Core strength, along with defining the requisite anatomy, has been a longstanding topic of debate among strength coaches and practitioners. Despite the ambiguity and dismissiveness surrounding the subject, I have found significant value in emphasizing core strength with almost any athlete I’ve ever worked with. This became particularly evident during my time working with Navy SEAL personnel, who are often plagued by extensive injuries and movement limitations.

Regardless of sport or level of play, the core is essential for connecting and coordinating movements while also playing a primary role in transmitting kinetic forces, says @danny_ruderock. Share on XRelative to conventional athletes, regardless of the sport or level of play, the core is essential for connecting and coordinating movements while also playing a primary role in transmitting kinetic forces. In this article, I will cover specifically what the core is, why it is significant for sport performance, and, importantly, how we can get the most out of our training to improve core strength and function by utilizing the Keiser.

Defining and Understanding the Core

Anatomically, the core can be observed as any muscles, connective tissue, or fascia that attach to or act on the spine, rib cage, or pelvis. Collectively, these tissues act to flex, extend, rotate, or bend the adjacent appendicular skeleton and assist in connecting the upper and lower extremities.

From a functional sense, the core muscles are arranged in a unique manner and tend to have lower relative contractile capacities than the muscles of the arm or leg. Additionally, these are generally smaller muscles with smaller cross-sectional areas while also having a wider range of orientation and pennation angles due to possessing more precise mechanical actions. For instance, the quadratus lumborum (QL) and the transverse abdominis are essential core muscles and, despite their relatively low contractility, play a key role in stabilizing and integrating the pelvis and rib cage.

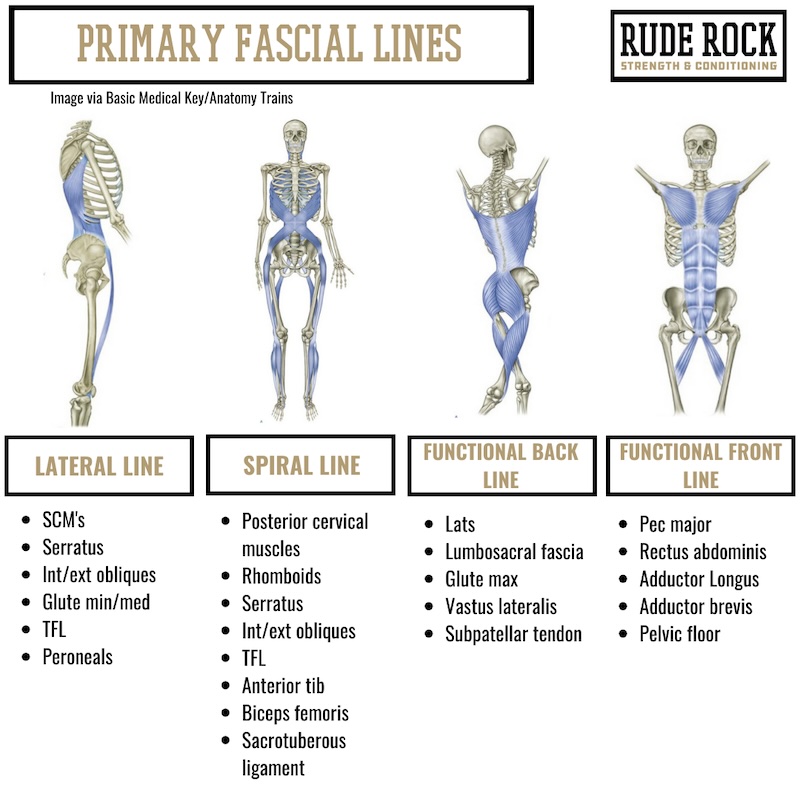

Another way of understanding core anatomy and function is by observing the body through a fascial lens, which is something I have discussed at great lengths over the years. As it applies here, the myofascial lines provide a perfect illustration of the direct interconnectedness of the human body and the integrative function of our anatomy—no muscle ever, in any case, works in isolation.

As shown in the graphic below, the primary myofascial lines include several crucial core muscles, such as the lats, adductors, glutes, and obliques. When we are able to get beyond the myopic view of independent muscles and their isolated actions, we can better see the demand for having multiple independent structures providing specific functions that contribute to a global pattern or outcome. This, in the purest sense, is how the core functions.

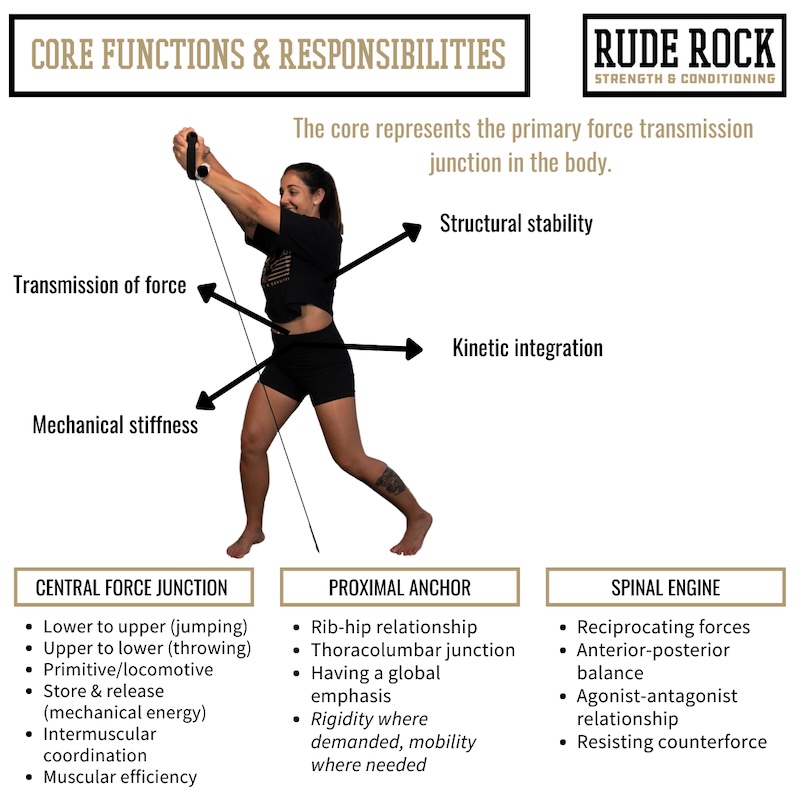

The function of the core is multifaceted, but it can primarily be seen as transmitting and connecting forces throughout the body. This requires some combination of resisting forces, managing reciprocating forces (torque), rotating, bending, and transmitting forces. Common and straightforward examples of this include coordinating hip and arm action during sprinting, maintaining pelvic stability during single-leg landing, and thoracic rotation and trunk reciprocation during throwing actions. Analyzing the core in this way should help to illuminate the parallels to the primary fascial lines and how this significantly expands the relevant muscle groups and movements that can be classified as core training.

You shouldn’t need me to tell you, but specific or isolated core movements like crunches, leg lifts, Russian twists, etc., should seldom, if ever, be utilized. The conventional applications of core training have very limited redeemable value for athletes. Rather than seeing core training as applying independent exercises, view core training as standard, global patterns that are modified to emphasize certain mechanical actions of the core. These standard patterns should simply reflect the actions and positions observed in sport.

For instance, as opposed to doing a standard Palloff press or static cable chop, integrate those actions into bigger patterns like lunges, locomotion, or bending. Having the athlete move from positions that are commonly experienced in sport while stressing the predominant vectors is really the boundary from which you need to work. And this is where the Keiser comes into the spotlight.

Benefits and Applications of the Keiser

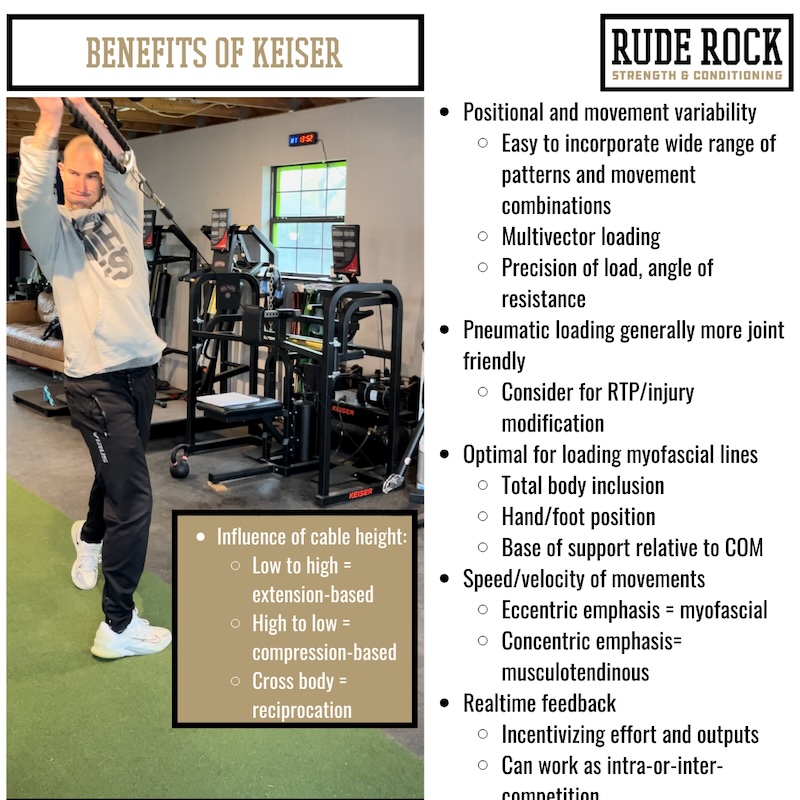

As I covered in a previous article discussing the Keiser for arm care, the overarching benefit to using the Keiser is the wide range of variability that it can add to the movements being performed. Additionally, the Keiser makes it very easy to replicate sport-specific positions, patterns, and vectors; by default, I suppose this is why I find so much value in using the Keiser for core training.

The ability to load multiple planes, patterns, and positions is essential for beneficial core training. When we can adjust the height and angle of the arms and utilize very precise loading, we can stress virtually any fascial line and/or muscle group. The dynamic fulcrum of the Keiser provides a means to load very specific patterns, which can be beneficial by allowing athletes to move through patterns or sequences that are more comfortable or effective.

While we want to see certain foundations of movement, an overemphasis on “perfect” weight room technique may become consequential for athletes. For this reason, I emphasize variability with Keiser movements for my athletes. I believe a foundational element of core training is having some level of reactiveness integrated into the training, and when using the Keiser, no two reps will be identical.

I believe a foundational element of core training is having some level of reactiveness integrated into the training, and when using the Keiser, no two reps will be identical, says @danny_ruderock. Share on X

The resistance type is another definitive feature of the Keiser equipment and an aspect that is beneficial for core training. As I’ve covered, transmitting forces and connecting movement patterns is the central function of our core. The pneumatic resistance mechanism allows athletes to accelerate completely through ranges of motion, something not possible with static loading. But, in doing so, we are able to stress the core at angles and ranges that just aren’t possible with most contemporary equipment or load types.

An important note here is also the significance of applying eccentric load to the core in these types of positions. The muscles of the trunk—obliques, transverse abdominis, QL, glute med.—are rarely eccentrically loaded during daily life, sport, or standard training. I have found a lot of value in applying eccentric tempos during patterns that stress these areas.

Amplifying Core Training with Keiser Movements

Collectively, between the positions, ranges, and vectors we’re able to work through, along with the pneumatic resistance type provided, the Keiser offers a premium opportunity for strengthening the core. While just a handful of the countless movements you can utilize for the purposes of core training, the six exercises listed below are the ones I tend to program frequently with my athletes.

Some general notes and framework for each of the following movements:

-

- Each of these can be considered an intermediate to advanced movement.

-

- They should be classified as accessory (Block 2–4) movements.

-

- They should be performed for 2–3 sets of 5–8 reps.

-

- These should be progressed through increased load, tempo applications, stressing new ranges/vectors, adjusting load placement or implement, or adding variability to combinations/movements.

- Although the Keiser can be seen as the optimal means for loading, you can effectively replicate most of these exercises with a standard cable or band setup.

1. Cross Row to Press

What I like:

- Controlling foot COP throughout transitions of movement.

- Reciprocating trunk (thoracic) action.

- Scapular demand/movement.

Video 1. Cross Row to Press.

2. Forward Lunge with Cross Chop

What I like:

- Spring action of back foot under load.

- Scapular demand/thoracic reach.

- Eccentric load on obliques.

Video 2. Forward lunge with Cross Chop.

3. OH Side Bend from Split

What I like:

- QL and oblique eccentric loading.

- Lateral line/lat stretch.

- Ipsilateral compression of rib cage.

Video 3. OH Side Bend from Split.

4. Dynamic Drop to Split

What I like:

- Rib-hip disassociation (dynamic).

- Thoracic reach.

- Hip IR/foot pronation control.

Video 4. Dynamic Drop to Split.

5. Curtsy to Lateral Lunge with OH Reach

What I like:

- Combination of lunge patterns (adductors/abductors).

- Thoracic-pelvic coupling.

- Loaded lateral hip flexion.

Video 5. Curtsy to Lateral Lunge with OH Reach.

6. Dynamic Rotational Extension

What I like:

- Loaded dynamic extension (safely).

- Closed chain hip internal rotation.

- High-velocity coordination.

Video 6. Dynamic Extension.

Keiser Is an Asset

Keiser equipment has become increasingly popular over the last few decades, and although it may not be a requirement for effective training and programming, it’s certainly a tremendous asset. As this applies to core training, there are several advantages to implementing Keiser for core work. Beyond the versatility, precision of load, and allowance of a wide range of vectors to move through, the Keiser permits the athlete to move intuitively and naturally in ways that best replicate the patterns observed in sport.

The Keiser permits the athlete to move intuitively and naturally in ways that best replicate the patterns observed in sport, says @danny_ruderock. Share on XFor all intents and purposes, Keiser work—especially core-specific work—can be viewed primarily as accessory options that are performed after your big/primary lifts. In some cases, such as return to play, we can utilize the Keiser patterns more as primary movements, but for standard cases, these exercises typically populate my later blocks.

I encourage you to be experimental with these patterns and, rather than just seeing increased load as the only route for progression, utilize an array of hand and body positions, movement combinations, and directions of applied load. You can progress and develop these movements in endless ways, and I believe coaches should prioritize this as they look to progressively increase the demands of core training.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF