Swimming is a sport known for high yardage, two-a-day practices, and long hours in the pool. The grind of swimming is a source of pride, and if you’ve ever swum laps, you can appreciate the sport’s incredible difficulty. Holding your breath and exerting max effort is hard enough but doing both at the same time is a whole different ballgame.

For most swim coaches, the key to success is yardage and time in the pool, which has inspired coaches to use long yardage at submaximal efforts to train and develop swimmers. But when it comes to how the body adapts, this may not be the best approach for improving swim speed. Short distance swimmers are sprinters, and they need to swim as fast as possible for as long as possible. Fortunately, there are new approaches to make this happen.

What Is the High-Low Training Model?

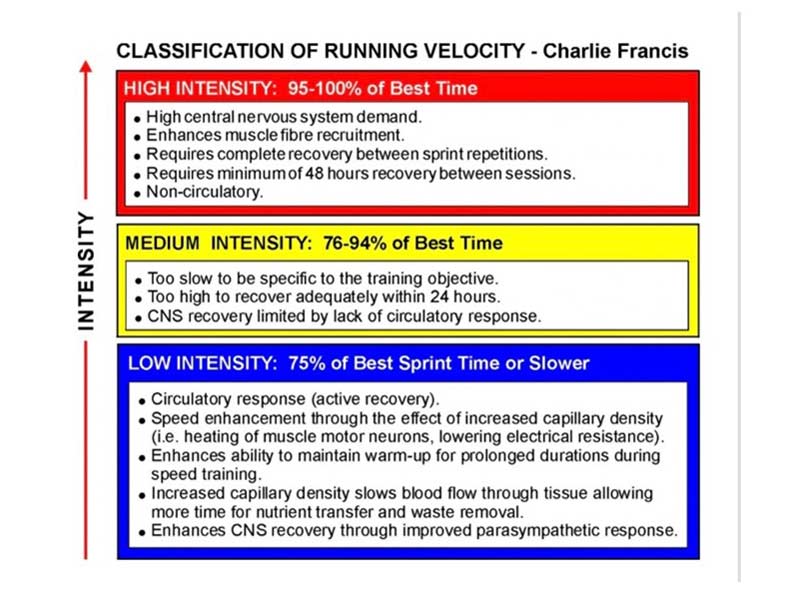

Charlie Francis created “The High-Low Training Model” to develop world-class sprinters. This model divides training into high-intensity and low-intensity days while avoiding medium-intensity days. The goal of this model is to maximize speed and power adaptations on high days while increasing work capacity and recovery adaptations on low days.

High-intensity days are anything greater than 95% of your best time, middle-intensity days are between 76% and 94%, and low-intensity days are less than 75% (as shown in the chart above). Personally, I believe we can use efforts over 90% for our high-intensity days because younger athletes will struggle with producing consistent efforts over 95%.

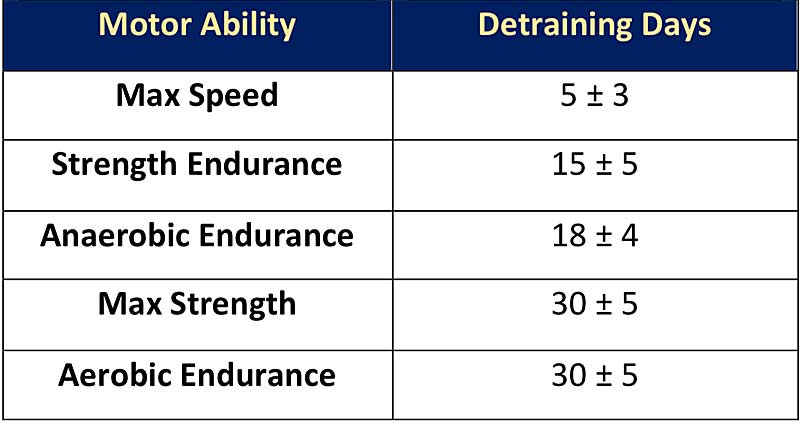

I believe we can use efforts over 90% for our high-intensity days because younger athletes will struggle with producing consistent efforts over 95%, says @coachrgarner. Share on XIf you’ve worked with athletes before, you know that speed and power can be hard to develop and that improving them requires allocating a significant amount of time. Speed must be trained constantly because it will start to detrain within 5 ± 3 days (See figure 2). This means we need to train speed at least twice a week to improve this quality. With this model, we will have three high and three low days during the week, with the seventh day being a rest day.

The key to running a high-low model is to make sure our highs are high, and our lows are low. When I talk about this model with coaches and watch them implement it, their highs are often not high enough, while their lows are not low enough. Instead, something closer to the middle ground occurs (76%-94% of a best time or measurement), which defeats the purpose of this model. We end up creating an environment where athletes accumulate stress that is too stressful to recover from within 24 hours, therefore inducing minimal improvements in performance.

When stressing the body, we want to send a clear message to the brain. On high-intensity days, we want the body to be fast and powerful. On low-intensity days, we want the body to recover and improve capacity. By doing this, the body can optimally adapt to the stress we place on it. If we work in the middle-intensity zone though, the body does not know if we want it to be fast, slow, or powerful.

When stressing the body, we want to send a clear message to the brain…If we work in the middle-intensity zone, the body doesn’t know if we want it to be fast, slow, or powerful, says @coachrgarner. Share on XIn addition, all athletes have a certain bandwidth in terms of their ability to handle this middle-intensity zone. Some handle it better than others, and this zone is not nearly as trainable as the high and low zones. As a result, adaptations from the middle-intensity zone are minimal, which wastes time. We want maximal adaptation to the stresses we place on athletes, and they want the same.

Swimming and Track Are Brothers in Sport

Swimming and track share a multitude of similarities. Both sports feature short- to long-distance events, and everything is timed. If swimming and track coaches wrote down how they prepared their athletes, the lists would be hard to tell apart. Coaches use a variety of technique drills and distances to improve technical ability, speed, and capacity. Athletes perform specific drills to improve skill transfer—think pull-ups for swimming or bounding for sprinting—and the list of comparisons goes on. If asked what their main goal of training is, I am willing to bet most coaches in both sports wouldn’t hesitate to say: “Improving speed.”

Track coaches typically fall into two philosophies: high-volume-based or high-intensity-based. High-volume coaches believe that running for longer distances will help their athletes run faster and win races. High-intensity coaches believe sprinting or running at high intensity for shorter distances will improve speed. More often than not, swim coaches fall into the category of high volume: they believe that if their swimmers can handle more yardage, their swimmers will be faster.

This leads to a critical question that I ask myself all the time: Are my athletes successful because of what I’m doing or in spite of what I’m doing?

Autoregulation: The Key to Consistent Adaptations over Time

Before getting into the details of high- and low-intensity days, we first need to understand autoregulation, which I first learned about from Dietrich Buchenholz’s (DB Hammer) The Best Sports Training Book Ever! and Cal Dietz’s Triphasic Training. Autoregulation means that we base training on how we feel each day. This could be based off perceived effort, time, or outputs such as jumps or bar speed. This works perfectly with swimming because it is a stopwatch-based sport. Everything is measured, which means we know exactly how an athlete is feeling.

Autoregulation works perfectly for swimming because it is a stopwatch-based sport. Everything is measured, which means we know exactly how an athlete is feeling, says @coachrgarner. Share on XCoaches across the country disagree on the amount of volume swimmers need on a given day or week to cause positive adaptations. By autoregulating training, our swimmer’s daily performance determines the amount of volume they do day-to-day. This means our athletes get the exact amount of volume they need, as well as what they can handle, to push the adaptations we’re looking for.

Remember, the goal for our training is to make them faster in the future, not to make them tired just to be tired. Speed work can only be done when our swimmers are fresh and recovered from prior workouts. If we use too much volume at the beginning of the week, we will leave performance improvements on the table for later in the week. Worse yet, we will weaken their performance on race day.

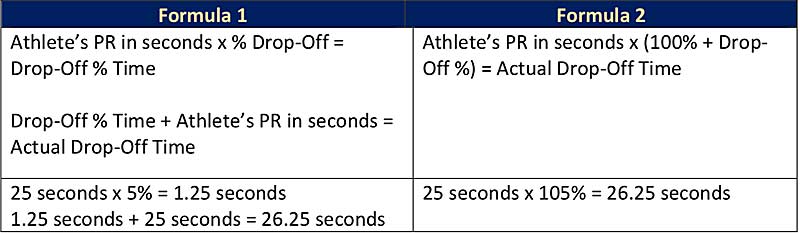

How does autoregulation work? On each day, the coach determines the percent drop-off for the day. What does percent drop-off mean? This refers to how much our athletes can “drop off” or slow down before they are done training for the day. Normally, we want around a 5%-10% performance drop-off per training day. This equates to 90%-95% of their best time.

We may find that some athletes can handle larger drop-offs than others and be able to recover within 48 hours. For example, swimmer A can handle a 3% drop-off, while swimmer B can handle an 8% drop-off. Due to logistics, we may not be able to individualize our training, which is understandable, but we should still make some mental notes on how well our athletes handle specific drop-offs.

When we begin using autoregulation, it’s wise to start out using a 5% drop-off and see how our team responds. As previously stated, we may need to lower the percent drop-off depending on our team and training schedule. The more we practice, the lower the drop-off. The less we practice, the higher the drop-off.

Weekly Practice Layout

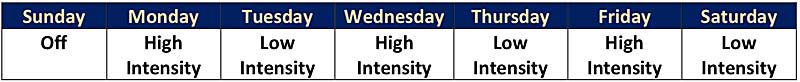

The weekly practice layout will alternate between high and low days. As strength and conditioning coaches, we should also align our high and low days with the practice plan. This puts a greater emphasis on each day but also sends a clear signal to the body that today is a high- or low-intensity day. Remember, we want the highs to be high and the lows to be low. On our high days, we should work on strength, power, or speed qualities. On low days, we should pursue aerobic or recovery-style training.

Below is an example of a six-day training week following the high-low model.

High-Intensity Days: The Details

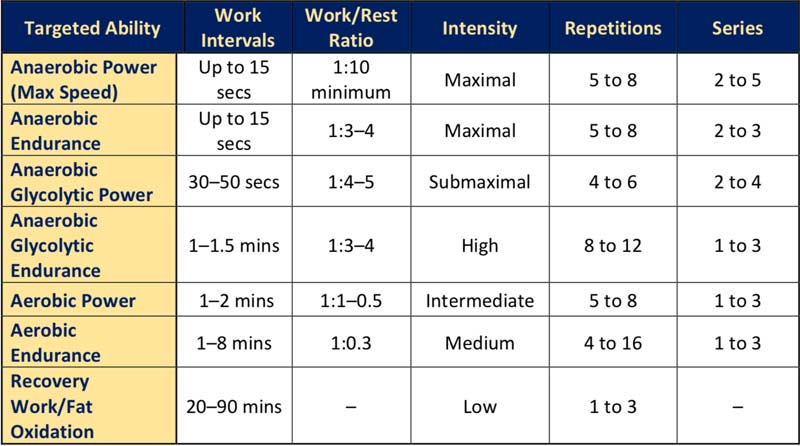

The key to high-intensity days is performing sets that are greater than 90% of our best time with complete rest in between. As stated previously, I think 90% is useful for most athletes out there. If we want a higher-quality day, then we may want to use 95% instead. This all depends on our athletes, our situation, and what our goals are. See figure 4 for proper work-to-rest ratios based on our work interval.

What does 90% of a best time look like? If our athlete hits a PR for the day at 25 seconds, then they cannot swim times slower than 27.77 seconds. If we used 95%, then times would need to be under 26.23 seconds. However, if the swimmer sets a new PR later in the workout, then we now use that number as our drop-off. For example, if they swam 25 seconds on their second set and then 24.5 seconds on their fourth set, we would use 24.5 seconds as our new PR for the fifth set.

This can also be applied to a jump height or sprint time in a workout. If we are looking to individualize our swimming program, then each athlete would perform as many repetitions as they can until they miss their required time or until practice time expired. This means some athletes swim three reps while others hit eight.

As previously stated, we may not want to individualize it this much—if not, we can begin tracking our swimmer’s times to see where most of the team drops off. Once we find this number, we can simply assign a fixed number of sets for the day and proceed. For example, if we performed eight sets of 50-meter sprints and found that most of our team dropped below 90% of their PR time on the fifth set, for our next practice we could assign five sets and call it a day.

As a side note, in the weight room I regularly have athletes set PRs on their last set of jumps or sprints (we do 5–6 total sets each day). If I can, I like to have my athletes leave on a PR or close to it because it builds buy-in to the program.

The tricky part of these days is that our swimmers may not “feel” like these are hard days because they are not gasping for air or their muscles are not straining with each stroke. Most come from a background of high yardage, and that is all they know. Remember, high intensity is referring to nervous system stress, which is often a hard concept for athletes to grasp (think central versus peripheral fatigue). Make sure you take the time to explain the differences between high- and low-intensity training because this will help with buy-in.

High-Intensity Days: Time Brackets

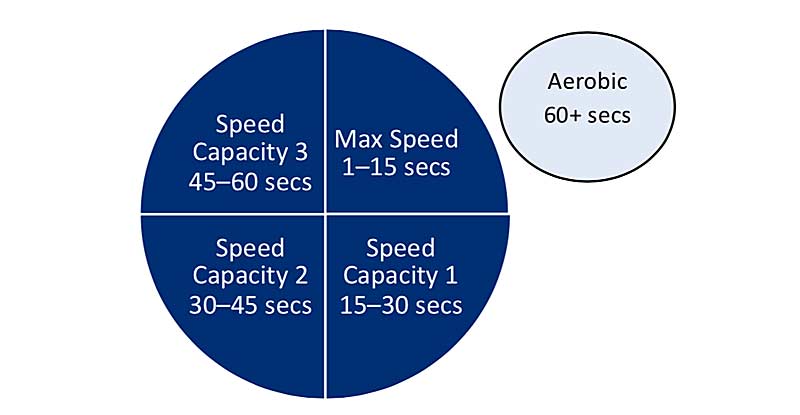

I first read about time brackets from The Best Sports Training Book Ever! and Triphasic Training as well. These brackets refer to specific time zones where one of the three energy systems is predominately active. The body’s energy systems operate based on how long you are straining during a set.

The alactic system is used when training for 15 seconds or less. The glycolytic system works between 15 and 60 seconds. The aerobic system is trained when straining for 60 seconds or more. In other words, peak speed, power, and strength are trained under 15 seconds. The capacity to handle more speed, power, and strength is trained between 15 and 60 seconds. Your ability to recover and breath more efficiently improves when training more than 60 seconds.

Time brackets are a great way to organize training and provide variation day to day. Figure 6 is a chart that shows an example of 15-second time brackets that could be used for swimming. I use 15-second brackets because they are easy to manage and apply working constraints to.

The key to high-intensity days is making sure our athletes are completely recovered between sets. As shown in figure 4, our athletes need a 1:10 work-to-rest ratio to be ready for max speed work. This means if they swim for 10 seconds, they need 100 seconds of rest to recover. Now, I believe resting around 60–90 seconds works fine, but the point is we need to give them ample time to recover. Otherwise, we begin entering the middle zone and building up lactate, which is what we are avoiding on speed days. I am not saying we can never go there, but for high-intensity speed days, we don’t want to live there.

When we use distances instead of time, we play a guessing game in terms of energy system development. Although we may not realize it, that is what we are doing when we assign distances: we assume “x” distance will train capacity or aerobic while “y” distance will train speed. By timing sets though, we know exactly what energy system is being stressed.

When we use distances instead of time, we play a guessing game in terms of energy system development, says @coachrgarner. Share on XLow-Intensity Days: The Details

The goal of low-intensity days is to develop aerobic capacity, improve cardiovascular health, and enhance recovery. These days create a circulatory response within the body, which promotes blood flow and enhances the transfer of nutrients and waste products in the muscle, promoting and optimizing recovery. In addition, by improving cardiovascular health, we lower our resting heart rate. Why does this matter? When we lower our resting heart rate, our heart pumps more blood with each beat. This means our body can work less to accomplish more, creating a more efficient cardiovascular system. In swimming, this is vital.

On these days, we do not need new PRs but can instead reference the athlete’s PR for the week or year. If our swimmer’s PR is 25 seconds, then they must swim 33.33 seconds or slower for low-intensity days. We can also put a time on the clock and have them swim for 20+ minutes at a <75% pace. Within the weight room, this is where circuit training is useful: for example, I like using 20-minute one- to five-rep aerobic circuits.

The focus these days should be on pace and technique or, as many coaches like to say, “feel for the water.” When our swimmers execute these sessions, they should not be gasping for air. Yes, they will be breathing more than on high-intensity days, and their heart rates will be consistently higher, but these sessions should not be something our swimmers dread. The key is to make sure their heart rates do not shoot too high: our goal is 120–150 beats per minute.

Low-intensity days are also great opportunities to incorporate some dryland work. Practices can get monotonous, but dryland work can freshen things up and bring a new stimulus to the table. For example, we can have our swimmers perform 50-meter laps with whatever stroke they like, then get out of the water to perform five pull-ups, five lunges, and five medball slams. Repeat for 20 minutes and get in as many rounds as possible.

We can use whatever we want for dryland: the point is to stimulate our athletes. Remember, it’s all about the heart rate and time bracket. Within those constraints, we can do what we like.

Low-Intensity Days: Time Brackets

The time brackets for low-intensity days are typically greater than 60 seconds, but we can also do submaximal aerobic work for less than 60 seconds. As shown in the previous example, we can assign a 75% pace based on a PR of 25 seconds, because this is considered low-intensity work. As long as the effort is <75% intensity, we can go as short or long as we would like. Again, the key is to get the heart rate between 120 and 150 beats per minute.

Putting It All Together

Here’s an example of what our week can look like. As the coach, we need to decide the swimming events, drills, and variations we perform. We can use boards, paddles, fins, power towers, or whatever we can imagine to generate the adaptations we want.

- Monday – High

-

- Time Bracket = 15–30 seconds.

- Physical Goal = power capacity.

- Distance/Stroke = depends on swimmer and average time of event.

- 5% Drop-Off.

- Dryland = strength, power, or speed development.

- Tuesday – Low

- Time Bracket = 60+ seconds.

- Physical Goal = aerobic capacity.

- Workout = 75-second swim, rest until heart rate is below 120 bpm. Repeat for rounds.

- Intensity = 70%

- Dryland = aerobic circuit.

- Wednesday – High

- Time Bracket = 1–15 seconds.

- Physical Goal = max speed.

- Distance/Stroke = 25–50 meters and whatever stroke you want.

- 5% Drop-Off.

- Dryland = strength, power, or speed development.

- Thursday – Low

- Time Bracket = 45 minutes straight.

- Physical Goal = aerobic capacity/fat oxidation.

- Workout = 50-meter swim, 5 pull-ups, 5 lunges, 5 medball slams for rounds.

- Intensity = 65%.

- Dryland = aerobic circuit.

- Friday – High

- Time Bracket = 30–45 seconds.

- Physical Goal = speed capacity.

- Distance/Stroke = depends on swimmer and average time of event.

- 10% Drop Off.

- Dryland = strength, power, or speed development.

- Saturday – Low

- Time Bracket = 30 minutes straight.

- Physical Goal = aerobic capacity/recovery.

- Workout = 5-minute swim, 2.5-minute dryland x 4 rounds.

- Intensity = 60%.

- Sunday – Rest

This model is designed for short-distance swimmers to develop speed in the water and create a robust aerobic energy system. Every week we chase PRs, all while ensuring our athletes get the proper stimulus. If the swim coach and strength and conditioning coach are on the same page, this model sets teams up for elite and long-term success.

Author’s Note: I am a sports performance coach with experience training swimmers. I am not a swim coach, but I have developed a framework for coaches to apply the best way they see fit. This model has been implemented by Heath Grishaw and me at Liberty University. Coach Grishaw developed the daily swimming drills, while I implemented the dryland training. Please feel free to contact Coach Grishaw or me if you’re interested in learning more.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Ross, great write up. If only we can get swim coaches to understand this. I notice no two-a-day model always questioned this for non-Olympic/ pro level swimmers. Other than a cultural, passed down way of doing business I’ve never been provided a good reason for the in season two-a-days other than the guess that it amplifies the effect of the Taper period. Would love to talk more!

Great Stuff!