Despite the popularity of core training in fitness, rehab, and performance spheres, I have a sneaking suspicion that we aren’t all talking about the same thing. I’m not even sure we all agree on what the core even is, and maybe more importantly, how to best monitor and train it to reduce injuries or improve performance.

Let me explain.

You often hear coaches talk about training the “core,” but what does that even mean? I liken it to someone saying they trained their “legs.” What specifically did you train? What muscle groups? What contraction types and speeds? Endurance, max strength, or power? Which planes of motion? It’s such a vague descriptor that it’s essentially meaningless.

I’m not even sure we all agree on what the core even is, and maybe more importantly, how to best monitor and train it to reduce injuries or improve performance, says @CoachGies. Share on XThe term “core training” is often used as a catch-all for low-intensity exercises that isolate certain trunk muscles, but not always. Coaches will lump together rotational medicine ball throws, crawls, carries, loaded trunk movements, and other exercises under the singular banner of core stability.

Despite decades of related research on the topic, three distinct dilemmas have emerged that I believe are holding back our industry’s understanding and implementation of core training in both the S&C and rehab professions:

- No universal understanding of what core stability even is.

- Inadequate testing methods.

- No clear training framework.

But before we explore my justification for this hot take, it would be worthwhile to review how people can hold such differing opinions from one another. There are two cognitive biases that may help illuminate these problems (they might also help you understand the never-ending source of S&C Twitter conflicts):

- The Anchoring Bias.

- The False Consensus Effect.

The anchoring bias is the tendency to be overly influenced by the first piece of information we hear (for example, “Core training can prevent back injuries” or “The best core training involves anti-extension/rotation exercises”). All future information is then processed through this reference point rather than being objectively viewed.

It’s also very difficult to counteract this bias if you aren’t actively trying to challenge your priors (echo chambers, anyone?). Think of it this way: if you are a young intern and the facility you begin your career at is adamant that barbell squats and deadlifts are all an athlete needs for core development, you will view all future core stability information through that lens. Similarly, if you are a physiotherapy student and are told every patient needs isolated motor control exercises to engage the core properly, you are more likely to continue with those views going forward.

The false consensus effect is the tendency to overestimate how much others agree with your beliefs, behaviors, attitudes, and values. You overestimate the number of individuals that think like you and believe the vast majority of people share your training beliefs. Most coaches likely believe the rest of the industry thinks like them, and those who disagree are just outliers (or idiots). If you think most people think like you, you will be less likely to seek out differing opinions to challenge your beliefs because, well, why would you if you’ve got things figured out?

In an industry that loves to dichotomize anything and everything, core training is no exception. Some coaches preach the need to include isolated and specific exercises to target the core, or else this area will become underdeveloped and expose you to injury or poor performance. Others are confident that no direct training is needed and that barbell exercises and athletic movements will train the core just fine. Some think the spine shouldn’t move and be trained in static positions or with bodyweight movements only; others believe the spine should move freely and be loaded, sometimes in extreme positions.

It seems that many coaches hold strong beliefs on this topic, with many believing their views on core training are right while others are wrong.

The Three Dilemmas Holding Us Back

As I present the rest of the article, try to keep both the anchoring bias and false consensus effect in mind. Perhaps you will start to reflect on how you’ve fallen for both of these, not just around core training but with other training concepts as well.

1. The Definition Dilemma

In 1964, Justice Potter Stewart was famously quoted as saying, “I know it when I see it” when attempting to define pornography. The same could be said about the core and core training. Most people would largely know what those terms mean and what a core exercise is if they saw one performed.

But does everyone have the same understanding of what the core or core training is despite using the same terms?

Are we really speaking the same language?

The muscles attaching to the spine are often referred to as the “core”; however, the exact anatomical makeup of the core is not unanimously agreed upon among coaches and researchers.1 The functional capacity of these muscles is often termed “core stability” and has been the subject of extensive scientific investigation over the last 30 years. However, despite extensive research, there is still considerable confusion as to the exact definition of core stability.2–4

Without clear definitions in place, the interpretation of research data depends on the reader’s CURRENT conceptual understanding of core stability. We see this play out all the time on social media. Share on XWithout a clear series of definitions in place, the interpretation of research data is dependent on the reader’s current conceptual understanding of core stability. We see this play out all the time on social media. A study comes out, and there are wildly different interpretations of the results and conclusions, which leads to extensive debates, name-calling, and confused bystanders. As such, several researchers have highlighted that research cannot advance on this topic unless there is some definitional consensus.3–5

Many of the definitions in use today are too broad or too vague to provide much practical worth. They do little to inform coaches on which physiological qualities to address. Researchers have suggested that the diversity of definitions in the literature hampers the ability to summarize research findings and draw clear conclusions.6 Some of the definitional differences could be due to the context in which they are viewed.3 For example, in rehabilitation sectors, where treatment goals revolve around decreasing pain and returning to function, the concept of core stability and how to train it may look different than in S&C circles, where the priority is improving highly dynamic sporting movements.

Broadly speaking, there are three common terms used in the literature:7

- Core endurance: The ability to maintain a position for an extended period or perform multiple reps.

- Core strength: The ability to produce muscular force or intra-abdominal pressure.

- Core stability: The capacity of the stabilizing system to maintain intervertebral neutral zones during various activities.

What causes confusion is that these terms are often used interchangeably in the literature. Similarly, there is no agreement on the appropriate use of these terms in practical circles.1

Another term that is becoming more prevalent is “lumbopelvic control” (LPC)—or some variation of this—which is defined as “the ability to actively mobilize or stabilize the lumbopelvic region in response to internally or externally generated perturbations.”8 Other terms commonly used to describe the core include trunk, torso, and fascial slings. Without a clear agreement on what the definitions are and when to best use the terms, it ultimately boils down to the coach’s interpretation and previous experience with using those terms.

2. The Testing Dilemma

There are many established and validated testing procedures that help assess a wide range of functional and athletic capacities. These include muscular strength, muscular endurance, specific energy systems, power, and linear and multidirectional speed. In regard to testing core stability, there seem to be no validated tests capable of assessing the full spectrum of functional capacities of the core.9

For instance, the most commonly used tests for assessing the core consist of timed isometric holds (e.g., prone plank). Although these muscular endurance tests are reliable,10 they do not reflect the force and velocity demands seen during sporting activities and are likely to be inappropriate for athletic populations.9 It’s important to note that many of the most common core stability assessments were originally developed for individuals with low back pain (LBP).11 These tests would obviously be performed at a slower speed or be isometric in nature, rather than generating rapid muscular contractions, yet have seemed to permeate performance spheres and athletic testing batteries.

It’s important to note that many of the most common core stability assessments were originally developed for individuals with low back pain, says @CoachGies. Share on XSimilarly, there are currently no practically viable or validated methods available to assess maximal core strength for S&C coaches, although this quality appears relevant to athletic populations.12,13 Critically, it remains unknown whether—or how—coaches are monitoring core stability in practice. This is an important point because core stability training is a widely used tool in our industry, with nearly every coach implementing some sort of protocol to enhance this area. Yet, without established and validated tests to assess distinct physical qualities associated with core stability (e.g., strength versus endurance versus power), it’s impossible to discern the practical value of various core stability training programs and protocols.

3. The Training Dilemma

There are many widely accepted and validated training frameworks to develop either global physiological capacities (e.g., maximum strength or peak power) or specific morphological adaptations (e.g., eccentric training to increase muscle fascicle length). The same doesn’t seem to be true regarding training the core, as there is no broadly accepted training framework. To make matters worse, most coaches believe their way of training the core is superior or believe most coaches are doing what they are doing already (refer back to the Cognitive Biases section).

As with testing methods, many of the core stability training recommendations in the literature have been developed from research examining rehabilitation methods for chronic LBP.14 These exercises have since spread to training programs designed for athletes but have been heavily criticized as inappropriate for improving physical performance in healthy athletic populations.15 You can see how these rehab-based recommendations have seeped into the industry, as most coaches have at least heard concepts relating to “activate your core” prior to doing some sort of movement or even, more popularly, Dr. Stuart McGill’s “Big 3” exercises to prevent LBP.

Due to the absence of clear and robust training frameworks, current practical applications seem to vary extensively.1 There is considerable debate as to whether core stability should be trained using isolated exercises, classical barbell movements, and/or athletic movement drills.4,15,16 I’m sure every coach has heard people debate the merits of specific exercises or methods for developing the core.

Several attempts at creating more complete and well-rounded training frameworks have been proposed in the literature.3,17 However, whether these models improve performance or prevent injury has not been rigorously tested or validated. This bears repeating: There are currently no validated—or thoroughly tested—training frameworks for developing the core.

This bears repeating: There are currently no validated—or thoroughly tested—training frameworks for developing the core, says @CoachGies. Share on XEither the science is sparse or inadequate (e.g., training interventions with too few subjects or too short a duration), or the programs are based more on theory or practical coaching experience. This is not to say training methods designed from coaching experience aren’t valid or useful, but we may need to temper the strength of our beliefs if the scientific backing just isn’t there. This lack of guidance, coupled with opposing opinions on best practices, leaves S&C coaches with a confusing diversity of mixed messages.

So, What Do We Do Now?

While it’s beyond the scope of this article to solve any of these dilemmas, that doesn’t mean all is lost. There are two areas of improvement that we can work on from both a scientific and practical perspective.

1. Say What You Mean, and Mean What You Say!

First, there needs to be an alignment of terminology. Precision of speech is critical if we are to effectively convey our thoughts to athletes and other coaches. Using similar-sounding—yet fundamentally different—terms does little to advance our understanding or application of core training.

Look, I get it; when talking to an athlete or someone who isn’t a coach, using some terms interchangeably might not make much difference in the quality of training received. But as a profession, the more precise and aligned we can be in our terminology, the better. I would urge you—the reader—to be aware of how these terms are being used in both academic and practical contexts.

Academically

When reading a paper on core stability training, dig into the methods section and see how the authors actually define these terms and what exercise interventions they use. I bet you’d be surprised at what you find!

Many research papers that assess or implement “core strength” methods (as specified by their titles, introductions, and conclusions) often use muscle endurance exercises and protocols (e.g., planks, sit-ups, or other high-rep bodyweight exercises). For argument’s sake, this would be akin to a research paper examining “lower body strength training” and concluding it doesn’t have an impact on vertical jump ability in high school athletes. But if the training intervention only utilized wall sits as their strength training exercise, I’m sure many coaches would take issue with people saying that lower-body strength training isn’t useful for athletes because this doesn’t look at the whole spectrum of lower-body strength training exercises or methods.

I would also assume that wall sits weren’t the first exercise you thought of when you read “lower body strength training.” You would probably define it as a muscular endurance exercise or a long-duration-yielding isometric, and that’s my point. From a methodology standpoint, understanding precisely what a research paper is investigating will allow you to determine the merits of the exercises investigated rather than assuming their worth based on the general terms used by the authors had you not dug a little deeper.

Practically

Nearly all coaches will have assumptions and personal preferences about what constitutes “core training.” It’s almost so general of a term as not to really mean much. If a coach says they did core training with an athlete, you might have an assumption of what they did, but you really have no idea what exercises were used or what physical qualities were developed. Some coaches might be more biased toward dynamic spinal movements with external loads, some might only implement isometric bodyweight holds, and others might view the classical barbell exercises as sufficient.

Consider how Alex Natera has improved our practical understanding of isometric training by breaking the concept into several distinct categories to target specific qualities for field sport and track athletes. Or how Lachlan Wilmot’s Plyometric Continuum caught fire because it categorized jump-based exercises into distinct and specific categories to improve exercise selection. Rather than falling back on umbrella terms like “isometric training” or “plyometrics,” they expanded those concepts and brought specific terminology to the forefront so everyone spoke a similar language.

Without a clear set of terms to describe the complexity of core training, it will be tough to determine exactly what other coaches mean when they say ‘core training,’ says @CoachGies. Share on XWithout a clear set of terms to describe the complexity of core training, it will be tough to determine exactly what other coaches mean when they say “core training.” Again, I would urge you to think deeply about which terms you use and if they make the most sense for the physiological adaptations you are looking to develop or the phase of training for the athlete. A non-exhaustive list of possible terms you can use to describe core exercises more precisely includes:

- Core strength (e.g., 5–8RM weighted decline sit-up)

- Core endurance (e.g., bodyweight sit-ups to volitional exhaustion)

- Core power (e.g., split stance rotational medball throw)

- Trunk flexion (e.g., sit-up), hip flexion (e.g., hanging leg raise), lateral trunk flexion (e.g., side bend), trunk/hip extension (e.g., 45° back extension), trunk rotation (e.g., Russian twist)

- Prone (e.g., front plank) or supine (e.g., deadbug)

- Dynamic (pro-movement, e.g., sit-up) or static (anti-movement, e.g., Pallof hold)

- Isolated (e.g., crunch or side plank) or global (e.g., back squat or Turkish get-up)

- Low load (e.g., bodyweight front plank for max time) or high load (e.g., front plank with 45-pound plate on hips for 20 seconds)

- Lumbopelvic stability (e.g., bird dog with minimal movement in the lumbopelvic region)

The more precise your terminology, the more easily coaches can understand what you are actually implementing. You will also be able to assess whether your “core training” program checks off all the boxes you want it to or if there is a quality you might be neglecting.

2. Utilize a More Comprehensive Core Training Framework

Finally, the development of a more comprehensive core training framework for athletic performance is needed. Often, core training can be an afterthought, programmed haphazardly at the end of sessions or, even worse, utilized as a “filler” to check a box.

Like many coaches, I was intrigued by Lachlan Wilmot’s Plyometric Continuum, as it opened my eyes to how poorly I was prescribing jump training with my athletes. I decided the way I implemented core training could benefit from a similar framework of simple and clear progressions for the beginner to the advanced athlete. This way, I could more easily slot an athlete into the progression streams that make the most sense or select the best exercises for the sport or time of year.

Thus was born my version of a Core Training Continuum.

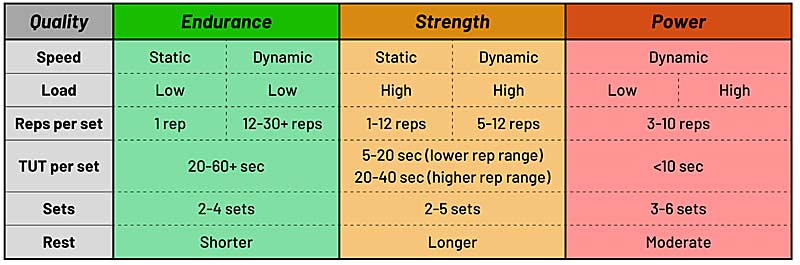

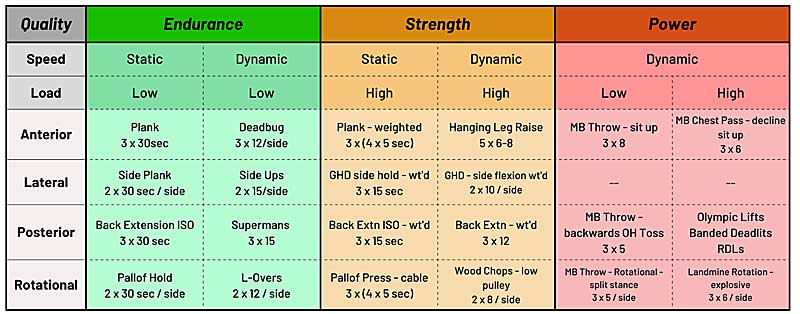

This breaks down core training into what I feel are the big rocks coaches need to consider when progressing athletes or selecting the most appropriate stimulus for the time of the year. It also provides guidelines on how to prescribe the volume and loading for each category to ensure the actual adaptation you are after is properly developed. The key categories I identified in regard to developing a well-rounded trunk consist of:

- Endurance – Static (long-duration submaximal holds)

- Endurance – Dynamic (high-repetition submaximal movements)

- Strength – Static (short-duration maximal holds)

- Strength – Dynamic (low-repetition maximal movements)

- Power (high rate of force development movements)

All five of these categories are further divided into four subcategories pertaining to the location of the torso being trained.

- Anterior trunk (trunk/hip flexion or anti-extension, prone or supine)

- Lateral trunk (lateral flexion or anti-lateral flexion)

- Posterior trunk (extension or anti-flexion)

- Rotational (rotation or anti-rotation)

*Notes:

- Strength – Dynamic – Posterior could be lumped into the hip extension movement category rather than a specific core training category.

- Power – Lateral trunk would likely be too difficult to perform; the Rotational category would likely be sufficient.

- Power – Anterior and Posterior trunk may be considered full-body power drills and not strictly a core training category.

Nearly all core exercises can be categorized under this framework to create a menu of possible training options when programming for specific athletes. This continuum can have applications in long-term athlete development, rehabilitation, or performance settings and be used to select individual exercises based on the needs of an athlete or to create core circuits targeting a specific quality in several torso locations.

The problem with making a training model like this too detailed or all-encompassing is that it becomes too rigid to work in the real world, says @CoachGies. Share on XI made this framework as simple and straightforward as possible. The problem with making a training model like this too detailed or all-encompassing is that it becomes too rigid to work in the real world. Obviously, these guidelines can be broken in the right context, but these guidelines will be suitable for the majority of situations.

Is it perfect? No. But no training model is. The more coaches can implement similar types of frameworks for implementing core training, while using clear terminology on what they are doing, the more effective their training interventions will be.

Final Thoughts

Outliers aside, there doesn’t seem to be a widely accepted method for developing all facets of core function over the long term. Some facilities or coaches may have developed systems like this in isolation, but to move our industry forward, these ideas need to reach a broader audience, with more rigorous and long-term studies performed to improve our confidence in their worth.

The goal is that this article helps shine a light on some of the dilemmas surrounding our industry’s current assumptions on core training, as well as some of the underlying cognitive biases responsible. Finally, it’s my hope that the Core Training Continuum can help coaches develop their own framework for developing better core training programs.

The preceding article is based on Nick’s master’s thesis, “Current Perspectives around Core Stability Training in the Sports Performance Domain.” To read the full text, click here.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Clark DR, Lambert MI, and Hunter AM. “Contemporary perspectives of core stability training for dynamic athletic performance: A survey of athletes, coaches, sports science and sports medicine practitioners.” Sports Medicine – Open. 2018;4(1):32.

2. Borghuis J, Hof AL, and Lemmink KAPM. “The Importance of Sensory-Motor Control in Providing Core Stability.” Sports Medicine. 2008;38(11):893–916.

3. Hibbs AE, Thompson KG, French D, Wrigley A, and Spears I. “Optimizing performance by improving core stability and core strength.” Sports Medicine. 2008;38(12):995–1008.

4. Wirth K, Hartmann H, Mickel C, Szilvas E, Keiner M, and Sander A. “Core Stability in Athletes: A Critical Analysis of Current Guidelines.” Sports Medicine. 2017;47(3);401–414.

5. Martuscello JM, Nuzzo JL, Ashley CD, Campbell BI, Orriola JJ, and Mayer JM. “Systematic review of core muscle activity during physical fitness exercises.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research/National Strength & Conditioning Association. 2013;27(6):1684–1698.

6. Silfies SP, Ebaugh D, Pontillo M, and Butowicz CM. “Critical review of the impact of core stability on upper extremity athletic injury and performance.” Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy. 2015;19(5):360–368.

7. Saeterbakken AH. “Muscle activity, and the association between core strength, core endurance and core stability.” Journal of Novel Physiotherapy and Physical Rehabilitation.” 2015;2(2):028–034.

8. Chaudhari AMW, McKenzie CS, Pan X, and Oñate JA. “Lumbopelvic control and days missed because of injury in professional baseball pitchers.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2014;42(11):2734–2740.

9. Prieske O, Muehlbauer T, and Granacher U. “The Role of Trunk Muscle Strength for Physical Fitness and Athletic Performance in Trained Individuals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Sports Medicine. 2016;46(3):401–419.

10. Waldhelm A and Li L. “Endurance tests are the most reliable core stability related measurements.” Journal of Sport and Health Science. 2012;1(2):121–128.

11. Shinkle J, Nesser TW, Demchak TJ, and McMannus DM. “Effect of core strength on the measure of power in the extremities.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research/National Strength & Conditioning Association. 2012;26(2):373–380.

12. Park J-H, Kim J-E, Yoo J-I, Kim Y-P, Kim E-H, and Seo T-B. “Comparison of maximum muscle strength and isokinetic knee and core muscle functions according to pedaling power difference of racing cyclist candidates.” Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation. 2019;15(3):401–406.

13. Raschner C, Platzer H-P, Patterson C, Werner I, Huber R, and Hildebrandt C. “The relationship between ACL injuries and physical fitness in young competitive ski racers: a 10-year longitudinal study.” British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2012;46(15):1065–1071.

14. Huxel Bliven KC and Anderson BE. “Core stability training for injury prevention.” Sports Health. 2013;5(6):514–522.

15. Lederman E. “The myth of core stability.” Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2010;14(1):84–98.

16. Behm DG, Drinkwater EJ, Willardson JM, and Cowley PM. “The use of instability to train the core musculature.” Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism. 2010;35(1):91–108.

17. McGill S. “Core Training: Evidence Translating to Better Performance and Injury Prevention.” Strength & Conditioning Journal. 2010;32(3):33.