Being a coach, athlete, and human being means being creative. Creativity is a given in the arts: music, film, dance, painting. Coaching has several “artistic” aspects, but the creative application of training means is rarely emphasized.

Perhaps part of this is because so much of what we would call athletic performance is typically “prescriptive” in nature. Strength coaches often tell you about what protocol they run, whether Triphasic, Tier, 1×20, or 5/3/1. Even in speed training, there is often a popular sequence, perhaps with a mechanical sprint device that is prescribed to athletes, and in jump training, a particular depth-jumping protocol.

In some ways, we could say this is the nature of sports performance relative to sport and skill coaching: treating physical qualities—and rudimentary skills—as basic and trainable through a prescription of exercise. No creativity is required, just the general stamp of approval of the coaching community or whatever relevant research or data collection might be available.

To coach is also to create. Complex coaching is to take various colors and brushes and create something new, something that serves the needs of the athletes in front of you, says @JustFlySports. Click To TweetAlthough these prescriptions clearly deliver results, to coach is also to create. Complex coaching is to take a variety of colors and brushes and create something new, something that serves the needs of the athletes in front of you with the equipment you have available (or lack thereof). One of the apexes of creativity in athletic performance, especially when there are a multitude of training means available, is found in complex training. Complex training is the mixture and combination of training means, relying on the synergy of the whole being greater than the sum of the parts.

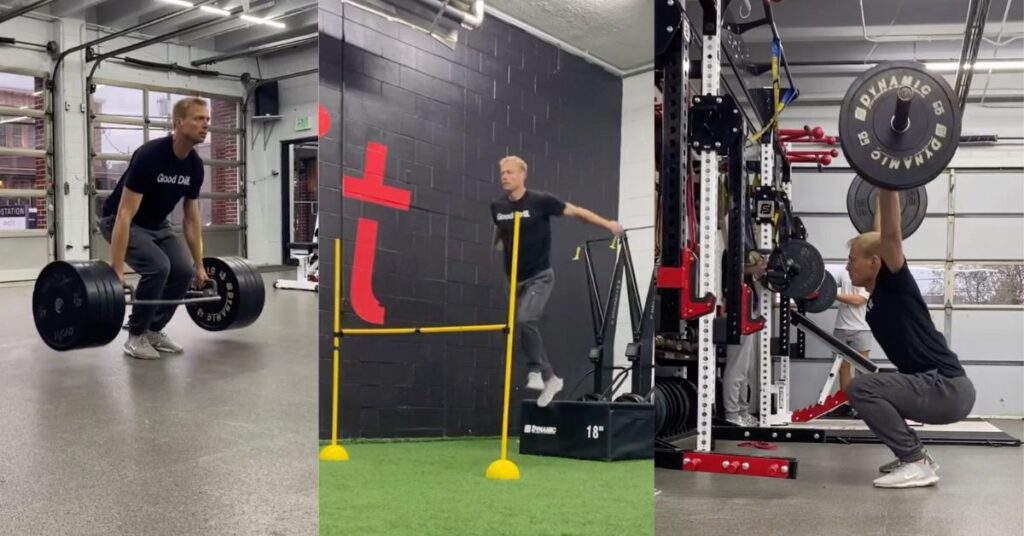

Video 1. Sample French Contrast sequence for jump power development.

Originally, complex training was defined as alternating heavy strength training with plyometrics. The research threads tend to focus on the specifics of potentiation, how much to lift, and how long to rest. It runs far deeper than “lift heavy weights, rest 10 minutes, and do some plyos.” In reality, complex training is a wide net that can encapsulate anything from wave loading and energy system alternations to purposeful circuits of exercises designed for either a potentiation or coordination challenge (or both).

The 1980s and the Wellspring of Complex Training Genius

Ironically (or perhaps not so much), the greatest displays of creativity in the realm of complex training came from an era out of the past rather than the present. Music critics claim the 1960s to the 1980s were the richest decades musically, and the 2010s were the most monotonous. If you want to be a good musician, it’s a given to find inspiration from the greats of the past—and a tremendous influence on modern music has been from previous decades.

The material of the past is fundamentally invaluable for a complete understanding of physical training. There is so much training from the 1980s that coaches regularly refer to, such as the work of Charlie Francis. Track and field jumps training, as well as plyometric training, was taking off in this period (literally), and some of the best strength research came from the 1980s as well. This is not to mention the highly funded Soviet research done with actual athletic populations conducted more than 50 years ago.

Regarding complex training, there are two coaches of the past whose work demands our study. Jean Pierre Egger coached from the 1980s (Werner Gunthor) into the 2010s (Valerie Adams). Giles Cometti was not only a track coach but also a professor and performance center director whose work spanned from track coaching in the 1970s and research beginning in the 1980s into books published through to 2010. The more you study them, the more you realize that both were not only ahead of their time, but much of modern training still hasn’t caught up. Between the two, there is also a substantial amount of common material and concepts and a synergy of the developing ideas of the time.

Jean Pierre Egger was a world-class thrower himself and the brains behind the Werner Gunthor training material. The Gunthor training series is one of the most popular by far, and 40 years after its inception, coaches still love watching a 300-pound man perform various feats of complex and explosive training. Egger used a variety of methods, from pre-fatigue to agonist-antagonist pairing to pressurized eccentric overload machines and, of course, creative complex training methods.

As things progressed through the 1990s into the 2000s, the focus of complex training grew simpler rather than more complex, says @JustFlySports. Click To TweetIn the time since the 1980s, complex training didn’t seem to accelerate as much as take time to see more rudimentary versions validated by the research. As things progressed through the 1990s into the 2000s, the focus of complex training grew simpler rather than more complex. My graduate school’s focus on complex training in 2007 mentioned nothing of Cometti or Egger. Rather, the focus was simply on the premise of basic potentiation, if a heavy lift could make your vertical jump higher 5–10 minutes afterward.

Much of the training throughout that time (2000–2010) resonated with the powerlifts and perhaps a related regression into more simplistic models. Egger, on the other hand, utilized specific complexes based on the phase of preparation and the plane of muscular motion. In more strength-oriented phases, pre-fatigue, agonist-antagonist work (shown here: 6:28–6:35), and specific eccentric overloading were staples (shown here: 1:58–2:15).

In power phases, strength work was paired with plyometrics in the same plane of motion and joint action. Advanced variations combined plyometric variations in essentially an “obstacle course” format, keeping things highly task-oriented (activating the salience network of the brain) while infusing natural variety. These movements were also high intensity in nature (see more Gunthor here), which differs from much of the watered-down, multi-planar plyometric work seen today, which seems more about the sequence than the stimulus and intensity.

Where contrast training was a centerpiece of the Gunthor training series, a French coach and researcher was simultaneously laying the foundations for modern complex training adaptation. Giles Cometti was the inspiration behind “French Contrast Training” (as per Cal Dietz), the training complexes of Christian Thibaudeau, and methods used by many other coaches.

In studying and translating the works of Cometti, as well as speaking with other influential coaches, I’ve found that his work is inspirational to modern coaches and is foundational and robust in its own right. It may be the language barrier that kept the work of Cometti from really striking the coaching means of the West, but it stands up as both years ahead of its time and highly creative and integrative of multiple athletic performance qualities.

Cometti was listing the pros and cons of the major muscle contractions (concentric, eccentric, isometric, plyometric, electrostimulation) 40 years ago, discussing how to combine these training methods in a way that maximized the positive while diminishing the drawbacks. These pros and cons are rarely discussed today. He also heavily used electromyography and had a deep understanding of the underlying neurological wiring and activation systems of motor units. He understood the nature of muscle twitch, partial and full “tetanic” contraction, and the unique impacts of long-duration isometrics from a motor unit synchronizing perspective. You would see all this at play in his complex training design.

Beyond the basic physiology, a major highlight in Cometti’s work was his emphasis on integrating a relevant sport movement into a complex circuit and being mindful of how various plyometric or special strength pairings could ultimately fit with specific sport skills, such as a volleyball block, soccer kick, or flying header. Few in the training world have so eloquently and creatively combined these specific means as Cometti did back in the 1980s and 1990s or had the extensive library of methods, along with the physiological backing of understanding.

Have We Built on Training of the 1980s?

Watching the Gunthor training series in the 1980s, you would think that modern training would be regularly infused with purposeful and specific creativity, as well as with the potential for task-specific sport efforts. More often than not, however, we see diluted versions rather than work that has truly built on it or integrated it. Part of this may be cultural, in lockstep with what is seen in music and film, but I believe there are also other reasons.

Today, there is an increased separation unfolding in the sports training process. There is the sport coach, the player development coach, the strength coach, the speed coach, the nutrition coach, the mental coach, and the high-performance coordinator. Egger was the coach for Gunthor. Cometti had a prominent sports science position and his own lab/gym. This isn’t to say there isn’t a high level of value in each of these individual positions, but it’s more speaking to the fact that the roles within sport itself have been increasingly specialized, and the container of sports performance doesn’t outright reward creative integration in exercise selection.

The roles within sport itself have been increasingly specialized, and the container of sports performance doesn’t outright reward creative integration in exercise selection, says @JustFlySports. Click To TweetWithin the silos, much of creativity now focuses more on singular strength training iterations or perhaps plyometric methods in their own capacity. This brings us dozens of iterations of squat, bench, and deadlift variations, unilateral lifts, “functional” training adaptations, and various re-hashes of plyometric movements. Novelty now works more for the individual container than for how movement can be integrated back into sport. The exact emphasis tends to go in waves, with varying strength methods waxing and waning in popularity over the years and decades.

Keeping with the nature of the job, sport coaches are relied on for the motor learning, tactical, and technical processes, which thrive on more “messiness,” non-linearity, and complexity (and those coaches are rarely educated in the subject). Strength coaches, meanwhile, are primarily in charge of “prescriptive tissue enhancement and stress management,” to put it a particular way. Keeping tissues healthy is an incredibly important job, but keeping one’s job tends not to require a creative quest to maximize specific KPIs or athlete movement patterning.

New technology and data collection also give coaches other ways to explore the realm of basic strength training, such as with bar velocity or readiness indicators. Some coaches certainly explore the breadth of complex training in a quest to maximize the athlete’s performance and engagement, but the way success in physical preparation is framed doesn’t facilitate maximizing KPIs as a requirement.

Complex Training in the Modern Era

So, how has complex training moved forward, and who has picked up the baton? What can we learn from the current iterations of complex work, combining strength, plyometrics, and speed for an optimal result? Where is complex training most applicable across the breadth of specific skill training and in general physical preparation?

For this article, I am listing modern iterations of complex training with five coaches who highlight creativity and practicality in building on the giants of the past. Each example points to global principles and strategies that can be taken into a coach’s own unique situation and an understanding of how the nature of sport (individual versus team) has influenced how complex methods have moved forward over time. These break down between the weight room (general preparation) and more skill-specific means (track and pitching/fast-bowling).

Weight Room-Oriented

- Cal Dietz: French Contrast + Multi-Stage Complexes

- Christian Thibaudeau: “Insider Complexes”

Speed and Sport Specialty-Oriented

- Chris Korfist and Dan Fichter: DB Hammer-Inspired Speed Complexes

- Steffan Jones: Fast-Bowling Specific Complexes

Weight Room-Oriented Complexes

When it comes to the gym, whether it is a strength or speed adaptation, strength coaches throughout history have seen the value of wave loading. Whether it is a Poliquin style “6,1,6,1,6,1” rep scheme, going 3,1,3,1,3,1 on Olympic lifts, or even a basic drop-set of 15–20 reps after a 3×3 heavy set, the value of a wave in the gym is written into general training philosophy.

In “general” preparation, there are more options as to the exact purpose of the wave or complex, but largely, locomotion, sprinting, and jumping are the most transferable KPIs coaches are looking to build. I’ll share here some ideas from Cal Dietz and Christian Thibaudeau, both of whom are inspired by Cometti.

1. Cal Dietz

Many coaches are familiar with Cal Dietz’s “French Contrast” ideation, inspired by the works of Cometti. Cal’s classic version goes as follows:

The above is done for 1–5 sets, with three being most common, and is highly effective. Vertical jump increases of 10% in a short time using this method, and similar increases in acceleration and throwing ability are not uncommon. I’ve written articles about this format in the past, and adapting various exercises to this sequence invites coaches to leverage their own physiological and biomechanical expertise creatively. Not only is this type of contrast effective after several sessions to substantially improve explosive athletic qualities, but it can also provide significant potentiation within the session itself. For example, it is easy to accomplish vertical jump increases of 3+ inches (8 centimeters) from the first set of contrast to the last (after 3–4 sets).

In the time since the original French Contrast, I had a wonderful podcast with Cal where he described moving into contrast work with even more stages—which he called “performance cycling”—with the distinctive purpose of using strength work as a technical amplifier. One low-hanging fruit for creative integration in modern complex work is the connection between exercise selection and movement quality. As Cal stated in the podcast:

“I would start my first set with my quad-dominant athletes at the rear posterior chain exercise and then cycle through everything, which is actually better, Joel, for my weight room functioning.”

This series may look something like the following:

The purpose of more movements in a set is related to washing out the discoordination caused by doing multiple sets of a movement, like a back squat, consecutively while simultaneously using other movements to help bring up weak points (such as a glute-ham raise for a posterior-chain-need individual). The ultimate goal is improved coordination, as evident in the dynamic movements in the series (in the case of the above, the sprint and bound activities). Where the French Contrast is more pure power, this adaptation is more technical, emphasizing the functional movement patterning of the athlete.

2. Christian Thibaudeau: Strength and Power Complexes

I’m not sure there is a modern coach with more complexes in his training toolkit than Christian Thibaudeau. His book Theory and Application of Modern Strength and Power Methods is an absolute classic. Christian speaks of complexes from ascending (light to heavy) to descending (heavy to light), pre-fatigue, post-fatigue, and more. If you are looking for complexes to maximize that strength and power portion found exclusively in the weight room, then understanding Christian’s work is required.

One of the more unique complexes Christian prescribes is “insider contrast,” which he notes is inspired by Cometti’s work. There are many iterations of this, but an example is as follows, all done on short rest in each superset:

This type of “insider” contrast trains many windows of strength on the same training day and in the same set. In a way, it can uncomplicate the process of working out longitudinal periodization as multiple qualities are trained on the day in an interesting and engaging way, and the exact method can be cycled over time.

Speed- and Sport Skill-Oriented Complexes

I believe that in sports where speed is not only desirable but is the sport itself (track) or a massive and direct contributor to success (pitching and fast-bowling), complex training is perhaps the most applicable. There is a reason that Jean-Pierre Egger was a track coach. When it comes to whatever is needed to work out the last few percentage points of performance, it’s nearly a given to look to complex training means.

When it comes to whatever is needed to work out the last few percentage points of performance, it’s nearly a given to look to complex training means, says @JustFlySports. Click To Tweet1. Chris Korfist and Dan Fichter: Sprint Complexes

In one of the greatest training DVDs (you could call it “old school” at this point), Wannagetfast V.1, Dan and Chris go through many of their sprint-specific complexes, many of which are inspired by a coach with the pen name “DB Hammer.” These combine flying sprints with plyometrics, with more “metabolic” calf and lower leg work. One of their prime complexes, which sticks with me in many of my own programming iterations, is as follows:

In the spirit of the DB Hammer literature, this type of complex would be programmed for rounds until a “drop-off” in the time or quality of key performance markers.

Performing a speed complex in this way trains the body in an incredibly robust manner, with each explosive movement having the capacity to improve the flying 10 and a specific strength adaptation of the body positive to sprinting.

2. Steffan Jones: “Second-Generation” Contrast and Fast-Bowling

The specificity and specific power development of complex training have been used brilliantly toward the outcome of fast-bowling speed by Coach Steffan Jones. Whereas Christian Thibaudeau is a master of creativity in strength complexes, I don’t know of any sports skill performance coach with more extensive complex training in their toolkit than Jones. Jones has included advanced complexes in his fast-bowling regimes, not only through strength overload but also by manipulating the weight of the ball, integrating special developmental work, and working both heavy and light loads in the same complex. The spirit of the “second generation” is plugging deeper into the specificity of a single movement.

Here is a sample of one of Jones’s multi-weight complexes.

Video 2. Steffan Jones has taken complex training in sport skill to a new level in the modern sports world.

Within the skill of a single movement, Jones also puts together complexes that train the coordination of each “node” in the network of the overall throw. While some complexes are more raw power-oriented, there can be complexes meant for coordination and skill as well. (Similar to Cal’s performance cycling, but Cal’s cycling was more driven toward locomotion, a more “general” ability than fast-bowling.)

When athletes experience multiple “shades” of their sport skill, their bandwidth for improvement is greater. When athletes long jump a variety of distances, instead of all maximal efforts (such as in the classic “Rewzon” study), they end up jumping farther at the end of a training phase. By working contrast heavily into a singular sports skill, there is a density of opportunity for both athlete learning and specific power production. This is not dissimilar to experiencing different “shades” of barbell lifting style, as shown in Christian’s version of Cometti’s strength work. Humans are meant to experience different shades and versions of training.

Integrating Creativity in Complex Training

Although the core of training is simple, complexes are perennial “plateau” busters and chances to integrate multiple “nodes” of the training network in a creative manner. Whether a simple descending power series or a more elaborate adaptation, complex training yields a multifaceted stage for athlete improvement. It also helps satisfy an inherent human need for creativity and novelty in coaching.

Although the core of training is simple, complexes are perennial ‘plateau’ busters and chances to integrate multiple ‘nodes’ of the training network in a creative manner, says @JustFlySports. Click To TweetAs I have gone through many variations of complex training, I’ve found that the following “ingredients” in a complex can make sense for the corresponding situations:

Strength and Power Priority

- Overcoming or yielding isometrics.

- Heavy strength work.

- Unique strength machines, such as Keiser, kBox, or Supercat.

- Depth and assisted jump variations.

- Resisted and assisted sprinting.

- Medicine ball throws for distance or velocity.

Movement Quality Complexes and Elasticity

- Rhythmic and tempo-oriented movements.

- Proprioceptive challenges (i.e., hard balance discs or physio balls).

- Isometric holds to fatigue or sub-fatigue.

- Locomotive plyometrics (i.e., flexed leg bound).

- Short or long sprinting and locomotive constraints.

Sport-Specific Adaptation

- Relevant isometric positional holds.

- Specific strength drills (“SDE” in the Bondarchuk classification).

- Exploration of basic sports skills such as swinging, kicking, throwing, jumping, sprinting, and changing direction.

- Varying intensities and loads of one’s primary sport skill.

- Tracking and single-object manipulation.

The question is, does this build on what we’ve seen from the giants of the ’80s? Can we really “improve” on Led Zeppelin, Pat Benatar, or Prince? Do we push restart and time warp? Although so much has been done already, we are in a position where we can grab from a variety of methods and apply them to the athlete or group in front of us.

Does the athlete need strength, general power, and confidence? A basic French Contrast circuit can do wonders. Does the athlete desire to connect the gym to a specific skill? Cometti sequences with an actual sport skill iteration on the tail end of the circuit are a great option. Does the athlete seek better movement quality and injury resilience? More of a performance patterning using longer isometrics and proprioceptive challenges can be effective, as I believe the complexity of sport demands more out of preparation than simply: “lift more weight” or “move lighter weights faster.” Simple demands yield simple adaptations, but complex demands need more complex and thoughtful adaptation processes.

The groundwork has been laid, so there has never been a better time to work from the existing sea of knowledge and creatively weave training into your own situation, says @JustFlySports. Click To TweetThe groundwork has been laid, so there has never been a better time to work from the existing sea of knowledge and creatively weave training into your own situation. If you are interested in learning more about complex training and artistry in performance coaching, then you’ll want to check out the “Escaping the Training Simulation” seminar with Austin Jochum on June 8 in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Hello! How do I get in contact with Joel Smith regarding his online course Elastic Essentials”

Thanks

Excellent article! Thought-provoking and insightful. Thanks!