[mashshare]

Injuries are inevitable in sport. Athletes may lose weeks, months, or even years of playing based on the severity of an injury. In some drastic cases, injuries may even force early retirement. Both athletes and organizations potentially lose significant value over time due to injuries. Athletes may lose out on lucrative contract extensions or even on contracts altogether. Sport organizations are no different. In the short term, organizations get no return on their investment when the athlete is sidelined. In the long run, they may lose money on their investment due to reduced trade or sale value.

Lately, I’ve been seeing more and more cases of chronic tendinopathy keeping players away from their sport. This might be because this is actually becoming a more frequent issue and injury, possibly because of increased diagnosis from medical professionals due to more understanding of and research on the subject, or it may just be me now noticing how many cases of this type of injury there actually are. If tendinopathies are becoming a more frequent diagnosis among athletes, it begs the question of whether we’re still in the dark ages when it comes to various tendinopathies, a tendon’s role in performance, and the systems-based approach behind the rehabilitation of tendons.

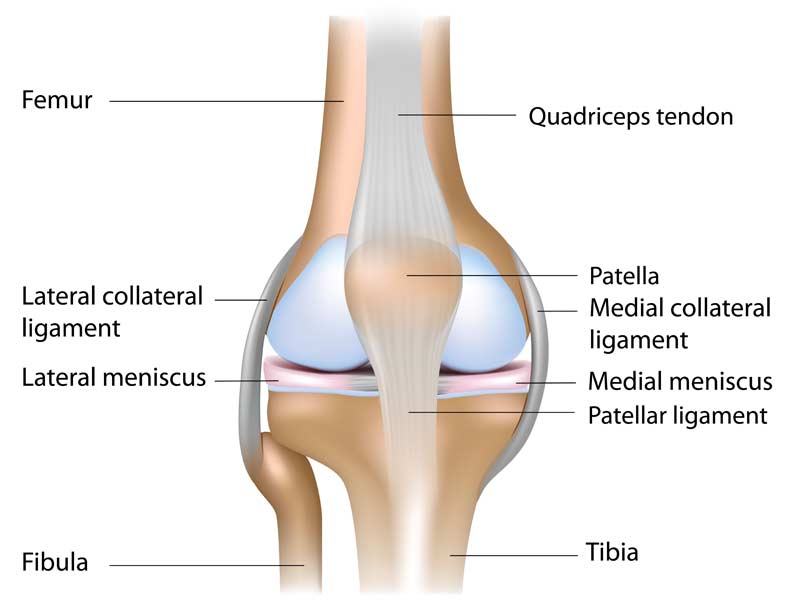

If tendinopathies are a more frequent diagnosis, it begs the question of whether we’re still in the dark ages when it comes to the systems-based approach behind the rehabilitation of tendons. Share on XTendons connect muscle to bone and are responsible for storing and releasing energy. A tendon can be thought of as a steel spring, in that the faster and higher a degree of stretch the steel spring experiences, the more energy it will release. Like many other structures in the body, tendons also have a load capacity. The patellar tendon is not unlike other tendons in that it also has a capacity for load that is individual to the athlete.

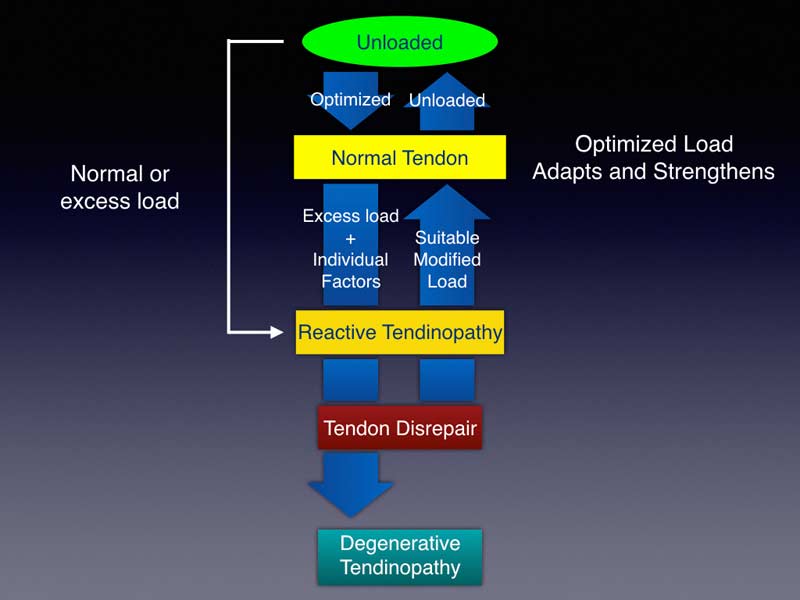

After loading the tendon with activities such as jumping, sprinting, and changing direction, the tendon is at a reduced capacity. In a normal tendon, remodeling will occur, and the tendon will return back to full capacity (and potentially to greater capacity) as long as the stress does not greatly exceed the tendon’s current capacity. When we place stress on the tendon far beyond the tendon’s current capacity, either through a large single session stimulus or cumulative stress from multi-session stimuli without sufficient recovery, it creates a change in the tendon’s properties that prohibits it from returning to its normal state. This is generally known as the reactive state or the state of disrepair, as seen in figure 1.

In this reactive or disrepair state, tenocytes—cells located within the tendon that assist in collagen type I synthesis—no longer function normally.2,3 This collagen is critical to the tendon, as it largely dictates the structure and strength of the tendon since it makes up nearly 80% of the dry mass of the tendon4. Without proper tenocyte function and collagen synthesis, the tendon’s capacity may be reduced. The further the tendon goes into the disrepair state and the longer it stays there, the harder it may be to bring the tendon back to a pain-free or normal state.

There has been some notable time missed due to injuries related to tendinopathy and suspected tendinopathy. Patellar tendinopathy is not only present in jumpers, although this injury is sometimes referred to as “jumper’s knee.” It can also be present in any sport that consistently requires the athlete to load the tendon with high forces with insufficient time for the tendon to remodel. A few recent examples of this are:

- Earlier this year, U.S Men’s National Team goalkeeper Zack Steffen missed games due to patellar tendinopathy.

- Patriots receiver Julian Edelman’s current knee injury is speculated to be patellar tendinopathy or a patellar tendon tear that stemmed from tendinopathy.

- LA Clippers superstar Kawhi Leonard has been dealing with ongoing patellar tendinopathy, which has forced the Clippers to rest him significantly this season.

Tendinopathy can be a crushing blow to an athlete. Depending on the severity of the tendinopathy, athletes may lose considerable time because of pain and injury. Additionally, at times the tendon can continue to degrade, potentially causing a tear or rupture that may force retirement from the sport altogether.

Some injuries are arguably more controllable than others. Tendinopathies are one of those injuries that, if managed well, can almost become a non-issue. If managed poorly, they can turn into multimillion-dollar disasters. Many times, tears and ruptures occur because of degradation of the tendon over time. Malliaras et al. mentions that a tendon rupture in absence of systemic disease is rare.5 With this in mind, we could conclude that some, if not many, tendon tears and ruptures could be avoided if managed well early in the process.

We have a player who has had ongoing patellar tendinopathy for the previous few seasons. It got progressively worse over this past season—so much so that he had to change his kicking technique to be able to tolerate the pain. Since it wasn’t really an option to take the time needed during the season, we decided to work on it this off-season. The following is the general plan we used based on concepts from the current research on patellar tendinopathy and speaking with other coaches like John Evans, who has worked with many athletes with various tendinopathies.

Stage 1: Rest

Duration: 14 days

Rest sometimes gets criticized in the performance realm because the thought is that if you’re injured, you can and should always do something. While I agree with this sentiment most of the time, in this case he came off of a nine-month season with increasing pain in the patella tendon in the last two months of the season. Two weeks off would most likely do more good than harm, in this case.

If you find you don’t have the luxury of time, you could very well forego resting and move right into Stage 2, especially if you’re in-season, and a timeline for return is important. For us, resting was beneficial from a mental and physical standpoint.

Stage 2: Load the spring with no change in length

Duration: 14 days

Weight room: 6 sessions (isometrics were also performed every day)

Goalkeeper-specific: 6 sessions (paired on same day as weight room)

Focus: Reduction of pain, structural changes, low load tolerance

Restrictions: No energy storage and release activities in goalkeeper-specific training.

Isometric exercises are characterized by creating tension with no change in length to the musculotendon unit. Isometrics have been getting a lot of attention lately for their ability to reduce pain in patellar tendinopathy. Rio et al. showed that isometric exercise was more effective than isotonic exercise at reducing pain post respective exercise.6 Out of the six participants in the isometric group, all six athletes’ pain levels dropped to either 1 or 0 immediately after exercise and remained at low pain levels for 45 minutes after the exercise intervention. This was not the case for the isotonic exercise group.

Another benefit of isometrics is that they’ve been shown to increase strength by nearly 20% post-exercise.6 This could potentially be due to the reduced pain experienced and/or higher motor unit activation after the isometric exercise is completed.

The characteristics that make isometrics good for managing pain during competition periods (reduced pain and increased strength) also make the exercise a prime choice for the early stage rehab of patellar tendinopathy. Since the load on the tendon is quite low, we performed isometrics frequently. This was, in theory, to allow the tendon to be able to better accept load later on in the process and also to start to attack visible atrophy that had occurred over the course of the last couple of seasons.

The characteristics that make isometrics good for managing pain during competition periods also make them a prime choice for early stage rehab of patellar tendinopathy, says @john_r_grace. Share on XAfter the first two weeks, we had 24-hour post-exercise ratings of 0–1 and the very occasional 2 (pain-free to relatively pain-free).

While we accomplished the goal for this phase of the tendon to remain relatively pain-free, this is only the initial goal. We had a long way to go for the tendon to be able to tolerate basic stretch-shortening cycle (SSC) type loading, which is the bulk of what this athlete will see when he returns to sport. The idea of being pain-free is great, but it’s not that useful when it comes at the expense of reduced performance. On top of potentially reduced performance, if the tendon returns to a pain-free state and the athlete returns to full training from this stage, the tendon will most likely return back to square one in the reactive stage because the underlying capacity of the tendon has most likely remained unchanged.

Stage 3: Load the spring with slow changes in length

Duration: 17 days

Weight room: 7 sessions (continue to perform isometrics on off days)

Goalkeeper-specific: 7 sessions (paired on same day as weight room)

Focus: Strength, hypertrophy, higher load tolerance

Restrictions: No energy storage and release activities in goalkeeper-specific training.

Due to previous research7–9, various eccentric exercises have been long thought of as the answer to patellar tendinopathy, and practitioners sometimes view this as the place to begin with this injury. While eccentric exercises can be part of the answer, depending on the severity of the tendinopathy, even slow eccentrics may be too aggressive for some cases. This is the reason this was not our first stage of rehabilitation.

While eccentric exercises can be part of the answer, depending on the severity of the tendinopathy, even slow eccentrics may be too aggressive for some cases, says @john_r_grace. Share on XIn this stage, we want to not only perform the eccentric muscle action, but the concentric action of the exercise as well. When we performed traditional strength exercises, we wanted to implement them in a way that limits the involvement of the SSC as much as possible. Strength training in the traditional sense (squatting, lunging, etc.) does not rely on the SSC to a great degree, but in some exercises you may see an athlete use the SSC to lift more weight or move a weight faster (for example “bouncing” out of a squat).

We structured our weight room work in this stage largely around squatting. It’s important to understand that the stimulus in this stage could most likely come from many lower body strength activities (keeping in mind the degree of knee flexion that is tolerable for the athlete at this time). It’s more the concept of the progressive load we’re attempting to provide to the tendon than the exercise itself, though squatting lends itself well to goalkeepers in that it is a nice prerequisite for high levels of force production in bilateral jumping activities.

Another reason squatting was a good fit in this case is that, according to the athlete, he has not been able to squat pain-free in more than two years. Performing this exercise pain-free for the first time in a few seasons helped him see the light at the end of the tunnel and allowed him to have more confidence in the current progression.

Initially, we chose to squat to a box slightly above parallel so as to put the knee in squatting angles that were tolerable for the tendon, but also to take away any real chance of using the SSC as most proficient squatters do. After some comfort was reestablished with the movement a few sessions in, we dropped the box a few inches to a parallel squat with similar execution to the movement. We progressed in a relatively linear fashion to a 1.4–1.5x bodyweight squat.

Within this stage, pain was consistently nonexistent, and daily activities like longer car rides and walking downstairs—activities that were once bothersome—were no longer even a thought in his mind. This is a win because we now have more confidence that we’ve moved the needle on the tendon’s capacity.

Stage 4: Load the spring with fast changes in length

Duration: 31 days (and counting)

Weight room: 14 sessions

Goalkeeper-specific: 20 sessions

Focus: Energy storage and release tolerance

Restrictions: Minimal jumping/long kicking on field for first two weeks. After first two weeks, progress to unaltered jumping and long kicking.

To preface, we are currently working through this stage and will continue to work in this stage for some time, since this stage essentially morphs into a maintenance stage where our goal is to continue to develop and maintain capacity. Since the tendon’s role is to store and release energy, this is the most important stage to get right. As I said earlier, pain-free doesn’t matter unless we can achieve performance equal to or beyond what was previously established.

The early focus in this stage was on being able to tolerate relatively faster eccentric loading to the patellar tendon. We performed depth drops once a week, pairing this day with the most intense day on the field. Along with this, we performed stage 2 and stage 3 exercises within the week as well.

The athlete performed depth drops at a moderate height relative to his capabilities, and we progressed intensity over a few weeks. Once drop height roughly reached the athlete’s maximum jump height, we progressed to depth jumps and added a second day of jumping with loaded discrete CMJs. On those intense days we also continued to maintain stage 2 exercises. At this point in the process we had two relatively intense days and one relatively lighter day in the weight room, and we will continue this schedule assuming everything goes well.

In the goalkeeper training on field, we pulled off all major restrictions. We’ve progressed to kicking ~20 goal kicks in a session once a week. While he does still have a very slight amount of discomfort with this volume, that discomfort dissipates by the next morning, which is one of the hallmark characteristics of a “stable” tendon.5 In theory, stressing the tendon in such a way that it recovers normally should continually increase the tendon capacity over time as tendon remodeling is a continuous process that is more efficient in tendons exposed to high stress.10

In theory, stressing the tendon in such a way that it recovers normally should continually increase the tendon capacity over time, says @john_r_grace. Share on XIdeally, if things go as planned with no major setbacks, our location on the rehab-performance continuum will continue toward a greater focus on improving global capacities and performance and continue to move slightly away from rehabilitation. With regard to progressing plyometric intensities and volumes, we’d like to move toward loaded continuous CMJs (~20–30% athlete back squat maximum) and hurdle hop types of activities while maintaining the lower body strength work. On the field, we expect the tendon tolerance to be high enough to sustain five training sessions per week, which may require 2–3 of those sessions to be very intense to closely match the type of training the athlete would see in a pre-season setting.

Further Considerations in Managing Tendinopathy

In addition to what I’ve already discussed, there are other influences on patellar tendinopathy pain and management.

Pharmaceutical and Over-the-Counter Drugs

The use of anti-inflammatories and pain meds may create an environment where the tendon pain decreases but the capacity and ability for the tendon to accept load remains unchanged. In this case, the tendon may continue to degrade over time with no symptoms, which may lead to tears and ruptures.

On top of this, opinion has moved away from inflammation being part of the tendinopathy process.11 Other than for potential pain management, there might not actually be any need for NSAIDs or other medication to begin with.

With regard to this athlete, he only used anti-inflammatory and pain drugs on a few very rare occasions during the in-season to combat pain associated with the tendinopathy. Luckily, this athlete did not want to rely on these types of pharmaceuticals to get him through the season. He didn’t use prescription or over-the-counter drugs during this off-season training plan.

Supplementation

Collagen peptide supplementation has been proposed to assist in rehabilitation of tendon-related issues as participants responded positively to pain and performance-related markers.12 Along with this, vitamin C has also shown promise in the ability to enhance collagen synthesis.13 Our registered dietician on staff recommends taking these two supplements together for optimal uptake.

The athlete took collagen and vitamin C either pre-field training or pre-weight-room training. While I did not control the dosage or administer the supplements, the athlete made his own supplement drink prior to training based on previous education with a registered dietician.

Rehabilitation Is Personal

This realm, as with many, has a long way to go for full understanding of the topic, but researchers such as Jill Cook, Ebony Rio, and their colleagues are putting out some tremendous work that is practical and actionable in many sport settings. While the setup outlined above has worked for us up to this point, the time of year, the athlete’s previous training history, and the severity of their tendinopathy may dictate how much time you will need to spend on exercise selections and volume/intensity progressions in each stage.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

1. Rudavsky, Aliza, and Jill Cook. “Physiotherapy Management of Patellar Tendinopathy (Jumper’s Knee).” Journal of Physiotherapy. 60, no. 3 (September 2014): 122–29.

2. Huisman, Elise, Alex Lu, Robert G McCormack, and Alex Scott. “Enhanced Collagen Type I Synthesis by Human Tenocytes Subjected to Periodic in Vitro Mechanical Stimulation.” BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 15, no. 1 (December 2014): 386. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-15-386.

3. Cook, J L, E Rio, C R Purdam, and S I Docking. “Revisiting the Continuum Model of Tendon Pathology: What Is Its Merit in Clinical Practice and Research?” British Journal of Sports Medicine. 50, no. 19 (October 2016): 1187–91. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095422.

4. Kannus, P. “Structure of the Tendon Connective Tissue.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 10, no. 9. (July 2000): 312.

5. Malliaras, Peter, Jill Cook, Craig Purdam, and Ebonie Rio. “Patellar Tendinopathy: Clinical Diagnosis, Load Management, and Advice for Challenging Case Presentations.” Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 45, no. 11 (November 2015): 887–98.

6. Rio, Ebonie, Dawson Kidgell, Craig Purdam, Jamie Gaida, G Lorimer Moseley, Alan J Pearce, and Jill Cook. “Isometric Exercise Induces Analgesia and Reduces Inhibition in Patellar Tendinopathy.” British Journal of Sports Medicine. 49, no. 19 (October 2015): 1277–83.

7. Rutland, Marsha, Dennis O’Connell, Jean-Michel Brismée, Phil Sizer, Gail Apte, and Janelle O’Connell. “Evidence-Supported Rehabilitation of Patellar Tendinopathy,” n.d., 14.

8. Purdam, C R. “A Pilot Study of the Eccentric Decline Squat in the Management of Painful Chronic Patellar Tendinopathy.” British Journal of Sports Medicine. 38, no. 4 (August 1, 2004): 395–97.

9. Young, M A. “Eccentric Decline Squat Protocol Offers Superior Results at 12 Months Compared with Traditional Eccentric Protocol for Patellar Tendinopathy in Volleyball Players.” British Journal of Sports Medicine. 39, no. 2 (February 1, 2005): 102–5.

10. Zabrzyński, Jan, Agnieszka Zabrzyńska, and Dariusz Grzanka. “Tendinopathy – a Disease of Tendons.” n.d., 8.

11. Rees, J. D., A. M. Wilson, and R. L. Wolman. “Current Concepts in the Management of Tendon Disorders.” Rheumatology. 45, no. 5 (May 1, 2006): 508–21.

12. Praet, Stephan F.E., Craig R. Purdam, Marijke Welvaert, Nicole Vlahovich, Gregg Lovell, Louise M. Burke, Jamie E. Gaida, Silvia Manzanero, David Hughes, and Gordon Waddington. “Oral Supplementation of Specific Collagen Peptides Combined with Calf-Strengthening Exercises Enhances Function and Reduces Pain in Achilles Tendinopathy Patients.” Nutrients. 11, no. 1 (January 2, 2019): 76.

13.DePhillipo, Nicholas N., Zachary S. Aman, Mitchell I. Kennedy, J.P. Begley, Gilbert Moatshe, and Robert F. LaPrade. “Efficacy of Vitamin C Supplementation on Collagen Synthesis and Oxidative Stress After Musculoskeletal Injuries: A Systematic Review.” Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 6, no. 10 (October 2018): 232596711880454.