A coaching role is a teaching responsibility and we must understand that educating our athletes cannot be a passive or secondary behavior. Whether you work with young athletes or an adult population, those individuals have sought out the services of a coach in order to receive direction and guidance. And while there is an obvious tangible component to this (i.e., improving physical traits), there is also an underlying essence to what athletes expect from coaches: clarity and confidence.

Largely influenced by replicating a militaristic approach, for several decades the coaching industry had been misguided into believing that we needed to be the resident disciplinarian or authority figure within the sport or training setting. Fortunately, we are seemingly entering a transition point where the majority of us have seen the obvious shortcomings of this approach. Rather than meeting athletes with superiority and intimidation tactics, we need to recognize the importance of humanizing our relationship with our athletes. This doesn’t mean that we are without structure and professionalism; but there is a resounding difference between treating athletes like humans and soldiers at boot camp.

There is a resounding difference between treating athletes like humans and soldiers at boot camp, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XMost of this speaks for itself, but a lot of these steps are just taking more initiative with the intangibles we all know—making eye contact when athletes are speaking to you, listening attentively, being considerate of their input, and so forth. These are things that require no technical skill or credentialling but really solidify how to be a good human.

I’ve made countless adjustments to my coaching and perception of human performance over the years, but few things have been more influential than incorporating a designated movement literacy day and putting an emphasis on developing or repairing the athlete’s relationship with training.

In this article, I’d like to cover a thorough breakdown of what my movement literacy session involves, and how this corresponds to taking a more educational approach with your athletes. Additionally, we will cover the importance of addressing your athlete’s relationship with their body and their understanding of the training process.

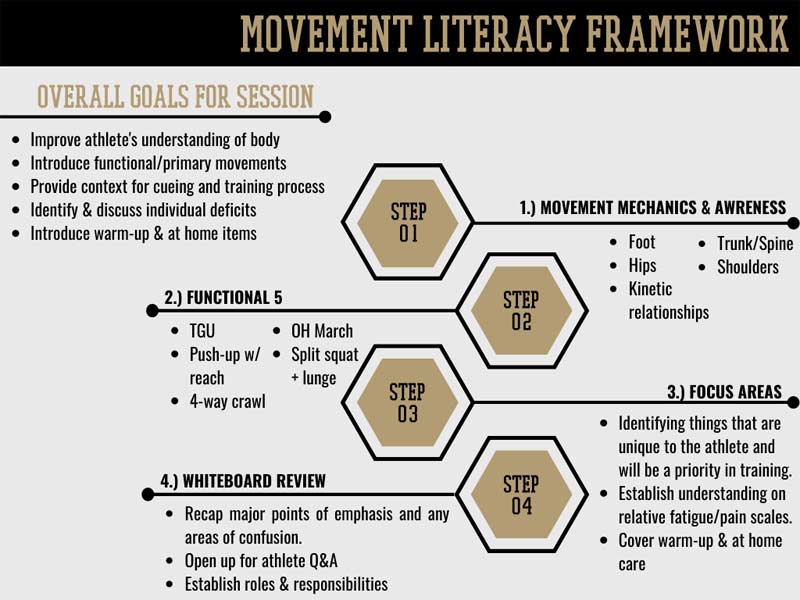

Movement Literacy Framework & Objectives

The overarching goals for a movement literacy session are simple: improve the athlete’s movement awareness and understanding of their body while providing clear insight as to what they can expect throughout the training process. Where the first session is dedicated to intake and assessment, my second session with someone is dedicated to this movement literacy session (~50-60 minutes).

In addition to the primary goals above, there are a few other elements we want to include or emphasize in the movement literacy session. We want to view this session as setting a robust foundation for the athlete to build on, and with this we want to cover all of our “big rock” items up front.

My approach includes introducing primary movements and functional patterns, providing context for frequent cues and training components, identifying individual deficits, and introducing warm-up and at-home protocols. Where I have my list of priorities from the coaching side, there is also a priority from the athlete’s perspective as well, so I make an effort to provide an environment that is welcoming to questions, input, and in some cases even collaboration.

I was told once by a military dog handler that their mantra when first starting to work with the service dogs is “Clear is kind, and kind is clear.” It just so happens this phrase fits beautifully for humans as well. I have since adopted this mantra for the sake of movement literacy concepts—being clear with your athletes is a simple way of also demonstrating kindness, as it shows you’re able to be empathetic to others, particularly those in a new environment taking on a new learning endeavor.

I was told once by a military dog handler that their mantra when first starting to work with the service dogs is *Clear is kind, and kind is clear.* It just so happens this phrase fits beautifully for humans as well, says @danmode_vhp. Share on X

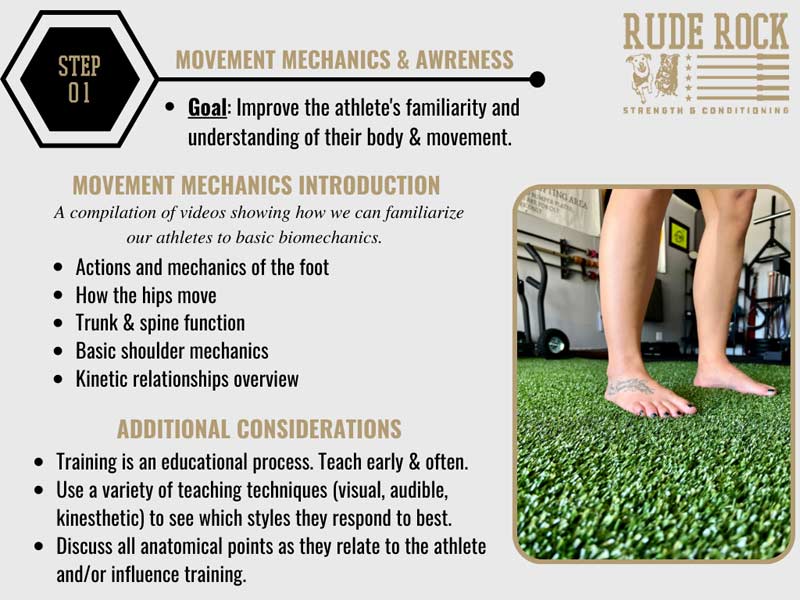

Step 1: Movement Mechanics & Awareness

The first step in our movement literacy session is dedicated to introducing movement awareness and basic functional anatomical concepts. We have been quick to assume that athletes don’t care about technical aspects of training and this has been a point of contention amongst coaches for decades.

Not only do I vehemently disagree with that stance, but I have also found that by introducing these concepts early on, it prompts a sense of responsibility from the athlete to be more engaged in the training process. Sure, of course we’re going to have situations where athletes couldn’t possibly have any less interest in the details of movement and training, but what about those who do? We cannot automatically assume that our athletes are disinterested in learning because that assumption can be a damming disservice to the ones who do.

I will typically use a combination of whiteboard illustrations, visual demonstrations, and even video recordings of how they move as discussion points. This is conducted in a simple joint-by-joint approach, where I want to give them the surface level anatomy understanding and demonstrate how it is reflected in training. My standard five points here include:

- Mechanics of the foot

- How the hips move

- Trunk & spine

- Mechanics of the shoulder

- Basic kinetic relationships

Remember we aren’t trying to bludgeon them with graduate level anatomy. We are giving them a simple introduction within the context of how it relates to our training process. I’ve found this to be especially valuable for athletes coming off injury. We should also approach this time with the intention of utilizing an of array teaching styles (i.e., visual, auditory, kinesthetic) so that we can observe how the athlete responds best to instruction.

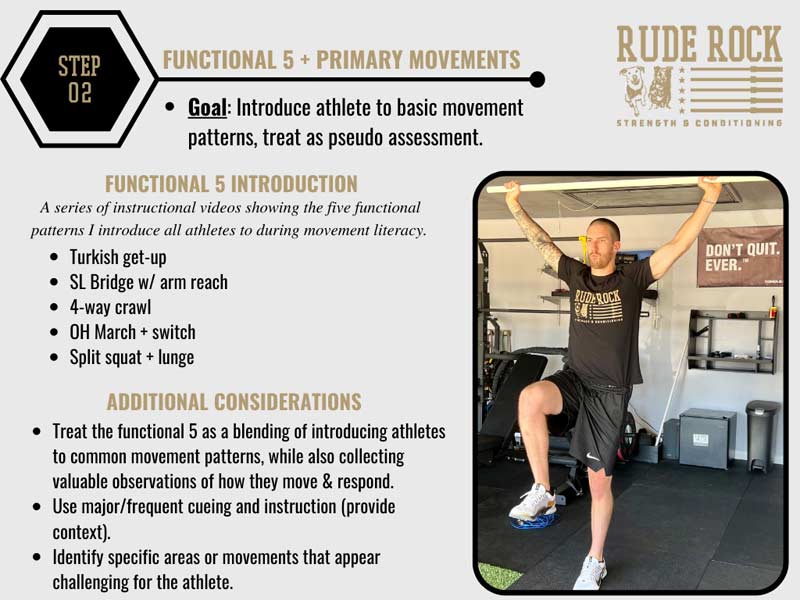

Remember we aren’t trying to bludgeon them with graduate level anatomy. We are giving them a simple introduction within the context of how it relates to our training process, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XStep 2: Functional 5 + Primary Movements

Once we have introduced the joint-by-joint and movement awareness concepts, we then want to shift to more involved elements. This begins with what I’ve termed to be my “Functional 5,” which is a simple battery that gives me multiple input points on how the parts work together. Nothing about these five movements is critical and you can populate this segment with whatever you find valuable.

Ultimately what we’re looking for here is a series of movements that give the athlete a sense of familiarity with the basics while providing coaches with an opportunity to evaluate a variety of patterns/movements. My general list for the functional 5 includes:

In addition to the functional patterns, I will also look to cover primary movements that will be performed frequently in training (i.e., squat variations, pulling, landmine variations). This is not meant to be a full install day, so really we are just touching on the primary elements involved and things for the athlete to be aware of. This provides a good opportunity to incorporate frequent cueing and context to different common positions we will work from. This not only helps to make sense of the anatomy points but also simplifies the instructions that will follow throughout training.

Step 3: Address Athlete Priorities

Where the first half of the movement literacy session is allocated for me covering my points from the coaching side, the back half is reserved for the athlete. Our primary consideration here is addressing the athlete’s individual priorities or specific deficits. Carving out time for this has been tremendously effective for me. There is a different outcome or takeaway than I normally have during a formal assessment, given that it is much more interactive by design.

Our primary consideration here is addressing the athlete’s individual priorities or specific deficits, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XMoreover, once we hit the training floor, especially in a group setting, it’s difficult for coaches to get too in-depth on individual ailments. By emphasizing this during our movement literacy session, we can alleviate this issue and clear up any ambiguity right out of the gate.

When addressing athletes about their movement limitations or injuries, it’s imperative you do so in a way that isn’t indicting or demeaning. The ultimate goal of working with injuries or impairments is treating the athlete just like any other athlete. From the way you interact and communicate to the type of exercise and training parameters, we want to keep our injured crowd as close to the norm as possible. The psychological cascade of injury is complex and can often run deep, but the last things injured or limited athletes want are reminders of it.

Beyond that, we want to assert confidence in our ability to help while providing clarity and expectations for the plan moving forward. I think it’s refreshing for the athlete to feel like they are being treated like a human. This was especially the case for me working in the tactical realm, where the inherent expectation was for training to be a carbon copy of boot camp.

Irrespective of their background, there should always be an understood presence of parity between coach and athlete. This is especially the case with injured athletes; considering how much of the medical world can be cold and dismissive, I think we are in an opportune position to provide a sense of empathy and genuine care. Remember: clear is kind, and kind is clear.

Irrespective of their background, there should always be an understood presence of parity between coach and athlete, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XStep 4: Whiteboard Review

This is effectively just a recap and summary period where we want to reiterate primary points of emphasis and goals moving forward. Somewhat of an extension from the point above, I will always be sure to allocate time for Q&A, although the goal is to have thorough dialogue throughout so there isn’t a demand for the awkward “ask me everything right now” prompting.

Nevertheless, we want to drive home two or three major points. Nobody will recall the whole session, but if we can just get even two things of value across, our time was worth it. Close the session out by reinforcing that they are an active part of this process. Not only is their input valuable, but it’s encouraged.

Training Relationships

I’ll leave you with a few points on training relationships, as they are intimately connected to the movement literacy session. Recognizing the poor relationship athletes have with training has been one of the most alarming things I’ve learned over the years. By poor relationship, I don’t mean not understanding how to put a routine together or picking bad exercises. What I mean by poor relationship is quite literally a lack of understanding the empirical purpose of training: moving better, performing better, and feeling better.

There are a ton of athletes and individuals out there who see training as an obligatory chore (at best) and as punishment (at worst). My goal in these cases is to shift their perspective of training from obligation to opportunity. We still want them to involve themselves in the training process, if not immerse themselves. At the end of the day, a lack of care or fulfillment for what we do will inevitably compromise results, even if the endeavor of training is well intended (i.e., wanting to get better for sport, improve general health). We don’t need everyone to love training, but we should do our part to at least encourage most to enjoy it.

Don’t lose sight of the underlying responsibility of being a teacher when you’re in a coaching position, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XAnd overall, make it a priority to help guide them to a better understanding and ultimately better habits and practices as they apply to training. There is of course a time and place to push the needle, but in most cases, these sessions should not represent the majority of training. Don’t allow your athletes to correlate the effectiveness of their workouts based on their sweat rate or level of exhaustion. When the training is less demanding, explain to them what the goal of the session is, because what may be seen as pointless or a waste of time to them can be a transcendent learning point. Don’t lose sight of the underlying responsibility of being a teacher when you’re in a coaching position.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF