Many coaches have achieved remarkable results with percentage-based workouts and see no reason to change. That’s fine—stay the course. I want to make the case that a repetition-based system may be a more effective and practical approach to designing workouts, and it doesn’t require a calculator or Excel spreadsheet.

To make my case, let’s take a deep dive into the pros and cons of percentage systems and then see what repetition systems offer.

(Lead photo by Viviana Podhaiski, LiftingLife.com)

Behind the Numbers

I was introduced to percentage systems a half-century ago by my coach, Jim Schmitz, a three-time Olympic Games coach. At the time, the popular term to describe these types of workouts was “intensity cycling.” I later discovered extensive articles about percentage systems through Russian articles translated by Dr. Michael Yessis and weightlifting sports scientist Bud Charniga.

Among the most referenced articles about percentage systems by U.S. sports scientists were those written by Alexander S. Medvedyev, whose periodization model is often cited in NSCA publications. However, I found the works of Arkady N. Vorobyev and Robert A. Roman to be among the most readable and practical.

One book I highly recommend for those new to the sport of weightlifting is Bob Takano’s Weightlifting Programming: A Winning Coach’s Guide. Takano “walked the talk” as an accomplished weightlifting coach, and his book is a step-by-step book about the Russian percentage system.

From here, consider investing in a copy of Supertraining by Professor Yuri Verkhoshansky and Dr. Mel Siff. Supertraining is a sports science textbook that provides an overall perspective of the Russian training system. It’s not an easy read, but it’s undoubtedly a classic resource that should be a part of every serious strength coach’s library.

The Intensity Factor

In percentage systems, “intensity” refers to the weight that can be lifted for one repetition (1RM). If you can bench press 100 pounds for one repetition, 100% intensity would equal 100 pounds. It follows that 95 pounds equals 95% intensity, 90 pounds equals 90%, and so on.

Bench pressing 80 pounds for 10 reps may seem harder than bench pressing 85 pounds once, but 85 pounds represents a higher intensity level from a program-design perspective. Share on XConfusion arises when muscle magazines refer to the intensity of training as the difficulty of an exercise, often accompanied by a photo of a massively muscled bodybuilder straining on a set of leg extensions or barbell curls. Yes, bench pressing 80 pounds for 10 reps may seem harder than bench pressing 85 pounds once, but 85 pounds represents a higher intensity level from a program-design perspective.

In the Russian system, the intensity level of an exercise influences other loading parameters, including reps, sets, and total volume. Let’s take a closer look at each.

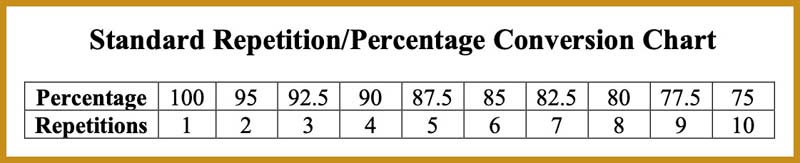

Reps. Intensity percentages are associated with the number of repetitions performed. One standard conversion equals one repetition with 2.5%, working down from 100%.

Most percentage charts skip one rep, such that two reps equal 95% rather than 97.5%. Thus, if you can lift 100 pounds for one rep, you should be able to lift 92.5 pounds for three reps and 75 pounds for 10 reps. Image 3 presents a breakdown of this formula.

Sets. The intensity level influences how many sets an athlete should perform. An inverse relationship exists between intensity and sets, such that fewer sets can be performed at higher intensities. Thus, if the intensity of an activity is 95%, 2–3 sets might be prescribed; if the intensity is 90, the number of sets might be 4–5. And so on.

Volume. Training volume is the total amount of work performed, which in weight training is the total number of reps performed. Again, total reps. This means 3 sets x 10 reps (30 reps) represents a greater training volume than 5 sets x 5 reps (25 reps).

Generally, the more advanced an athlete is, the more sets they can perform at a higher percentage. During a single month, here is how the percentage distribution might look for a power clean for a low-level and high-level athlete:

-

Low-Level Athlete

70%–75% x 20 sets

80%–85% x 10 sets

90%–95% x 5 sets

100% x 2 sets

High-Level Athlete

70%–75% x 15 sets

80%–85% x 12 sets

90%–95% x 9 sets

100% x 5 sets

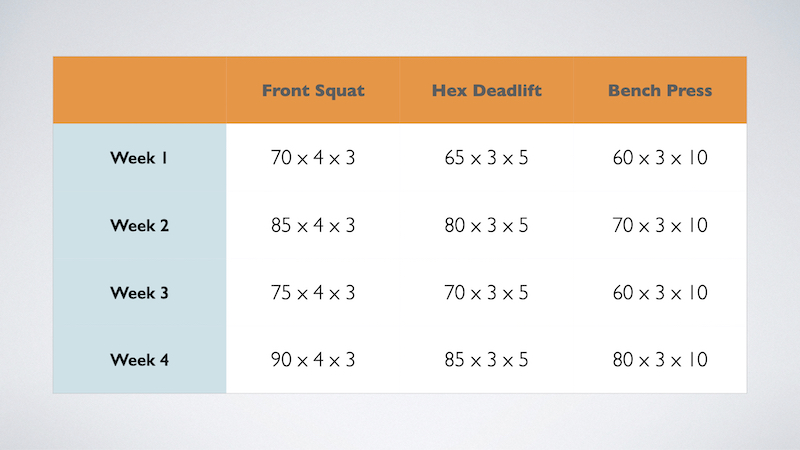

Here is an example of a four-week percentage training program using the front squat, hex bar deadlift, and incline bench press. It shows the heaviest working sets for each week:

For a weightlifter, here is how a single training session might be designed, including warm-up sets:

-

Day 1

Snatch: 70 x 2 x 3, 75 x 3, 80 x 3, 85 x 3 x 3

Clean and jerk: 70 x 2 x 3, 75 x 3, 80 x 3, 85 x 3 x 2

Back squat: 50 x 5, 70 x 5, 80 x 3, 85 x 2 x 4

To save time, particularly when working with large numbers of athletes, software programs such as Excel can automatically convert percentages into specific weights. There are also many commercial products available that will do these conversions. However, some strength coaches only give their athletes the percentages and let them do the conversions on their smartphones (except at Ivy League schools where the athletes can convert these percentages in their heads!).

The major problem with a percentage system is that it’s impossible to predict with precision what maximal weights can be lifted in each training session. Share on XThe major problem with a percentage system is that it’s impossible to predict with precision what maximal weights can be lifted in each training session. One solution is using intensity brackets rather than a single percentage prescription. Let’s explore.

The Intensity Bracket Solution

An article I found in a weightlifting textbook translated by Charniga was written by Russian weightlifting coach M.S. Okunyev. It introduced me to the concept of training brackets.

Instead of a single intensity prescription for the working sets, Okunyev used an intensity bracket that provides a range of weights. Rather than a workout prescription of 80% x 3 x 5, you could have an intensity range of 80%–85% x 3 x 5. A workout for the back squat might proceed as follows:

-

Back squat: 50% x 5, 65% x 5, 75% x 5, 80%–85% x 3 x 5

Let’s dig deeper. For the three working sets, here are a few permutations:

-

80 x 5, 5, 5

80 x 5, 80 x 5, 82.5 x 5

80 x 5, 82.5 x 5, 82.5 x 5

80 x 5, 82.5 x 5, 85 x 5

80 x 5, 85 x 5, 85 x 5

82.5 x 5, 85 x 5, 85 x 85

85 x 5, 5, 5

The system also offers flexibility because you can reduce the weight on a subsequent set if a repetition goal is not met. For example:

-

80 x 5, 85 x 3, 80 x 5

80 x 5, 82.5 x 4, 80 x 5

85 x 3, 80 x 5, 82.5 x 5

As you can see, the intensity of subsequent sets is determined by how many successful reps are completed during the previous set. Having a bad day? Stay with the lightest weight. Feeling strong? Go heavy…and then some!

Using percentages is considered a scientific way to design workouts and the optimal way to train weightlifters, but they have many drawbacks.

Percentages Predicaments

Percentage systems look great on paper and make a strength coach seem super scientific, but there may be better options. Here are seven factors that affect the effectiveness of percentage workouts:

Percentage systems look great on paper and make a strength coach seem super scientific, but there may be better options. Share on X- Muscle fiber makeup. Muscle fibers are classified according to the muscle fiber makeup, using labels such as type I (slow twitch) and type II (fast twitch) that assess a muscle’s strength and endurance. However, there is an inverse relationship between strength and endurance—the stronger the muscle, the less its endurance. This relationship presents a problem with percentage conversion charts. Let’s look at one extreme example.

-

The quadriceps are primarily slow twitch, and the hamstrings are primarily fast twitch. Using 90% of a 1RM, an athlete may be able to perform five reps in a leg curl but 20 reps in a leg press. Using a conventional percentage conversion chart, the weights recommended for a leg press might be too heavy for a leg curl.

- Gender. Many strength coaches have found that female athletes can perform more reps with a given percentage than men. Whereas a male might be able to perform four reps in a bench press with 90% of their 1RM, a female might do twice that many. Thus, the conversion charts that worked for male athletes may represent weights that are too light.

- Training age. As athletes increase their strength, they become more neurologically efficient, such that they can perform fewer reps at a specific percentage.

- Training specificity. Focusing on muscular endurance protocols, whether in the weight room or as a result of their sports training, can alter percentage conversions. For example, strength coach Charles R. Poliquin found that some elite rowers can do 12 reps at 97% of the maximum, while the average trainee will do 1–2 reps. Thus, percentage charts are not absolute for a single individual.

-

Poliquin also found this effect with the Canadian national synchronized swim team. These athletes move their limbs continuously for long periods with high-velocity movements to remain high on the water. Poliquin had athletes who could bench press 135 pounds for 20 reps but could barely manage a single with 145.

- Daily variations. We have good days, and we have bad days. On good days, a single percentage prescription can be too light, and on bad days, too heavy.

- Training schedule. When you lift can often affect how much you can lift. If you’re accustomed to lifting in the morning, you may do significantly more or fewer reps with the same weights in the evening. For this reason, athletes in many sports adjust their training to the time zone in which they will compete. If an athlete usually trains in the morning and an upcoming competition is in the evening, they should try to practice in the evening as the competition approaches.

- Exercise selection. Percentage charts are only general guidelines that cannot apply to all exercises. For example, performing high reps in a clean and jerk requires significantly reducing the percentage. Likewise, performing higher reps in the dumbbell biceps curl is easier than in the back squat.

Where do we go from here? Rather than intensity percentages, consider allowing the repetitions to determine the load.

Rather than intensity percentages, consider allowing the repetitions to determine the load. Share on XLet the Reps Determine the Load

Long before the days of personal training, gyms were a mix of powerlifters, weightlifters, bodybuilders, and those just seeking to add some muscle and lose some fat. In 1972, I joined one of these gyms, Bob Perata’s gym, in Fremont, California. Bob’s was best known as the home gym of Ed Corney, a Mr. America who appeared in the movie poster for Pumping Iron.

One of the members of Bob’s was George Perry, a personable, life-long lifter who introduced me to a descending reps workout system. He believed this method was ideal for basic weight training exercises, such as bench presses, squats, and (of course) biceps curls.

I made good progress on the workout, and after six months, at the age of 16, I could deadlift 445 pounds and do three reps in dips with 115 pounds. I also competed in the Teenage Mr. Oakland Bodybuilding Championships. (I didn’t win, but my posing routine brought down the house—as they say, “The older I get, the better I was!”)

The best way to explain how descending reps work is with a practical example. Let’s start with one you might call the 8/6/4 Training System.

In a nutshell, the basic format of this system is to perform eight reps for your first set, six reps for your second, and four reps for your third. How easy or hard this first set is determines how much weight you should lift on your second set, and the difficulty of that set determines how much you should lift on your third.

Here is a sample three-step progression for 8/6/4:

Set 1: Goal, 8 reps. This warm-up set prepares you for heavier weights and quickly assesses your current state of physical preparedness. Let’s say you can bench press 100 pounds for one rep. Take 50%, which converts to 50 pounds, and perform eight reps. It’s only 50% of your max, so you should have no problem completing all eight reps—if it’s a struggle, it would probably be best to stop and move on to something else. (Pro wrestler Ken Patera, the first American to clean and jerk 500 pounds, was known to move from exercise to exercise until he found one in which he could achieve a personal record.)

Set 2: Goal, 6 reps. For your second set, choose a weight that is 85% of your one-repetition maximum, so 85 pounds. This is where the fun begins. If you get all six reps, you could try 95 pounds for your final set of four. If it’s particularly heavy, stay with 85 pounds or, at most, 90 pounds.

Set 3: Goal, 4 reps. The rep goal on this set is four, but perform as many as possible. If you get all four reps or more, increase the weight on your next workout. Here is an example of a progression for someone who can bench press 100 pounds:

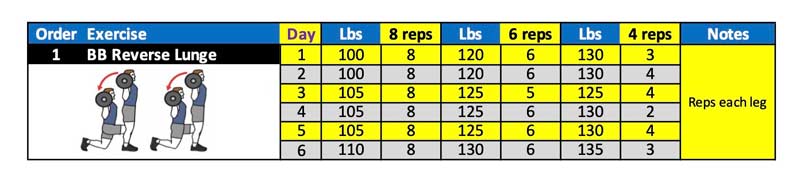

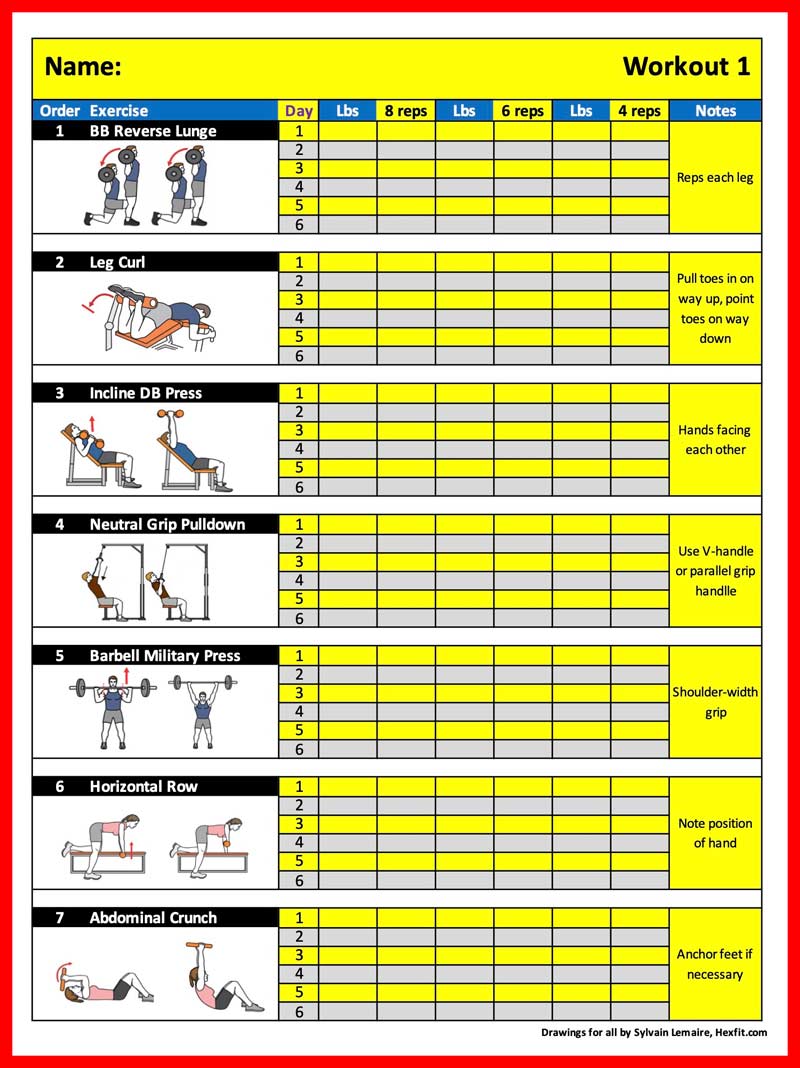

Image 6 shows what a workout card could look like for a single exercise.

Getting back to my buddy George, one of the benefits of this training system is that you are continually increasing the weight, giving your mind the illusion that you are getting stronger throughout the workout. Yes, you could start with low reps and increase with subsequent sets (so, 4/6/8), but it would have a different effect mentally that the higher reps are more challenging. This is particularly true with beginners; this may be a better approach for advanced athletes, as there is less fatigue from the lower reps.

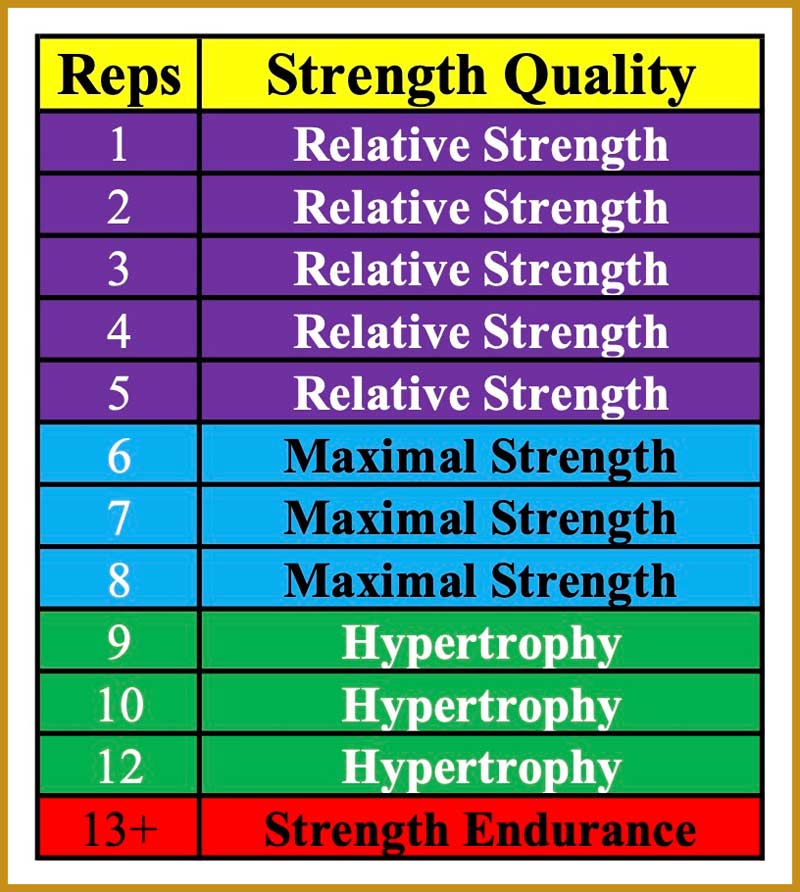

From here, you can branch off to several other variations, such as 12/10/8 for hypertrophy or 6/4/2 for more relative strength. What’s the best repetition bracket? Consider that high reps will work more hypertrophy and muscular endurance, and lower reps will have more maximal and relative strength. Image 7 shows the strength quality associated with specific repetitions, based on a 1990 research paper by Poliquin.

If you think about it, velocity-based training (VBT) uses a repetition-based system. You are prescribed a specific number of repetitions, and the feedback system will tell you if the weight is too heavy or too light based on how quickly the athlete lifts the barbell. From this perspective, VBT involves allowing the reps and movement speed to determine the load.

To avoid training plateaus, it’s best to change training protocols every few weeks. After determining the strength quality to emphasize, it’s better to stick with one repetition bracket for a few weeks and then focus on another, as follows:

-

Weeks 1–2: 8/6/4

Weeks 3–4: 10/8/6

Weeks 5–6: 8/6/4

Weeks 7–8: 6/4/2

Weeks 9–10: 8/6/4

The criticism of this workout is that there is only one hard set per exercise, but for beginners, it’s enough. Advanced athletes can add more sets, such as 12/10/9/8 or 6/4/3/2. However, so the body knows what strength quality it’s supposed to adapt to, you should generally keep the repetition spread to four reps (12–8, 11–7, 10–6, and so on).

Also, consider that many high school weight training programs are overwhelmed. I’ve known weight training programs with 70+ kids and one instructor, so a simple program such as 8/6/4 can be a good start. Here is an example of a workout card using a repetition system that athletes can fill in.

When I was the editor of Bigger Faster Stronger magazine, I wrote articles about a set/rep workout card they developed for their workouts. Thousands of athletes and PE students used these cards. BFS also had a software system, but many coaches I interviewed said they liked the workout cards because they get the athlete actively involved in the training process. They also told me that their students enjoyed writing down their personal records.

For practical examples of using repetition-based programs with your athletes, I refer you to the early works of Australian strength coach Ian King and Canadian strength coach Charles R. Poliquin. Two classic books to get you started are How to Write Strength Training Programs: A Practical Guide, by King and The Poliquin Principles, by Poliquin (As a matter of full disclosure, I was the editor of The Poliquin Principles).

Those teaching weight training at the high school level are often overwhelmed by large numbers of students in each session. Repetition workouts might offer a better training experience. Share on X

From a practical perspective, consider that teachers in charge of weight training classes at the high school level often have little background in designing workouts—and you probably won’t catch many of them reading Russian research papers on periodization methods in the break room. They are also often overwhelmed with large numbers of students in each session. Using repetition workouts might offer a better training experience for their students.

Technology has much to offer the strength coaching profession, and percentage workout systems are here to stay, particularly for weightlifters. However, sometimes it’s better to put down the smartphone and get strong the old-fashioned way by letting the reps determine the load!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Charniga, Bud. Charniga offers many translated Russian weightlifting textbooks and yearbooks on the following website: https://www.dynamicfitnessequipment.com/category-s/1819.htm

Takano, Bob. Weightlifting Programming: A Winning Coach’s Guide. Catalyst Athletics, Inc., 2012.

Siff, Mel and Verkhoshansky, Yuri. Supertraining, 1999, 4th edition, Supertraining International, Denver USA 1999. (1st edition, 1993)

King, Ian. How to Write Strength Training Programs: A Practical Guide, King Sports International, 1998.

Poliquin, Charles. The Poliquin Principles, Dayton Writers Group, 1997.