Almost 10 years ago, I wrote an article for this website highlighting some research on the role sleep plays in elite performance. The article was hugely popular at the time and is still frequently shared on social media, suggesting that the topic of sleep—particularly the role it plays in performance—is of interest to many in the sporting sphere. Sleep has also captured the interest of many researchers in the field of sport, meaning that our knowledge in the area is accelerating rapidly.

Given this interest—and the amount of new research since that original article was published—a close look at what we now know about the connection between sleep and elite athletes is well worth a close look. Updating our knowledge in an area is always important, especially when we consider that over 80% of all peer-reviewed research on the topic of sleep and athlete performance comes from 2011 onwards.

Why Do We Sleep?

Sleep is essential for both the brain and body, with research highlighting that even just one to two weeks of partial sleep restriction:

- Impairs cognition and our ability to learn and form memories.

- Harms mental health.

- Disrupts cellular growth and recovery.

- Changes our metabolism.

- Weakens our immune system.

Sleep is a normal part of the typical human 24-hour day-night cycle, in which a period of alertness and wakefulness is followed by sleep, a period of recovery. Normal human sleep has two main types: non-rapid eye movement sleep (non-REM), and rapid eye movement sleep (REM). Non-REM has three progressive stages: stage 1 and 2, which are termed light sleep, and stage 3, which is termed deep (or slow wave) sleep. During non-REM sleep, the brain is mostly inactive, while it is highly active during REM sleep; the vast majority of dreams occur during REM sleep. In young adults, around 60% of all sleep is light sleep, 15% is deep sleep, and 25% Is REM sleep.

When we sleep, a number of hormones are released, including growth hormone. This hormone is crucial for the repair and growth of the body’s tissue—of particular interest to athletes are its beneficial effects on muscle growth, repair, and bone building. Around 95% of the daily production of growth hormone occurs during stage 3 sleep, highlighting the importance of sleep for adequate growth and repair. Other important hormones related to sports performance, such as cortisol and testosterone, follow a circadian rhythm. As such, their release can be disrupted by sleep deprivation.

While it is generally considered that there are no serious consequences from moderate sleep loss—defined as around 6 hours sleep per night—over reasonably prolonged periods, there is evidence that chronic, sustained sleep loss (around 4-6 hours per night) does have long-term health implications. Individuals who habitually sleep for around 5 hours per night tend to have an increased risk of type-II diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease, along with an increase in overall mortality.

There is evidence that chronic, sustained sleep loss (around 4-6 hours per night) does have long-term health implications, says @craig100m. Share on XThe true reason(s) as to why animals sleep is currently unknown and hotly debated. There are several theories, which include sleep having an overall restorative effect on the body, allowing it to recover and repair following the waking state, as well as a clear cognitive component with sleep having a vital role in learning and memory consolidation. Whatever the true reasons for humans needing to sleep—and it’s unlikely there is just one—it’s clearly something that is important for all of us to do, and do properly. And yet, we don’t; the average total sleep duration of adult humans has steadily decreased, from around 9 hours per night in the 1950s, to just over 7 hours in the 1980s. A 2013 survey in the US reported an average sleep of 6 hours 51 minutes on workdays, despite respondents reporting, on average, that a total sleep time of 7 hours 17 minutes was required for them to operate optimally the next day. If the normal population of people have such poor sleep, what does it look like in athletes?

Sleep and Elite Athletes

Perhaps the best paper on sleep in elite athletes comes from 2017 from a group of researchers in the UK led by Luke Gupta. In their paper, the authors had two aims:

- To understand the patterns and quality of sleep in elite athletes.

- To understand what may harm sleep in elite athletes.

In total, they found 37 studies that met their inclusion criteria, comprising athletes from Olympic, Paralympic, and team sports. Overall, the results suggest that elite athletes typically have a lower sleep efficiency, spend more time in bed, experience greater sleep fragmentation, and take longer to fall asleep than non-athletes. When comparing between sports, individual athletes tend to have poorer sleep quality than team sport athletes.

Elite athletes also tend to experience sleep disturbances, with ranges of 13-70% reported in studies. There is some research that suggests sleep disturbances are more common in female athletes. One way of measuring sleep quality is the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), a validated survey. Research using the PSQI suggests that as many as 60% of athletes report disordered sleep and up to 26% of athletes experience highly disturbed sleep. As part of a large-scale project driven by the Australian Institute of Sport, researchers examined various markers of performance health in athletes prior to the 2016 Rio Olympic Games. There were strong relationships between increased levels of stress and poor sleep—defined as lower sleep quality, increased sleep disturbances, or increased time to fall asleep. In addition, in the same group of athletes, over 50% scored above 5 on the PSQI, which is indicative of poor sleep.

There were strong relationships between increased levels of stress and poor sleep, says @craig100m. Share on XThese findings are potentially worrying for a number of reasons. As outlined above, sleep appears to somewhat regulate the release of a variety of hormones important for recovery. In addition, there is a growing body of research which suggests that disturbed sleep is associated with poorer mental health outcomes in athletes, as well as burnout and mood disturbances. A lack of sleep also appears to negatively affect cognitive function; REM sleep is crucial for developing memories and learning motor skills, and so a reduction in this type of sleep will harm learning. A 2014 review, published in Sports Medicine, highlights the effects of sleep loss on exercise performance, as well as the response to exercise. The results make for sobering reading. Reductions in sleep appear to harm exercise performance—especially aerobic exercise—and increase the post-exercise inflammatory response, meaning recovery time will increase.

Sleep and Youth Athletes

Clearly, elite athletes need to ensure they get sufficient sleep—and many of them don’t—but about youth athletes? A 2020 paper from Current Sports Medicine Reports provides a thorough review on how sleep affects performance in youth athletes, and it makes for interesting reading.

Sleep for youth athletes can be a challenge due to the various competing demands on their time. Youth athletes typically spend 6-8 hours per day at school (including travel to/from and extra-curricular activities), along with homework, spending time with friends, training, and, in some cases, undertaking part-time employment. This leaves little time in the day for sufficient sleep; and, often, youth athletes will prioritise other activities at the expense of sleep. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends that teenagers aged 13-18 get 8-10 hours of sleep regularly; we know from at least one study that many youth athletes get less than 8 hours of sleep per night. For example, this study on youth gymnasts found that over 91% slept for less than 8 hours per night. In this study, a group of adolescent athletes consistently got less than 8 hours sleep per night; in another, 40% of collegiate athletes regularly sleep for less than 7 hours per night during the week; and, finally, athletes from state netball teams in Australia regularly achieved less than 8 hours sleep per night.

It’s worth pointing out, however, that this isn’t just a problem that affects young athletes; it affects youngsters regardless of whether they’re an athlete or not. This was highlighted in a 2019 paper, which compared 625 adolescent elite athletes to 391 adolescent non-athletes. The authors found that the athletes slept for longer than non-athletes, but that both groups fell short of the up to 10 hours recommended sleep. This can have further implications, as evidenced by a 2018 study on elite Gaelic athletes. Here, the authors found that “poor sleepers,” as quantified by the PSQI—a validated sleep assessment tool—had significantly lower general health, increased stress, and increased confusion when compared to athletes who were classified as good sleepers. This connection with wellbeing has been reported elsewhere; for example, in a group of youth athletes, daily reported wellbeing scores were correlated with sleep duration, a finding that has been replicated. This highlights that the very perception that they have not slept well means they typically feel worse the next day, which can harm their performance and wellbeing.

“Poor sleepers,” as quantified by the PSQI, had significantly lower general health, increased stress, and increased confusion when compared to athletes who were classified as good sleepers, says @craig100m. Share on XEven getting enough sleep—in terms of hours—may not be enough for youth athletes. In a study on Dutch elite youth athletes, the researchers reported that 41% of the athlete cohort were classified as “poor sleepers” on the Global Sleep Quality Score, despite the average sleep duration time being above 8 hours. This holistic score includes aspects such as sleep quality (how deep is your sleep), sleep latency (how long it takes you to fall asleep), sleep disturbances, sleep medication use, and daytime dysfunction.

This all has an impact on the performance of youth athletes. For example, in the study on Australian netballers mentioned earlier, the best two teams in the competition achieved an average of just over 8 hours of sleep per night, while the worst two averaged just over 7. In addition, there is an increasing amount of evidence highlighting the role that a lack of sleep plays in increasing the risk of injury. In a study from 2014, the authors found that school-aged athletes who slept for less than 8 hours per night were 1.7 times more likely to have experienced an injury than those who slept for more than 8 hours. As such, it’s clear that a lack of sleep is common in high level youth athletes, and with this lack of sleep comes a whole host of problems.

Why Don’t Athletes Get Enough Sleep?

Returning to the study from Gupta and colleagues mentioned earlier, the second part of the paper aimed to explore some of the reasons elite athletes may have poor sleep. They identified three key risk factors for why athletes may have poor sleep:

- Competition—Research highlights that a number of athletes report poor sleep the night before a competition, although this is somewhat inconsistent. In research where sleep quality is determined via questionnaire (i.e., the athletes self-report), typically athletes have poorer sleep immediately before competition, and there is some evidence that this effect is greater in higher standard athletes. However, when sleep is measured by objective measures—most commonly wrist actigraphs—there appears to be no difference in sleep efficiency or sleep onset latency before a competition when compared to normal training. In fact, using this method, there is some research that reports increases in sleep time and sleep efficiency in athlete pre-competition (i.e., they slept better).

- This suggests that athletes may perceive they sleep worse prior to competition—perhaps due to stress—but actually there may not be any differences. There is less inconsistency in the results of studies exploring sleep post-competition; here the research is clear that athletes tend to have less total sleep and a significantly delayed bedtime (the two likely being linked). This suggests that competitions, likely because of the late start and use of stimulants such as caffeine, may harm sleep quality post-event—an important consideration when it comes to planning recovery techniques. There is some evidence that increases in cortisol, as a result of the stress of competition, also harm sleep. Specifically in track and field, there is evidence that, as they get closer to competition, elite athletes have worse sleep.

- Travel—Having to travel for competitions or training camps is a common occurrence for elite athletes. Travel itself appears to have no impact on sleep (aside from early-morning or late-night travel), but the jet lag associated with travel across time zones can negatively affect the time taken to fall asleep, as well as the time spent asleep.

- Training—The research suggests that athletes wake earlier, and, as a result, sleep less on days that they’re training. There is a consistent and strong relationship between training start time and total sleep time, such that the earlier training starts, the less athletes sleep. I know this sounds obvious, but it highlights that athletes don’t typically go to bed earlier when they have morning training, they just sleep less—meaning, it’s something coaches must keep in mind when scheduling training. The intensity of training also appears to affect sleep, with more intense training periods associated with a decrease in sleep efficiency and an increase in time taken to fall asleep.

Another potential reason why athletes don’t get enough sleep is their regular use of caffeine. Caffeine is a common and well utilized ergogenic aid, with clear performance enhancing effects; a review I was part of back in 2020 highlighted the consistent beneficial effect of caffeine on performance. Caffeine also harms sleep quality and duration, as highlighted in a 2017 review. These effects were present at surprisingly low doses of caffeine; for example, consuming 1-2 double espressos (~200mg caffeine, the same as most pre-workout formulas) sixteen hours before sleep had a negative effect on the sleep quality. Because athletes regularly use caffeine, they are therefore likely to suffer some sleep disturbances as a result.

Because athletes regularly use caffeine, they are therefore likely to suffer some sleep disturbances as a result, says @craig100m. Share on XThis effect is increased post-competition, especially if the competition is in the evening. As a moderate caffeine user during my competitive days, I regularly would not sleep, or only get to sleep for a couple of hours, the night after a competition. This effect is not limited just to me; a 2018 study in elite rugby union players reported an average of 1.5 hours less sleep the night after a game (with bedtime being 3.5 hours later), which was linked to the use of caffeine by these players. The authors found that increases in caffeine concentration in the saliva of the players was associated with an increased time to fall asleep, a reduction in sleep efficiency, and less sleep overall.

The environment in which we sleep is crucial in setting the foundations for optimal sleep. Ideally, we need it to be cool, dark, and quiet. Getting it wrong can have significant implications. For example, in a study of collegiate athletes based in the US, 42% of athletes had poorer sleep quality on campus—their primary place of residence—than when travelling for sport. These various drivers of poor sleep in athletes are good to know—but what can we do about them?

Sleep-Based Strategies to Support Performance

Given that we know sleep quality and duration are important, and we know that elite athletes don’t always get enough sleep (or enough high quality sleep), an obvious question is: “How can we improve this?” Fortunately, that’s the topic of this review article published in 2018; here, the researchers explored a variety of sleep interventions designed to improve athletic performance and recovery.

One easy, low-cost strategy is sleep extension—increasing the amount of time we spend asleep. This was explored in a 2011 study, where the authors supported a group of basketballers to increase their nightly sleep from 6.6 hours to 8.4 hours. As a result of increasing their sleep, the athletes improved their sprint speed, shooting accuracy, and reaction times, as well as their overall mood and feelings of fatigue. A similar study, this time from 2015 and in tennis players, showed that increasing the sleep time of athletes for a week improved their serving accuracy.

Another simple solution is improving the sleep hygiene of an athlete. In studies where athletes have ensured their room is cool and dimly lit, had access to sleeping aids such as ear plugs, and avoided technology use for 15-30 minutes before bed, they tend to sleep for longer and experience better quality sleep than those with poorer sleep hygiene. Even in studies where improving sleep hygiene doesn’t increase the quality of sleep, the athletes reported that they felt their sleep was improved, which is important in and of itself.

Interestingly, a couple of studies have identified that enhancing post-exercise recovery may enhance night time sleep. In one study, athletes utilized cryotherapy post-training, which maintained their sleep to a greater extent than in athletes who were in the control group. Similar results were reported in a study using red light irradiation as a form of recovery.

Enhancing post-exercise recovery may enhance night time sleep, says @craig100m. Share on X

The 2018 review article discussed above also outlines what an optimal sleep intervention for athletes might look like, which they summarize here. Similarly, a 2021 expert consensus article, published in the prestigious British Journal of Sports Medicine, also devised a “sleep toolbox” for practitioners to use with athletes. Their key steps are:

- Provide sleep education for athletes. In a sample of coaches, less than 50% had discussed sleep hygiene best practices with the athletes they worked with, even though the evidence suggested sleep hygiene education enhances the sleep of athletes. As such, sleep education is a low-cost first step to enhancing the sleep of your athletes.

- Sleep screen athletes and refer to help when needed. There are a number of sleep monitoring tools that could be utilized by athletes to better understand their sleep. Some of these require technology that may be expensive, but some are also low-cost, such as a sleep diary or sleep questionnaire. A common questionnaire that explores overall sleep hygiene is the Athlete Sleep Behaviour Questionnaire (ASBQ). It’s important to realize your scope of practice here; sleep issues may require support from medical practitioners. If you’re interested in finding out more about monitoring sleep, this review article provides an excellent summary.

- Encourage opportunities to nap. Sleeping in the daytime for a short period has a number of potential benefits, including improvements in alertness, concentration, motor performance, and overall mood. Naps can become increasingly important if the athlete cannot get sufficient sleep overnight—for example if they have an early morning wake-up for training or travel. There is even some evidence that naps are beneficial even when overnight sleep is sufficient.

- Utilize sleep banking and extension. Sleep banking is where athletes get more sleep before a period of anticipated sleep loss, for example before a long haul, overnight flight across multiple time zones. Sleep extension involves sleeping for longer than normal. Both have been shown to improve performance and, in the case of sleep banking, mitigate the effects of sleep loss.

Finally, in 2019, the NCAA Interassociation Task Force on Sleep and Wellness published their guidelines for optimizing sleep in high level athletes. Their recommendations are:

- Maintain a regular sleep schedule as much as possible, including on weekends.

- Seek bright light during the day, especially in the morning, and avoid bright light at night where possible.

- Keep the bedroom cool, dark, and comfortable.

- Avoid caffeine for at least 6 hours before bed, as well as other stimulants. Alcohol has a negative impact on sleep quality, and should be avoided.

- Avoid consuming excessive food and drink pre-bed, as these may disrupt sleep by increasing trips to the bathroom.

- Avoid obsessive clock watching if you can’t sleep; it increases mental activity, making it harder to fall asleep.

- If you find it hard to fall asleep at night, avoid napping during the day.

- Use beds for sleep only, with all other activities taking place outside of bed. This is especially true if you can’t sleep, with the recommendation being that you get up and try to sleep a short while later.

Final Takeaways

Getting enough sleep—and of sufficient quality—is critical for athletes, with poor sleep linked to reduced performance and increased injuries. Typically, both elite and youth athletes don’t get enough sleep, putting them at risk of underperformance.

There are many steps we can take to support the sleep of the athletes we work with, which are outlined in this article. It’s worth taking some time to consider how you might support the athletes you work with to get more sleep, as the research suggests many of us have the knowledge to do so, but don’t quite take that first step. Doing so may lead to the performance breakthrough your athletes deserve.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Barrett Snyder is a CSCS and holds an M.S. in Sports Management and a Master of Business Administration (MBA) from Drexel University. He is currently a J.D. and Ph.D. candidate.

Barrett Snyder is a CSCS and holds an M.S. in Sports Management and a Master of Business Administration (MBA) from Drexel University. He is currently a J.D. and Ph.D. candidate.

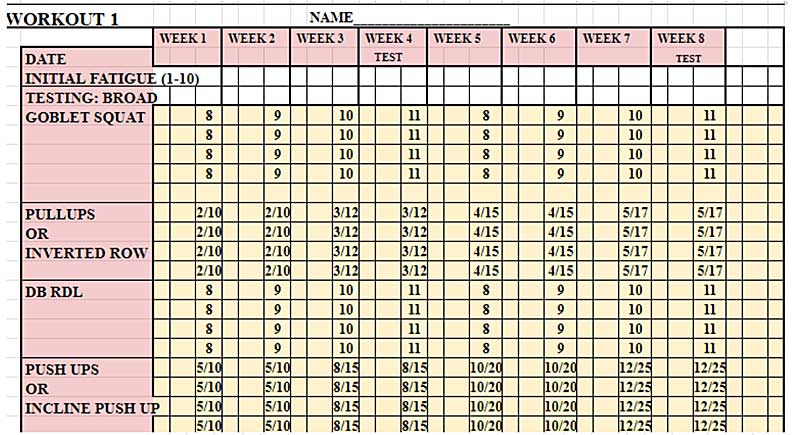

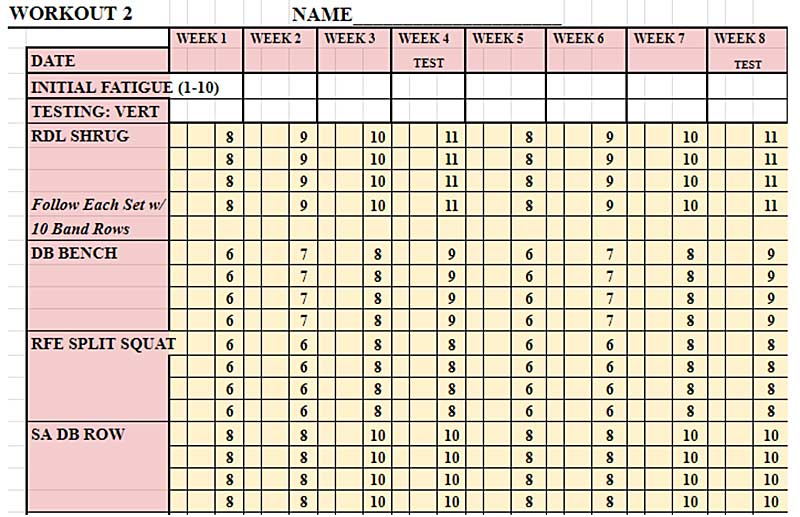

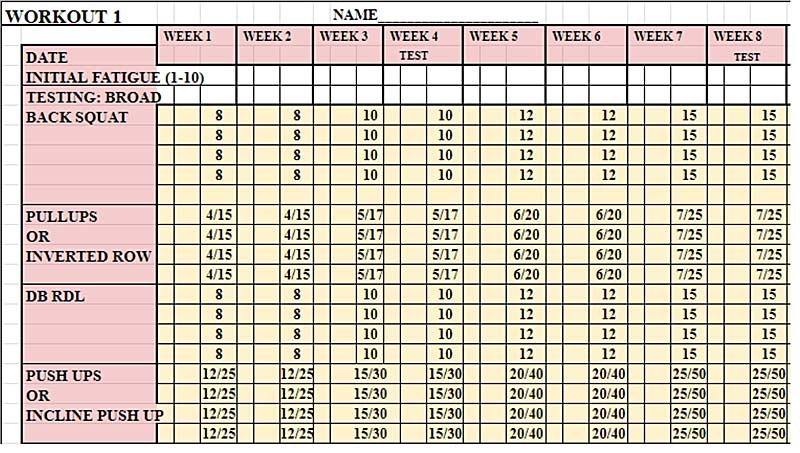

Alex Roberts is the Strength and Conditioning Coach at R. Nelson Snider High School in Fort Wayne, Indiana. In this role, he’s responsible for the year-round athletic development of all student-athletes. Coach Roberts’ main responsibilities are teaching strength training classes during the school day, leading after-school training sessions, and running the summer strength and conditioning program. He holds a Master of Science in Kinesiology and is CSCS certified through the NSCA.

Alex Roberts is the Strength and Conditioning Coach at R. Nelson Snider High School in Fort Wayne, Indiana. In this role, he’s responsible for the year-round athletic development of all student-athletes. Coach Roberts’ main responsibilities are teaching strength training classes during the school day, leading after-school training sessions, and running the summer strength and conditioning program. He holds a Master of Science in Kinesiology and is CSCS certified through the NSCA.