Whether in training, a profession, or in life itself, balance is a key piece to sustained longevity. The pendulum can’t swing too far in one direction or else it leaves us susceptible to unfavorable outcomes (injuries, burnout, chronic stress, cognitive bias, etc.). For us coaches that train team sport athletes, balance is a major concept on which we hang our hats. A really solid team sport athlete is typically a Swiss army knife throughout their development. They are solid at just about everything, from both a physical and mental standpoint: they are simply what used to be called “athletic.”

For us coaches that train team sport athletes, balance is a major concept on which we hang our hats. Share on XThis athleticism is built through many sports, activities, and life experiences that have left them with a diverse toolbox to pull from in terms of movement solutions. As coaches, understanding this contrast can vastly improve the quality of athletes in our communities, along with the way we shape the development of these athletes from adolescence to their adult years.

Yin and Yang

Dating back to 3rd century BCE (or even earlier), Yin and Yang was a fundamental concept found throughout Chinese philosophy. The principle of Yin and Yang is that all things exist as inseparable and contradictory opposites, for example:

- female-male

- dark-light

- old-young

The pairs of equal opposites attract and complement each other. Neither Yin nor Yang is considered to be superior to its counterpart; instead, a correct balance must be struck between the two in order to achieve harmony. I posit that as physical preparation coaches, the most powerful fundamental understanding to have is that of finding the contrast and applying the contrast within your programs.

Organization of training

My decision to start the Common Sense Training podcast was partly influenced by my desire to highlight great coaches from all over the world. These coaches have had continued success and longevity over decades of working with athletes. One coach that I wish I could have had the opportunity to speak with was the late Charlie Francis. Charlie’s approach was unique in that it was applicable across any sporting activity and could be adapted easily by us coaches.

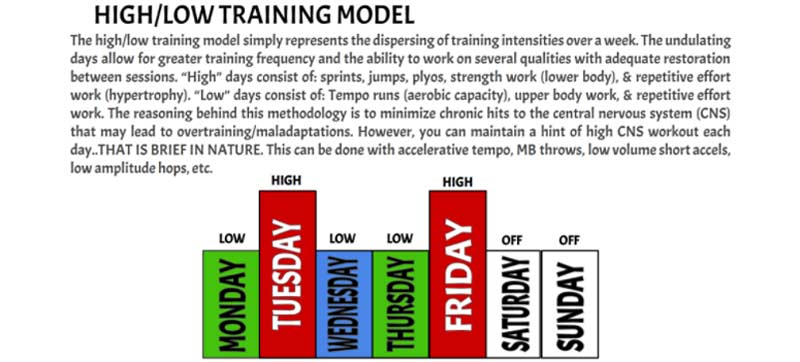

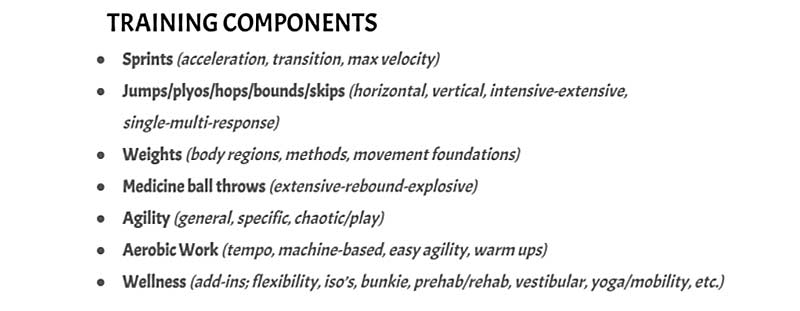

One of the hallmarks of Charlie’s coaching philosophy was his high-low approach to program design. In this polarized design, intensities would work in a contrasting manner in order to support the natural stress-adaptation rhythms of the human body. Some examples of the high intensity elements would include:

- maximal sprinting

- plyometrics

- medicine ball throws

- heavy strength training

- sport practice

- competitions

Low intensity elements would include:

- tempo runs

- aerobic activities

- strength circuits

- abdominal work

When utilizing this approach, it doesn’t mean that there aren’t certain forms of moderate intensity elements added in when needed.

Some reasons why contrasting intensities for athletes might be favorable are:

- If athletes are performing quality high intensity efforts, sustainability of those outputs must be preserved.

- Too much high intensity and volume can lead to excess fatigue, injury, burnout, etc.

- In terms of resource allocation, athletes only have a finite amount of energy which should be spent on the stimuli that can get them the biggest bang for their buck.

- Low intensity elements can be general in nature which can be used as a low cost means to build strength, lean mass, work capacity, etc. (doesn’t empty the “cup”).

- Athletes need to recover in order to adapt. Low intensity provides that buffer and assists in the adaptation process.

- Low intensity promotes recovery, resets tone, and helps rebound from high intensity sessions.

If athletes are performing quality high intensity efforts, sustainability of those outputs must be preserved. Share on X

In a recent conversation with coach Joel Jamieson, he talked about his recovery-driven process to training. Obviously, as coaches we have to give our athletes something to recover from in training. However, Joel makes a great point in saying an athlete can only get to a higher level of performance based on the status of their recovery from previous stressors.

Let’s use arbitrary numbers to work this out. Say an athlete has a readiness score of 100. They do a high intensity session and it brings that number down to 60. After a true high intensity session, an athlete might need 48-72 hours to fully recover (athlete depending). So, let’s say after 48 hours they have a recovery score of 80. They do another high intensity session and it drops them down the same 40 points as last time. This time, however, they started in a deficit—so now their readiness sits at a 40. You see where I’m going with this.

Yes, human beings aren’t so simple as a number on a page, but if you dig yourself deep enough into the rabbit hole of recovery, bad things tend to follow. We didn’t even take into account mental stress and how lifestyle choices affect the body’s ability to function. There is a point of diminishing returns. More is not always better. Having contrast in a program might help offset that if done properly.

Where We See Contrast in The Trenches

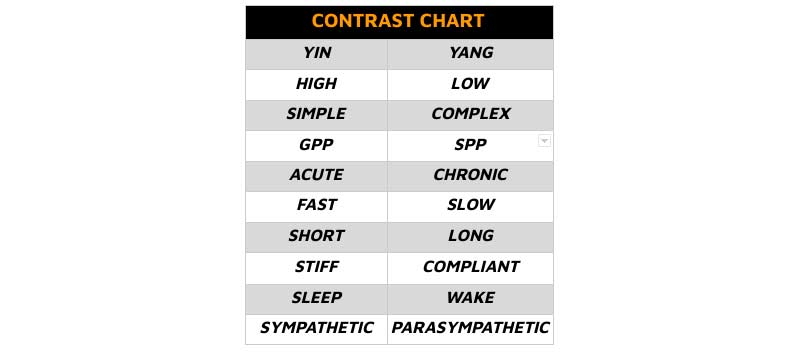

Contrast is present in many of our programs, even if we don’t realize it. Let’s take a look at some common forms of contrast that we may see in a physical preparation program.

Simple-Complex

In the words of legendary coach Boo Schexnayder “you can either be fancy or you can be intense.” The simple tools in training, like maximal sprints, jumps, tempo runs, squats, deadlifts, presses, chin ups, and many others, are fantastic ways to allocate your training resources. These menu items are simple to teach and oftentimes feel innate to athletes if they had appropriate exposure during their development.

Simple training can be used for all qualifications of athletes. If you are lucky enough to work with elite athletes, the simple training elements are ways to get in training while not zapping precious energy resources that are needed for their sport. Simple doesn’t necessarily mean easy. Simple means making training cut and dried enough where athletes can focus on execution and outputs.

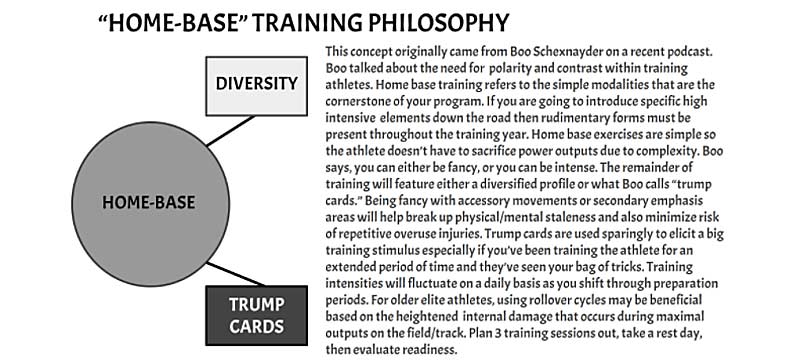

Two major forms of simple and complex are home base-diversity and general physical preparedness-specific physical preparedness. Home base is your simple, yet effective training modalities that are present throughout the entire program. If you know the vertical integration concept popularized by Charlie Francis, these would be the major components that are threaded block to block.

Every once in a while, diversity is needed in a program. Diversity can break up training staleness or be the trump card needed to drive a favorable adaptation. An example might be acceleration and max velocity. In team sports, acceleration training would be the home base. However, on a frequent basis you would want to sprinkle max velocity sprints to aid in top speed and to inoculate against soft tissue injury.

Diversity can break up training staleness or be the trump card needed to drive a favorable adaptation. Share on X

The other form that us coaches should all be familiar with is GPP-SPP. How this fits into the simple-complex framework is in the specificity of work. GPP will consist of general training aimed to boost general qualities. Typically, GPP work will be far away from the sporting actions, although it may hit on a specific quality like regime of muscular work or energy system development. The goal of GPP is to prepare the body for SPP.

SPP is what it sounds like. On the sliding scale of training, athletes will now begin training more concentrated activities and abilities that hopefully will transfer over to successful sporting outcomes. The distribution of GPP to SPP will be different for every level of athlete. Striking that balance of what needs to happen will take shape after a detailed needs analysis.

An easy example of a GPP exercise for a football lineman is a squat variation. It strengthens and prepares the hip and knee extensors. A squat variation can then transfer into a heavy prowler push in SPP. A coach can then match the sets, reps, distance, and rest intervals to match that of a football game. The exercise still focuses on the lower body, but in a more specific manner. It is important to note that true specificity is found in the sport itself—anything done in the weight room or during S&C drills is relatively still general in its application.

It is important to note that true specificity is found in the sport itself—anything done in the weight room or during S&C drills is relatively still general in its application. Share on XAcute-Chronic

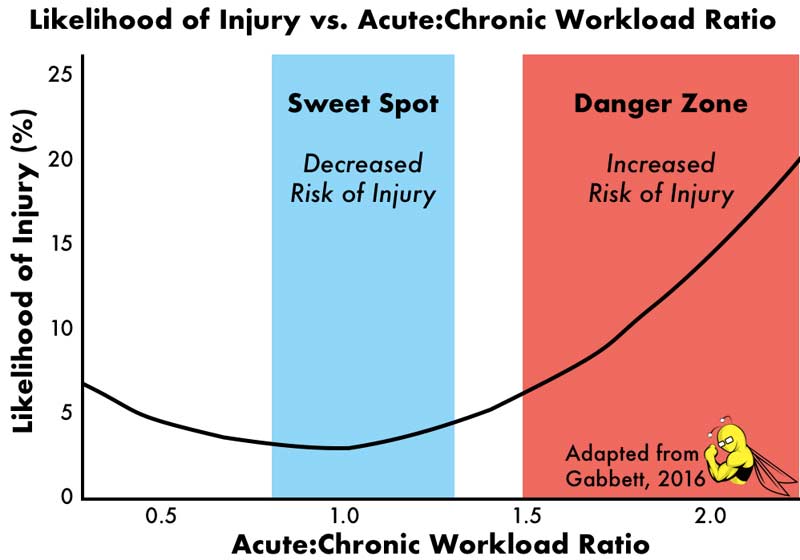

The sport science sector has begun to peel away some of the layers that relate to player loading and potential for injury. One area that has received a lot of interest is that of acute versus chronic stress. Acute simply means short term. Chronic would then be a long-term view of the stressors applied. It is important for us coaches to begin with the end in mind when it comes to preparing our athletes for their sport.

I recently recorded a podcast episode with coach Aaron Wellman where he explained the importance of gradually building up workloads as opposed to acute ramp-ups like we see in many training camp environments. Aaron uses the phrase “callous don’t blister” when talking with coaches. We also talked about the role of sport science in physical preparation. The goal of collecting data isn’t to give our athletes more time off or less work; the goal is to properly progress them in a safe manner that allows them to do more work over time.

That is the ideal situation. Having enough to slow cook athletes and nudge the needle to a place where they are hopefully prepared for the sport. It is important to remember that the first week of training camp is often the most intense period that an athlete will face all year due to the abrupt spike in stressors.

Another important area that Aaron believes to play a huge role in athletic performance is the accumulation of life stress. Training is just one spoke of the wheel. The sport they play is another. Mental stress, emotional stress, social stress, and lifestyle choices are all additional spokes to the performance and wellness wheel.

Visualize a full cup of water. The cup is our capacity to handle stress. Water is our energy. As we get stressed, we dump some of the water out. What happens when it’s all gone? Performance tanks, our bodies lose their ability to function optimally, we could get sick or run down, our resiliency is diminished, etc. Having that awareness as a coach will put us in a better place in terms of loading and having conversations with our players.

One small example for me personally is training my athletes during finals week. From a mental standpoint they are shot, but I have this wonderfully periodized plan and it is a high intensity day. Well, something has to change on my end. Not drastically though. Remember plan B is as close to plan A as possible. There is time where we can make some of this up; it doesn’t, however, have to be today. There’s a quote I like that says: “The intensity doesn’t come from the sheet of paper, it comes from the athlete.”

The intensity doesn’t come from the sheet of paper, it comes from the athlete. Share on XFast-Slow

There are many training modalities that come to mind when I think of fast and slow. My initial thought goes to a broad brush of what many team sport athletes might need: alactic power/capacity and aerobic capacity. Where these qualities may appear to be on opposite ends of the spectrum, you can adapt training to include both.

Alactic efforts are those that are very intense and brief in nature. Think maximal sprints, jumps, lifts, etc. Aerobic endeavours are best served at lower intensities with varying durations. The building or maintenance of aerobic capacities will support alactic outputs and allow for a condensed recovery period between repeated bouts. Aerobically driven activities are also non-competitive to the main alactic stimulus if programmed properly.

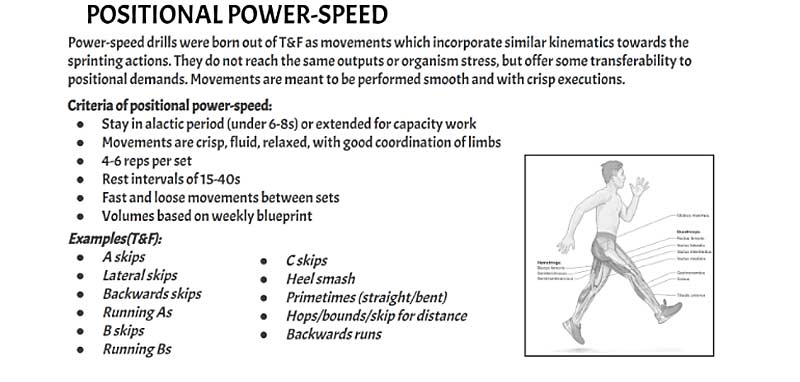

To paint a picture, think of training for sprinting-based activities. Our fast actions will include hard accelerations and maximal velocity sprints—these are meant to raise the ceiling of performance. But they also come at a high cost. To counterbalance our fast work, I will use “slow” training means. By slow, I am thinking of smooth tempo runs or running drills done extensively. Both serve as an important stimulus if dosed appropriately.

Another example of fast and slow could involve muscular actions—more specifically, eccentric and concentric. Both of these muscle actions are crucial in sports and movement in general. Eccentric muscle actions are typically done through lengthening and are fairly damaging compared to other muscle actions. Eccentrics are often referenced when we talk about “force absorption.” Concentric muscle actions are typically done through muscle shortening.

The concentric action is most commonly thought of as “force production.” There is growing interest in the eccentric portion of movement and its role in injury and performance. Something I hear frequently from coaches is that an athlete can only produce as much force as they can absorb—when that balance is too asymmetrical, that’s when injury risk creeps up.

There is growing interest in the eccentric portion of movement and its role in injury and performance. Share on XThe weight room is an obvious place to implement fast and slow movements. A good example could be shown with the squat exercise. To make a squat fast, you need to reduce load. Dynamic effort squats are done with 40-70% of your 1RM, using a controlled eccentric and a high intensity, fast concentric. This helps in the recruitment of motor neurons.

To slow the squat down, we can add a rep tempo. The rep tempo would bias towards a fairly slow descent; maybe like 4-8 seconds depending on load. This style of squat is often called eccentric training. Loading could be around 70-90% of 1RM and could even go as high as 120% of 1RM in qualified athletes.

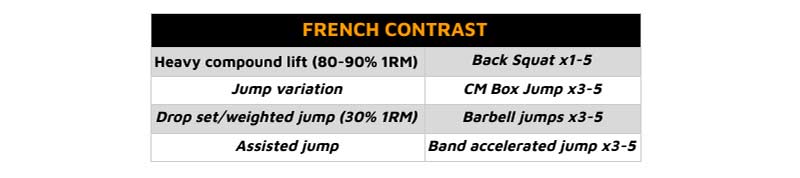

Another form of fast and slow is French Contrast training. French Contrast utilizes varying loads and velocities in an attempt to hit each major landmark along the force-velocity curve. Two major differences in French Contrast worth noting are that heavier loads are used without a slow eccentric. The heavy load itself will slow the movement down. The second difference is the use of assisted movements. These assisted movements help velocities reach a level that wouldn’t otherwise be hit. Here is a basic template of what a French contrast series might look like for the lower body.

Short-Long

Charlie Francis would often use a short-to-long or long-to-short approach with athletes. The basic premise was to manipulate sprint volumes in order to properly progress training in an effort to avoid “too much, too soon.” For team sport athletes, the short‑to‑long approach seems to make sense based on the running demands.

In many sports, the furthest an athlete might run unabated might only be about 50 yards. That number generally seems to be much less than 50 yards, but my recommendation is to train those longer distances for the “break glass in case of emergency” situations so the athletes don’t get injured. The two major variables to consider in a short-to-long program are volume and intensity. In sprint training, depending on the level of athlete, I’ve seen average volumes hover between 200-500 yards per session.

Developing athletes are able to handle higher volumes because they have less horsepower and won’t do as much damage as an elite athlete. The higher volumes also allow for more repetitions to develop proper motor patterns and sprint postures.

Developing athletes are able to handle higher volumes of sprint training because they have less horsepower and won’t do as much damage as an elite athlete. Share on XIntensity relates to the velocity achieved during sprints. Maximal velocity typically means anything over 90% of an athlete’s fastest time. It has been said many times, but in most cases, to get fast you have to train fast. That comes with increased risks—especially if the athlete is not prepared. Where the art of coaching comes in is how you manipulate each variable. Developing constraints or intensity limiters are a great way to program sprint training. You can do this by utilizing:

- Timed sprints (record performance drop-offs)

- Build up sprints

- Resisted or hill sprints

- Yardage limiters (athlete is asked to do a 40 yard-sprint and is told that the 20‑yard mark is where they can no longer accelerate past; whatever speed they built up to in that initial 20 yards is what they maintain for the second 20 yards)

- Play with complete and incomplete recoveries (rest intervals)

The key here is to slow cook progress and to not overlook technique. Running fast is much more than force production and rate of contraction-relaxation.

One other form of short-long that many of us coaches use is during ground contact times for plyometrics. Shorter ground contact times are found in movements like sprinting, depth jumps, hurdle hops, jumping rope, and other forms of extensive hopping. Longer ground contacts can be found during weighted jumps, broad jumps, and any jumps that aim to generate force over a longer time scale. Both are very important when it comes to training for general athleticism. A big push in the strength and conditioning field is using data to quantify if an athlete is force dominant or velocity dominant. Depending on what you find, training can then be specific to the needs of that athlete.

A coach that does a great job at this is Aaron Wellman. Aaron has found a way to seamlessly introduce data collection into his training sessions. Each athlete might be doing a jump exercise, but the emphasis area will differ for each group. One group might be doing a hurdle hop with jump mats. Another group might be doing weighted box jumps. This is just a small example of using short-long ground contacts within a session.

Stiffness-Compliance

The emergence of tendon research has brought this next form of contrast front and center: stiffness and compliance. I think a well-rounded approach to training muscles and tendons will serve your athletes better than simply focusing on one. Commonly, in a tendon-muscle relationship, there is both stiffness and compliance. Where the muscle meets the tendon, there must be some pliability there; where the tendon meets the bone calls for more stiffness. How these are trained will differ a bit.

If we have strong muscles but not enough tendon integrity, we can see injuries in these connective tissues. For increased stiffness, think dynamic movement. Dynamic in the form of sprinting, jumping, cutting, etc. This fast coupling is what builds cross links in the tendon, making it stiffer. As it turns out, inactivity also increases stiffness, but not in a positive way. Keith Baar has shown that tendons don’t need much more than 10 minutes of loading to see benefits.

If we have strong muscles but not enough tendon integrity, we can see injuries in these connective tissues. Share on XThis has interesting implications in the return-to-play world. From what I’ve gathered, it also seems that female athletes may be predisposed to tendon/ligament injuries because of an interaction with hormones and the development of cross links within connective tissues.

Compliance is another, equally important aspect of tendon-muscle training. If we make a tendon stiffer than a muscle is strong, muscle pulls can happen. An example of this might be observed during mini-camps in the NFL. Players are primarily doing fast, dynamic movements that increase stiffness. The weight room is often one of the first things to go. Without slower strength work, the muscle-tendon junction may be vulnerable to soft tissue pulls. The general recommendation to balance out stiffness with compliance is slow movements.

Heavy weight training can be applied as one means. Another is the use of isometrics. Holding an isometric for 30-40 seconds can be enough loading in the tendon to break cross links and build compliance. Again, Keith Baar is an excellent resource on all things tendons. A good rule of thumb for coaches is:

- First, prepare the athlete’s tendons and tissues to match what they will experience in their sport.

- Next, give the athletes what they aren’t getting in their sport.

If they are basketball players and are jumping all the time, plug in exercises for tendon health and compliance. A balance of the two seems to be a good starting point.

Lifestyle

It is often said that in life we need to find balance. While that holds true for a majority of situations, there are however some instances where contrast plays itself out in our lives.

The first example of that is in the contrast between sleeping states and states of wakefulness. Sleep and its importance in performance and health has been a big topic of conversation over the past few years. Matthew Walker has done a wonderful job of laying out actionable information for the layperson. Sleep is a vital aspect of our lives and, if possible, shouldn’t be compromised.

Sleep is a vital aspect of our lives and, if possible, shouldn’t be compromised. Share on XOn the other side of sleep—and an area that offers an interesting point—is the state of wakefulness. Wakefulness is exactly as it sounds. How we spend our day, more specifically our early and late hours, will either support or hinder the quality of sleep we receive each night. Our bodies are programmed to follow a certain cycle or rhythm. The basic term that represents this cycle or clock is called the “circadian rhythm.” This clock dictates specific functions and actions of our bodies that are important.

As we wake up, we need natural light exposure in our eyes. This light exposure helps initiate our clock and sets the stage for sleepiness to occur some 12-16 hours later. Without adequate light exposure we experience a delay or lag in wakefulness. We also need some natural light exposure in the early evening hours. Seeing the sun at a low position in the sky is useful for the body and its preparation for sleep.

It is important to get light in both the early and later parts of the day. A common recommendation is to get 10-15 minutes of exposure at both times. Depending on how much light is available in your area, that threshold will expand out to get sufficient lux.

Another way we can “hack” the body’s current state is through breathing. Breathing is another vital part of life and is something that has a massive impact on our quality of life. It seems that a more optimal form of breathing should be more or less reflexive and heavily involve the diaphragm. Breath is a way to use our physiology to shift into what is required of us in that specific context.

How we cadence and perform each breath can place us into a more sympathetic- or parasympathetic-dominant state. Generally speaking, sympathetic is our body’s “fight or flight” mode and parasympathetic is more of our “rest and digest” mode. Both are very important.

If we want to heighten our arousal levels, focusing on the inhalation portion of each breath will help us achieve this. A popular technique known as the Wim Hof method, uses a fast cadence in order to hyperoxygenate our bodies. This leads to a more “alive” feeling.

We can also use breath to down-regulate ourselves, which is very much needed in the high-stress environments that we all face in today’s society. To shift ourselves into a more parasympathetic state, our focus then slides to the side of exhalation. By extending and slowing down the rate at which we exhale, we tend to offload more carbon dioxide.

We can also use breath to down-regulate ourselves, which is very much needed in the high-stress environments that we all face in today’s society. Share on XStanford neuroscientist Andrew Huberman explained a specific action for dampening the stress response known as the physiological sigh. A physiological sigh is a pattern of breathing in which two inhales through the nose are followed by an extended exhale through the mouth. Huberman explained that the double inhale portion of the physiological sigh pops the air sacks (called alveoli) open, allowing oxygen in and enabling you to offload carbon dioxide in the long-exhaled sigh out. These are just a few examples of how contrasting our breath can alter our current status.

Finding Contrast In Your Life

Contrast exists in most dimensions of life. Without it, we have little context for comparison in our perceptual field. Our goal as coaches is to leverage contrast and use it most effectively with our athletes. These are only a few examples. I challenge you to find more within your programs and develop a fundamental understanding of how to apply them.

“The greater the contrast, the greater the potential. Great energy only comes from a correspondingly great tension of opposites.” – Carl Jung

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF