John Nicolosi is a sprints coach working with a private group based in Melbourne, Australia. He has a Bachelor of Physiotherapy from Melbourne University and has completed a Master of Exercise Science (Strength and Conditioning) to complement his coaching accreditations. Nicolosi currently runs a sports performance and injury clinic in Melbourne. His approach to sprint coaching is to optimize training around the individual profile of the athlete.

Freelap USA: You come from a medical background and run your own physiotherapy clinic. How much does this influence your coaching, and what are some ways that you feel this benefits you as a coach?

John Nicolosi: It has its advantages and disadvantages at times. It definitely allows me to appreciate my background understanding of anatomy and physiology and view performance from a different perspective. However, I have to be careful not to bias my observations based on this lens.

I have slowly shifted to having some of my colleagues work with the athletes I coach more and more as I try to remove bias from the way I view any injury issues that they have. When you spend as much time with your athletes as I do, your professional relationship changes; some separation is needed to not unduly influence how you view what is occurring with their injury or performance.

Your hope as a coach is always to get the most out of a training session by drawing on your clinical experience to identify whether you’re taking a reasonable risk with your decision-making. Share on XThis probably sounds like I am making it out to be a negative, which is hardly the case. The benefits are significant. Overall, this type of background creates confidence for the athletes since you can assess and modify things based on what you see and feel and then make changes to their performance or injury picture in real time. Your hope as a coach is always to try to get the most out of a training session by drawing on your clinical experience to identify whether you are taking a reasonable risk with your decision-making.

The other major area of benefit is that the profession comes with an understanding that you are required to be a lifelong learner. This seems to be a trait of most good coaches. It can be an issue at times, as we tend to like tinkering with things as we learn them, but overall, it is definitely a good thing.

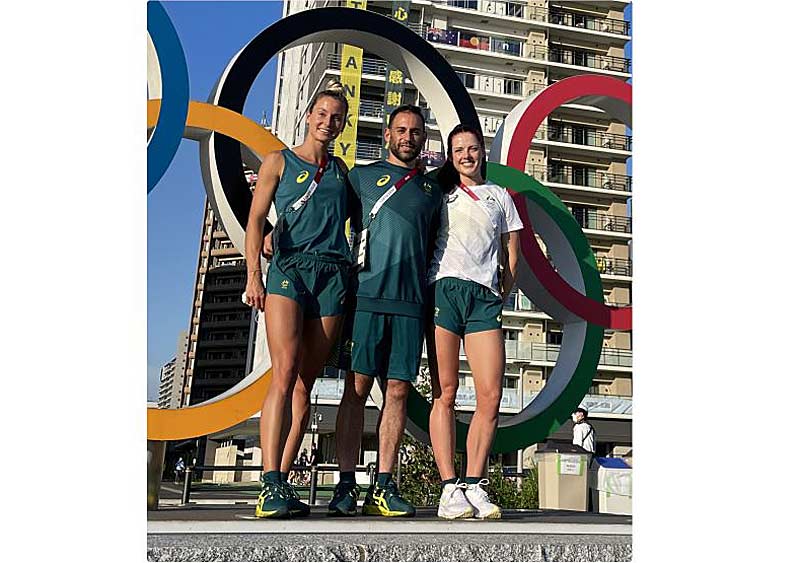

Freelap USA: Hana Basic made the Olympics in 2021, which was probably something not many would have predicted prior to the Australian domestic season that year. Were you surprised at how well 2021 went for her? What are some of the things you feel were responsible for the progress she made from pre-COVID-19 to Tokyo?

John Nicolosi: It was a surprise, but not for the reasons that some would see externally. There was never any doubt in our belief that Hana could perform to that level, and throughout that season, it was obvious to us where she would end up. The surprising part was that Hana was able to make the necessary adjustments to her professionalism when it came to her involvement in the sport, and COVID-19 was a huge accelerator of this.

The removal of distractions and opportunities for external events meant that she was singly focused on her training, and she ultimately received the benefits. So, honestly, from my point of view, the vast majority of the credit for the performance must go to her commitment and willingness to make such changes during a period that none of us enjoyed.

As to what factors led to the biggest changes on the track, the main training adjustment we made during this period was the use of race model practice with much higher frequency than in previous years. I’m sure that appears obvious on the surface. However, as a coach, I became infatuated with the concept of practicing race execution with a high level of precision, and the more often you do so, the greater your ability to perform such an execution under increasing levels of pressure.

I became infatuated with the concept of practicing race execution with a high level of precision…increasing the ability to perform such an execution under increasing levels of pressure. Share on XThis concept tended to permeate nearly every repetition we completed in training to create the foundation of race performance. I am still navigating this concept, but I do feel that there is a clear connection between getting the alignment of the skill acquisition with environmental and psychological features to allow the athlete to become increasingly comfortable with creating a defined performance. Speaking with classical musicians, the ability to perform a piece of music requires a level of repetitive practice but also the exploration of the performance across many different environments and different states of emotional attachment.

The hardest part appears to be creating the mindset needed for each athlete to nail this performance consistently. They all vary so much as people; thus, to have them nail their performance, you may need different tools, cues, and techniques to find what works for each person. In a broad sense, they are biomechanically required to meet a certain level of output. How that person gets there and what emotional state will foster the greatest learning and/or execution not only varies but can change over time.

Freelap USA: The timing of the Australian season means that athletes who go on to compete in Europe and at global championships can end up being “in season” for more than eight months. Do you find this a challenge, and how do you go about preparing for it?

John Nicolosi: While my experiences are certainly much more limited compared to other coaches, I view this as an issue of the choice of periodization model and approach to specific training. I was fairly heavily influenced by adapting some of Bondarchuk’s approach to planning and programming—the use of development periods interspersed throughout elongated racing cycles has proved invaluable. As long as you are aware of what features or KPIs are central to your athletes’ best performances, you tend to be able to maintain or grow them throughout the season.

A concept employed by many coaches that has been valuable to me is using race selection throughout phases of the season to develop characteristics of the athletes’ performances that are important for their ultimate competitions. This is typically the case with using indoor racing earlier in the year for Northern Hemisphere athletes.

For many of my athletes, I would say I am less influenced by the commercial realities of racing to make a living, and thus, we can choose races for overall season development. This may involve using a relay, specific track location, or competition to create the features I am after.

For example, I often spend much of our domestic season seeking out state and regional competitions that offer multiple rounds. While these competitions are not always helpful for fast times or commercial opportunities, they provide the ability to build the athlete’s capability to back up rounds. And given that the sport is shifting to repechage rounds in major championships, this may become even more important going forward.

Freelap USA: Are there any technical skills that you feel most sprinters struggle with? What key movements do you focus on a lot, and how do you cue these?

John Nicolosi: It tends to depend on the background of the athlete you are working with. However, I would say that acceleration skills, at least in Australia, tend to be poorly developed from a technical standpoint. That being said, elite maximal velocity mechanics and especially effective transitioning are always a challenge for some to get an understanding of how to sustain postures and kinetic outputs across these phases of the race.

In regard to acceleration, the ability to position the torso, shin, ankle, and upper limbs in adequate positions and project with clear intent does not always come naturally to people. So, the need to reinforce this over and over is a focus for many athletes I work with. There appear to be two major aspects to this equation. The first is having the physical capacities to generate the power needed, and the second is knowing how—and probably more importantly, when—to use these physical capacities.

I would say that I use a constraints-based approach for the development of acceleration skills, with step markers and resisted running as the primary sensory cues for the athlete to use as feedback. This gives the athletes instant information to judge against and often creates the ability to self-evaluate, which is a great skill for the athletes to pick up quickly. Getting them to feel these things and how they can differ depending on their approach to that individual acceleration is always good to observe.

The use of external feedback gives athletes instant information to judge against and often creates the ability to self-evaluate—a great skill for athletes to pick up quickly, says @johnnicolosi. Share on XTransitioning to top speed seems to be a major missing technical link for many athletes to be able to achieve their maximal velocity. Again, the use of external feedback from resisted sprints, external weighted clothing, and step markers appears to be helpful. In regard to cueing, Ryu Nagahara’s work has really helped the athletes understand that the shift from a desire to push horizontally to vertically happens in stages, and maintaining the horizontal pressure of ground contacts through this phase is extremely important if you want to hit your maximum capable velocity.

Freelap USA: Can you outline a typical “pre-season” training week for your sprinters?

John Nicolosi: It can vary depending on the person and the events they compete in, but as a general guide, it looks very similar to what many other sprint coaches do. As we get closer to the season, this often becomes very individualized and can vary from this quite a bit.

This is a guide for a short sprinter.

-

Monday: Acceleration and lower body power gym

Tuesday: Pool running and upper body power gym

Wednesday: Maximal velocity running or development (in the pre-season, this is usually more technical than near maximal) and lower body power gym

Thursday: Pool running and upper body strength gym

Friday: Acceleration running/acceleration power development

Saturday: Longer running—shifts from tempo repeats to speed endurance/special end across training cycles closer to the season; heavier lower body gym

Sunday: Off

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF