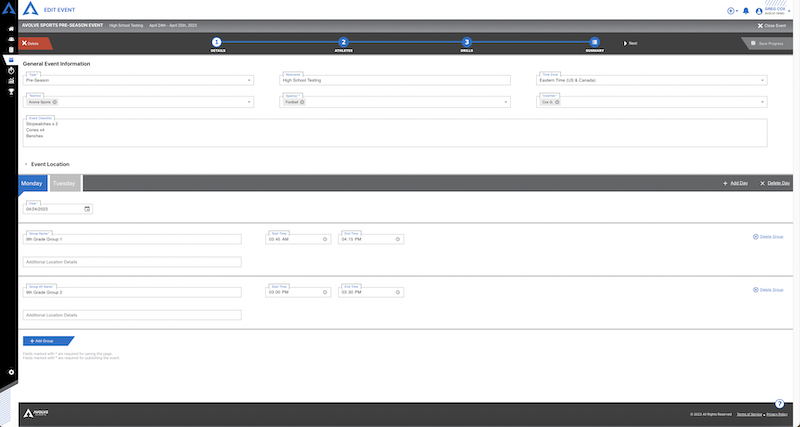

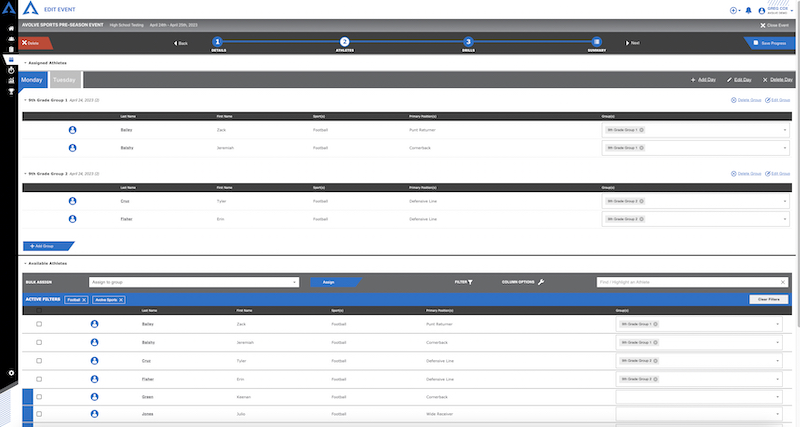

The next question to ask is: How does the operating system allow you to tag practice and speed sessions?

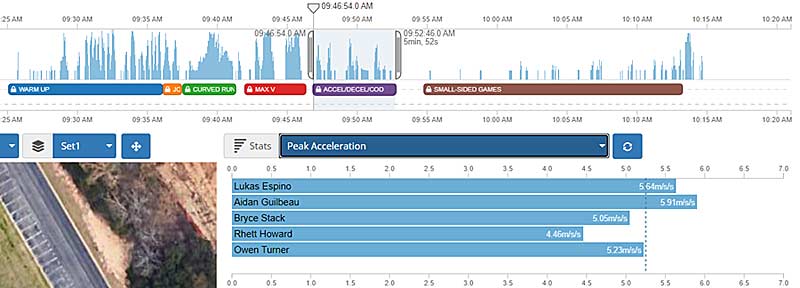

The ability to ‘tag’ practices and competitions into smaller segments to identify each drill and segment’s demands is one of the most useful tools for incorporating a comprehensive GPS plan. Share on XMost providers allow you to “tag” practices and competitions into smaller segments to identify the demands of each drill and segment. This feature also lets you compare segments of competition with the physical outputs of the athletes. The “tagging” process is different for each provider.

- In Catapult’s platform, you can add tags to each session while syncing the pods or editing the session. After the initial session sync, you must resync the session and review it from the home screen if you want to add tags later.

- Titan allows the user to create a library of tags and, using a slider bar, identify the segment to be named. From here, users can review each segment of the sessions and easily change the metrics they want to view.

Tagging is one of the most useful and necessary tools for incorporating a comprehensive GPS plan. I must be able to identify the demands of practice periods and games but also track the work/rest demands being placed on our athletes.

Tagging practice allows me to ensure that our more intense periods of practice that are designed for contest prep meet the demands by matching a load/minute prescription. I must be able to filter this data to identify the segments of practice that meet these demands; thus, an efficient tagging process is crucial.

Considerations Within Data Management: Communicating for Success and Efficiency

Another important consideration in this process begins prior to purchase: a conversation with the sport coaches. GPS allows practitioners to identify trends in intensity and volume, monitor athlete performance, and identify potential needs for load prescription changes. One example is a volume spike. This could indicate fatigue, or it at least warrants monitoring athlete performance following this exposure to increased demands—think of a second-string defensive back being thrust into a starting role.

In an ideal scenario, conversations would occur with team decision-makers to account for potential trends in these spikes and prepare a practice plan with drills that account for the physiological needs of the competition. Some performance coaches are in situations that allow for an increased role in decision-making, and others are not. Before acquiring GPS, these conversations should occur to ensure that all parties are on the same page regarding the sport coach’s willingness to include the performance coach in this process.

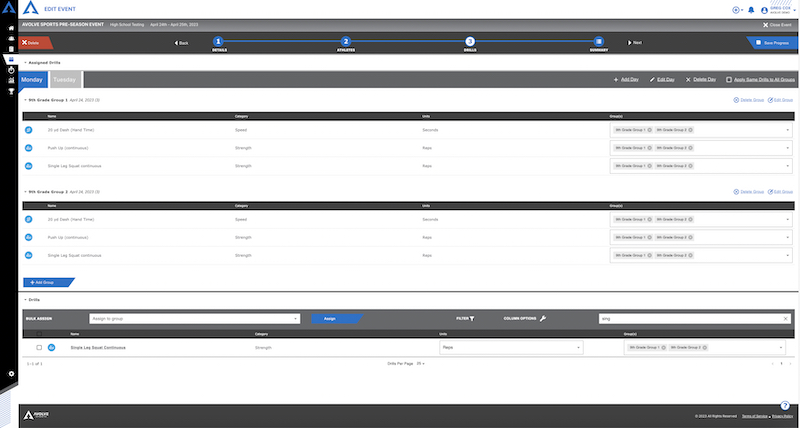

For programs using this inclusive approach, you must be able to effectively communicate practice and game data with coaches who structure practice. Report data is a crucial piece to increasing efficiency.

With Catapult, users select metrics each session and export them to a PDF that can be emailed to coaches. Titan allows users to create custom dashboards with comparison metrics for individuals and team or position group averages. Once the user creates the dashboard, the dashboard is saved for any future use. Following each session, the coach can download the PDF and send it to the coaches.

The use of dashboards and report profiling for athletes over the course of an athlete’s career can provide valuable insight into the growth of an individual over four years. Again, efficiency in this process is key.

Customer Service Matters

Finally, the relationship between the provider and the client matters. Inevitably, the tech will not function properly, and troubleshooting must occur. When these issues arise, I, as a consumer, expect that compensation for the service will also provide support for the product when needed, just like when I have issues with my phone, I can take it to my service provider for a fix.

For instance, following a session, I forgot to turn our units off and not only proceeded to leave them on overnight but also drove across the state. I made one call to the provider, and they assisted with info on how to sort out all unwanted data because my athletes, in fact, do not run 81 mph. (Don’t judge me before you drive through Atlanta…)

If you’re in the market for wearable GPS, talk to multiple COACHES, not companies, to gain insight into these considerations and identify which product fits your unique scenario. Share on XSome companies advertise excellent customer service when, in reality, certain clients are prioritized in order to support certain levels of branding that favor the company. If you are in the market for wearable GPS, I recommend talking to multiple COACHES, not companies, who use different providers to gain insight into each of these considerations and identify which product fits your unique scenario.

GPS at the High School Level? My Experience

When I navigated a move from private-sector training to high school athletics, technology was an afterthought in my mind—I thought systems such as VBT, force plates, iPads at each rack, and laser timing systems were for the elite college programs and the occasional private school. This misguided view was largely due to ignorance on my part, but there is no denying that high school athletics have found technology, and they’re never going back.

My first exposure to GPS came at the University of Cincinnati, where I was fortunate enough to intern under Coach Brady Collins and the football performance staff. During this time, I saw how Coach Jeremiah Ortiz, who was in charge of GPS management, used GPS to monitor athlete performance and workload. I was blown away by the capabilities and endless options GPS offered, but I still wasn’t sold on its usefulness in the high school setting. I realized that, at the collegiate level, monitoring workload was crucial to managing athlete health and wellness. But were my high school athletes exposed to high enough outputs to require monitoring?

Enter Mark Hoover.

You probably live under a rock if you don’t know Coach Hoover. I’m joking, but seriously, he’s a coach you need to know, especially if you use any technology in your performance program. Coach Hoover and Coach Jon Hersel visited Cincinnati for a Glazier Clinic in 2019, right before the world shut down. They were gracious enough to sit with me for almost three hours and discuss everything from GPS and VBT to general training philosophy. During this conversation, I distinctly remember, while discussing GPS, saying, “I understand the need for GPS at higher levels, but I’m not certain that my athletes are experiencing volumes and intensities that require load monitoring.”

Coach Hoover looked at me and smiled as if he had been waiting for that statement and said, “Coach, if you’re not measuring what your athletes are exposed to, at best, you’re just guessing (the game demands).” This hit me like a ton of bricks. All along, I had assumed that our athletes weren’t experiencing a meaningful nervous system impact. Again, ignorance on my part.

GPS is an increasingly common tool in the high school setting, and I can attest that GPS has helped us win ball games and keep athletes healthy at the high school level. Share on XFast forward a couple of years, and now GPS is an increasingly common tool in the high school setting, and I can attest that GPS has helped us win ball games and keep athletes healthy at the high school level.

GPS is a powerful tool, but without a streamlined organizational system to manage this data, coaches can be easily overcome by the amount of data and metrics a provider can give. Careful consideration should be taken when selecting providers to partner with to avoid simply going for a name brand at the cost of effectiveness and efficient use, ultimately leading to a poor consumer experience and poor use of what most of us are short on—funding.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF