Vas Krishnan is a sprint coach, physio, strength and conditioning professional, sports scientist and athlete. Krishnan’s drive in sports performance and rehab for track athletes comes in part through his own myriad of injury issues (both surgery and early-stage mismanagement). He takes a unique, multi-faceted, and holistic approach to coaching and therapy, which is displayed through his assistance of Andrew Murphy and his group of elite power athletes (sprints/jumps). Krishnan has held multiple positions and worked with a range of different athletes from novice to sub-elite to elite. Most notably, he has been coach/therapist for Australian Junior National medalists and a number of Opens athletes in the top 10 of the 100m and 200m.

Freelap USA: Your social media handle is @thesprinting_physio on Instagram. Can you describe some of the ways your physiotherapy background compliments your sprint coaching? How helpful is it to be the same guy who both looks after the athletes from a medical perspective and a performance perspective. Also, how mutually exclusive are the two?

Vas Krishnan: I think being a therapist compliments my coaching, and vice versa. Whilst we can implement strategies to mitigate injury risk, the reality is that at some point, most athletes are going to suffer an injury. Being the person who was present leading up to the injury and immediately after the injury allows for a deeper understanding of the cause, and therefore allows for a more appropriate rehabilitation plan and generally a better continuity of care.

Whilst we can implement strategies to mitigate injury risk, the reality is that at some point, most athletes are going to suffer an injury. Share on XIn Australia, funding does not always allow for training groups to have vast resources, so it’s advantageous to be multi-skilled—so, for example, you have many coaches who are also a massage therapist, physiotherapist, or chiropractor. Angus McEntryre, who coached Mackenzie Little to a bronze medal at the World Championships in Budapest, is a great example of this. Circling back to funding, it makes it easier logistically—and financially—for the athletes to have a coach who is a ‘one stop shop’ and can manage multiple aspects of their preparation.

Whilst being able to wear both hats cuts out a link in the chain of communication back to the coach regarding any injury issues, it also comes with an extra layer of responsibility—should I miss something in my analysis, there’s no one else to pick up on that and hold me accountable. Looking at a typical team environment, you’d have:

- A medical team who deal with the very early stages of the injury management.

- A rehabilitation physiotherapist who bridges the gap between the very early stages of rehabilitation and performance

- A performance specialist, such as a strength and conditioning coach, who completes the final stages of returning the athlete to play.

For my athletes, I cover all three bases. If I had the option to have other expertise involved, I certainly would, because I think the best results are often a product of collaboration. It’s helpful to have a fresh set of eyes on things and gain different perspectives—I was listening to John Nicolosi on his Melbourne Athletic Development Podcast and he mentioned that he doesn’t like to always treat his athletes for this reason, and you will find this with multiple other therapist/coaches. To freshen and broaden my perspective, I have a network of coaches and practitioners I reach out to, such as Andrew Murphy, Nik Hagicostas, Christopher Dale, Angus McEntryre, Nick Cross, and Trish Wisbey-Roth.

To your point about the mutual relationship between health and performance, both of those qualities are absolutely on the same spectrum and I have seen coaches do a great job in rehabbing a hamstring issue, for example. Their experience of physiology, dose potency, and how to overload structures lends itself to being able to bring an injured athlete back to full health, and I think they often do a better job than physios in the end stage of the rehab process. I think it’s more common nowadays to see coaches either from a medical background, or those who go and seek some formal education in that domain to deepen their understanding.

These days, coaches are often becoming more formally educated, with degrees, master’s degrees and more, which highlights the value of coaches having a deep understanding of the human body—it’s almost becoming a requirement! I think there’s an argument that a large part of good strength and conditioning is simply really good rehab or prehab. When Jonas Tawiah-Dodoo came to Sydney, I was at one of his workshops and he said that when an athlete is rehabbing from an injury, it highlights the things they need to do rather than doing all the things they want to do. What they need to do will always be things they need to do. Sometimes it takes an athlete being injured to reinforce what needs to be a part of the strength and conditioning programming.

This is one of the main appeals to training with me, I get a lot of athletes join me who have quite a big injury history, so they appreciate that I have experience rehabilitating other athletes and have strategies in place to mitigate against the most common injuries.

I think it’s more common nowadays to see coaches either from a medical background, or those who go and seek some formal education in that domain to deepen their understanding. Share on XFreelap USA: You assist Andrew Murphy with his group, and he likes to implement technology to guide and enhance his coaching. You also coach your own group—are you able to discuss any technology you implement when coaching your own athletes?

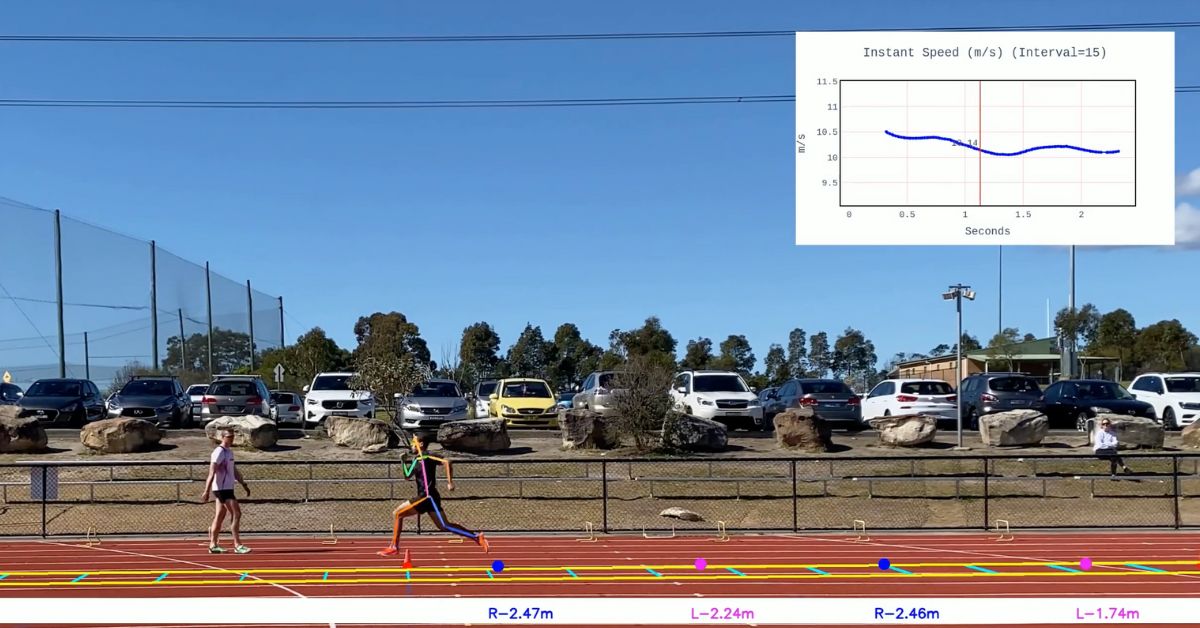

Vas Krishnan: Andrew Murphy uses a whole host of technology, and due to his success over a sustained period has federation backing that provides him access to these resources. Personally, I don’t have the same access, but have used things such as timing gates and VueMotion. I find the Artificial Intelligence predictive motion modelling helpful when an athlete has recurring injuries. For example, I had an athlete who had multiple hamstring strains on his right leg, but his strength assessments suggested that was not a limitation for him. VueMotion, however, was able to show us that he had an asymmetry in his stride, with some casting of the right shin, that was overstressing that hamstring. We then used this information to create technical and physical interventions to reduce the recurrence of the issue.

I tend to do quite a lot of video analysis on my iPhone camera, but I set it to 4K and 60 frames per second to look a ground contact times and numbers of strides to 10 meters. I use Hudl and Coaches’ Eye if I want to measure a specific angle or something like that, but it tends to be used to reinforce an idea I may have based upon what I’ve seen with the naked eye. In these cases, it’s essential that you know what to do with the information, that’s where the value lies. My personal feeling is that at the higher levels, this kind of analysis is primarily useful in understanding injuries and working to prevent them.

Video 1. Layover video from VueMotion, as seen in Figure 1.

In the gym, we do some velocity-based training, and to facilitate that we primarily use Enode Pro (formerly Vmaxpro) or Barbell Mate to provide information regarding time to peak velocity and maximum velocity within the movement.

Video 2. Athlete Jack Darcy performs pocket cleans.

Freelap USA: Is there much in the way of technology that you use from a medical perspective? Do you implement technology when assessing the health of an athlete?

Vas Krishnan: Generally speaking, there is probably a broader variety of technology I use in this domain. I’ll use various means to assess an athlete’s morphology, such as muscle bulk and circumference, and in the past have used DEXA scans as a way to assess an athlete’s body composition. However, this is something I have moved away from a little more now, because I think athletes can become obsessed with their weight and body composition to the point it can be detrimental.

If an athlete has a specific issue, such as a hamstring injury, then an MRI can provide me with information that may inform that rehabilitation approach and timeline. I use the British Athletics 0-4 grading system to classify the size of the tear.

- Delayed onset of muscle soreness.

- Tear less than 5 centimeters.

- Tear 5-15cm.

- Tear greater than 15cm.

- Complete rupture.

A, B and C are then used to identify the location of the tear within the tissue.

-

A Tear in the muscle belly.

B Tear at the musculotendon junction.

C Tear in the tendon.

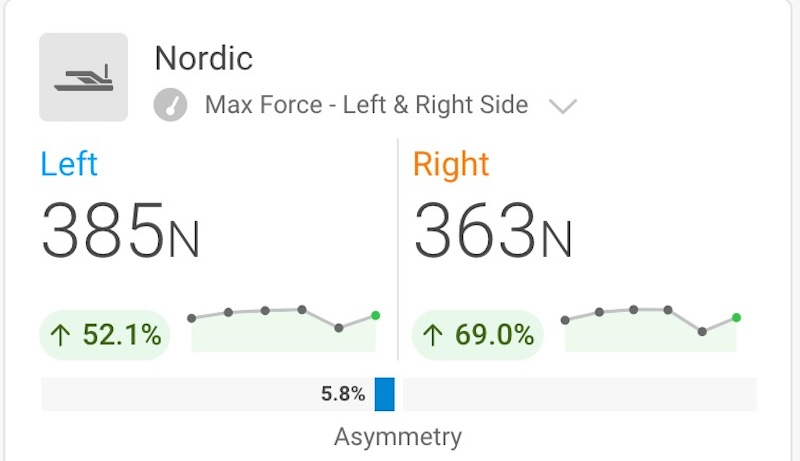

In a clinical setting, I will look at things like range of motion and use things like dynamometry and the Vald NordBord to assess strength imbalances. Although I don’t have anything to specifically measure reactive strength index (RSI) of hamstrings, I will always look at reactive hamstring exercises like Chinese Plank Switches, to see if there is discrepancy side-to-side. I like to look at eccentric strength in my athletes’ hamstrings when they are healthy, because should they get injured, I can then measure this again and compare.

When I know an athletes’ baseline numbers, I then have a tangible target to work towards and can try and implement interventions to encourage the physiological change I am after to return to baseline after an injury. The other use for this data is that it can help rule out the cause of an injury. If the strength has not really changed after an injury, then it’s likely that it’s not the cause of the issue.

I like to look at eccentric strength in my athletes’ hamstrings when they are healthy, because should they get injured, I can then measure this again and compare. Share on X

Freelap USA: What are the key technical aspects or positions you’re looking for with your athletes?

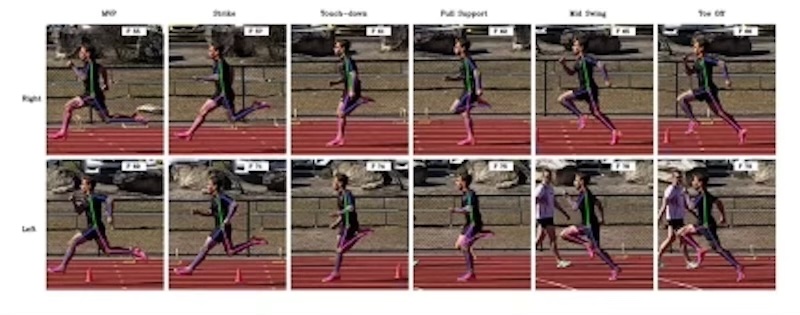

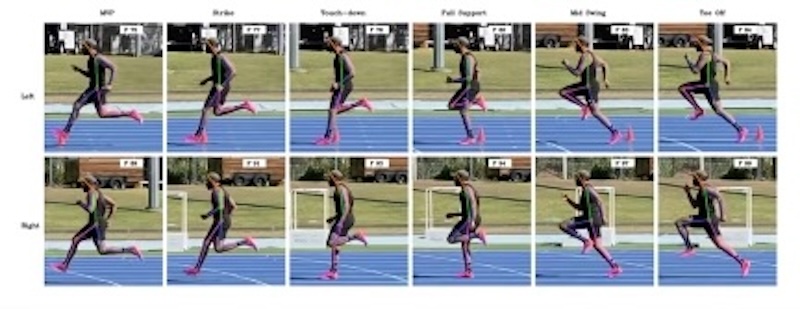

Vas Krishnan: I like to use a lot of the technical guidelines provided by Ralph Mann, and where I place my focus will depend on the athlete in front of me and their injury history. Some of the general positions I look for are:

- Figure or four at touch down (seen below in Figure 5 full support phase).

- Initiating ground contact very close to underneath the center of mass and controlled shin angles.

- I don’t want to see casting of the shin prior to ground contact, which may encourage a large touch down distance, which can place large stresses on the hamstring muscle group. Therefore, if an athlete has a history of hamstring problems, this will be an area of focus and it is cases like this where video analysis and platforms such as VueMotion can be particularly helpful.

- No excessive rear-side mechanics—if I’m watching my athlete from behind, I don’t want to be able to see the sole of their spikes. If an athlete has a history of issues with their hip flexors, then this will be an area of focus. Ensuring they have the required pelvic control to avoid an excessive cycling motion of the foot behind the body can help take stress of the anterior hip architecture.

- A high degree of hip extension during the stance phase, which will also allow for a high degree of displacement as the center of mass is projected.

- One thing I don’t particularly like is the cue knees up, because I think this can disrupt the posture of an athlete, causing more technical problems than it solves in many cases.

Freelap USA: Can you outline a typical week of training for your group?

Vas Krishnan: I program using 12-week macrocycles. The four macrocycles are:

- General preparation.

- Specific preparation.

- Competition preparation.

- Performance preparation.

Within each macrocycle, we have four 3-week microcyles, and they operate on a 2-week loading, 1-week de-loading schedule.

During the Competition Preparation, each of the running sessions—acceleration, maximum velocity and speed maintenance—each have two variations and alternate weekly. There is a plyometric driven acceleration session and a heavy sled driven acceleration session. There is a long top speed session (80-110m) and a short top speed session (60m). Finally, there is a short speed endurance session and a long speed endurance session.

A typical week during this phase of the year will looking something similar to the following:

Sunday – Maximum velocity.

-

Long variation –

2 sets of:

60 meters, fly 30 meters (50 meter build), 90 meters (the time of the 60 meter rep plus the 30 meter fly rep should equal the time of the 90 meter rep).

8 minutes between reps, 12 minutes between sets.

Short variation –

2×2-3x60m.

8 minutes between reps and 15 minutes between sets.

Monday – Maximum strength.

Tuesday – Acceleration.

-

Plyometric variation –

3 sets of the following complex:

Plyometric exercise to pit (e.g., broad jump or 5-bound), medicine ball throw, rope run, speed plyometric (e.g., speed hop), regular run.

The type of plyometrics used in this complex will vary, but some of the exercises that are often included are speed bounds, tuck jumps, and single leg hops.

Sled variation –

2 sets of the following complex:

Resisted run from a start without blocks, resisted run from blocks, non-resisted run from blocks, contested run from blocks.

Wednesday – Upper body, ancillary work and pool regeneration.

Thursday – Speed endurance/maintenance.

-

Long variation –

300, 200, 150, 100 or 3-4×200 or 200, 150, 200, 150

Typically, there would be around 10-15 minutes between runs in a session like this.

Short variation –

3-4x2x60-80m.

30 seconds to 2 minutes recovery between reps, 8-12 minutes recovery between sets.

Friday – Power gym, Olympic lifts, jumps.

Saturday – OFF.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF