The issue of recovery has moved to the forefront of athletic performance, especially after the articles written about how Lebron James spends the seven figures per year caring for his body. This, of course, sparked a lot of curiosity in athletes at all levels for ways they could recover more efficiently and feel their best as soon as possible.

We have seen an explosion in the number of available sleep trackers, massage guns, compression units, and other tools as athletes try to find the edge to help them feel better. I work in the high school athletics world, and I have seen more kids with their own personal massage guns in the last year than ever before. Many use these tools before games/practices to help them prepare their bodies, specifically on their calves and quadriceps with our fall sports.

I have seen more kids with their own personal massage guns in the last year than ever before, says @mgill52. Share on XI was given the opportunity to compare two of the compression units on the market—the Normatec 2.0 and the RecoveryAir from Therabody—as well as provide feedback on how they might benefit athletic trainers, specifically at the high school level.

Overview of Compression for Recovery from Exercise and Injury

For decades, compression has been a modality used in injury management, and it is the “C” in the acronym RICE (rest, ice, compression, elevation) long used by medical practitioners. It is commonplace to see an athletic trainer or physical therapist using a compression sleeve or ACE wrap to provide compression on an injured joint to help either limit or remove swelling caused by the injury.

Intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) has also been used as a modality in the medical field to help treat lymphedema and deep vein thrombosis and help in the swelling control of an injury. The Buyer’s Guide to Pneumatic Compression Recovery Systems does a great job explaining the history and uses of IPC in both the medical and athletic performance fields, as well as some of the benefits gained from IPC.

Now you see these units in every professional sport and most college athletic facilities to help those athletes perform at their best. Before using the IPC units I compare here, I used the Game Ready System, which provides compression and cold (through ice water) with varying attachments for different body parts. I found this unit to be helpful, but in my own practice, I have moved away from using cryotherapy as much and wanted to be able to provide intermittent compression without the added cryotherapy.

Product Comparison

I will start off with a comparison of the Normatec 2.0 and the RecoveryAir units (sold by SimpliFaster) and then discuss how I implemented them to help my athletes.

Normatec Leg Recovery System

- Price: $899

- 2-hour battery life

- 5 chambers (customizable using phone app)

- Bluetooth app control

- Works with all attachments (shoulder, hips, leg)

- 7 intensity zones (number 1–7)

- Zone Boost (provides extra time and pressure in a particular zone)

- 1 mode: Flush Mode

- Color display panel

RecoveryAir

- Price: $699

- 6-hour battery life

- 4 overlapping chambers

- Works with all 4-chamber RecoveryAir garments only

- Precise pressure control (manually adjust pressure down to 5-mmHg increments between 20 mmHg and 100 mmHg)

- Tailors pressure to size of an individual’s limb to prevent over-constriction

- FDA Type II medical device

So now that I’ve given you some of the specifics on each unit, let’s talk about the overall experience of using both units. Each is very well built and of high quality, and both units helped my athletes feel better post use—we used them weekly to help our football team make a run to the GHSA State Semifinals.

My coworker or I would offer recovery sessions during our weekend injury checks. These sessions typically consisted of 20–25 minutes on one of the compression units, followed by an ice bath if the athlete wanted it. We limited the use of the units to varsity starters, and we also gave preference to those who played both sides of the ball. We also offered sessions with the compression units after practice throughout the week leading up to the game.

Could we have done this with our Game Ready Systems? Possibly, but the model we have for the Game Ready only works with one limb at a time, and the attachments are broken up into body parts such as knee, ankle, hip, and shoulder and not an entire lower or upper extremity attachment. The Normatec and the RecoveryAir allow one or both limbs to be done at a time and go from the ankle all the way up the thigh (or hand all the way to the shoulder, in the case of the upper extremity attachment).

The feedback from the athletes was overwhelmingly good, and the systems helped the athletes feel better sooner after using the compression units compared to when they didn’t. This meant that Monday practices could be more effective since the athletes were not fighting through the residual soreness of a physical Friday night game.

This meant that Monday practices could be more effective since the athletes were not fighting through the residual soreness of a physical Friday night game, says @mgill52. Share on XWe also saw a positive effect on performance with our cross country runners. We applied the compression units the day after one of their tougher workouts in the week leading up to a meet. In fact, one weekend we saw three athletes PR (by an average of 42 seconds), and the other two were a second or two off their PR.

We are excited to see how we can help our spring athletes (baseball, soccer, lacrosse, and track) recover better and hopefully see better performance.

What Separated the Two Units?

It was the small details that I found different between the two units, leading to preferred uses for each.

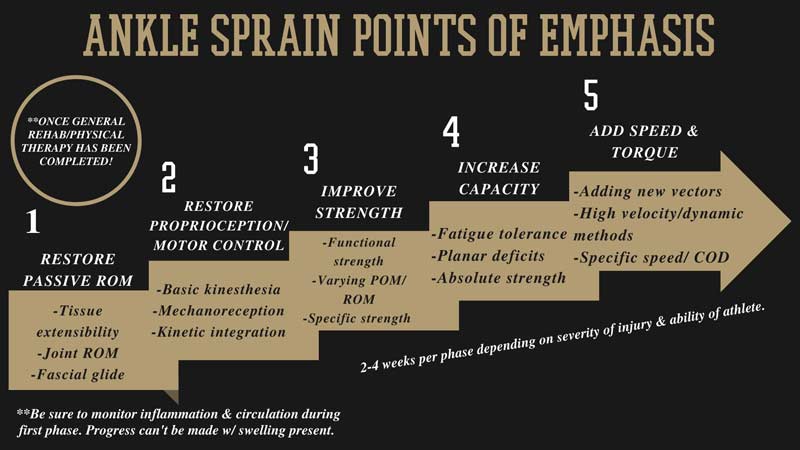

The Zone Boost option on the Normatec is great for those who might use the entire compression garment but want a little extra love on their calves or feet, for instance. I also found the ability to limit the number of chambers being used as perfect for the athletic trainer treating an ankle/lower leg injury and wanting to see more cycles performed on those specific areas. Instead of treating the leg as a whole, the Normatec’s ability to localize the treatment to the lower leg and ankles allowed us to focus the treatment on the injured area, specifically with ankle sprains. The Normatec was my preferred option when it came to injured athletes.

The RecoveryAir brought a more tailored experience as far as the amount of pressure it provided for the individual. The unit is said to use exact pressures based on the size of your limb within the sleeve to help prevent over-compression. Over-compression can cause discomfort and even some numbness and tingling in the limb below the area being compressed. There were times when my athletes used one of the Normatec’s higher intensity levels and it became uncomfortable, but you can quickly and easily fix this by picking a lower intensity level on the compression unit.

Anecdotally, I did not experience any discomfort with the RecoveryAir, nor did I have any athletes mention discomfort. I also personally like the feel of the overlapping chambers, which give a bit of a spiraling feel as the constriction moves up your leg. The Recovery Air also has a more gradual feel as it moves up the leg compared to the Normatec, where it fills each section individually.

Choosing the Right Option

Overall, I think both units are good, and I saw results from them both. If I am solely looking for recovery purposes, I would go with the RecoveryAir. The price range helps here, but the compression also felt smoother and more sequential as it moved up your leg, whereas the NormaTec chamber-by-chamber approach felt a bit choppier. The overall experience, both mine and that of others who used the units, was also more enjoyable with the RecoveryAir.

I would go with the RecoveryAir if you’re using compression for recovery purposes, while I have found the NormaTec to be a more versatile unit for those who work in a sports medicine setting. Share on XBecause I work in a medical role, I want the capability of more targeted compression to help in injury recovery (specifically with ankles), while also having the ability to use compression for recovery purposes. I personally found the NormaTec to be a more versatile unit for those who work in a sports medicine setting at the high school or college level.

As I said before, both units are great, and we saw results with both. It all depends on the reason you’re using it—whether it is just to help you or your athletes recover faster, or if you need more versatility with the unit than just recovery.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

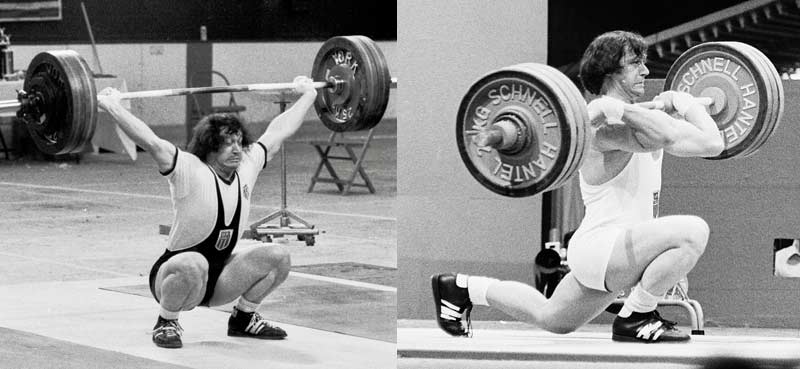

Kim Goss has a master’s degree in human movement and is a volunteer assistant track coach at Brown University. He is a former strength coach for the U.S. Air Force Academy and was an editor at Runner’s World Publications. Along with Paul Gagné, Goss is the co-author of Get Stronger, Not Bigger! This book examines the use of relative and elastic strength training methods to develop physical superiority for women. It is available through Amazon.com.

Kim Goss has a master’s degree in human movement and is a volunteer assistant track coach at Brown University. He is a former strength coach for the U.S. Air Force Academy and was an editor at Runner’s World Publications. Along with Paul Gagné, Goss is the co-author of Get Stronger, Not Bigger! This book examines the use of relative and elastic strength training methods to develop physical superiority for women. It is available through Amazon.com.