Swimming is a unique sport that poses a challenge for strength and conditioning coaches. It’s one of the few non-land-based sports in the collegiate or high school setting, and most—if not all—of our knowledge and experiences tend to be based on dryland sports. Still, swimmers need to develop the same performance qualities as any other athlete, and just like we trust them to perform their best when it counts, they trust us to rise to the challenge.

A quick online search on “dryland training” provides workouts centered on developing endurance through high repetition sets or intervals—this is the most common trait swim coaches want to develop, but it quickly becomes redundant if it’s the only quality we’re training for week after week. Eventually, we’ll reach a point where our focus on endurance takes over and speed and power fall out of focus. To develop a healthy and successful swimmer, we must pursue multiple performance qualities in and out of the water with the end goal of swimming faster times.

Speed vs. Endurance

Endurance is the enemy of speed. The more effort we pour into endurance, the more speed we take away. If you’re a short-distance swimmer, speed has a greater impact on performance than endurance. Is endurance valuable? Absolutely, but it is highly trainable and is retained over longer periods of time compared to speed or power. Our speed bucket needs to be deep and refilled weekly. Therefore, short-distance swimmers will find it beneficial to train with the High-Low Swimming Model in and out of the water.

Most swimmers have never trained with the goal of improving athletic performance. With this model, the goal is to improve movement proficiency, performance outputs, and the aerobic base. These qualities will reduce their risk of injury, improve speed, increase stroke rate, raise power outputs, and increase the efficiency of the cardiovascular system.

For swimmers, movement proficiency isn’t typically hindered by a lack of flexibility but a lack of motor control and coordination, says @coachrgarner. Share on XFor swimmers, movement proficiency isn’t typically hindered by a lack of flexibility but a lack of motor control and coordination. Most swimmers haven’t been exposed to sprinting, jumping, or the foundational movement patterns for land-based sports. Why is that exposure important for swimming? By improving coordination and motor control, we can limit injuries through an effort to eliminate improper movement patterns and increase joint stability, all while improving performance outputs.

Performance outputs refer to the speed, power, and strength qualities commonly pursued within the weight room setting. These qualities improve our swimmer’s ability to produce speed and power coming off the blocks, while turning, and through the water. These will be trained through sprints, jumps, and resistance movements.

Developing the aerobic base is arguably the first performance quality we should pursue—if swimmers don’t have a substantial aerobic base, they will not have the capacity to train at a high level, recover quickly, or handle multiple races in a day. Once this has been established, we can pursue maximal outputs and train their aerobic system as needed.

Weekly Layout and Training Frequency

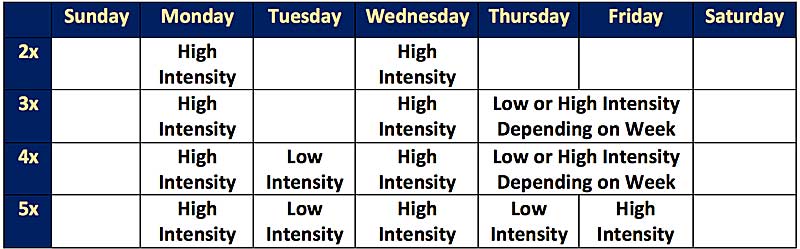

During the week, we alternate between high- and low-intensity days. Training frequency dictates what type of training session we perform day to day, as shown in figure 1. We can move the training days to reflect our schedule, but the key is to keep high-intensity days 48 hours apart.

For 2-3 dryland sessions a week, I suggest performing strictly high-intensity days unless your swimmers need to recover or improve their aerobic base. Early in the season, developing a robust aerobic base takes priority over max outputs. For 4-5 sessions, we alternate between high- and low-intensity days. For four sessions a week, the performance coach decides if the fourth day needs to be high or low based on their swimmers’ needs at the time.

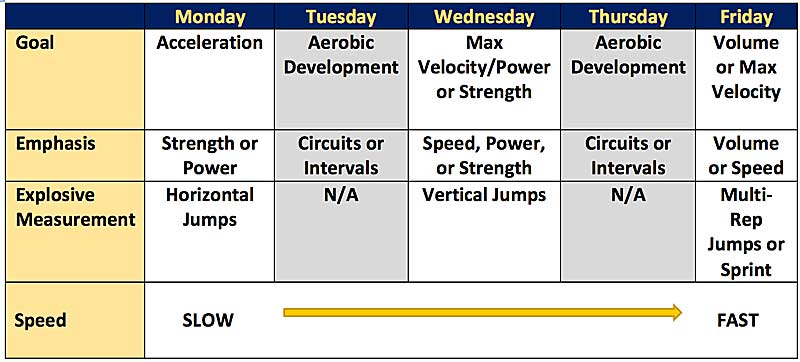

Training Slow to Fast

As we progress through the week, dryland training goes from slow to fast in terms of emphasis. By doing this, we prime the nervous system to be ready for the rest of the week, which is a concept discussed by Cal Dietz in “Triphasic Training.” Monday is not the best day to perform max speed or strength work because the body will be sluggish from the weekend. Instead, we can use the beginning of the week to prepare the body for the more intense sessions later in the week. This will lead to higher-quality speed or strength sessions.

Starting Monday, we focus on acceleration. This means our first high-intensity session has a strength and/or power emphasis. Wednesday’s focus is max outputs: velocity, power, or strength. If we have a third high-intensity day, this is either a volume or speed day depending on the previous session, time of year, and training goals.

Wednesday, or the second high-intensity day, is the session we can hit hard. Focus on one quality for the day or train two qualities, such as speed/power or power/strength. Avoid combining speed/strength because they are on opposite ends of the spectrum. Speed requires fast muscle contractions, while strength requires drawn-out or slow muscle contractions (relatively speaking). Power can be trained on either day because it sits between these two qualities.

In season, I suggest performing strength on Monday, speed/power on Wednesday, and then max velocity on Friday. This way, you are truly working slow to fast to prepare the body for weekend meets. You want to make sure your strength work is far away from race day while speed work is close to race day.

Developmental Jump Program

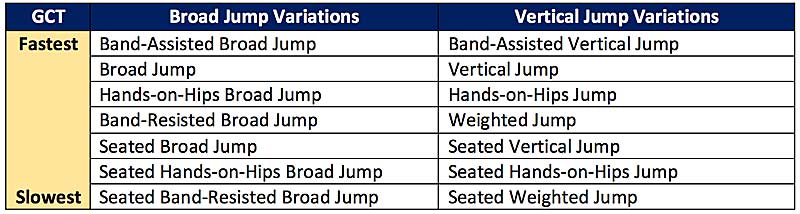

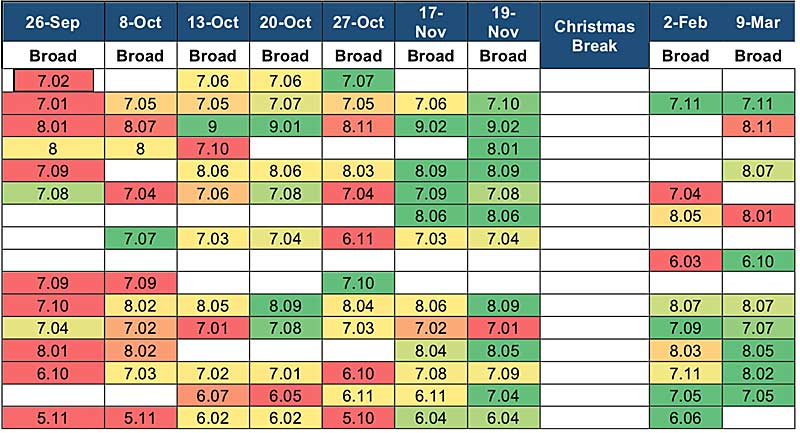

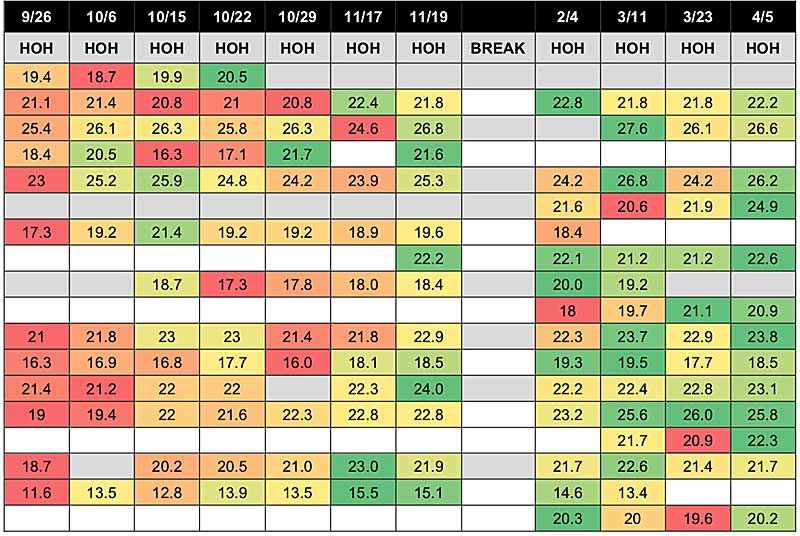

A significant part of our dryland training is incorporating jumps into every high-intensity workout. This includes multi-jump and single jump variations. We perform a minimum of four broad jump and four vertical jump variations in a month, which are measured each workout. Following the same concept as our weekly layout, we progress from our slowest to fastest jump in terms of ground contact time (GCT) each week.

The idea is that our jump variations surf the force-velocity curve and teach our swimmers to be powerful from a variety of positions and joint angles. This improves body awareness and inter- and intramuscular coordination and leads to greater intent coming off the blocks or turns in the water. Furthermore, this aligns our jump variations with the goal of the day, adding to our overall stimulus.

Our jump variations improve swimmers’ body awareness and inter- and intramuscular coordination and lead to greater intent coming off the blocks or turns in the water, says @coachrgarner. Share on XBy the end of each workout, our athletes will have 7-8 measured jumps. This also gives us the opportunity to autoregulate training if we desire. Typically, my athletes PR between the fourth and eighth jumps of the day. As coaches, we know this is due to potentiation, which leads to higher outputs in the long run. Psychologically, this builds tremendous confidence and buy-in because they’re jumping higher when they think they should be jumping lower.

On average, after implementing this program our broad jumps improved 8 inches and hands-on-hips jumps improved 3.6 inches over the course of six months (including five weeks off for winter break), and this was even during COVID-19. Six swimmers improved their broad jumps by 10+ inches and four went up 12+ inches. For the hands-on-hips jump, four swimmers improved by 4 inches or more. Did improvements in technique play a role? Absolutely, but we don’t improve our broad jump by more than a foot with just improvements in technique.

Practical Applications: The Performance Warm-Up

The goal of the warm-up is to improve the resiliency of our athletes and prepare them to perform. We combine prehab movements with total body movements to increase body awareness, muscular coordination, and human performance while improving resiliency. Think of the warm-up as an opportunity to stimulate performance and microdose athletic movements.

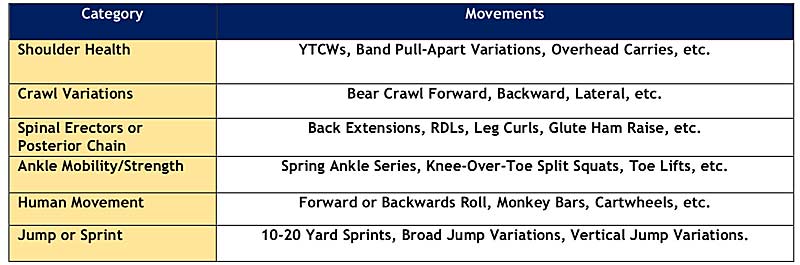

We combine prehab movements with total body movements in the warm-up to increase body awareness, muscular coordination, and human performance while improving resiliency, says @coachrgarner. Share on XAs shown in figure 6 below, we have six categories of movements to choose from:

- Shoulder health.

- Crawls.

- Posterior chain.

- Ankle mobility/strength.

- Human movement.

- Jumping/sprinting.

By assigning categories to our warm-up circuit, it ensures we train the areas needed to lower injury rates and raise athletic performance. The added benefit of categorizing our warm-up is if we’d like to give autonomy to our athletes, we can give them a list of movements to choose from in each category, and they can decide what works for them.

Each day, we should pick one movement from each category and perform 2-3 rounds. At the end of each round, athletes perform a short sprint or whichever jump is being measured that day. We use this to measure progress, evaluate readiness, and improve coordination and power outputs in specific positions.

High-Intensity Dryland Days

High-intensity dryland days focus on developing strength, power, speed, and total-body coordination. This is done through resistance exercises, jumps, and sprints performed in circuit fashion. Although it is a circuit, that does not mean we let our swimmers go through as fast as possible. Instead, we use a steady pace and recover as needed between movements. The added benefit to not rushing through the circuit is that we’re inducing an aerobic stimulus as a side effect, thus improving our aerobic base even when it’s not the focus.

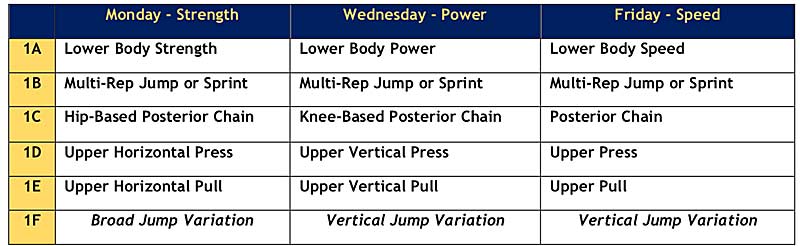

Each workout, athletes have six stations:

- Lower body main.

- Multi-rep jump or sprint.

- Posterior chain.

- Upper press.

- Upper pull.

- Measured jump.

Ideally, athletes perform the movements in this order, but logistics can play a factor. In my situation, I told the athletes to perform the main lower body movement and multi-rep jump or sprint back-to-back, and the measured jump last. The key is to perform the jump last because this ultimately serves as our program’s evaluation. Are we improving what we say we’re improving?

Figure 7 gives an example of a weekly layout for in-season training (working slow to fast with a single focus each day). How we categorize specific movements, such as squats versus deadlifts, determines where movements land in our training week. For example, I categorize squats as my lower body strength exercise and deadlifts as lower body power or speed, considering the movement and loading parameters. This means we squat on Monday and deadlift on Wednesday.

As a note, we use heavy deadlifts, which may be considered strength, but I believe they have a higher correlation to promoting max velocity, which is why they are placed in the middle of the week. The idea is that we are priming or potentiating the nervous system to be heightened for weekend meets.

Low-Intensity Dryland Days

The goal of low-intensity days is to build up our aerobic base and drive recovery. By improving our aerobic base, we increase the amount of work our swimmers can handle while improving the efficiency of our cardiovascular system. This is accomplished through continuous aerobic circuits or interval training.

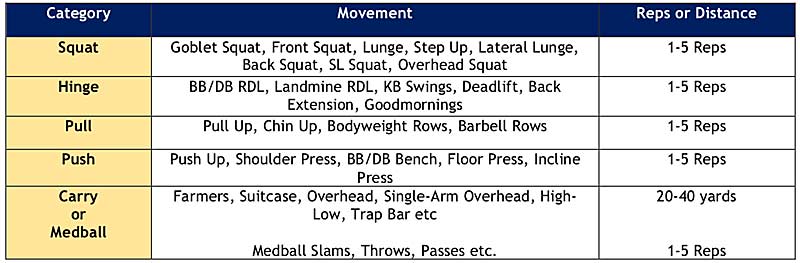

For continuous circuits, we place 20-30 minutes on the clock and get through as many rounds as possible. As the coach, you pick the movement and number of reps from five categories:

- Squat.

- Hinge.

- Pull.

- Push.

- Carry or medball.

Following the table below, we can create unique circuits week-to-week or let our athletes choose any movement they want within each category.

Performance over Endurance

As swim coaches, we must acknowledge there are more buckets to fill than just endurance, says @coachrgarner. Share on XDryland training adds another layer of stimulus to our training model in and out of the pool. As coaches, we must acknowledge there are more buckets to fill than just endurance. To build faster swimmers, we must have them swim as fast as possible in the pool and elevate their central nervous system out of the pool. By creating an environment where speed, power, strength, and overall human performance are pursued, we will develop well-rounded swimmers who are better prepared for today’s training and tomorrow’s races.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF