Strength coaches are always looking for the next best exercise or training tool, but often what’s “new” is rediscovering the best of what’s old. The iron boots I used over a half-century ago have been transformed into MonkeyFeet, and the Super Killer Squats I first read about in a muscle magazine in the 70s are now wedge board squats. Another training method that is getting a double-take is the abdominal rollout.

As “core training” is an important topic in physical and athletic fitness training, I want to trace the history of a few of the most popular methods to train the abdominals. Included will be a discussion on the ab wheel, sit-ups, crunches, ab rockers, and ab crunch machines. After discussing the good, the bad, and the worthless of these methods and devices, I’ll make a case for the barbell rollout as a “go-to” core exercise for athletes interested in achieving athletic superiority.

(Lead photo by Karim Ghonem)

Enter the Ab Wheel

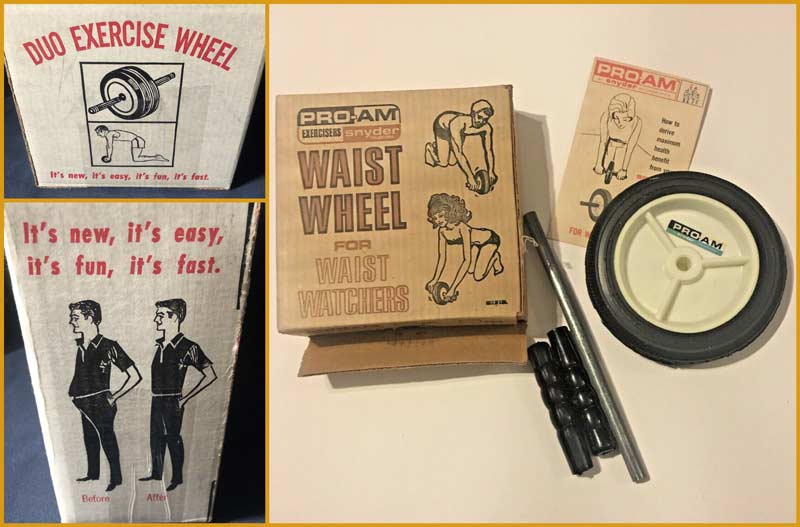

I was introduced to this device in the late 60s by magazine advertisements. The ab wheel was promoted to the general public as an easy tool to tone your abs and reduce your waistline (Image 1), and sales quickly exceeded millions of dollars.

For the untrained or deconditioned, the high levels of tension an ab wheel can produce may cause abdominal injury and lower back pain, particularly if the exercise is performed incorrectly. To reduce the risk of injury, it’s essential to maintain a neutral spine (posteriorly rotating the pelvis) throughout the exercise. More specifically, the exercise should begin with the lower back flat or slightly rounded, and you should extend as far as you can maintain this posture.

For the untrained or deconditioned, the high levels of tension an ab wheel can produce may cause abdominal injury and lower back pain. Share on XThe end range of an ab wheel (when the arms begin to extend) is especially challenging. One way to assist beginners is to perform the exercise while kneeling on a low platform, such as an aerobic step. An analogy would be a push-up progression where you start from a standing position with your hands on a wall (vertically), move to a push-up on a bench where your body is positioned at an angle, then finish on the floor (horizontally).

There are many types of ab wheels. One type has a spring attachment that winds up when you extend and uncoils to assist you on the return. Fitness model and former collegiate softball player Jordan Dwyer demonstrates one of these devices in Video 1.

Video 1. The basic ab wheel exercise is performed on the knees. This modern ab wheel unit has a spring device that helps the athlete return to the start.

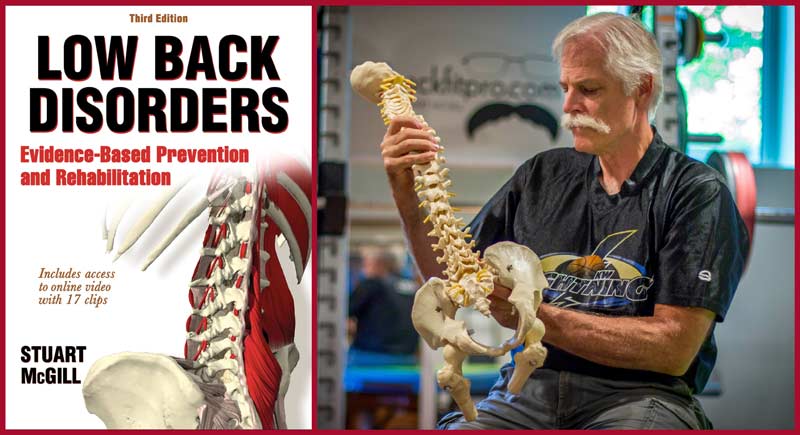

Not living up to the promise of reducing waistlines quickly contributed to a lack of interest in the ab wheel and a renewed interest in traditional exercises, such as sit-ups. “Bootcamp” programs, inspired by military training, became popular—but not for long, thanks to the pioneering research of Spine Biomechanics Professor Stuart McGill (Image 2).

McGill’s research on the effects of spine bending and compressive loading included direct loading on pig cadavers, which he says are a reasonable representation of human spines. He also conducted epidemiological investigations comparing groups that performed sit-ups and those that did not. McGill concluded that flexion of the spine during these exercises and the muscle activity needed to perform them created stresses that could eventually damage the discs. McGill added that he was involved in several case studies involving military and law enforcement personnel who were required to perform the sit-up test for time. He said they all “had a history of discogenic back disorders, which reduced when sit-up training was replaced with a core stabilization approach.”

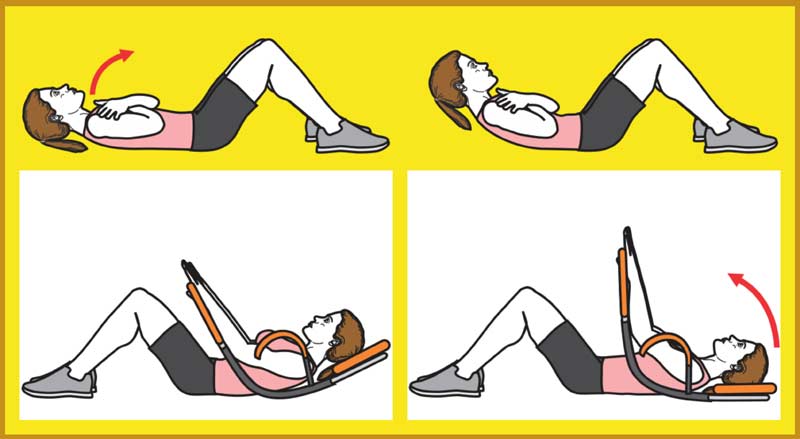

With sit-ups getting a bad rap, many in the fitness community endorsed crunches as the go-to abdominal exercise. Crunches were easy to do and required no special equipment. Performing crunches on a Swiss ball also became popular because they increased the range of motion of the exercise and, unfortunately, the potential risk of a sports hernia (i.e., athletic pubalgia).

With sit-ups getting a bad rap, many in the fitness community endorsed crunches as the go-to abdominal exercise. Share on XNext, home ab crunch rocker devices soon appeared that supported the neck to relieve neck strain (Image 3). However, there are several ways to prevent neck strain with crunches. One is to reduce tension on the back of the neck by pressing your fingers against your forehead. Through an effect known as reciprocal inhibition, providing resistance that causes the muscles on the front of the neck to contract will cause the muscles on the back of the neck to relax. That said, ab rockers and traditional crunches do not provide enough resistance to create a significant training effect for more than a short period. This issue inspired the development of seated ab crunch machines.

Seated ab crunch machines provide progressive resistance, usually with a selectorized weight stack. In the early 80s, I was a Nautilus instructor at the San Jose YMCA (where many elite track and field athletes trained, including world record holder Al Feuerbach). This YMCA, along with many others, purchased a complete circuit of Nautilus machines.

Unquestionably, the abdominal crunch machine was the most popular, and members wanted to perform several sets (which was against the Nautilus protocol, but I often let them slide if there wasn’t a line). Many other gym instructors also told me about the popularity of these ab crunch machines; other equipment manufacturers took notice with their own variations.

Although crunch machines are here to stay, the next core training phase the general public latched onto was planks. Planks also got the seal of approval from McGill.

And that brings us back to the ab rolling, which could be considered a dynamic form of planks.

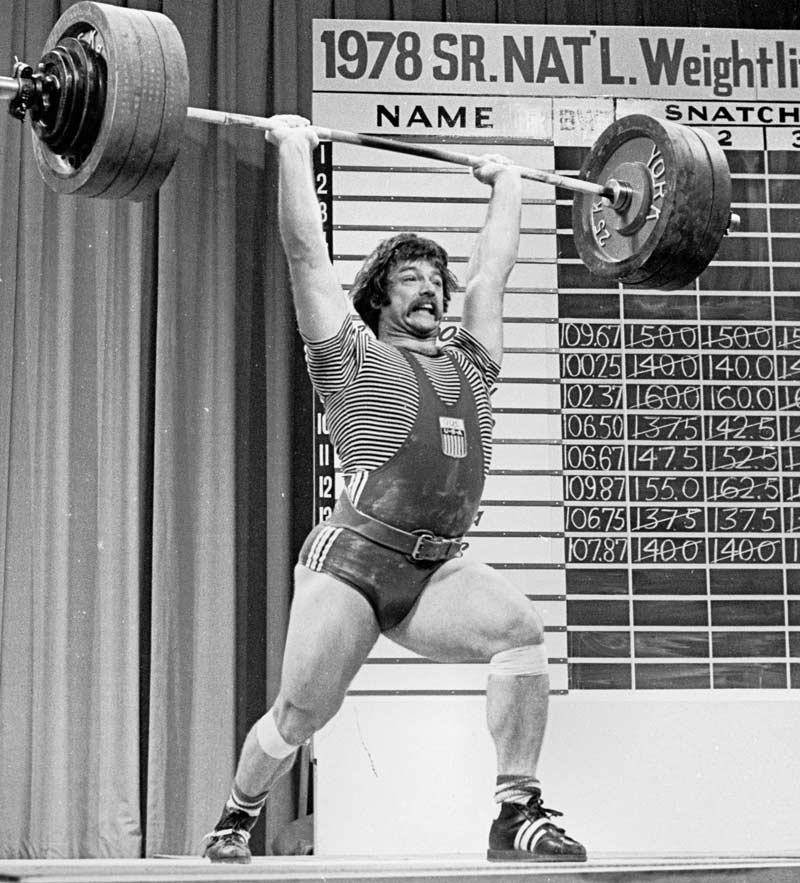

Although it’s reasonable to assume that those who created the ab wheel invented the exercise, its history goes back to the early days of professional strongmen. To perform the exercise, they would use a barbell so they could progressively increase their resistance (Image 4).

Although it’s reasonable to assume that those who created the ab wheel invented the exercise, its history goes back to the early days of professional strongmen. Share on X

One notable Iron Game athlete who performed barbell rollouts was Mark Cameron (Image 5). In 1980, Cameron became the second (and still the lightest) American to clean and jerk 500 pounds. He told me he would use 242 pounds (110 kilos) for reps during workouts.

One of my colleagues who has been prescribing barbell rollouts to his athletes for over 30 years is strength coach and posturologist Paul Gagné. He says it’s one of the most unique abdominal exercises “because the range of motion is large and it’s all anti-gravity.” However, he only prescribes it after a preparatory period of lower abdominal training—let me expand on his approach.

Facts and Fallacies of Lower Ab Training

The rectus abdominis extends from the top of the sternum and rib cage to the pubic bone and is the muscle that gives us the envied “six pack” (Image 6). The rectus abdominis is a single muscle, but for program design purposes, Gagné divides it into two sections: supraumbilical (above the belly button) and subumbilical (below the belly button).

The entire rectus abdominis is somewhat activated in nearly every abdominal exercise, but Gagné says it is possible to emphasize specific segments. Compare this approach to how bodybuilders (including Arnold!) target the upper area of their pectorals by performing bench presses on an incline.

The entire rectus abdominis is somewhat activated in nearly every abdominal exercise, but Gagné says it is possible to emphasize specific segments. Share on XMany strength coaches are fond of saying, “Train movements, not muscles.” In the case of the lower abdominals, Gagné asserts that all macro movements depend on micro movements. “Functional training that simulates the movements in sports is fine, but only so long as each segment is strong enough to coordinate those movements properly.”

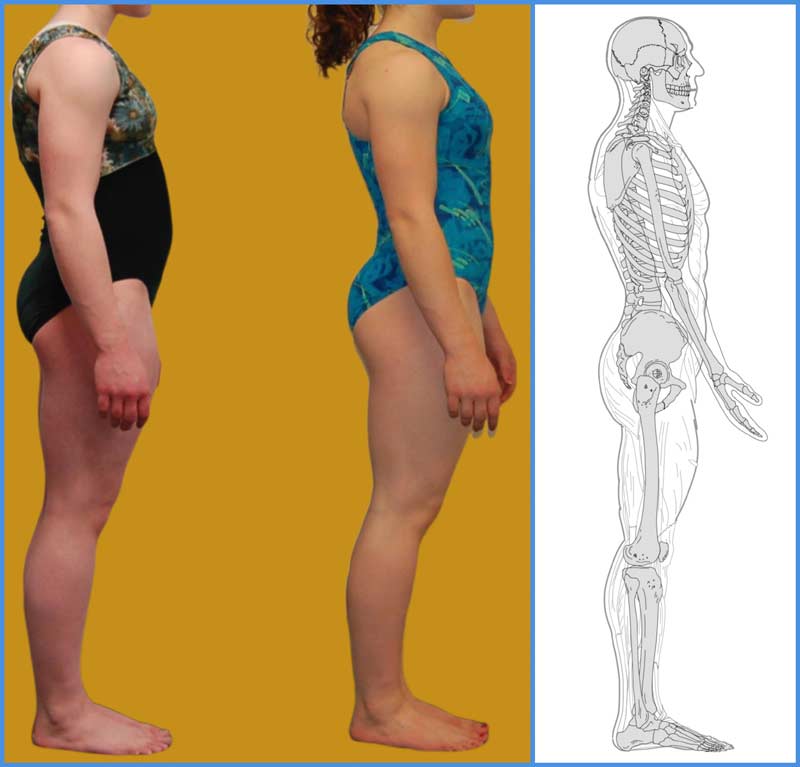

The lower abdominals play a critical role in preventing injuries and producing the highest levels of athletic performance. For example, lower abdominal weakness may cause the pelvis to rotate excessively forward during sprinting. These mechanics can affect stride length, increase stress on the hamstrings, and reduce the shock-absorbing qualities of the spine (Image 7). Research supports this theory, even suggesting that pelvic posture may be more important for preventing hamstring injuries than stretching.

A study on the link between hamstring injuries and flexibility was published in 1993. The 34 subjects included rugby, hurling, and Gaelic football athletes. “The results of the study indicate that while differences in hamstring flexibility are not evident between injured and noninjured groups, poorer low back posture was found in the injured group.” They concluded that coaches should regularly monitor the posture of these athletes.

Gagné says the problem is compounded if one side of the lower abdominals is significantly weaker. This imbalance could cause excessive spinal rotation, leading to possible disc injury.

According to Gagné, before performing barbell rollouts (or using an ab wheel), you should have sufficient lower ab coordination and strength to maintain a neutral spine during the exercise. This involves screening athletes with two simple tests.

Abdominal Testing Basics

The first test determines if you have the body awareness (proprioception) to activate the lower abs.

Lie on your back with your knees bent at 90 degrees. Place your hands on your chest and rest your head on the ground. Try to lift your hips straight up a few inches, exhaling hard as you do so (Image 8). If you can’t perform this movement without pulling your knees towards your head, or if you have to brace your elbows on the floor or lift your head, you have weak lower abdominals. “This lower abdominal raise is just about the only movement you could say is purely subumbilical,” says Gagné.

’This lower abdominal raise is just about the only movement you could say is purely subumbilical’, says Gagné. Share on X

If one of his athletes fails the lower abdominal strength test, Gagné would have them practice this movement (or other exercises) until they can pass it. Often, athletes can pass the test after just a few training sessions.

The second test measures the coordination between the abdominal muscles and the muscles that flex the hip. It is discussed in the popular physical therapy textbook Muscles: Testing and Function, first published in 1949. The difference between this test and a straight-leg raise exercise is that you must keep the lower back pressed against the floor during the movement.

To perform the test, have a partner place their hands underneath your lower back, lightly touching the vertebrae directly under your belly button. Have your partner extend your legs until they are perpendicular to the floor, supporting them briefly. Press your spine against the floor and slowly lower your legs, exhaling as you do so, with your partner holding their free hand a few inches away from your ankles so your legs don’t collapse (Image 9).

To score 100 percent, a male must lower their legs all the way down without arching their lower back, and a female to about 15 degrees from the floor. The two standards are needed because women carry more of their total muscle mass in their lower extremities.

The two standards are needed because women carry more of their total muscle mass in their lower extremities. Share on X

With those prerequisites out of the way, you’re ready for the next phase of abdominal training: barbell rollouts!

Next-Level Ab Training with Barbell Rollouts

When an athlete is ready for barbell rollouts, there are several ways to progress. Gagné recommends starting from the knees, then from a low platform, and finally (for the super advanced) from a standing position. Let’s take a closer look at each.

Level 1: Kneeling on the Floor. As with the ab wheel, one of the key technique points in performing a barbell rollout is to keep the spine in a neutral position (Image 10).

Placing a towel or padding under your knees will make the exercise more comfortable. You should initiate the exercise by moving your hips forward and stopping if you feel your lower back arching. Only when your hips have moved as far as they can do you initiate the use of your arms.

During the exercise, keep your head in line with your spine, which will help prevent you from arching your lower back. Also, grip the barbell hard to stabilize your upper back. Gagné says gripping hard is also an exercise to help correct round shoulders.

As for breathing, during these barbell rollouts, you exhale during the most challenging part of the exercise. More specifically, you inhale as you extend, hold your breath at the fully-extended position, then slowly exhale (with pursed lips) as you return.

To help you perform the exercise correctly, wrap an elastic band around your upper thighs, close to your hips (Video 2). Have your partner stand behind you. As you extend, the pull of the band will help you maintain a neutral spine and enable the trainee to extend further.

Video 2: Using a band across the upper thighs provides feedback on exercise posture and assists the trainee with the exercise.

Level 2. Kneeling on Low Platform. This variation requires a low platform (Image 11), about 4 to 6 inches, such as the height of an aerobic step. While using a platform makes the ab wheel exercise easier, it’s harder with a barbell. “Because of the barbell’s higher position, I prefer performing two progressions before standing,” says Gagné.

An alternative to kneeling on a low platform is to use smaller diameter plates, although they tend not to roll as smoothly as the large bumper plates. Again, placing a towel or some other padding under the knees would make the exercise more comfortable.

Level 3. Standing. This is the most challenging variation and requires good hamstring flexibility. You should perform it on a non-slip surface or with your feet against a wall to prevent slipping. Before trying it, do a few workouts without the barbell to get accustomed to the movement (Image 12).

From standing is the most challenging variation of barbell rollouts and requires good hamstring flexibility. Share on X

When you’re ready for the barbell, start with the barbell close to a wall or power rack to prevent you from collapsing and falling facedown (Image 13). After a few sessions, you should be comfortable with the movement to perform it away from a wall.

Start with the bar close to the shins, head down, and slowly extend as far as possible under control (14). Don’t be discouraged! You may only be able to extend a few inches at first. If hamstring flexibility is an issue, start with your knees slightly bent until your flexibility improves from performing this movement.

Coach Gagné has developed many other variations of barbell rollout exercises, along with more extensive abdominal training protocols. However, the approach described here is a good start and one that he has used with Olympians, professional athletes, and the general population. The bottom line is to find ways to increase the resistance progressively with abdominal training. Barbell rollouts are a practical option to help you accomplish just that!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

McGill, S. Personal Communication. June 26, 2023.

McGill, S. Low Back Disorders: Evidence-Based Prevention and Rehabilitation, 3rd Edition. Human Kinetics, May 8, 2015.

Schwarzenegger, A. The New Encyclopedia of Modern Bodybuilding, pp. 308-309. Simon & Schuster, 1998.

Hennessey L., and Watson A.W. Flexibility and posture assessment in relation to hamstring injury. Br J Sports Med. 1993 Dec;27(4):243-6.

Kendall, F.P., et al. Muscles Testing and Function, 4th Edition, pp. 156-157. Williams & Wilkins, 1983.