Although it can be argued that running speed is the No. 1 component of athletic fitness, jumping ability rules in many sports. You don’t have many basketball, volleyball, or gymnastic coaches testing their athletes in the 40, yet there is cause for concern when these athletes unexpectedly lose 2 inches on their vertical jump. Besides assessing leaping ability, vertical jump test results can provide valuable insight into how to design better workouts. There’s a lot to unpack here.

“The vertical jump tells you how quickly an athlete can start a movement and apply force,” says sports scientist Jonathan Wahl, Ph.D. “It’s equivalent to that first step in tennis, that explosion off the line of scrimmage, and that leap out of the starting blocks.” In one 2015 study, researchers said jump tests “may be used by coaches for assessing and monitoring qualities related to sprinting performance in elite sprinters.”

My premise is that to design the best workouts for a specific sport, you should consider using multiple jump tests. Share on XMy premise is that to design the best workouts for a specific sport, you should consider using multiple jump tests. For example, you could make the case that the standing broad jump would be more specific to the start of a sprint, and the vertical jump would be more specific to the upright sprint position. Further, I’ve talked to sprint coaches who believe that a single-leg triple jump is a better test for assessing maximal acceleration than a standing broad jump.

With that sales pitch, let me show you how I’ve refined vertical jump testing over the past two decades to make it more sport specific. Let’s start by reviewing a bit of history on jump testing technology.

The Evolution of Jump Testing

In 1921, Dr. Dudley Sargent developed the Sargent Jump Test. It involves chalking the fingers of one hand and standing next to a wall. Without taking a step, you jump as high as possible and touch the wall at your highest point. The difference between your standing reach and your jump height is your vertical jump.

The next major evolution of this test is to hit a series of moveable plastic tabs, set a half inch apart and mounted on an adjustable pole; the more tabs you hit, the higher your score. This device is called a Vertec, and it is still used in the NFL Combine (image 2).

The Vertec was a dramatic improvement over the wall-and-chalk method, but one problem with both these tests is that it’s possible to cheat. Cheating is not an issue with how high you jumped (although with homemade and knockoff versions of the Vertec, I saw that athletes could often hit an extra tab by slapping it hard and upward). The problem is the starting measurement for the reach. Retracting your shoulders, leaning back, and slightly unlocking your knees can reduce your standing reach by several inches, thus giving you a higher score.

The contact mat, which involves a rubber mat containing sensors attached to a handheld computer (image 2), was the next “step” in vertical jump training. The athlete stands on the mat and jumps; how long they spend in the air determines their vertical jump.

Unlike the Vertec, a contact mat provides smaller jump increments. Instead of measurements such as 20 inches and then 20.5 inches, you can have 20, 20.1, 20.2, and so on. Because kicking your heels up as you jump could increase flight time, coaches should watch for this technique to maintain consistency among their athletes.

The athlete also doesn’t have to strike anything with a contact mat. This means you can perform a jump with your hands down to determine leg power more precisely (because the upper body assists in jumping). You can also measure upper body power (with a plyometric push-up) and use it as an electronic timing system for sprints and shuttle runs, and the one I used could measure multiple jumps.

Because an entry-level contact mat costs about the same as a Vertec and is more versatile, I’ll focus on testing with this device for the remainder of this discussion.

Fine-Tuning Jump Testing

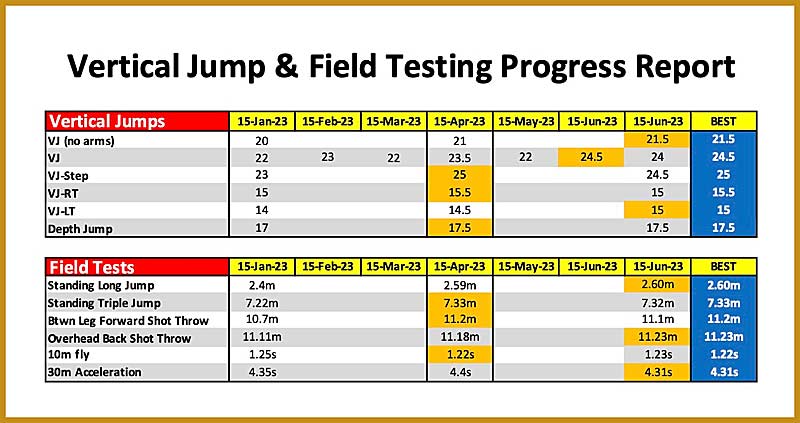

As a starting point for personalizing your jump testing program, consider the sample testing form in image 3. The vertical jumps are ones I’ve been using for more than two decades, and the field tests are the ones used by Gabriel Mvumvure when he was a sprint coach at Brown University. Together, they provide an extensive assessment of athletic fitness for a sprinter.

Note that all the vertical tests were not performed monthly to save time. Rather, the vertical jump with arms is performed more frequently to give a general estimate of progress and determine if additional tests need to be performed. One of the problems with testing too frequently is that it can consume 1–2 days of practice time, and athletes often slack off on their training during the days before the test to score better.

One of the problems with testing too frequently is that it can consume 1–2 days of practice time, and athletes often slack off on their training during the days before the test to score better. Share on XI organized the tests in this order for consistency. However, if a multiple jump test is included, it should be performed last because the fatigue it creates could influence the results of the other tests.

Let’s take a closer look at these vertical jump tests, along with some tips on improving their results:

1. Vertical Jump (No Arms)

Description: A standing vertical jump without the assistance of the arms

Athletic Quality: Leg power

Discussion: In many sports, such as hockey, the legs produce power without the arms extending over the head. Because it’s tempting to cheat with the arms at your sides, I have athletes perform this jump with their hands on their hips.

You can also use this test to measure an athlete’s strength deficit, providing insight into whether an athlete needs to focus on strength or explosiveness. I’ve read Eastern Bloc textbooks that use medicine balls of various weights to measure the strength deficit. If there is little difference among the distances the med balls are thrown, an athlete may need to work on explosiveness, such as with plyometrics. It can also suggest that an athlete is overtrained, so modifications must be made to the volume and intensity of their workouts. I saw a dramatic example of the need for such testing when I took Dr. Don Chu’s weight training class at California State University in the early ’80s.

Chu had three athletes perform a chest pass with a 16-pound medicine ball for distance. Two athletes were football players, and I recall one could bench press 380 pounds and the other 400. The other athlete was a javelin thrower who went on to make the Olympic team, weighed about 165, and allegedly only visited the weight room when he was looking for someone. The result?

The football player who benched 400 tossed the med ball 32 feet, and the other tossed it 28 feet. The javelin thrower tossed it 42 feet before it hit the wall! Even though this test was similar to a bench press motion, the football players’ relatively slow strength training methods didn’t develop the explosiveness that the javelin thrower’s training did.

As for jump training research on lower body explosiveness, one study compared the vertical jumps of powerlifters and weightlifters using body weight and an additional 44 pounds and 88 pounds of resistance. The researchers found that the weightlifters performed better in all three tests. Even though the powerlifters can usually squat more than the weightlifters, their training does not transfer as well to dynamic movements.

Although a weight vest can be used to test the strength deficit, the jump can be performed with a barbell on the shoulders (image 4). This method enables you to quickly and precisely add additional resistance, such as one-eighth of body weight and one-quarter of body weight. A hex bar can also be used (image 4). Athletes may find a hex bar more comfortable; however, the jumps may be higher because the traps are more involved.

2. Vertical Jump

Description: A standing vertical jump using the arms

Discussion: Using your upper body increases vertical jump height, which supports the idea that some upper-body training may be necessary to achieve maximum results in the vertical jump.

With sprinting and plyometrics, asking heavily muscled or overweight athletes to perform high-intensity/high-volume sprint or plyometric workouts is asking for injury. Box jumps are a safer alternative, where athletes jump onto a box and step (not jump) down. They are still performing an explosive concentric contraction, but there is minimal stress as their landing is only a few inches. Video 1 shows a conventional box jump and a weight-release box jump that provides a form of contrast training (post-tetanic potentiation).

What types of plyo boxes are best?

Solid boxes are better than open metal boxes because an athlete’s feet can easily get caught in an open plyometric box. With a solid box, an athlete’s feet slide down if they don’t jump high enough. The metal boxes tend to be cheaper, but the risk of injury may not be worth the savings.

A pyramid shape is more stable than a rectangular design (image 5), and a non-slip surface on the top makes it even better (although it increases the price). Also, with some plyometric boxes, a “booster” can add a few inches of height. Rather than purchasing higher boxes or boosters, some coaches will place thick bumper plates on top of plyo boxes, which should be considered a new level of stupid. This dangerous practice puts the athlete at a high risk of a horrific injury—Google “box jump fail” if you doubt me.

Sturdy foam boxes with a cloth covering are the best option (video 1), and many have Velcro to enable them to be securely stacked. Foam boxes are solid, and there is little risk of scraping your shins on the edges of these boxes (and I’ve seen some ugly scrapes in my day—one so bad that the bone was exposed!). The downside is that they are about twice the cost of wood boxes. However, the stacking feature reduces costs because they can be combined to create different heights.

Video 1: Foam boxes prevent scraping the shins and can be stacked securely. A conventional box jump (note the athlete steps down) and a weight-release box jump are demonstrated.

Next, there is weightlifting, and the jumping abilities of throwers and weightlifters testify to the value of these exercises for increasing leaping ability. I prefer the full lifts over the power versions, but both will increase the vertical jump and are less stressful for heavier athletes than many forms of jumping or plyometric training.

Because jerks are a more complex movement, another option is the push jerk, which can be performed by removing the barbell from squat racks (video 2). These movements work the ankle differently than cleans and power cleans, so I encourage athletes to perform some overhead work for more complete development. Because many sprint and jump coaches are reluctant to have athletes squat or perform any lifts from the floor during the season, push jerks are a good alternative because they produce less lower-body fatigue.

I must emphasize that push jerks (and jerks) are not upper-body strength exercises such as the military or bench press but dynamic lower-body movements involving a plyometric component. Share on XI must emphasize that push jerks (and jerks) are not upper-body strength exercises such as the military or bench press but dynamic lower-body movements involving a plyometric component. Case in point: When I was 17 and weighed about 180, I jerked 335 pounds overhead but missed a 205-pound bench press in that same workout.

Video 2: Push jerks are an effective weight room exercise for increasing vertical jumping ability. The bar can be removed from squat racks or cleaned first.

3. Vertical Jump-Step

Description: A vertical jump using a one-step approach

Athletic Quality: Elastic properties of the lower extremities, particularly the soleus (lower calf muscle)

Discussion: This test involves taking one step and then jumping.

German sports scientist Dietmar Schmidtbleicher is one of the foremost experts on plyometric training. He says there are two basic types of jumping actions, which he refers to as stretch-shortening cycles. “Two types of stretch-shortening cycles exist, a long and a short one. A long SSC (e.g., jump to throw in basketball, jump to block in volleyball) is characterized by large angular displacements in the hip, knee, and ankle joints and a duration of more than 250ms. A short SSC (e.g., ground contact phases in sprinting, high jump or long jump) shows only small angular displacements in the above cited joints and last 100–250ms.”

This difference in stretch-shortening cycles was apparent in my work with figure skaters. As with high jumpers, figure skaters transfer horizontal speed to the vertical with a short stretch-shortening cycle. When only two females had landed a clean triple axel jump in competition, I tested the vertical jump of a Chicago female skater who did a triple axle in a practice session at the Olympic Trials. Her best vertical jump with a step: 18 inches!

Additional options to train this athletic quality include box jumps with one or multiple steps and, of course, bounding exercises. Chu’s classic book, Jumping into Plyometrics, demonstrates many jump variations. As shown in image 6, narrow foam barriers can be easily stacked, decreasing the risk of injury.

4. VJ-RT and VJ-LT

Description: A single-leg vertical jump

Athletic Quality: Determines muscle imbalances and foot arch function

Discussion: Muscle imbalances are considered a risk factor for injuries. There has been considerable interest in looking at strength ratios of the quadriceps and hamstrings using leg extension/leg curl machines. Sports scientists later expanded on this idea to include muscle imbalances between each leg. Let’s look at an example of how vertical jump testing can be used to assess imbalances.

With figure skating and the hurdles, the landing leg is often stronger than the takeoff leg because of the higher eccentric stress. In his senior year in high school, hurdler Bretram Rogers suffered a severe hamstring injury that he elected not to have surgically repaired but required many months of rehab. To avoid muscle imbalances, particularly for a hurdler with such an injury history, I included a lot of unilateral exercises in his workouts, and Coach Mvumvure addressed this issue in his sprint workouts. In his senior year at Brown University, after the indoor season, he jumped 24 inches on his right leg and 24.5 inches on his left. During the outdoor season, Rogers broke the 62-year-old outdoor record in the 110m hurdles.

I’ve also found that deficiencies in single-leg jumping ability are often caused by weakness in the muscles that extend (plantar flex) the foot and the muscles of the feet. I say this because by using postural insoles that stimulate the nerves in the feet to reform the arch, I’ve seen as much as 2 inches of improvement in single-leg vertical jumping and up to 3 inches in double-leg jumping in about 15 minutes with male athletes. (FYI: For a better assessment of arch function, I often have athletes perform single-leg vertical jump tests barefoot. Shoes often provide support that gives a false assessment of the postures of the arch.)

To better assess arch function, I often have athletes perform single-leg vertical jump tests barefoot. Shoes often provide support that gives a false assessment of the postures of the arch. Share on XAs for corrective exercises, using a mini-trampoline can be valuable for improving the function of the ankle during dynamic movements. Paul Gagné developed one series of box jump exercises using a mini-trampoline, which can also be performed barefoot (video 3). Says Gagné, “Yes, sports are played on a flat surface, but the elastic qualities of the mini-trampoline help improve the timing of the ankle and foot during dynamic movements, thus helping to avoid injury and improve athletic performance.”

Video 3: Single-leg trampoline jumps to a box help develop body awareness and timing to improve performance and prevent injuries.

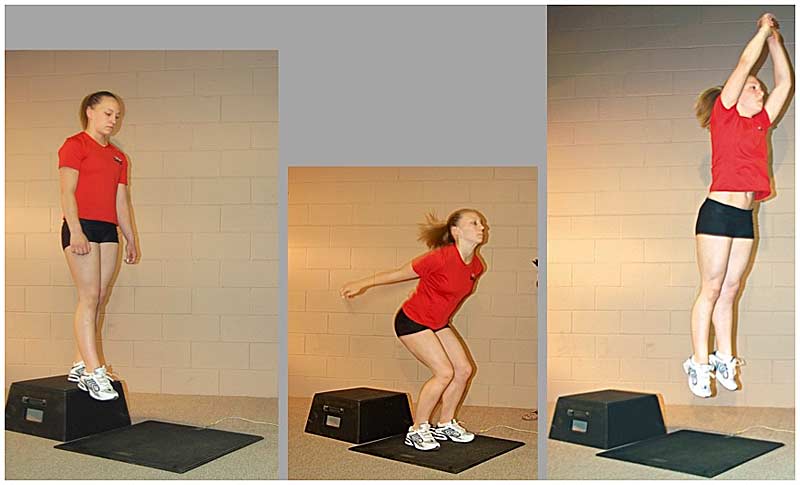

5. Depth Jump

Description: Jumps performed off a platform

Athletic Quality: Fast eccentric strength

Discussion: Depth jumps are often used to develop the fast eccentric strength necessary to change directions in sports. Although some coaches have set specific heights using variables such as age and training experience, it’s better to be as specific as possible.

The depth jump test shows at what height jumping results decrease to help determine what height platforms you should use for depth jumps, which are high-intensity exercises (images 7a, 7b, and 7c). Thus, if your max depth jump height is 15 inches, you should keep your depth jumps to 15 inches or less in practice. Using a platform that is too high reduces the plyometric training effect because the athlete will spend too much time on the floor, dissipating much of the stored energy. (An analogy is downhill running. If your hill is too steep, you will expend too much energy braking.)

I once tested the vertical jumps of female gymnasts at an elite training club and found that many of these athletes were jumping higher without a step. This could be due to the lack of progressive overload in eccentric contractions, so exercises such as depth jumps could be useful in improving this athletic quality.

For example, I trained a 15-year-old gymnast who could vertical jump 22 inches with and without a step. After two months, she still had identical results in the vertical jump both without and with a step but was up to 24.6 inches. Because she was training 25+ hours a week, I could only add two 15-minute jump training sessions per week, and many weeks she could not handle any additional jump training due to a demanding competition schedule. Six months later, she jumped 26.5 without a step and 27.5 with a step. Had she not been practicing gymnastics, my guess is that there would have been a greater difference in the two measurements.

Bonus Test #6. Lewis Formula

Description: Vertical jump and bodyweight formula

Athletic Quality: Power

Discussion: While sprinting speed is coveted in many sports, body weight must also be considered when assessing an athlete’s power. Case in point: New England Patriots running back Rhamondre Stevenson.

Stevenson participated in the 2021 NFL Combine, where the best 40 times for a running back was 4.38. Stevenson covered the distance in 4.64, ranking him 31st in that position. Nevertheless, he was considered one of the League’s best last year, with 1,040 rushing yards and 431 receiving yards. The difference is that Stevenson weighed 231 pounds.

Stevenson is better built to plow through an offensive line and break tackles than, say, a 185-pound running back who runs the 40 in 4.50. (FYI: The running back who ran 4.38 in that NFL Combine weighed 175 pounds. Although an accomplished college athlete, he spent most of his NFL rookie year on the practice squad and was waived the following year.)

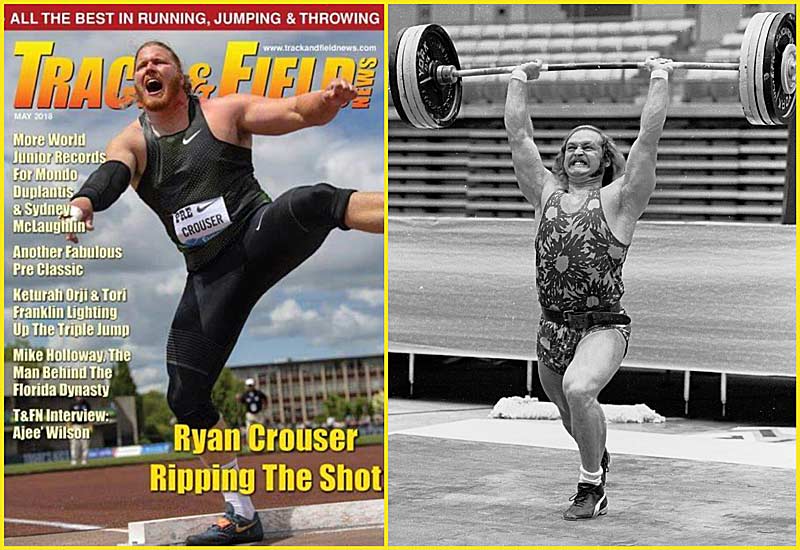

The point is that besides sprinting speed, coaches should consider an athlete’s power. Power can be assessed with the Lewis formula (see my article on athletic fitness testing). The Lewis formula determines power with a formula that combines an athlete’s body weight and vertical jump. Stevenson had a 31.5-inch vertical jump, making him an especially powerful athlete. The Lewis formula would also be valuable for shot putters and discus throwers.

In the shot put, Ryan Crouser holds the current world record at 76.8 1/4 feet/23.38m (image 13). He weighs 319 pounds and has a 34-inch vertical. In 1988, Ulf Timmermann broke the world record with 75.6. At 262, he had a 36-inch vertical. In the early ’80s, when I lived in California, I trained at the Iron Works Gym in San Jose and worked at the San Jose YMCA. Among those accomplished throwers I often saw were Al Feuerbach (image 8b), Brian Oldfield, Mac Wilkins, Art Burns, and Richard Marks. These men are the athletic embodiment of power.

Additional tests many of these contact mats can provide are 60 jumps to measure muscular fatigue and four consecutive jumps to measure reactive ability. In the four-jump mode, the athlete jumps four times as quickly and as high as possible. The software will determine the average ground contact time and average jump height. This data has a specific application to basketball.

Chu said that in basketball, particularly women’s basketball, it’s often not the person who jumps highest who gets the rebound but those who can jump higher on the second, third, or fourth attempt to grasp the ball. As a result, Chu developed a specific jumping drill with a medicine ball to emphasize this athletic quality. (FYI: Chu was the strength coach for the Golden State Warriors for several years.)

As a matter of full disclosure, the 60-jump test is one I’ve never used. Instead, I did a double-leg 12- and 16-inch lateral box jump test for 90 seconds (which I learned from Chu). I found this test correlated well with the anaerobic endurance test used at the Air Force Academy with its football players. Their test involved three consecutive quarter-mile runs with a 60-second rest between reps.

Rise of the Force Plate

Technology has provided us with many exciting new methods of testing vertical jumps, including force plates that assess how you jump and fiber optic techniques that determine how you land. The data collected from these tests is believed to help determine an athlete’s risk of specific injuries, including those to the upper body. One system analyzes the forces produced by breaking down the three phases of a vertical jump (eccentric, isometric, and concentric).

Technology has provided us with many exciting new methods of testing vertical jumps, including force plates that assess how you jump and fiber optic techniques that determine how you land. Share on XBrandon O’Neall is the head strength coach at Brown University. O’Neall has been an advocate of using the latest technology to enhance performance, incorporating velocity-based training systems with Brown athletes since he took the top position in 2011. Brown University recently acquired one of these sophisticated force plate systems, and it will be interesting to see what his data tells us.

Getting back to the present, there may be other jump tests you like that I didn’t mention, and certainly, there are many other athletic fitness training methods to improve jumping ability than the ones I’ve discussed. The takeaway is that by fine-tuning their vertical jump testing program to make it more sports-specific, a coach can better assess the physical preparedness of their athletes. From here, they can reevaluate their training methods to help athletes overcome weaknesses and achieve the “highest” levels of athletic performance.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Goss, K. “The Case Against Stability Training.” Bigger Faster Stronger, March/April 2007.

Loturco I, et al. “Relationship Between Sprint Ability and Loaded/Unloaded Jump Tests in Elite Sprinters.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. March 2015;29(3):758–764.

Hackett D, Davies T, Soomro N, and Halaki M. “Olympic weightlifting training improves vertical jump height in sportspeople: a systemic review with meta-analysis.” British Journal of Sports Medicine. July 2016;50(14):865–872.

Schmidtbleicher D. “Training for Power Events.” Strength and Power in Sport, 1992. pp: 381–395.

Chu, D. Jumping into Plyometrics, 2nd Edition, August 1, 1988. Human Kinetics.

Gagné, P. Personal Communication, February 2023.

Track and Field All-Time Performances Homepage, alltime-athletics.com.

Stone, Michael and O’Bryant, Harold. Weight Training: A Scientific Approach, Burgess International Group, Inc. 1984 pp. 166–168.

Should I try to measure a maximum vertical jump or a maximum box jump or just measure both?