As performance coaches, we often feel a sense of doubt about how much our training in the weight room and on the field contributes to the performance of our athletes. Are we actually moving the needle in their performance? At the very least, we constantly question how we can better tie the needs of our sports into our programming. One of the ways we have found to bridge the gap between sport and the weight room has been by using partner combatives.

Partner combatives are a way to create one-on-one physical contact between athletes in a controlled and competitive way. They connect traditional training (e.g., squat, hinge, push, pull) and crucial aspects of sport by putting athletes in a position to use their strength in a specific manner—as opposed to exerting force against an inanimate object (barbell, dumbbell, the ground), partner combatives require athletes to exert force against another person.

While traditional movements help athletes increase their ability to apply force into the ground, we feel there is a more specific way to train an athlete’s ability to apply force into another person (another aspect of force application in sport). Additionally, partner combatives enable us to introduce and program contact within training at all times of the year. This can allow for a shorter and more efficient acclimatization period when those sports reintroduce contact within practices during pre-season periods.

Partner combatives enable us to introduce and program contact within training at all times of the year. Share on XCoaches of contact sports often bemoan an athlete’s or team’s inability to “be physical,” or they express that their athletes “shy away from contact.” Programming partner combatives with those teams allows each athlete to be exposed to the stimulus of “contact” all year round. A controlled stimulus used to improve that specific, physical quality is something that these athletes won’t get anywhere else.

Identifying the Problem

During our time working at the University of California, Davis, we often had conversations around the effect our training had on our athletes’ performance on the playing field. Our conversations generally revolved around questions like:

- Is there more we can get from a squat other than improving an athlete’s ability to put vertical force into the ground?

- Can we enable athletes to improve force application into the ground AND against other bodies?

While these were questions most applicable to sports like basketball, football, soccer, etc., we asked additional questions about sports that aren’t played on the ground. (e.g., How can a bench press help a water polo athlete manipulate an opponent’s body similarly to an offensive lineman in football?)

As we sat down to further study certain sports, we consistently came across situations of intense physicality: water polo players fighting for position in front of the net or basketball players constantly fighting for position boxing out and rebounding. Notice how these players are required to put force into the ground AND into other bodies—bodies that are not stationary but battling to carve out space. There are physical battles in almost every play in sport. These often have a large hand in deciding the outcome of those contests.

In identifying these situations, conventional weight room programs didn’t feel adequate to best prepare our athletes for the demands of their sports. In discussion, we asked:

- How can we help to prepare these athletes for such a big part of competition through what we do in the weight room?

- How can we introduce contact/physicality within the weight room in the most controlled way possible?

Our answer? Partner combatives.

Categorizing and Programming Partner Combatives

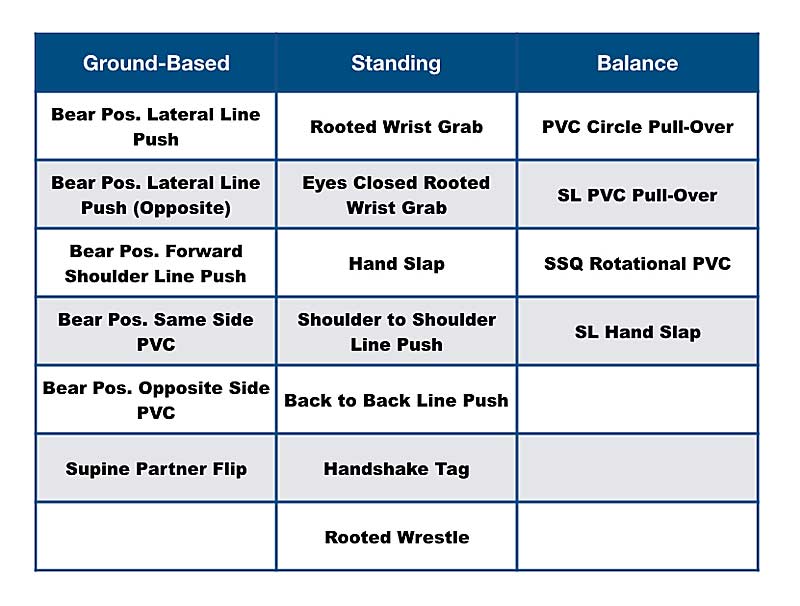

We separate partner combatives into categories. Some of the combatives are simple, some are more complex (meaning we typically don’t trust teams with the more complicated ones until they’ve proven they can handle/control themselves):

Typically, we start our teams in positions of a partner combative, but we leave out the competitive component until they get a better grasp of the movement/position. (It’s fairly subjective when that is.) For example, we may have athletes start in a standing shoulder-to shoulder line push position; however, one person is giving ground while applying resistance as their partner moves them.

Video 1. Shoulder-to-shoulder line push as one athlete gives resistance and ground to the other.

Once our athletes show they are capable of these controlled positions, we’ll start the competitive side of partner combatives. However, we can still keep it controlled by limiting their time in competition (3-5 seconds).

Video 2. Shoulder-to-shoulder line push where both athletes fight to get over the line. There’s a short timeframe and not necessarily a clear winner or loser.

As our athletes show more competency, we allow them to build out the total time of the combative or have them go until there is a winner and loser.

Video 3. Bear position lateral line push combative. We let athletes battle until there is a clear winner and loser, however long that may take.

It is important to keep in mind that not every team or athlete goes through the same progressions. Some teams/athletes we’ve trusted go right into competition on day one, or at least use different variations of full partner combatives that aren’t quite as “violent.”

Video 4. PVC SL pull-over combative, where the athlete’s goal is to unbalance their partner first (lower on the “physical”).

Programming Partner Combatives: When and Where

In the weight room, we typically superset our major movements with whatever partner combative we want to use within that day. We’ve seen combatives be a great way to set the tone for the rest of the training session and allow athletes to feel the connection between a general movement (bench press) and specific movement (rooted wrist grab).

When explaining the “why” behind our program, it shouldn’t be up to the athletes to just trust what we’re saying. They can feel how a traditional movement in the weight room can pair with and complement a sport-specific situation. Athletes enjoy competing, and programming combatives early in a session typically creates a better, higher-energy training environment. Combatives force athletes to train with high levels of intent immediately within a workout. There is nowhere to hide when you’re doing a partner combative.

Combatives force athletes to train with high levels of intent immediately within a workout. There is nowhere to hide when you’re doing a partner combative. Share on XIf a training session is outdoors—speed, conditioning, etc.—then we like to put partner combatives near the end of the warm-up. Again, similarly to the lift, we want to prioritize combatives near the beginning of the session and allow the competitive energy from the partner combatives to carry into the rest of the training session.

Choosing Appropriate Combatives

When using partner combatives, our goal is to mimic the physical nature of the sport we are programming for. For example, we use the rooted wrist grab partner combative frequently with men’s and women’s water polo teams because of the constant hand fighting/grappling that happens in the water. However, this isn’t one that we use often with basketball teams. Instead, we’re more likely to see a combative like a standing back-to-back line push. This would more closely mimic a “box out” position.

That being said, we can still implement partner combatives in a general to specific way. A basketball team may benefit and enjoy something like a rooted wrist grab in an early off-season period to build competitive energy and general strength qualities. However, as we transition through the off-season and into the preseason, these combatives can now begin to emulate the sport. This prepares athletes for what they will experience in their competitive environment. Reverse-engineer the physical nature of the sport to build the starting points for the partner combatives that best complement the training of that sport.

Reverse-engineer the physical nature of the sport to build the starting points for the partner combatives that best complement the training of that sport. Share on XAre We Actually Making a Difference?

Since implementing partner combatives, the golden question is: What are the objective measures of increased performance that we can point to for these sports? Truth is, we don’t have any. All we have are the anecdotal and subjective feedback reviews we’ve gotten from sport coaches and athletes. That feedback has been overwhelmingly positive in an attempt to tie the needs of specific sports into the weight room.

While objective measures are obviously important, we believe that performance coaches should implement and rely on subjective measures like watching the athletes compete in their competitive environment and put value in “reviews” from the players and the sport coaches.

Closing the Gap

Partner combatives have been one of the ways that we’ve been better able to bridge the gap between training in the weight room and on the court or field or in the water. Unsurprisingly, as athletes have begun to buy into this process—seeing training that they can directly relate back to their sport—they’ve more quickly and eagerly bought into the “traditional” training as well.

Give a little to get a little—even if we aren’t actually giving anything. Partner combatives might not be the best training method for every team/coach. However, they are one attempt in a continued and constant search to find the best ways to prepare our athletes for their sports.

Authors’ Note: While this article comes with our dual byline, we have taken and applied these exercises to our environments from a few sources, including Elon Sports Performance, Michael Zweifel, and Austin Jochum. Thank you to these people for educating us and continuing to push the field forward. Finally, thank you to SimpliFaster for the platform to share our ideas within our community.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Hunter Eisenhower is the Associate Director of Sports Performance at the University of California, Davis. He works with men’s basketball, baseball, and lacrosse while assisting with football. He has previously worked at Southeastern Louisiana, Minnesota State Mankato, and the University of Washington. Hunter was a collegiate basketball player at Seattle Pacific University. IG & Twitter: huntereis_sc

Hunter Eisenhower is the Associate Director of Sports Performance at the University of California, Davis. He works with men’s basketball, baseball, and lacrosse while assisting with football. He has previously worked at Southeastern Louisiana, Minnesota State Mankato, and the University of Washington. Hunter was a collegiate basketball player at Seattle Pacific University. IG & Twitter: huntereis_sc