With various sports finding ways to play and practice year-round, volleyball continues to drive up practice and tournament demands every year. For a high school volleyball athlete, school season leads right into club after a short break, with club leading into a break of 1–2 months before summer training for school season starts back up again. Add in sand volleyball, which takes place throughout various times of the year, and you get an athlete who is susceptible to overuse injuries and overall burnout. If you’re looking to plan a traditional “off-season,” you’ll find minimal time to reap the benefits and end up leaving potential gains on the table—so finding a more dynamic system ready for anything is the better option.

A good program for an athlete playing so much of the same sport will need to find the balance between performance and health. Share on XA good program for an athlete playing so much of the same sport will need to find the balance between performance and health. Chasing gains in the weight room with poorly timed and inappropriate methods can build up too much fatigue for optimal volleyball performance, but too much “playing it safe” on the health side of the spectrum, and you can have detrained athletes who won’t see any progress in developing physical outputs.

I’m in the fortunate position to train volleyball players throughout the year and have had zero long-term injuries and achieved numerous PRs on our KPIs (key performance indicators, or things we want to set records in) throughout this past school and club season. Three things have stuck out to me that could help others if they find themselves training high school volleyball athletes.

1. Isometric/Eccentric Methods Are Healthy Add-ins

Unless you somehow don’t have Instagram or X or just haven’t read up on trends within strength and conditioning, you already know about the benefits eccentric and isometric tempo training can have for an athlete. In short, eccentric training is the resisted lengthening of the muscle, and isometric training is producing force where a muscle’s length isn’t changing. Performance benefits from these methods are well known, with eccentric strength always being higher than concentric strength for potential gains, as well as isometrics (primarily overcoming) being able to produce forces much higher than concentric lifting. These are great for a total body vision, but I will look at their use primarily for the lower body here.

Methods of each I prefer include:

Eccentric

- Overloaded eccentrics (80% +) (rarely used)

- Slow eccentrics (60%–75% of 1RM)

Isometric

- Overcoming (pushing against an unmoving object)

- Yielding (holding at various positions)

During competition, the lower body of a volleyball player is constantly asked to perform fast concentric actions in various ranges of motion: front row players jumping and landing constantly at the net, as well as back row players reaching low ranges at high speeds to meet the ball for defensive plays, have their hips, knees, and ankles constantly moving at high speeds to make plays. To get the balance the body likes, these methods will contrast the body’s explosive actions during a volleyball game with slower/yielding lifts that will drive performance on the court with a base of health from the weight room.

The soreness that eccentric training can cause is a well-known factor, and I know some coaches reading this have never considered eccentrics in season, for understandable reasons.

Muscle lengthening has been known to provoke strong delayed-onset muscle soreness and can be a fatiguing stimulus on the nervous system as well; however, I’ve been able to mitigate these effects with proper intensities and volumes (just like any exercise). The best scenario is having athletes who have experienced eccentric training, as their bodies will be ready for it.

Keeping slow eccentrics within the percentage ranges that are away from a maximal stimulus or choosing smaller isolation exercises instead of compound lifts has helped mitigate those effects in my athletes’ training. If it is a worry, then saving it for training periods without as much competition can be great as well, and using isometrics can carry a decent amount of the workload.

2. Know the Right Kind of Jumps to Attack

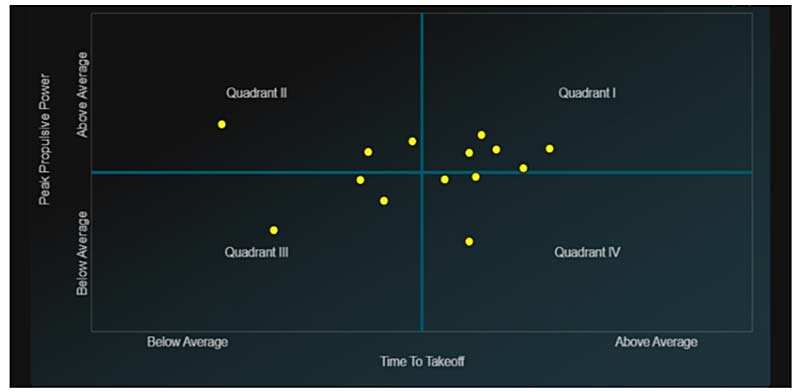

It can be very easy to refrain from the intensity of jumping with all the jumps that occur in practice and games, but again, if we hold back too much, we cannot grow. Tyler Friedrich’s article, “An Alternative Way to Think about Plyometric Training for Women’s Volleyball,” sheds light on the fact that most of the jumps within practice and games don’t end up being near any personal bests as far as jump heights go.

If we hold back too much, we cannot grow. Share on XThat article was for college players who are among the top female jumpers in the world—so, in the case of high school players who, on average, do not reach that level of height, the jumps can have even less of a nervous system stimulus than what Friedrich highlighted. This is not to downplay the fatigue that comes with jumps happening in practice and games, but when looking to keep plyometric and jump training in the program, this data can help us pick our training methods.

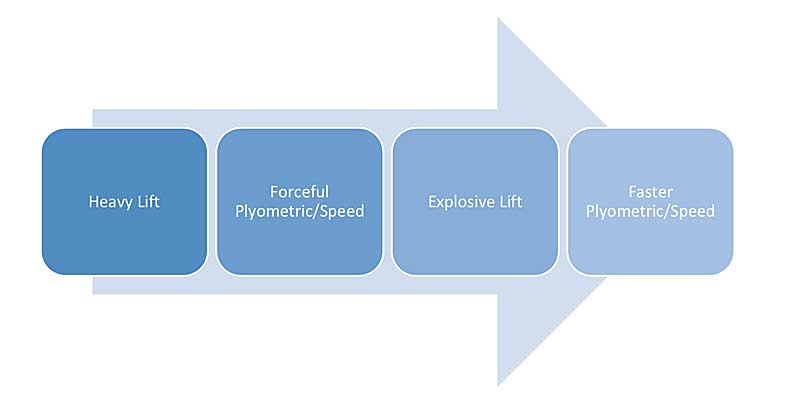

I put this fatigue into an “extensive” category with lots of quick, medium-/low-intensity ground contacts that can wear on the feet, ankles, knees, and entire lower body complex. Filling the extensive bucket means the intensive bucket can have more attention put on it. Lower rep sets for maximum intensity can get the strong nervous system drive we want to tap into high-threshold motor units. This doesn’t mean I don’t plan extensive jump work, as I try to keep in all important qualities all the time, but we know where to put our higher workloads from the data.

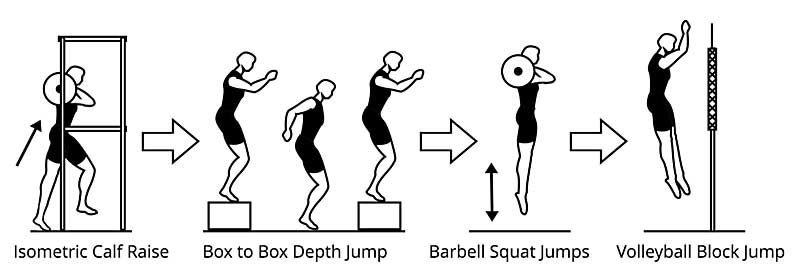

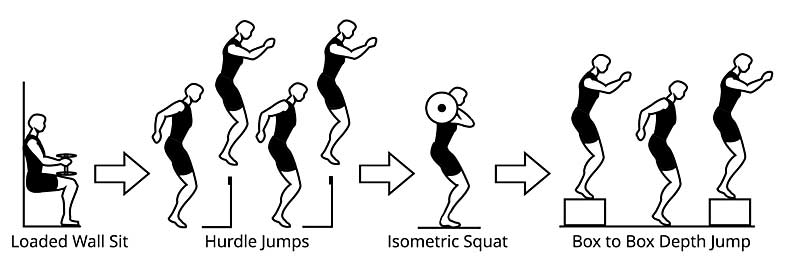

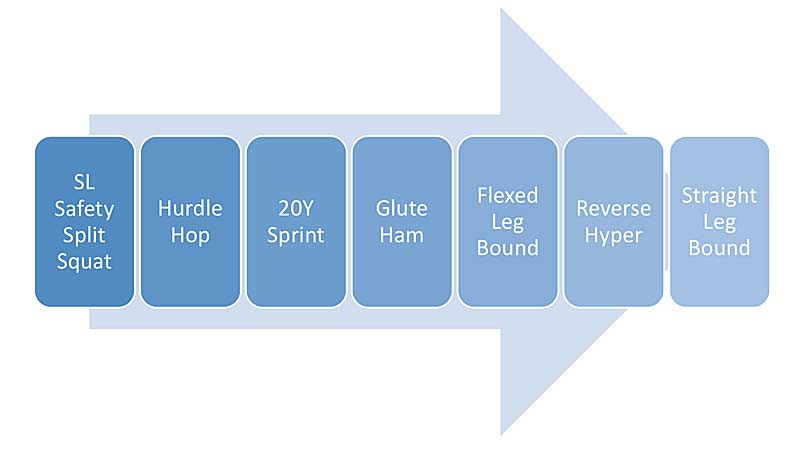

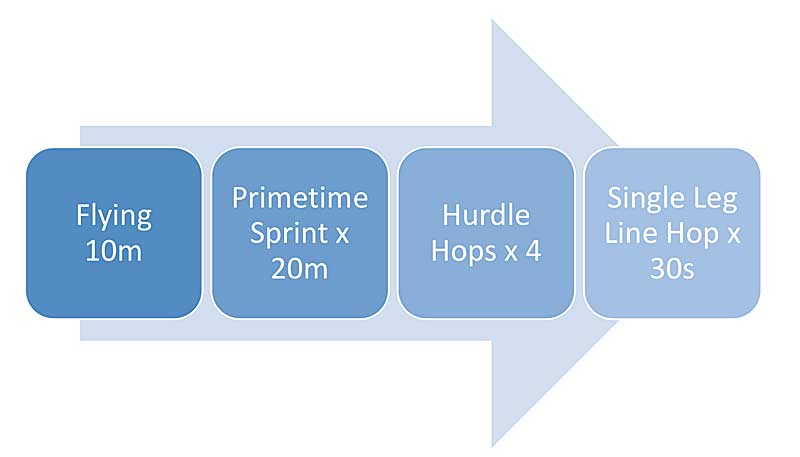

Variations of jumps/plyos I like include:

- Resisted jumps (dumbbell, hex bar, barbell, band-resisted)

- Seated jumps for maximal height/distance,

- Broad jumps

- Depth/Drop jumps

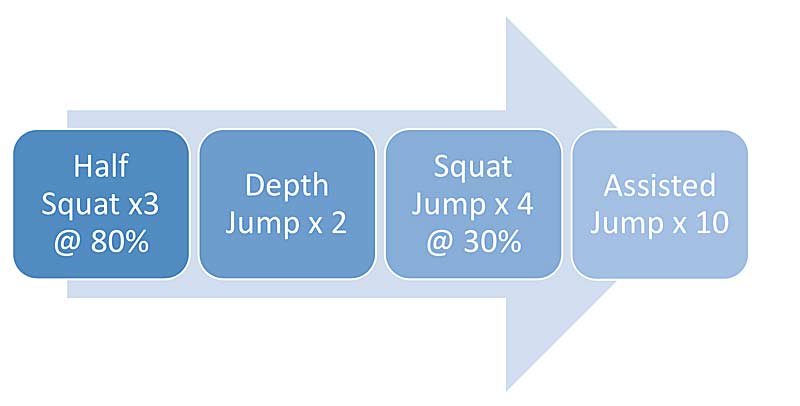

Having tools like a jump mat or hurdles for the athletes to try and jump over is key to getting output with direct feedback of jump heights being known right away and helping create a fun, competitive environment. Intent is the key to any training program’s success, and when I can get it, I will go after it. Reps and sets can vary, but 2–4 sets of 3–5 reps for these types of jumps has been a good sweet spot and can be more with an athlete who has a younger training age.

A few other notes:

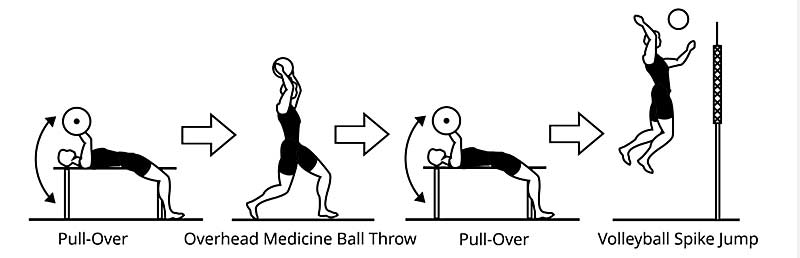

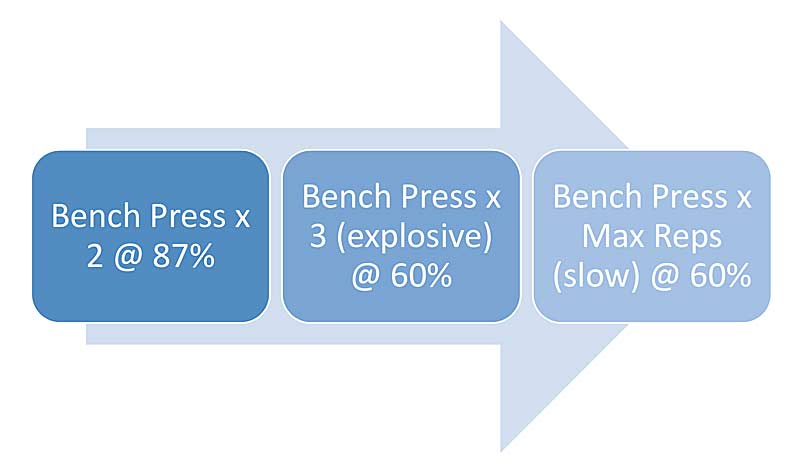

- Complex training is a great method for potentiating jumps while conserving training time. Heavier lifts/jumps paired with bodyweight/unweighted jumps can be an effective addition.

- Olympic lifting has had a great transfer to jumping for my athletes on their own and in complexes. (I will not waste my time arguing about whether Olympic lifts should be done.)

- Depth/drop jumps and landings are also a strong stimulus on the lower body and, along with all the practice and game jumps, can build fatigue fast. However, these allow the athletes to adapt to landings far higher than their current jumps give them and won’t be a problem when timed and dosed correctly.

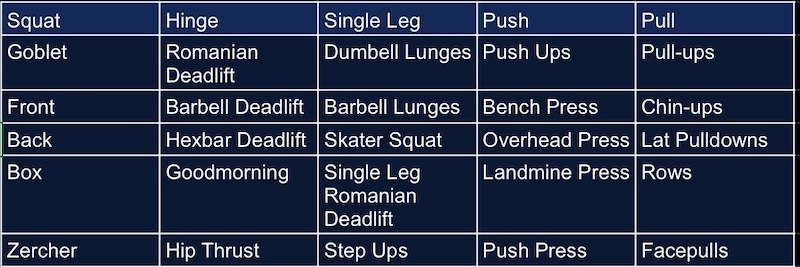

3. Build a Strong Base with Variation

A base of physical literacy within core movement patterns is one of the first things I try to increase in an athlete when they begin training with me. The core themes of squatting, hinging, single-leg movement, and upper pushing and pulling will build the movement toolbox that will help them develop over time. When the athletes are first learning, I like to slow-cook their process with foundational movements that can get the point of each across. For example, goblet squats are almost always the first squatting movement I teach, and the athlete will stick with that for two blocks of a couple of weeks. After a good time developing the correct technique and learning the “why” behind the squat, we can move to a barbell.

New athletes to the weight room can get away with making progress from this for a long time, so there isn’t the need to vary the movement approach too much. But I have athletes who have been training for years, and for a lot of them, the weight room is an outlet from the sport of volleyball itself. It offers the physical fulfillment they’re used to in something different than the sport they play at least twice a week, almost year-round. So, for the experienced athlete, I need to look into how I can keep building upon the physical abilities they’ve gained in the weight room and give them something they want to push toward without things becoming less engaging.

In addition to keeping intrigue within the program, variation widens the base of the athletes’ preparedness. Share on XIn addition to keeping intrigue within the program, variation widens the base of the athletes’ preparedness. By keeping the core movement patterns within your program but also switching variations at a good pace, you’re building a base of physical GPP with new tissue developed and movement literacy learned, but also working the fundamentals of the pattern your system has. There are different ways coaches like to teach their squatting movements, but in my system, I’m hoping my athletes can transition front squats to back squats (and vice versa) from one training block to the next. Our squatting pattern is still being trained, but the slightly different physiological benefits these movements have from one another can be just enough to create a change for that athlete.

Louie Simmons was the first to bring the idea of true variation to training with his conjugate method system, looking to avoid the law of accommodation with his powerlifters. Stating that the body will adjust to the stimulus that is continuously put on it, his ideas of max effort variations constantly changing helped him dominate the geared powerlifting world for years.

With all that being said, my volleyball players are the furthest thing from geared powerlifters, so squat suits and bench shirts will not be needed. However, switching between movements within our core movement patterns contributes to the athletes’ overall growth without feeling repetitive and becoming accommodated for no growth. A time frame of 3–4 weeks per training block is the sweet spot to have enough time to squeeze all we can out of those variations without overstaying our welcome.

As for which movements to pick, having a good understanding of what athletes know can guide the process. When there is a stretch of a couple of weeks where the athlete has no tournaments, introducing a brand-new movement can help bring new growth. When we know we are coming to a volleyball-packed couple of weeks, switching to a variation that we know the athlete has literacy with is the better option, considering that brand-new movements can be more fatiguing on the body.

When there is a stretch of a couple of weeks where the athlete has no tournaments, introducing a brand-new movement can help bring new growth. Share on XRemember, just like the difference between medicine and poison being dosage, the same goes for methods of training. Knowing how much of something to do and when to do it is incredibly important when trying to push athletic development within a competition period.

While this seems like a concept better suited for the more experienced athlete, early variations for accessory movements can be introduced for beginners very well. Even if your goblet squats and push-ups stay as staple movements for a while, making minor adjustments to your lower-tier accessories can go a long way. New core work every block or switching from DB to cable rows keeps things surprisingly fresh for someone new to the iron game.

Along with the exercises used, variation of the movement planes and where you move within space is also important. While every sport has its bias and specific needs, the chaos on the field of play can never be completely accounted for. In the case of volleyball, athletes practice their skill sets for various jumping, blocking, setting, and passing scenarios; awkward setups and reactions to a play can lead the body into positions it’s never seen before, which can ultimately lead to injury. If we are going to do our best to “bulletproof” these athletes, we need to leave no stone unturned.

To fill this need, I have my athletes cover a variety of resistance and movement exercises in the three planes of motion: the sagittal (forward and backward movement), the coronal (lateral), and the transverse (rotational movement). Within these planes, we not only want to build tissue within the primary movers but also work to increase movement speeds and the ability to be fluent within those spaces. Grouping movements for the planes, I look to label them as either “resistance” or “movement” exercises.

These are general terms, but you can get the idea. Examples of each can look like:

- Sagittal: forward or reverse lunges for resistance, linear sprints for movement.

- Coronal: lateral lunges for resistance, shuffling for movement.

- Transverse: Pallof press with rotation for resistance, medicine ball step-in throws for movement.

Challenging these plans with new variations, speeds, and tempos allows for a full toolbox of resilient tissue to be built. The more we can build through variability, the higher the chances that an “unseen” position to the body isn’t as unseen as we think, and we will not only survive the position but thrive in it.

Improve Performance While Maintaining Health

We are fighting the battle of fatigue when it comes to training athletes who always have competition going on. With volleyball, I’ve found that there’s always the attraction to playing it safe and getting these players through their season—but there’s too much potential in what they could do to have them skip their training for weeks on end during a competition period. Health is always first and foremost for these athletes and will be considered before anything else, but I believe we can achieve a solid increase in performance throughout their careers while keeping them on the court happy, healthy, and playing the game they love.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Full disclosure, I was born and raised in Nebraska and had the privilege of interning at the University of Nebraska, learning from Boyd Epley and Mike Arthur. I did not choose this program out of nostalgia or so that young coaches know their history. All of those are good aftereffects, though. I chose this program because, as Mike Arthur told me one day on the floor, “I know my old program might be outdated, but it’s better than half the programs I see nowadays.”

Full disclosure, I was born and raised in Nebraska and had the privilege of interning at the University of Nebraska, learning from Boyd Epley and Mike Arthur. I did not choose this program out of nostalgia or so that young coaches know their history. All of those are good aftereffects, though. I chose this program because, as Mike Arthur told me one day on the floor, “I know my old program might be outdated, but it’s better than half the programs I see nowadays.”

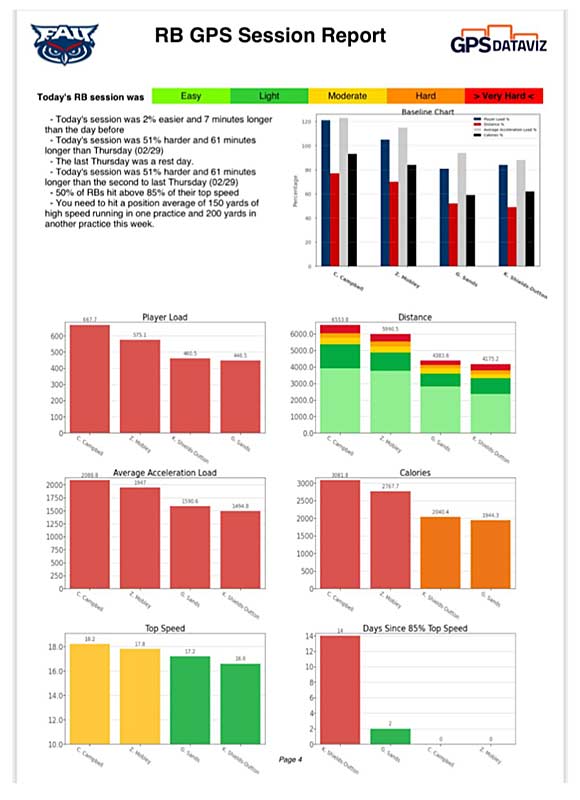

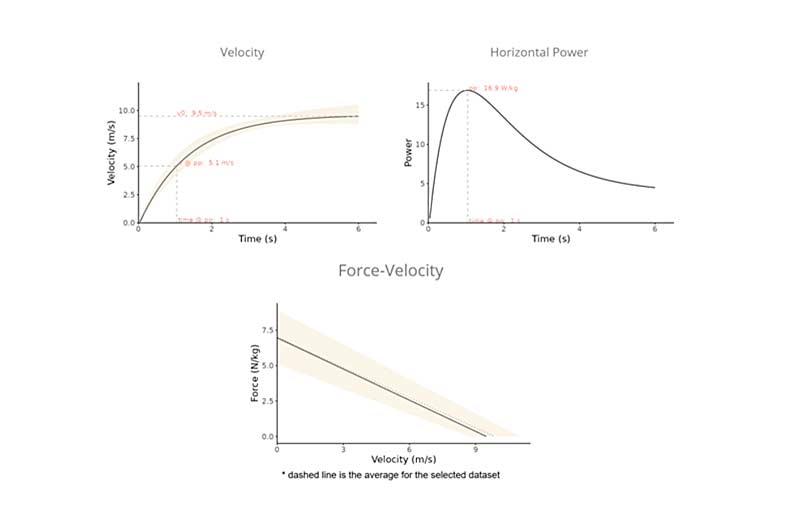

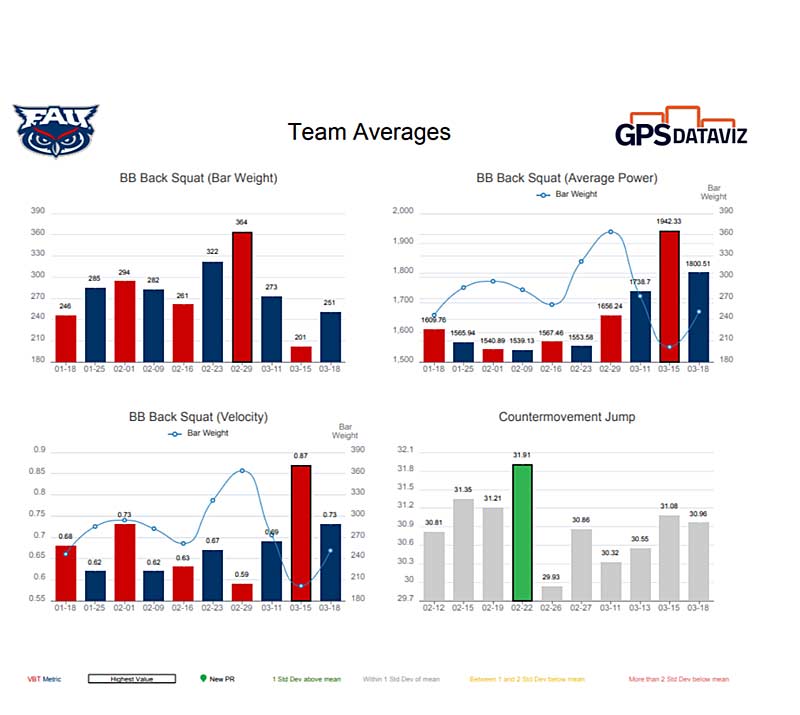

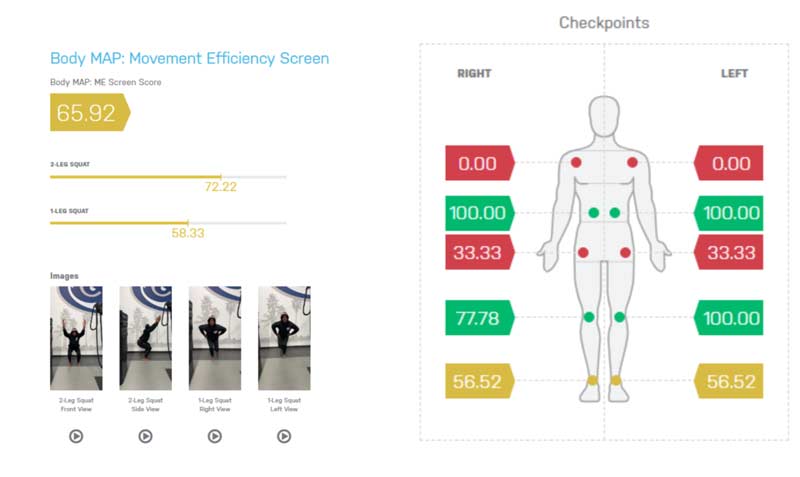

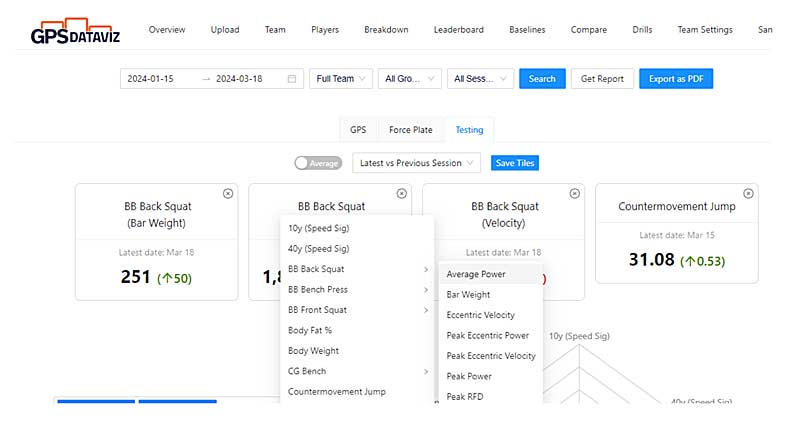

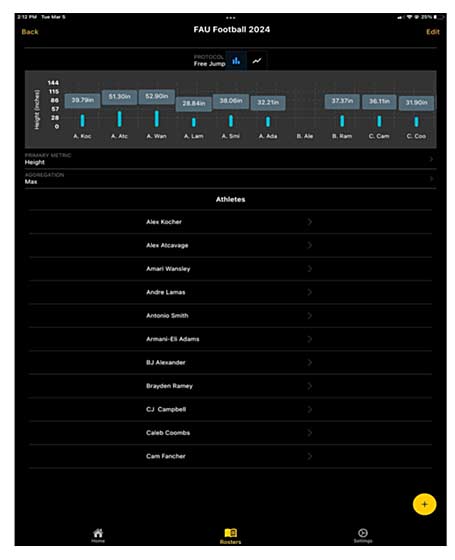

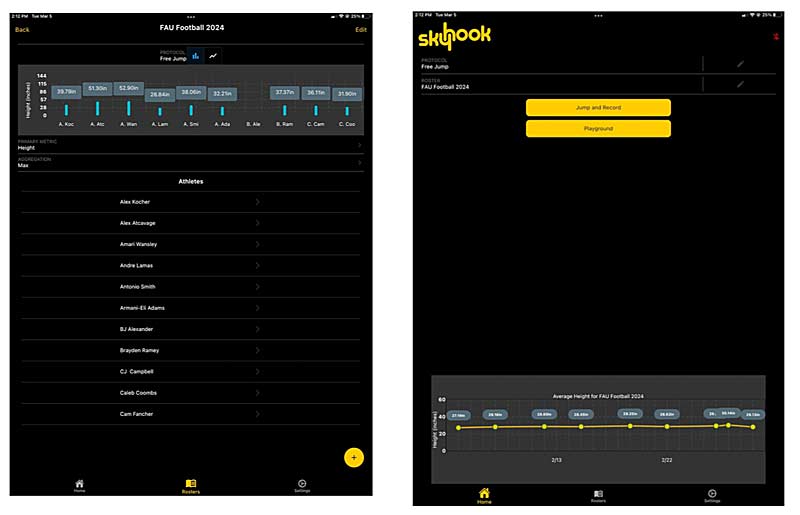

Zackary Ceci started his career as an intern at FAU in 2022. He also spent time at the University of Tennessee as an intern and even in the private sector at “Triple F” in Knoxville, Tennessee. Ceci was hired back on staff to FAU in the summer of 2023, and over time at these various stops, he gained knowledge in advanced technologies such as: Elite Form, Catapult, Kinovea,

Zackary Ceci started his career as an intern at FAU in 2022. He also spent time at the University of Tennessee as an intern and even in the private sector at “Triple F” in Knoxville, Tennessee. Ceci was hired back on staff to FAU in the summer of 2023, and over time at these various stops, he gained knowledge in advanced technologies such as: Elite Form, Catapult, Kinovea,  Robert Marco played four years of football at Washburn University, followed by a brief stint playing professionally from 2018–2019. Marco began his coaching career as a volunteer strength and conditioning assistant at the University of Kansas in 2020 and had his first paid opportunity at FAU with Coach Joey Guarascio in 2021. He then took another assistant job opportunity at Liberty University and Coach Dominic Studzinski in 2022. Following the 2022 season, Marco was brought back to FAU as Associate Head Strength Coach by Coach Guarascio.

Robert Marco played four years of football at Washburn University, followed by a brief stint playing professionally from 2018–2019. Marco began his coaching career as a volunteer strength and conditioning assistant at the University of Kansas in 2020 and had his first paid opportunity at FAU with Coach Joey Guarascio in 2021. He then took another assistant job opportunity at Liberty University and Coach Dominic Studzinski in 2022. Following the 2022 season, Marco was brought back to FAU as Associate Head Strength Coach by Coach Guarascio.