Barbell training matters more than ever.

When gyms reopen and things go back to “normal,” the barbell will summarily return to prominence. A steady diet of bodyweight workouts, 5K runs, and anything that can be done with a kettlebell or dumbbell that’s appropriate in a confined living space will have athletes and the general population running back to the rack. Why? Because athletes need stress to grow, and we haven’t found better ways to apply stress. If we had, we’d be using them by now.

It’s easy to promote research about how training cessation of two, four, and nine weeks don’t affect maximum strength levels. But this is a simple, small-world comparison. Strength, while important, is not wholly about decelerative qualities, coordination, and tissue robustness. I’ve found cessation of training and the subsequent detraining to be a rather idiosyncratic process. Some athletes seem marginally unaffected, while others see pretty rapid decreases in only a short space of time. What this current time off from training means to athletes varies on a case by case basis.

I recall Dan John writing, “Off the top of my head, I would suggest that a hard training individual take about six weeks off a year. And, I mean off: no basketball tournaments, no aerobics classes, nothing. Now, the sad thing is this, basically, those of you who do not train hard just decided to take the next six weeks off. Those who train hard will take those six weeks off when they are dead. I never understood taking time off until far too late in my career. ”

The inability to train is a nightmarish ordeal for most athletes. They will want to lift, so what is the plan or the strategy, asks @WSWayland. Share on XFor most athletes, the idea of training cessation is a nightmarish ordeal when one’s identity is wrapped up in being an athlete. Having research that tells them they won’t get “much” weaker is little solace when facing something emotive like training status. Athletes will want to lift, so what is the plan or the strategy? Well, prudence tells us one thing. It’s better to underestimate an athlete’s physical preparedness by a lot than overestimate by a little (Mladen Jovanovic).

Prudence tells us one thing: it's better to underestimate an athlete's physical preparedness by a lot than overestimate by a little, says @WSWayland. Share on XThe payoff is not symmetrical. To paraphrase Kier Wenham Flatt, those who go in hard at week one will probably end up sipping on “sappucinos” the rest of the season. We know sudden spikes in training load increase injury risk, and that chronic dosing protects against it. It’s equivalent to a fighter feeling out his opponent rather than rushing in and catching a flying knee. We need to get athletes to a point where they can do the dance of training once more.

There will be an understandable situation of potential weight room stratification between the haves and have nots of the home training world. We’ve seen plenty of social media evidence that some athletes have beautiful home gym set-ups. This is all well and good for a multimillionaire athlete, but not much help to an amateur Olympian living in a central city apartment. In individual sports like golf and combat sports, I deal with athletes on a case by case basis. When my local rugby team steps back into the facility, I know it will be better to take Mladen’s overcautious approach.

Methods to Get Athletes Back in the Rack

I was going to write an article covering my general physical preparation (GPP) approach, but Jacob James of Crusader Strength posted an article that’s pretty close to my own Cal Dietz-inspired twist on this set-up. Also worth checking out is Rachel Hayes’ post covering the intent of GPP even in specialized athletes. My aim is not to write another GPP article. Athletes will want to resume barbell work, especially those who trust it and understand its value in their efforts to return to strength.

Athletes will want to resume barbell work, especially those who understand its value in their efforts to return to strength, says @WSWayland. Share on XThe first step will be to get the measure of the individual. It’s simple to assume weakness, but surely a better approach is to measure it. I suggest two key strategies that I plan to employ. First is some sort of max strength testing with nearly no technical overhead. Something simple like an isometric mid-thigh pull belt squat iso that Carl Valle has demonstrated on Twitter would be ideal. If we can get the measure of an athlete in a time-efficient manner, we can plan accordingly. This test, however, is somewhat redundant if you don’t have decent pre-training cessation measures, but it will still act as a baseline.

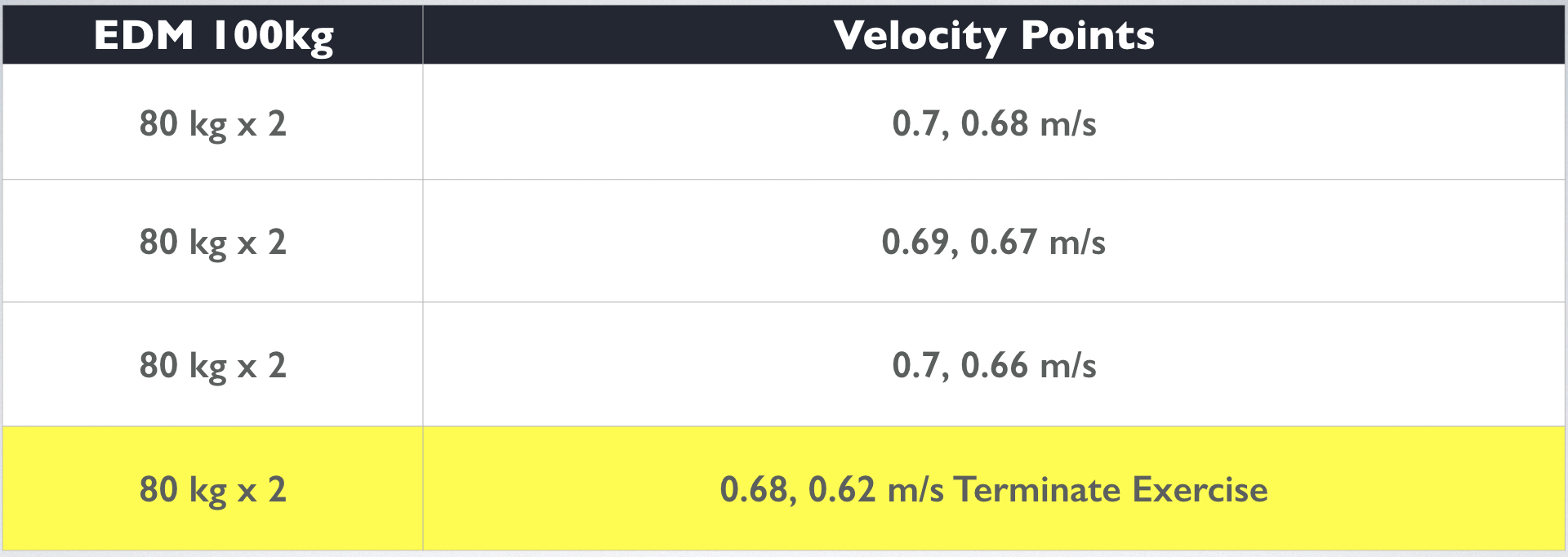

Second, use VBT to monitor submaximal testing of some variety on your preferred KPIs. The beauty of this approach is that velocities dictate loading rather than using loading alone as a performance measure. You can then keep using VBT measures over the acute introduction to training into the chronic training phase.

Stimulate—Do Not Annihilate

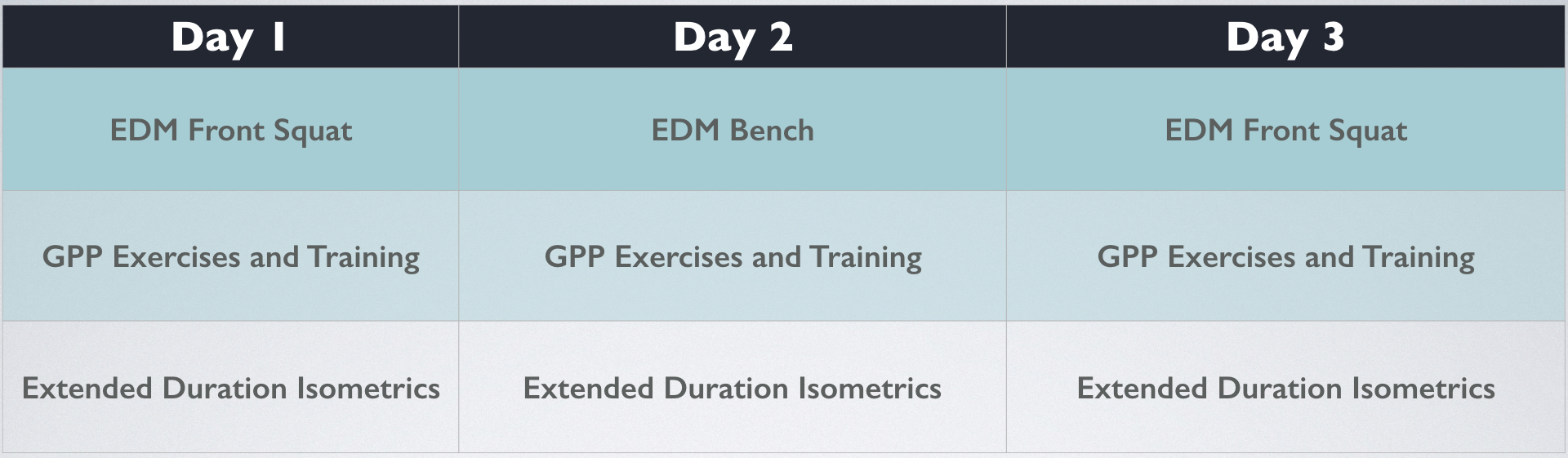

I plan to employ the GPP Sandwich, which involves working to an everyday maximum (EDM). What is EDM, and what is it not?

Competition Maximum (CM) is a level of performance achieved under a major arousal of the competition. For some athletes this arousal might be too much, so the CM can be lower than Training Maximum. But generally, CM is the highest level of performance, in this case 1RM.

Training Maximum (TM) is a level of performance that can be achieved in training conditions. It still needs some arousal, but not as much as in competition. This is the level of performance when you put your favorite death metal track, ask for assistance and cheering from your lifting partners, ask for hot chicks to watch and slap yourself few times. It is “balls to wall” as it can be achieved in training conditions.

Every Day Maximum (EDM) is a level of performance that you can achieve without any major arousal, music or hot girls in the gym. Something you can lift by just walking to the gym, and listening to Mozart. Hence the name “every day maximum.”—Mladen Jovanovic

EDM speaks to the idea of “raising the floor”—that most of the progress you make will come from submaximal training at submaximal intensities rather than aiming for regular training spikes. How do we apply this in a gym setting? Simply get the athlete to work a single maximum on any KPI lift. There should be no arousal intensification strategies, no triple espresso, no thrash metal, and no back-slapping. The athlete then moves on to whatever GPP strategy you had planned.

The everyday maximum approach gives athletes the freedom to show they can push themselves and be constrained, says @WSWayland. Share on XThe strategy has two purposes: safe working maximums to give you something to work off and something the athlete can chew on that isn’t just GPP. Making athletes feel strong is a useful tool in training resumption. The key is keeping athletes on a tight leash while treating them like grownups. Much of the conversation that’s surrounded athletes’ return to sport treats them like training automatons. The EDM approach gives them the freedom to show they can push themselves and be constrained.

Finishing sessions with extended yielding isometrics is a great way to encourage muscle growth and tendon health. I took this method from Christian Thibadeau: “2-3 sets of 45-75 seconds at the position where you can create the most tension in the target muscle. Don’t just hold the weight, flex the muscle as hard as you can.” The mixture of loaded stretching and yielding isometrics at the end of a session leave the trainee feeling worked but with minimal blowback. The mechanisms Christian suggests are:

- It’s effective at activating mTOR, which triggers protein synthesis.

- It’s (with occlusion training) the best way to increase the release of local growth factors because it combines muscle hypoxia (lack of oxygen) due to the constant tension and stretch (both reduce blood flow and oxygen entry into the muscle) and large lactate accumulation.

- When used for the proper duration (45-75 seconds) or at the end of a set, it creates significant muscle fiber fatigue.

Hand-Supported Squatting

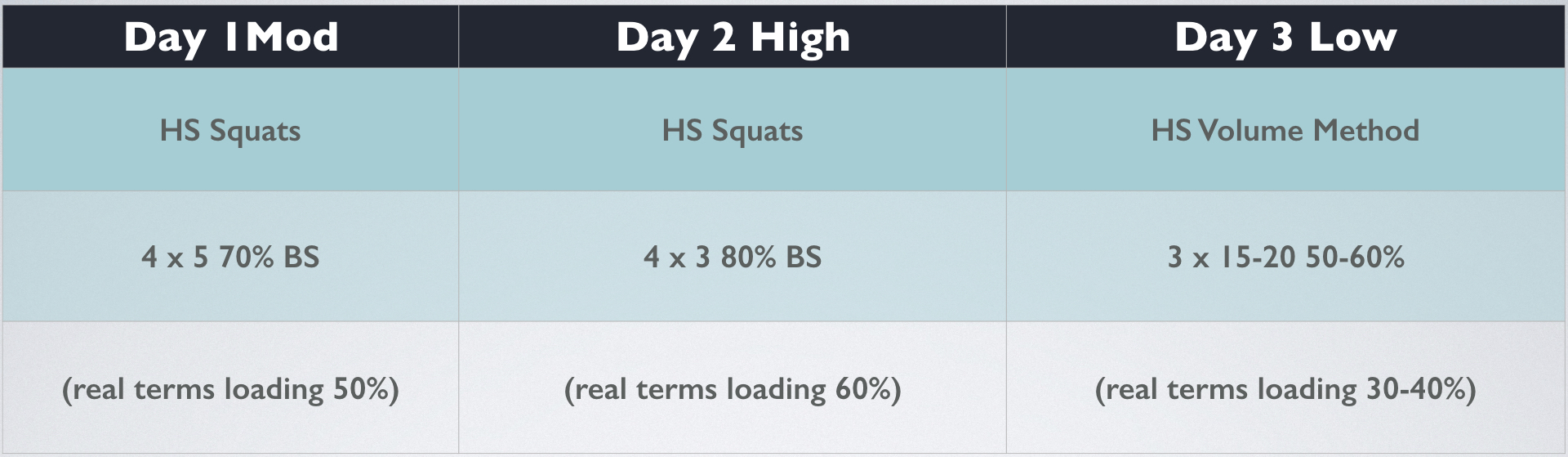

You would not expect an article from me without mention of hand-supported movements. Submaximal hand-supported squatting is one of the return to play (RTP) protocols I use with injured athletes, and it definitely fits the bill here. Cam Josse once described it as “a great way to feel strong again.” Generally, the hand-supported squat tacks at about 120-125% of your back squat maximum. The RTP protocol I use is to program hand-supported maximum the same as 100% of the back squat. The athlete gets to move load and train in what feels like a normal loading arrangement. We get lower loading in real terms, but we get to groove the squat pattern, allowing the athlete to “feel” load for a few weeks before moving on to conventional barbell work.

Hand-supported squats let athletes groove the squat pattern & *feel* load for a few weeks before resuming conventional barbell work, says @WSWayland. Share on XHand-supported squats also reintroduce compressive forces that may have been missing for a while—something you won’t find doing bodyweight squats or overhead squats with a mop. Another approach is a volume and range method. Use moderate loads, usually 50-60% of HSS max, and perform 15-20 reps of full range of motion squats allowing for full hand assist on the way up and down.

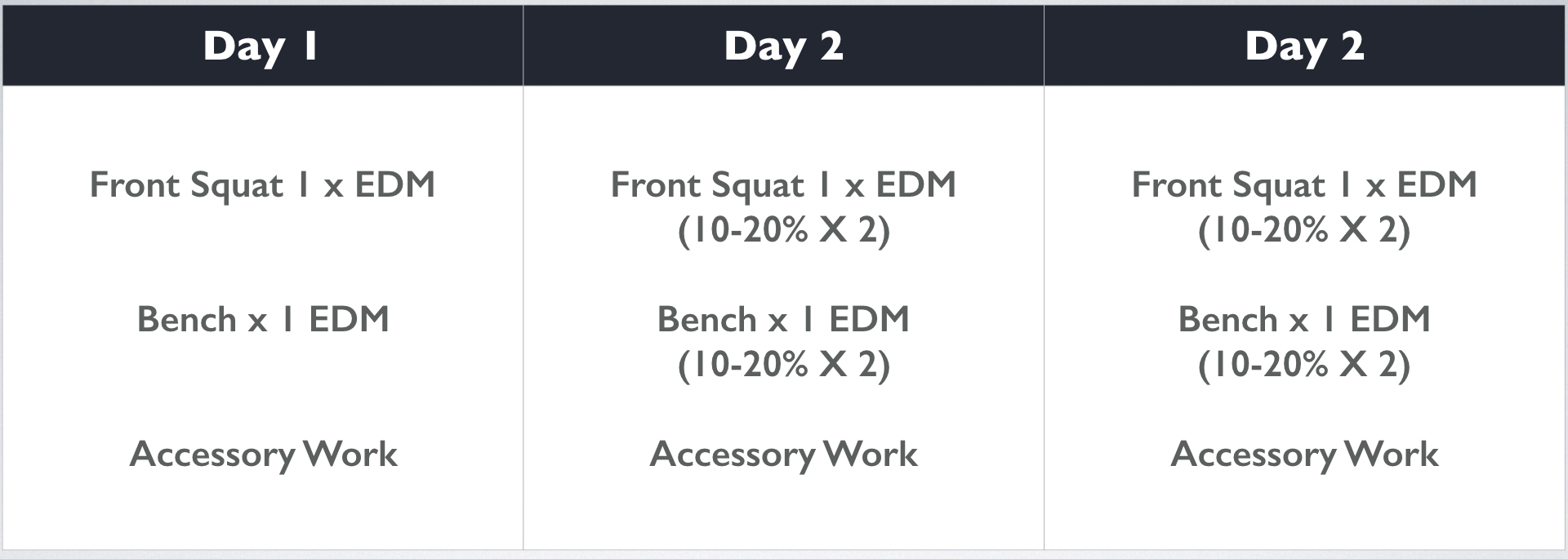

EDM and Walk Away

Another acute approach I like after a training break is building volume into the EDM concept. Linearity gets a bad rap—for acute training, it can serve as a smooth slide into conventional training. The athlete performs an EDM single and, on subsequent days, builds volume via back-off sets. In subsequent sessions, you perform back-off sets from your EDM, taking off 10-20% and perform a double and linearly build volume over just two weeks before moving to a more conventional approach. This somewhat borrows from an old Dan John approach I once used performing 1-2 sets of double on my front squat at 80% for two weeks.

Also, try front squatting at the start of EVERY workout for a week or two. Nothing crazy, maybe two sets of two, with around 80%, then a single at some higher weight. Some of us need the “Nervous System Stimulation.” I just invented that, but it seems to help. The way to learn a language is to immerse yourself into it, perhaps you need to immerse yourself in your legs.—Dan John

Nervous system stimulation is right, as the idea is to groove the squat at reasonable load but without exhaustive levels of loading. We can apply the same principle to any lift. The ethos running behind this is: stimulate do not annihilate. I suggest building up to no more than 3-4 sets in the 2 weeks. Alternatively, use a velocity measure to track drop off on the back-off sets—something like a 5-10% threshold should do it, using the best rep as the baseline.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Fabio Sarto, et al., “Impact of potential physiological changes due to COVID-19 home confinement on athlete health protection in elite sports: a call for awareness in sports programming,” SportRxiv Preprints, April 22, 2020.

2. Dan John, “The Front Squat,” (blog).