Conjugate training was made famous by Louie Simmons and Westside Barbell’s training method. Although his system is a concurrent system, conjugate is a piece of the Westside training method. Conjugate training simply means we rotate movements in and out of our program every week.

I’ve applied the same concept to our jump training. Just like we rotate bars or variations for max effort exercises, we’ll rotate our vertical and broad jump variations every week. By doing so, this exposes athletes to a wide variety of jump positions, which improves technique, surfs the force-velocity curve at a variety of joint angles, and creates a fresh stimulus.

How Did We Get Here?

When I began measuring jumps, I did so for the sole purpose of measuring readiness. As a byproduct, we were “working on jumping,” but we weren’t truly training the jump. We performed vertical, hands-on-hip (HOH), and pause HOH jumps. These were the most common jumps used for readiness and key performance indicators (KPI) to evalute program effectiveness. After taking enough data, I found these jumps were great tools to measure readiness and somewhat useful for program effectiveness; however, they left more to be desired because we weren’t truly developing the jump or getting the full picture of jump performance.

As I continued to measure these three jump variations, I found athletes weren’t “all-in” when performing the jumps daily or weekly. There were plenty of days athletes were excited to jump, typically leading to personal records (PRs), but also plenty of lackluster days. The monotony of doing the same jumps reguarly can lead to a lack of effort if we’re not careful. Can we use these jumps as a way to evalute readiness? Absolutely. But, over time, the athletes may not put in the same effort as they did in the beginning, leading to inconsistent results. The same argument can be made about readiness surveys, but I digress.

The monotony of doing the same jumps reguarly can lead to a lack of effort if we’re not careful, says @coachrgarner. Share on XThe next issue to consider when measuring jumps is the psychological impact of a poor jumping day. For some athletes, if their jump is down, their energy and mood is going to be off for the rest of the day. They’ll blame mistakes in practice or the game on being tired, instead of focusing on the task at hand. Not always, but it can happen.

I’ve had athletes that weren’t feeling their best yet still manage to excel in training or on the field. I’ve seen awful readiness scores using heart rate monitors, then athletes jump a PR. Fatigue is too complicated to be assessed and summarized by a single jump, and it’s important we communicate that with our athletes when performing jumps regularly.

Ultimately, I want to avoid the psychological impact of a poor jump performance, while also chasing performance increases and developing the jump weekly. This led me to using multiple jump variations over multiple weeks, which eliminated the obession over one jump output. I’ve found this develops a better jump profile and teaches athletes how to perform the skill of jumping through a part-whole approach.

Weekly Jump Layout

The basis of this system is rotating broad and vertical jump variations each week. In a typical week, our athletes perform one broad and two vertical jump variations. By rotating these variations, we’re giving our athletes the opportunity to hit PRs multiple times a week or month. This keeps the athletes coming back for more, as they’re chasing the dopamine hit of a PR.

Depending on how we organize a five-day training week, we’ll have one or two days of broad jumps and three or four days of vertical jumps. I prefer having more vertical than broad days because:

- Vertical jumps are harder to master;

- We can create more variations comparatively; and

- They give us a better picture of how the athlete is adapting and feeling.

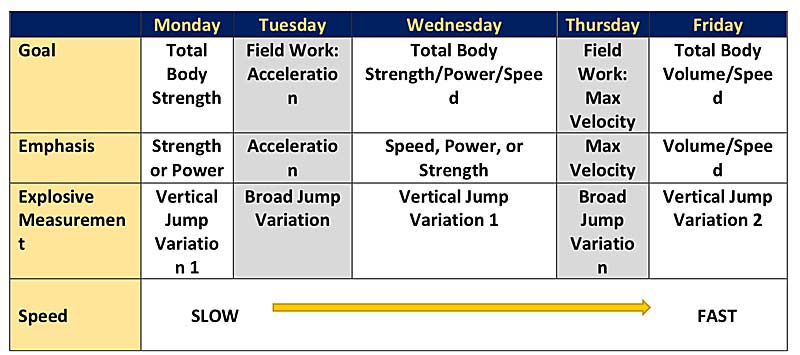

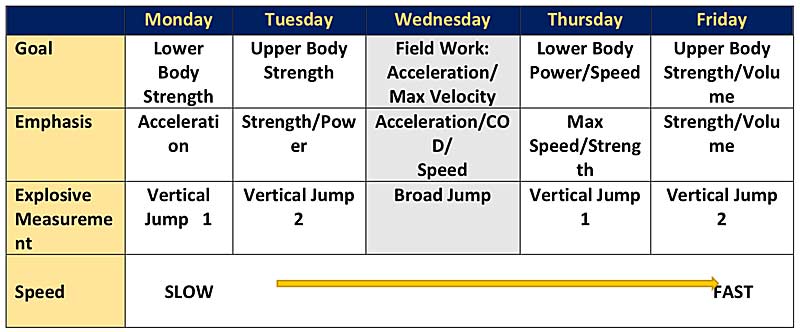

Below are some examples of how we can arrange jumps within our training. In a normal training week, we’re working slow to fast, with the emphasis going from acceleration to max velocity. Table 1 is an example of three days in the weight room and two days of field work. Table 2 is an example of four days in the weight room and one field day. These are common layouts of training weeks, but it can be manipulated to fit our unique situation.

I prefer to pair vertical jumps with weight room days because the majority of weight room movements have a vertical emphasis. On field days, we’re training acceleration and developing qualities or skills for sprinting and change of direction (COD). For those reasons, the broad jump makes the most sense because it aligns with the horiztonal emphasis of the day. Even though top-end speed (max velocity) has a vertical emphasis, acceleration and COD requires horizontal displacement.

Vertical and Broad Jump Variations

When I began using this system, I performed four vertical and broad jump variations: seated HOH, seated, standing HOH, and standing jumps. This created four-week cycles (weeks before repeating the same variation) that naturally fit into our training system. Over time, I’ve expanded the jump library to create a longer jump training cycle. I’ve found these additional variations enhance our adaptations and improve our athletic potential.

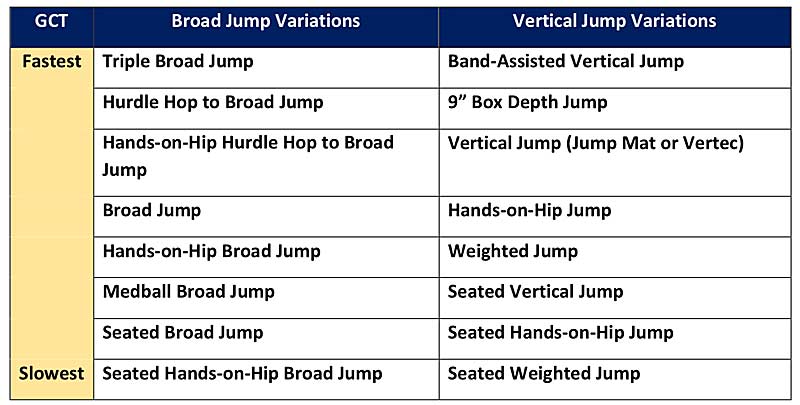

I’ve found that additional variations enhance our adaptations and improve our athletic potential, says @coachrgarner. Share on XThe key to this system is rotating jumps every week in a deliberate progression (think part-whole theory). Table 3 lists the jump variations I currently use with our high school population. This differs from the dryland training table because I’ve adapted the system to my current situation. The jumps are also arranged slow to fast in terms of ground contact time (GCT) because we’re moving from strength to reactive in nature.

As the coaches, we can add or take out any variations to adapt it to our situaiton and make cycles as long or short as we’d like. The idea is that every time we come back to a specific variation, our goal is to jump a PR. This may not happen every time, but it should happen more often than not.

If you look at Table 3, you’ll notice we’re progressing from seated to standing variations. This is because it lowers the learning curve for novice jumpers while progressing from a strength to speed (reactive) focus. Seated variations give athletes more time to put force in the ground and take out the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC). By taking out the SSC, most athletes will jump higher, as it favors strength-dominant athletes and lowers technical hurdles. Standing variations require athlete’s to use the SSC to quickly reverse momentum and put force in the ground. Our fast-twitch athletes shine here because they don’t need significant time to exert power.

Seated jump variations give athletes more time to put force in the ground and take out the stretch-shortening cycle, says @coachrgarner. Share on X[vimeo 664084958 w=800]

Video 1. Vertical Jump Variations (missing HOH and Verical Jumps).

[vimeo 664087383 w=800]

Video 2. Broad Jump Variations

For novice athletes, performing jumps in general will increase their vertical. Jumping is a new skill and fresh stimulus, and their technique will improve week after week. With this system, we set these athletes up for success by lowering the technical barrier with certain variations. For example, by performing seated or hands-on-hips jumps, we’re taking out technical factors—such as syncronizing arms with takeoff—that can impact jump performance. By using a part-whole approach, athletes only need to think about a couple technical pieces when jumping which improves the learning process.

For experienced jumpers, we must provide unique and varying stimuli to induce change. These athletes have jumped their entire lives, and having them perform the same jump week after week won’t give us the same return on investment (ROI) as unique jump variations. They’ve maxed out their motor pattern development, their neural pathways are highly-formed, and if we’re asking them to perform the same jump every day, frankly, they’re going to get bored.

Intent is a key element of jump performance, and a bored athlete won’t train with intent. By “taking away” the vertical jump for eight or more weeks, athletes will be chomping at the bit to see, test, and measure their vertical. It’s like keeping a race horse in the stalls: when we give them a chance to race, they’re going to give it everything they’ve got.

Intent is a key element of jump performance, and a bored athlete won’t train with intent, says @coachrgarner. Share on XIntegrating Conjugate Jumping into the Workout

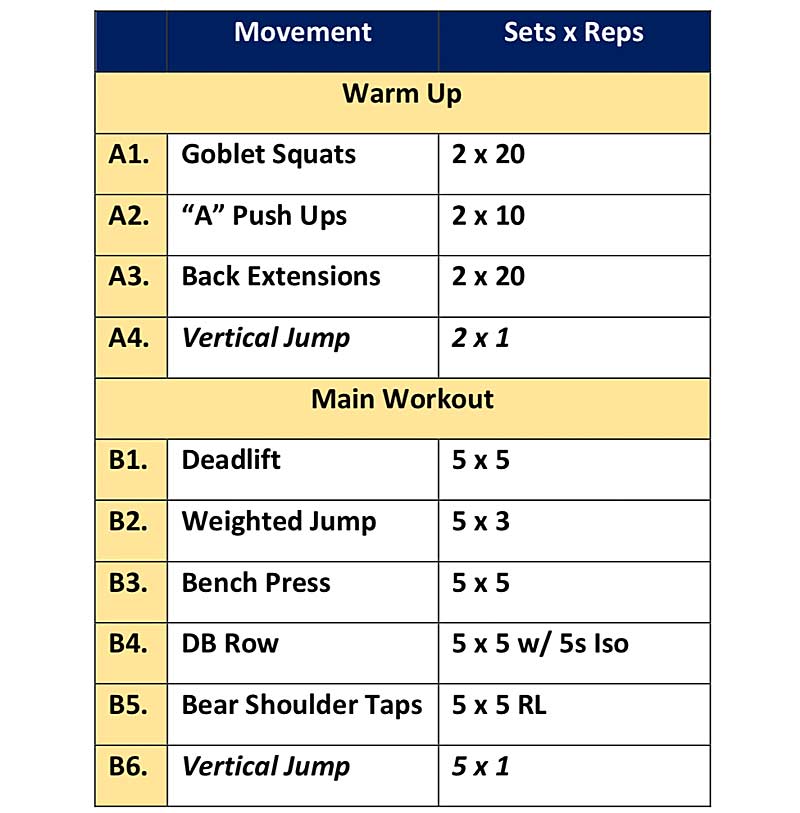

Integrating the conjugate jump system into training is simple because we can make it part of our warm-up, workout, or both. This all depends on the structure and flow of our training session. I typically run workouts in a circuit fashion with a multi-station warm-up. I’ve used circuits like Cal Dietz’s “Performance Circuit” and three-station supersets. This lends itself to seamless integration for jumping because it becomes a station. Typically, athletes will perform five to seven measured jumps a day. By the end of a week, this gives us 25-35 high quality data points to assess our program and athlete readiness. If an athlete jumps the majority or all their jumps over their previous PR, then we know we’re making significant progress.

If you have access to a jump mat, simply put it out with a sheet of paper and let the athlete’s record their jumps. Then we’re able to coach the room instead of recording numbers. For broad jumps, we’ll need to record the athlete’s jumps unless we have an intern or assistant coach in the room. If we trust our athletes, we can have them record each other’s broad jumps.

Another layer we can add within this system is aligning our training loads and movements with our jump variations to further emphasize a specific goal of the day. For example, I pair broad jump and squats together because they’re quad-dominant movements. I pair vertical jump and deadlift together because they’re a reflection of nervous system readiness and the deadlift will potentiate the central nervous system.

We can also align jump variations with our training loads to reflect speed or strength emphasis. During certain portions of the year, I’ll expect jumps to decrease, such as during a heavy eccentric phase, but then supercompensate six to eight weeks later. This keeps strength and conditioning coaches accountable because the data tells us if our program is doing what we say it’s doing.

During certain portions of the year, I’ll expect jumps to decrease, such as during a heavy eccentric phase, but then supercompensate six to eight weeks later, says @coachrgarner. Share on XThe biggest benefits of measuring a jump every workout is it creates competition in the room and shows our athletes they can hit a PR even when they’re tired. Everyone is trying to out jump somebody, which leads to high intent every jump. Psychologically, it’s a massive confidence boost when our athletes jump PRs on multiple sets or during their last set of the day.

In terms of readiness, we’ll be able to see where the athletes are for the day, week, and month. As the strength and conditioning coaches, it’s our job to let the sport coach know if numbers are negatively trending so they can adjust accordingly. On top of that, we can change the workouts as needed when we see significant drops over time. By tracking numbers every session, we can also autoregulate training if we so choose.

At the high school level, we can see how jumps are impacted by specific sports and when seasons change. I’ve found at the beginning of each season, athlete jumps decline because they’re in a new sport. A new sport means new stresses, and the coaches are typically training the kids to “get them in shape.” By tracking daily, we have objective numbers to show coaches that our athletes are struggling to perform at the beginning of the season due to an acute spike in load. By the time they’re adapted and recovered, we’re almost a third of the way into the season. If I’m the coach, I want my athletes to be ready to perform the first game, not a month later.

Results

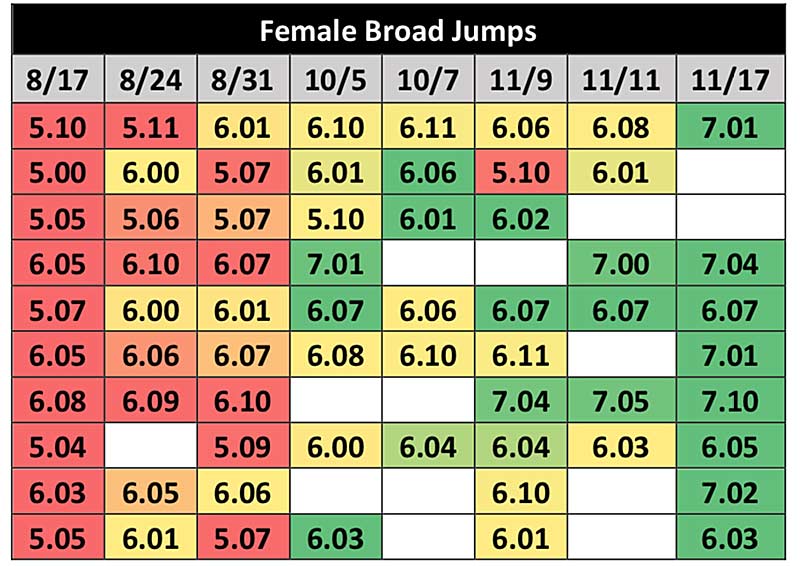

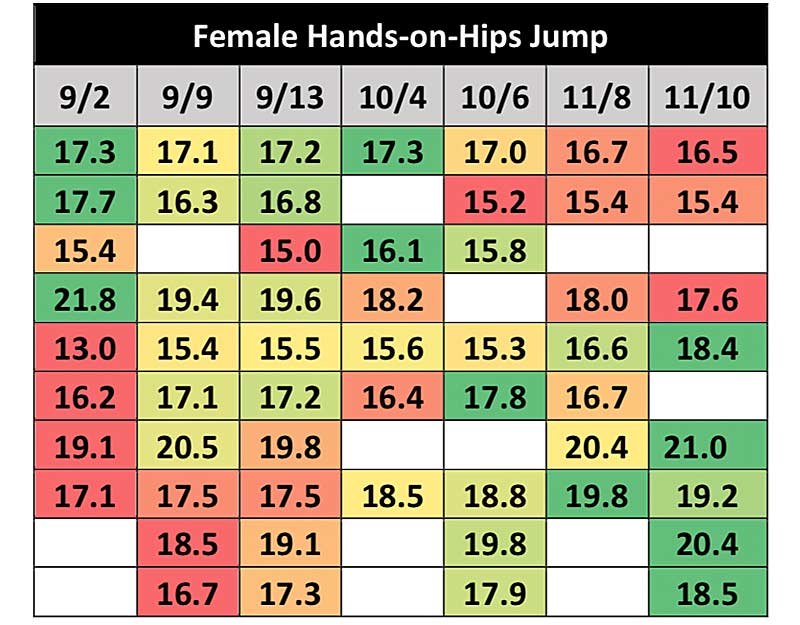

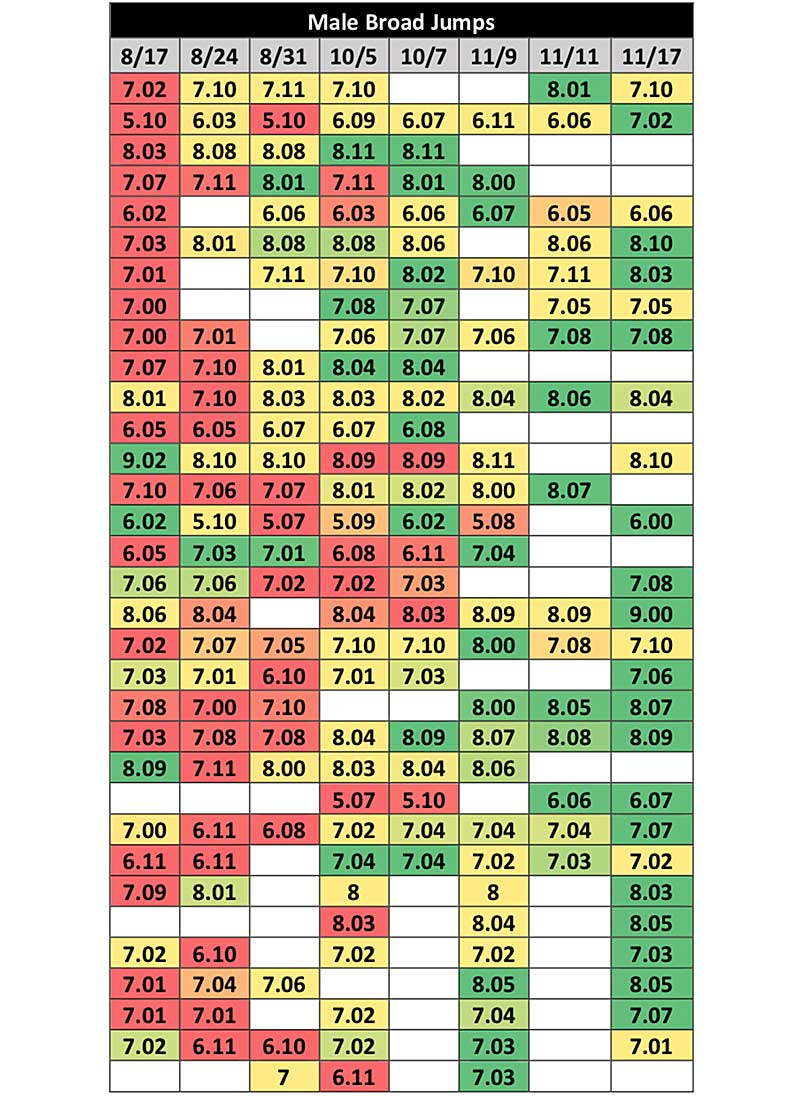

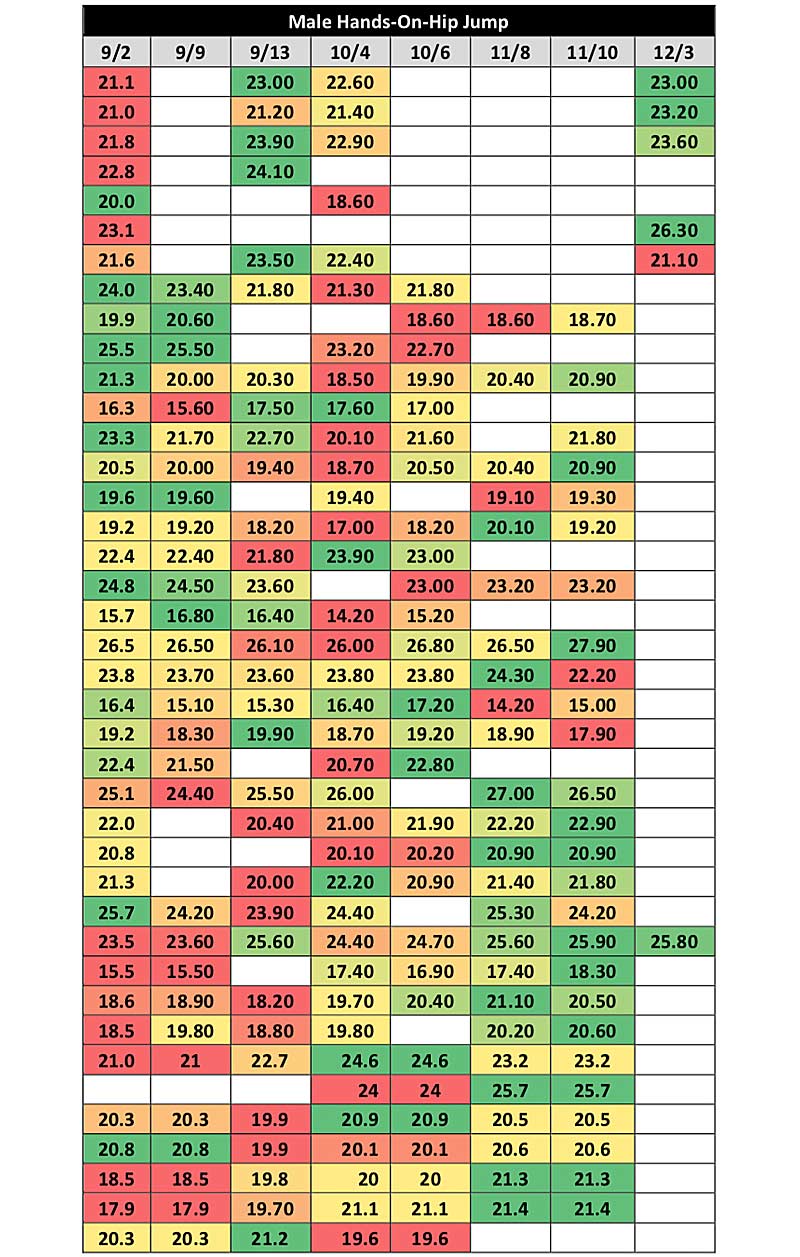

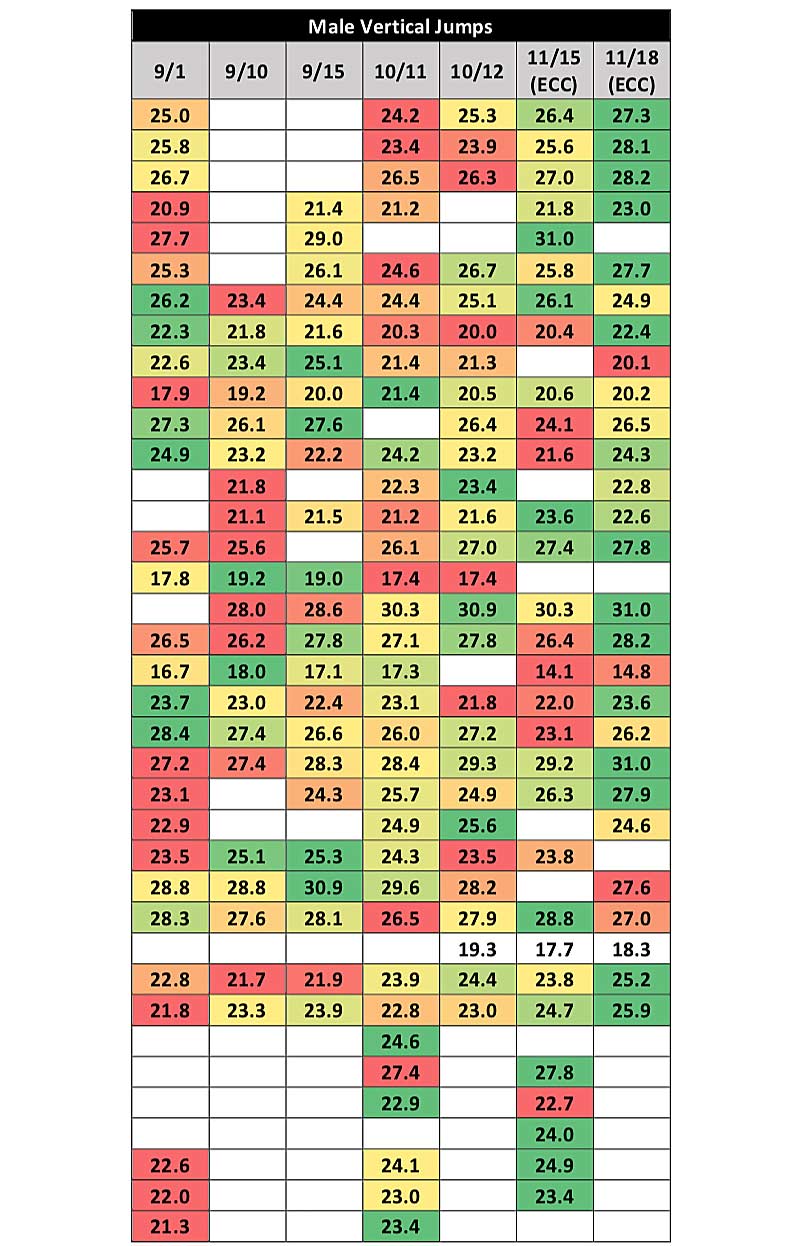

Below are the charts of every broad jump, HOH jump, and vertical jump I’ve taken with my high school athletes this year. I value the HOH jump more than the vertical because it accurately reflects the true power and fatigue of the legs. I view this as our floor of jump potential. The vertical jump has a greater technical requirement which causes greater variability until the athlete’s technique is dialed in.

In 12 weeks, male and female athletes improved their broad jump by 8” and 13” respectively. For male athletes, the average vertical improved from 24.3” to 25.1” over 12 weeks. Their HOH jump improved from 21.1” to 21.6” over 9 weeks. Our female athletes improved their vertical from 19.3” to 20” and their HOH jump from 17.2” to 18.2” over 12 weeks.

For the female athletes (Tables 5, 6, and 7), most were jumping PRs as we circled back to the specific variations. I believe this is because they were learning how to jump, but most importantly, they were learning to be explosive and move with intent—which might be the most important skill for them to learn within our setting. On top of that, most of my female athletes had never trained, which led to a heightening of their nervous system.

Looking at Tables 6 and 7, notice how the HOH and vertical jumps are trending downward for the athletes at the top of the chart. These athletes transitioned from explosive fall sports to soccer, and one was out for a month due to illness. For those on the bottom half, most transitioned to off-season leading to improved recovery. As previously stated, we can track readiness and watch how seasons and specific sports impact outputs.

We can track readiness and watch how seasons and specific sports impact outputs, says @coachrgarner. Share on XWith the male athletes (Tables 8, 9, and 10), there’s a greater fluctuation in jump numbers. For the broad jumps in Table 7, their skill and technique for the broad jump improved drastically which led to PRs. Yes, there’s going to be inter- and intra-muscular coordination at play, but technique is a significant driver here.

In Table 9, the athletes in the top half of the chart have either just ended fall sports or are starting winter sports. Naturally, as the season progresses, we’ll likely see a downward trend due to fatigue. For the bottom half of this chart, the majority of these athletes don’t play a fall sport and are adapting to the training.

Conclusion

The conjugate jump system is a customizable system that is effective for both novice and experienced jumpers. We’re able to improve technique, provide a unique stimulus, and track readiness throughout the year all in one system. This system helps build buy-in and gives athletes daily opportunities to chase PRs. The more often our athletes can set new PRs, the more they’ll want to train. The beauty of this system is that we can individulize it to our situation, program, and athletes. As long as our variations build upon one another, we can be as creative as we’d like and customize it to our training philosophy.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF