As S&C coaches, the role and responsibilities of a nutritionist often fall onto our plate by default. Why? We are the “experts” in the human body, we train the athletes, and nutrition falls within the scope of physical preparation.

While it would certainly be beneficial to have a registered dietitian on staff at your school or facility, the industry has yet to expand into every space and every sector—so if you find yourself wearing the “nutritionist hat” at your institution or space, here are five key tips to get you going and help you be an asset in that area.

1. Get Certified

Yes, it is okay to give recommendations on what athletes should eat without being a certified dietitian (depending on where you live). This can be as simple as letting athletes know how much protein they should be eating per day, how many carbs they need to fuel themselves for their activity level, how much water to drink to stay hydrated, or how many calories they need for their body composition changes (muscle gain, fat loss, or maintenance).

For me, this all comes down to how educated you are on the subject. After all, the more you know, the more you can confidently share with your athletes. Instead of going back to school for a master’s degree in sports nutrition (or diving in and becoming an RD), getting a certification can help you learn as well as prove you are at least somewhat qualified in this area.

The first thing to do when tackling the nutrition side of training is to ensure you know what you’re talking about; the second is to ensure you know how to communicate it to your athletes/clients. Share on XI have my Precision Nutrition (PN) Level 1 certification and highly recommend it. I wanted a certification that not only gave me expertise on the science of nutrition and how the body uses food for fuel but also taught me how to coach my clients through making big changes—which are inevitable when dealing with nutrition. There are other certifications that might dive deeper into the actual science and bioenergetics of nutrition (ISSN, ISSA), but PN offered both the science and coaching I was looking for, so I went with it. After all, the first thing to do when tackling the nutrition side of training is to ensure you know what you’re talking about; the second is to ensure you know how to communicate it to your athletes/clients.

You also don’t need a Ph.D. in Nutrition to work with most athletes. They may be elite in their sport, but they often reach that level in spite of their diets. I have found that my knowledge of nutrition and eating habits is often far above what is required to assist my athletes. For example, I have only had to refer out two people in the last five years.

2. Ask Questions

As I just mentioned, most athletes don’t know what they don’t know. So, it’s silly to expect them to come and ask me about how much protein they should be eating or if Pop-Tarts are really the best breakfast for them. Athletes (especially at the university level) live by an “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” mentality—so you need to show them that what they’re doing is broken (if it is). This can take many forms, but some options are:

- Weekly nutrition tips (how much protein to eat, why your body needs carbs).

- Social media posts or sharing others’ content.

- Asking athletes what they had for breakfast/lunch/dinner that day.

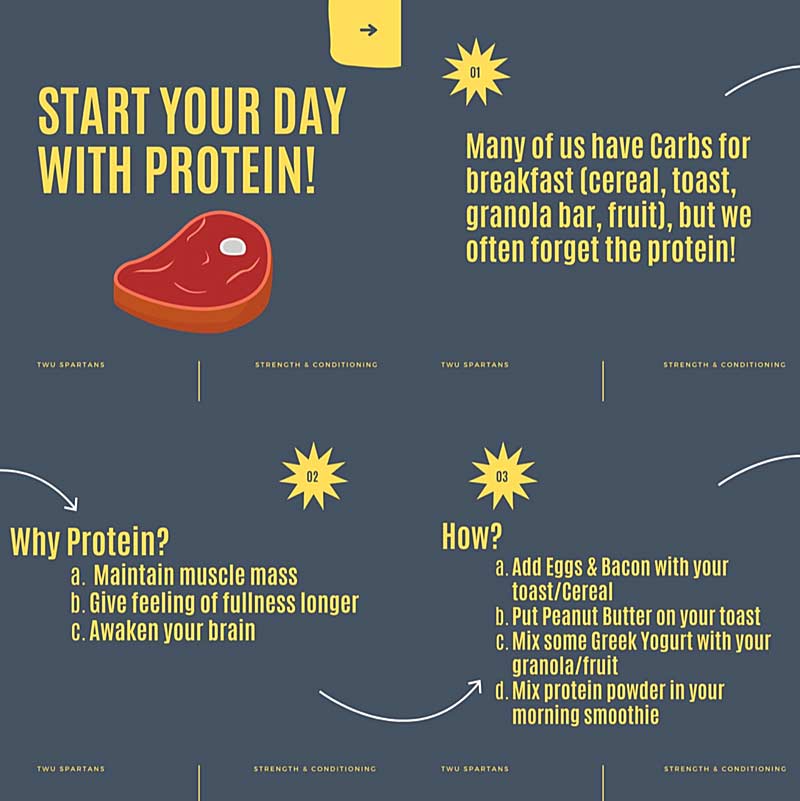

The main thing you’re trying to do is start a conversation and get them thinking about their eating habits. Once again, most athletes believe that the chicken in their salad at lunch is good enough because “Yeah, I ate protein today,” but they don’t understand how much they need. I have found that after doing a tip of the week on something like “Start Your Day with Protein!” (see image above), the lights turn on, and the questions flow in because you now showed them that what they’re doing is broken, and they need to fix it.

For example…

Q: How much protein should I have at breakfast?

A: Aim for 20 grams to start your day. But some is better than none!

Q: What if I don’t eat breakfast?

A: Then I recommend you start. It doesn’t have to be anything big (e.g., bacon and eggs); just try eating something, and we can build on that.

Q: Is cereal a good source of protein?

A: Most cereals are not. Some, however, (like Vector) do have a decent amount of protein—so if you add 1–2 cups of milk, you have a decent, protein-filled breakfast. Otherwise, you can still have your cereal (e.g., Cheerios, Corn Flakes), but I recommend adding another protein-rich food such as Greek yogurt, a couple of eggs, or a scoop of peanut butter.

3. Food Logs

Another interactive thing I have found to be successful is asking athletes to complete a two-day food log: one weekday (Mon–Fri) and one weekend day (Sat/Sun). That way, as a coach, you can get a sense of what they eat on a typical day. This is huge, as most athletes I speak with about their eating say, “I eat pretty healthy.” Okay, what is “pretty healthy” to you? As I have found out, it can range from not eating any processed sugar at all to only eating fast food two meals a day instead of all three meals, like some people they know.

Getting athletes to complete a food log allows you to see what they eat and give specific recommendations instead of shooting in the dark with general tips, says @chergott94. Share on XGetting athletes to complete a food log (as shown below) allows you to see what they eat and give specific recommendations instead of shooting in the dark with general tips like “eat breakfast,” “drink more water,” and “eat more protein” (even though those alone would cover about 80% of the issues…). An additional benefit for the athlete is that having them write down everything they consume in a day (food and drink) allows them to see their whole “diet” in front of their eyes, which can often help them realize the changes they need to make on their own. (“Oh, I should stop eating a box of cookies at midnight,” or “I should eat more for lunch before training.”)

4. Be Available

One of the best things I did was set a “Nutrition Office Hour” each week. Weekly, I send out the link to sign up for a 15-minute block during this hour. I believe this is crucial, as most people are not comfortable opening up about how they want to lose weight in front of a large group after their team training session. This gives them a more intimate setting to do so.

This one-on-one format also ensures they have your undivided attention instead of you trying to watch athletes finish their lifts while contemplating how to tell this athlete that they shouldn’t go Keto. Some weeks I don’t have anyone signed up, but other weeks people couldn’t sign up because it was booked. I have found that if they know you will have a slot each week, there will be times for them eventually. And if it really is important, they will wait until there is a slot.

5. Follow-Up

Following up is something I have recently started to get better at. After giving tips and meeting with athletes about their eating, it is important to follow up and make sure they are actually doing it. I have recommended to most athletes who sign up for my office hour for them to sign up again in a couple of weeks so we can go over their progress…but that rarely happens.

After giving tips and meeting with athletes about their eating, it’s important to follow up and make sure they’re actually doing it, says @chergott94. Share on XAs a coach, it is important for you to follow up with them to make sure they are doing what you planned together and see if it is working. This could be a quick email or, after a lift, just asking, “How are your eating habits coming along?” This may open a can of worms for you to deal with, so be ready to hear all the excuses in the world as to why they couldn’t eat breakfast this week.

But the follow-up is crucial so they know you truly care, you are holding them accountable, and you are with them for the long haul that most nutrition and eating journeys are. I keep a list of all the athletes I have met or chatted with in this area and reach out to them at least once a semester to see if I can help with their next step (if they have one).

Keep the Hat Light

Again, I want to clarify that I am not implying registered dietitians or sports nutritionists are not valuable members of a high-performance staff or that you shouldn’t implore your administration to hire them. But we all know that budgets are tight, and those roles (among many others) often fall to us. This is kind of crazy when you think about it because everyone eats multiple times a day, and we then have no one in charge of what athletes put in their bodies to fuel the rest of their day/performance/recovery.

So, if you are going to put on that hat, it is essential to be prepared so you can actually help your athletes and be an asset to your department without adding too much extra load to your own demanding schedule. The tips I outlined above take very little extra time (aside from studying for the certification exam). The others (tips, social media, office hours, follow-ups) take me an extra two hours a week (with one of those being my office hour), so, not a ton more work for a ton of payoff.

Peace. Gains.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF