Push-ups are an OG. A face card in the deck of (useful) exercises. In fact, they may be the only movement left unscathed by the myopic mission of boxing up exercises as “right” or “wrong,” better or worse.

Push-ups are old school, cool, beneficial, hard, and perhaps more technical than many people realize. They require dynamic stability and global coordination literally from head to toe, and you’re relying on a relatively small joint (the elbow) to bend and lower the body to the floor and back up again. And while they may be fillers—or “vanilla” for some populations—belonging to the body weight category doesn’t relegate them to the “dummy-proof” column or provide a simple check for “upper body push” if athletes can’t perform them correctly.

Although the title and content of this article focus on push-up development specifically for females, there are parts applicable to everyone. Being male does not provide an automatic proficiency pass for push-ups or exclude athletes from thorough coaching, just as being female does not call for belittling or misogynistic modifications. Every athlete deserves thorough and attentive training and coaching—but programming the same blanket training for males and females overlooks major developmental differences and does both a disservice.

Programming the same blanket training for males and females overlooks major developmental differences and does both a disservice, says @rachelkh2. Share on XTo provide the best possible training, one should be knowledgeable and respectful of differences regarding ability and long-term progress. This piece is not intended to examine comparisons between males and females but, rather, to discuss some reasons why training should vary and how to approach those differences.

My purpose is to:

- Provoke more thought and attention when it comes to prescribing push-ups for all athletes.

- Discuss two critical developmental changes that affect the physical performance of females during and after puberty and how these changes can impact upper body strength development.

- Provide insights and progressions that have worked for my athletes.

Developmental Considerations

Puberty is a complex, dynamic process, to say the least. There are significant hormonal, anthropometrical, and neuromuscular changes (among others) that can impact physical performance. For those in a position to govern physical activity or prescribe training to adolescents, it’s vital to understand these comprehensive changes. Typically, girls begin puberty and experience changes earlier than boys, ranging in age from 9–11 years old1–3, but the timing and rate of puberty can and does vary widely amongst individuals.

Although numerous changes occur during the adolescent period, there are two in conjunction that, in my opinion, are the most significant when it comes to the development of relative upper body strength and primarily impact adolescent athletes.

1. Peak Height Velocity

In both females and males, there is a time of peak height velocity (PHV)—also called the adolescent growth spurt—which coincides with the onset of puberty.3 During PHV, the long bones of the body, including the femur and tibia, undergo rapid vertical growth.1,4 Accompanying the increase in height is an increase in the center of mass (COM), making control of the trunk more challenging.4

As mentioned, push-ups require a coordinated effort by nearly every joint in the body; there isn’t a joint from the hips upward that isn’t involved, with the pelvis and spine being most heavily involved in providing support and structure for the entirety of the trunk. This will be covered in more detail to follow, but it is an essential pubertal change to be aware of for more reasons than just push-ups.

2. Strength and Neuromuscular Control

Following the growth spurt (PHV), it has been documented that girls do not experience what’s referred to in the literature as a neuromuscular spurt. That is to say that in conjunction with an increase in height, center of mass, and body mass, there is not an equal response in neuromuscular strength and coordination to match or pace the other variables of growth.5,6

“In lay terms, growth results in larger machines in both sexes, but as male subjects mature, they adapt with disproportionately more muscle “horsepower” to match the control demands of their larger machine. Female subjects do not show similar adaptations.”6

This difference is most notable with upper body development: “The disproportionate strength increase is most apparent during male adolescence, and is greater in the upper extremities than in the trunk or lower extremities.”7

This is not to say that strength does not increase—it has been documented that strength does increase linearly in girls. However, there is not a marked or observed time of peak acceleration.2

Although we can observe sexual dimorphism at this phase of development, it’s essential to adopt the mindset that these are not reasons why girls cannot do push-ups, but rather why prescribing upper body strength work should be distinctly different in certain regards and why painting your girls and boys with the same brush is not providing each with the training they need.

Positions

Before we can teach athletes how to navigate a more global pattern like push-ups, it’s important to address specific positional awareness of their pelvis, head, and scapulae. This part gets a bit nitty-gritty, but it creates a foundational footprint for further training. It is blatantly low fruit that seems to be largely forgotten in the early stages of athletic development.

Before we can teach athletes how to navigate a more global pattern like push-ups, it’s important to address specific positional awareness of their pelvis, head, and scapulae, says @rachelkh2. Share on XFor lack of creativity, I use the term “bony structures” because it simply involves teaching how to move parts of the axial and appendicular skeleton. Without teaching this prior to further push-up work (or other lifts), we end up with a roomful of athletes stuck in extension, hanging on their structures.

For a visual, I ask four students to stand in a square pattern and have the class imagine the four standing are holding a corner of a huge blanket. Then I ask what would happen if I poured 10 gallons of water in the middle. The answer, of course, is that the center would sink to the bottom, if not pull the corners out of the participants’ hands.

This is a true walk-before-you-crawl approach because even before the most basic of movements, like planks, the ability to manipulate these areas into their most advantageous positions is an essential piece of development. I partly attribute the need for work in these areas to PHV and changes in COM. However, it is plausible to include lifestyle factors as well as early specialization as reasons for this unawareness.

1. Posterior Pelvic Tilt or Anti-Extension: We’ve all witnessed athletes who attempt to perform a plank or push-up, but their belly button sags to the floor due to lumbar hyperextension. This puts stress on the individual facet joints but can also be unhealthy for the shoulders, as we can often observe the scapulae dive forward in accompaniment. This is corrected by teaching posterior pelvic tilt or anti-extension of the lumbar spine. We can correct it by teaching anti-extension exercises like dead bugs.

In my experience, the easiest and most effective way to introduce this is in a supine position and then transition to a prone position, as it’s specific to push-ups and other prone exercises, like fallouts or ab wheel rollouts.

2. Cervical Retraction: Typically, we can also observe pronounced cervical extension, where the head is in front of the body or the eyes are looking upward. Correcting this involves teaching how to retract and protract the neck. I’ve found a seated position to be the best place to start, then prone. In a prone position, we begin to increase strength, as it provides gravitational resistance. Cervical retraction, like the posterior pelvic tilt, is a small but binding piece of a bigger movement puzzle. Forgoing the instruction of either leaves other movements, like RDLs, lacking.

Video 1. Example of cervical retraction in a seated and then a prone position.

3. Scapular Protraction and Retraction: Based on my experience, there will always be athletes who don’t know how to move their scapulae around their rib cage. This is important for successful pushing and pulling movements and helps prevent unwanted elevation or anterior tipping in movements like push-ups. Again, I teach this in a general way, first in a seated position, instructing them to feel their shoulder blade, then in a prone position. Teaching this early paves the way for correct rowing, vertical pulling, and pushing techniques.

Video 2. Example of shoulder protraction and retraction.

Progressions

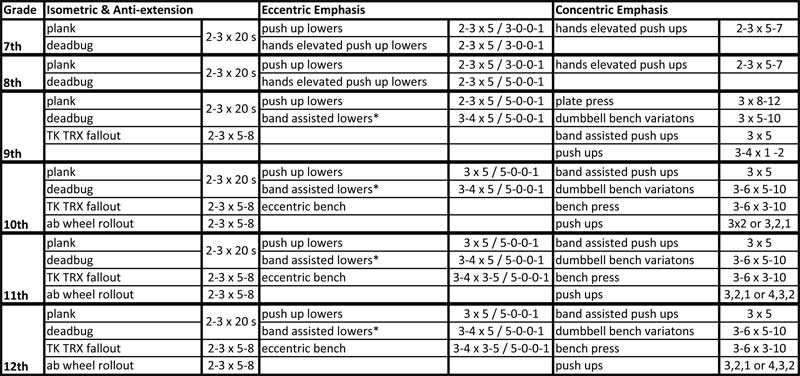

Push-up execution is a marathon process, requiring diligent and thorough coaching. The most successful approach I’ve found is establishing a strong isometric base, then progressing to the eccentric and concentric simultaneously, but in different ways.

This is also where I’ve observed the most significant difference between genders. Girls will need more time developing concentric pushing strength before they’re able to do full push-ups, whereas, with boys, I’ve found the positional work to be most needed. The most important thing is to meet your girls where they are rather than rushing them to a specific endpoint. Be creative and find ways to help them be successful.

Girls need more time developing concentric pushing strength before they can do full push-ups, whereas, with boys, I’ve found the positional work to be most needed, says @rachelkh2. Share on XWeight rooms are obviously full of weights, and they can be utilized in numerous ways, their primary design aside. For instance (noted in my progressions chart below), before we get into more traditional bench variations, I have my girls use bumper plates to train their pushing strength. I think in many cases, depending on the age group, this is a superior place to begin—for us, it’s also out of necessity due to a lack of appropriate-weight dumbbells.

Recently, Alan Bishop tweeted some great information about the strength deficit between maximal eccentric and concentric capacity. Essentially, the ratio of eccentric strength to concentric will always be greater. However, by emphasizing the eccentric, we can further widen the “gap,” theoretically bringing up concentric capacity. And to steal another point from Alan, I have no double-blind studies to back this up when it comes to submaximal or relative strength application, only anecdotal experience and 46% of all my female athletes demonstrating the ability to perform technically sound push-ups at the close of the 2021–2022 school year.

To return to the eccentric ratio, once we establish positions, we progress to the eccentric, or lowering part, of the push-up, while maintaining those bony positions. Although the concentric, or “up” phase, may be lacking for some, the isometric and eccentric phases are at work here and, as we know, are a strong stimulus for strength. This is also important to build the pattern-specific neuromuscular coordination that is so vital at this time.

*as needed to continue reinforcing correct positions.

Isometric: With my middle school athletes and incoming ninth graders, we spend a lot of time developing positional strength using planks. As with other movements, good positions should be established first. With push-ups, it begins with planks. Yes, they’re boring, but not entirely useless. And while there are better ways to train bracing, planks are a powerful precursor to push-ups. They’re an isometric classroom when we consider the number of structures that can be manipulated and strengthened: posterior pelvic tilt, cervical retraction, end range shoulder protraction.

Planks are an isometric classroom when we consider the number of structures that can be manipulated and strengthened: posterior pelvic tilt, cervical retraction, end range shoulder protraction. Share on XIt’s essential to establish positional awareness in this static position because if they struggle with a plank, they will fail in a more dynamic progression. Once they get to high school, I begin progressing their anti-extension movements, as seen in the chart.

Note: I think external load can be successfully used with middle school athletes, depending on your circumstances. I have very large groups, with both limited equipment and space, so we maximize body weight, tempo, and positions, which has worked well.

Eccentric: Once they can demonstrate a plank, keeping their lumbar and cervical spine out of extension, in 20-second intervals, I add the eccentric portion. However, it’s common for them to default back to extension patterns. For this reason, I incorporate hands-elevated lowers, but band-assisted lowers are preferred, as they allow for a full range of motion. And depending on the group, I’ll utilize a two- to three-week eccentric bench phase to continue accentuating the strength deficit.

Video 3. Athletes demonstrating the eccentric, or lowering portion, of the push-up while trying to maintain bony structures.

Concentric: I think progressions can be taken to the extreme, and at some point, the athlete just needs to get stronger. However, if we’re “slow cooking,” putting a barbell in the hands of a novice with no requisite skill patterning is contradictory and short-sighted. Progressions provide checks for proficiency, safety, and confidence. They bridge one movement to the next and set athletes up for success.

With these progressions, I often use more than one in conjunction with another. For instance, the bench press may serve as our primary upper lift, but I’ll include push-ups or band-assisted push-ups as accessory work within the same lift. Coaches should note that once an athlete can perform a full push-up, it is important to prescribe them in lower volumes, so they can complete quality reps and continue to get stronger. Don’t crush their confidence to satisfy your ego-driven goals.

Video 4. Concentric pressing progressions: plate press, DB bench, bench, assisted push-ups.

Push to Close

If our goal is to build strength and develop skills for the long term, we need to step back and take a part(s)-before-the-whole approach, even with bodyweight movements. For females, push-ups are more of a reflection of strength than a foundational strength builder. And with novices, I don’t think prescribing them is realistic or feasible until the other aspects of strength and control are established.

With novices, I don’t think prescribing push-ups is realistic or feasible until the other aspects of strength and control are established, says @rachelkh2. Share on XVideo 5. Athletes performing sets of push-ups.

This can be a rewarding and meaningful process for girls, and trust me, they want to be able to do push-ups and demonstrate their upper body strength. Help them reach these goals in a way that challenges them but also empowers them to keep pushing—no pun intended (well, maybe).

We must meet our athletes where they are, and failing to observe and serve their present state is an oversight. Coach the needs of the athlete in front of you and set them up for success. This may entail differences in programming and progressing, and that’s okay; it’s to be expected. Rather than dismiss the differences in our athletes or blanket them with the same training, we need to embrace and understand their differences to help them succeed.

*Author’s Note: This article is dedicated to Dr. Shelley Long, who’s taught me more about strength than any weight room ever could.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Soliman A, De Sanctis V, Elalaily R, and Bedair S. “Advances in Pubertal Growth and Factors Influencing It: Can We Increase Pubertal Growth?” Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. Nov 2014;18(Suppl 1):S53–S62.

2. Beunen G and Malina RM. “Growth and Physical Performance Relative to the Timing of the Adolescent Spurt.” Exercise and Sports Sciences Reviews. Jan. 1988;16(1):503–540.

3. Rogol AD, Clark PA, and Roemmich JN. “Growth and Pubertal Development in Children and Adolescents: Effects of Diet and Physical Activity.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. Aug. 2000;72(2 Suppl):521S–528S.

4. Myer GD, Chu DA, Jensen EB, and Hewett TE. “Trunk and Hip Control Neuromuscular Training for the Prevention of Knee Joint Injury.” Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine. July 2008;27(3):425–ix.

5. Hewett TE, Myer GD, and Ford KR. “Decrease in Neuromuscular Control About the Knee With Maturation in Female Athletes.” Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. Aug. 2004;86(8):1601–1608.

6. Hewett TE and Myer GD. “The Mechanistic Connection Between the Trunk, Knee, and Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury.” Exercise and Sports Sciences Reviews. Oct. 2011;39(4):161–166.

7. Beunen G and Malina R. “Growth and Biologic Maturation: Relevance to Athletic Performance.” In The Young Athlete. April 2008.